At Orange County colleges, Cal State Fullerton isn't the only one

advertisement

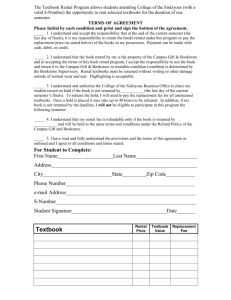

At Orange County colleges, Cal State Fullerton isn't the only one dealing with faculty-written textbooks By Lily Leung and Teri Sforza – Staff Writers November 9, 2015 It’s been long understood at Fullerton College that faculty cannot make a single cent off any self-created, custom course materials, from books to course packs. However, roughly two miles away at Cal State Fullerton, no such policy exists to keep faculty from doing just that. Schools across Orange County vary in how they handle faculty authored educational materials -- a touchy topic that exploded in recent weeks into a nationwide debate about academic freedom and soaring textbook costs. In the region, at least 500 higher-education classes during the most recent school session are taught by faculty members who require students to use their published works, according to a Register analysis of public documents. Sales of faculty-written materials at these schools could amount to hundreds of thousands of dollars for a single semester or quarter, assuming new copies are purchased in each case, based on the Register’s sampling of schools. The priciest such text at Chapman in the most recent semester was law professor Michael B. Lang’s “Federal Tax Accounting,” which comes with a $206 price tag at the campus bookstore. It can be purchased on Amazon in used condition for about $100. At Cal State Long Beach, a new copy of “Language Learning Disabilities in School-Age Children and Adolescents: Some Principles and Applications,” co-written by professor Geraldine P. Wallach, sells for $197 at the campus bookstore. Online, the book can be rented for as low as $17. “I think you bring upon yourself greater scrutiny when the book is not only expensive, but also happens to be written by a campus faculty member who benefits from its use,” said Meredith Turner, assistant executive director of the California State Student Association. At least two schools in the county have rules in place to address the topic of facultyauthored course materials. Nationwide, some institutions, such as University of Missouri and Iowa State University, require academic authors to give any royalties back to the school, or to charity. Cal State Fullerton has no such policy. Last week, the president of the roughly 39,000student campus stood by the school’s decision to reprimand associate math professor Alain Bourget, who assigned less expensive alternative textbooks instead of a text co-written by the math department chair and vice chair. Many faculty authors say they assign their books because they are experts in the field and are offering specialized knowledge. The profits argument is overblown, they contend, as typical royalties are meager and academic book advances are rare. The professors’ cut is often 10 percent to 18 percent, according to Stephen Gillen, a media and publishing attorney. In fact, faculty authors in a class-action case in New York court allege royalty payments have essentially remained flat over the years while textbook prices have ballooned by more than 80 percent in the last 10 years, according to the lawsuit. SCHOOLS WITH POLICIES At Fullerton College, faculty members are welcome to create education materials but not profit from them, said Nick Karvia, the school’s bookstore director. Karvia had to remind faculty about that rule last year, after the school discovered an instructor was selling a custom course pack to students at significantly more than what it cost to produce. That led to an audit that found other offending cases. “Those have ended,” Karvia said. The community college also requires prices of faculty-created class materials to be based on the actual cost to reproduce the material, which includes printing and binding. The bookstore does tack on a “standard” 23 percent, which goes toward the covering the bookstore’s costs, Karvia said. Students in at least 170 course sections were assigned texts published and taught by the the same professor, according the college’s campus bookstore list. Many of them are course packs or course notes. At CSULB, it’s considered a conflict of interest if a faculty member accepts royalties on assigned course materials, for personal use, says a 1999 policy. Exceptions include “materials published for a wider market, where the level of royalties is set by the terms of a publishing contract and likely to be nominal.” Faculty members cannot make royalties from preparing or editing course packs. There are roughly 80 courses that use books written by the instructor, according to the school’s campus bookstore list. SCHOOLS WITHOUT POLICIES At UC Irvine, the decision to use which course materials is left up to the faculty. “Given our research productivity and the academic freedom that is a core principle of the university, we trust our faculty to select the texts for their classes,” said university spokeswoman Cathy Lawhon. More than two dozen faculty members at UCI asked their students to buy books they had written for courses during one quarter last year, according to university documents. Together, those professors had enrollment of about 2,000 students. If every student bought the newest paperback edition, those transactions were worth about $122,000 to the publishers. Course material decisions at CSUF are made at the department level. There, students in about 150 classes were assigned faculty-written textbooks in the fall semester. Of those professor-author matches, there are 60-plus unique faculty authors, and some of the titles are note packets and course readers, said Paula Selleck, a university spokeswoman. The costliest faculty-written text was “Introduction to Counseling: Voices from the Field”, co-written by CSUF professor Jeffrey Kottler. A new copy at the Titan Bookstore is $225. On Amazon, an electronic copy of the text be found for as low as $79. Kottler could not be reached for comment. “We support the freedom of faculty members to develop course materials that best leverage their expertise,” Selleck said. “At Cal State Fullerton, faculty members are encouraged to grow and develop as educators and scholars.” Cal State Fullerton, she says, has “shown real leadership” in keeping textbook costs down for their students. In 2005, the school launched its textbook rental program, which offers a less expensive option to purchasing new or even used books. Eight of the 15 Southern California institutions contacted by the Register provided lists of educational materials sold at the campus bookstore in the most recent semester or quarter, or a list of faculty-written works. The Register also found that at: • Santiago Canyon College this semester, there were 50 courses where at least two dozen instructors assigned their own books, or one written by another faculty member. At the campus bookstore’s new-book prices, that would equate to sales of about $140,000. • Santa Ana College, at least 23 professors assigned materials written by themselves or other faculty members for 46 classes this semester, from art and biology to history and English. New copies of those books would total nearly $78,000 at the campus bookstore. • Golden West College has a total of four faculty-written books that are sold to students as required texts. Two of them are microbiology manuals. The revenue from those texts goes into a departmental account to offset classroom expenses not covered by the operating budget, said Letitia Clark, spokeswoman for Coast Community College District, which includes Golden West College. • At Chapman University, students in about 30 courses this fall were required to purchase books that were written by the teaching faculty member, according to a list provided by the school. “Our classes at Chapman are so small (average 14 students to one professor) that probably very little profit would be made anyway,” said Chapman spokeswoman Mary Platt in an email. ‘CAN’T JUDGE A BOOK’ Asked for response, Judy Iannaccone, spokeswoman for Santiago Canyon and Santa Ana colleges, said: “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” Some books that bear faculty members’ names are actually custom compilations of the work of others, and not faculty-written works at all, she said. Example: The $144 book for Business 170 that bears instructor Bob Ash’s name is actually a collection of chapters from a text that sells for $270 on Amazon. Ash was trying to get his students the pieces they needed without having to buy the entire, expensive book, she said. “Our professors have been very concerned about costs, and have been seeking options to save students money by not buying hardbacks, using older editions and e-books, arranging for textbook rentals, and working with publishers to develop custom materials that can be sold to students at a lower cost, without infringing on any copyrights,” Iannaccone said. School officials say many instructors are considered experts in the field and know what works and what doesn’t, so it makes sense they’d want to use their own texts. Take Lang’s book at Chapman. The law professor says “Federal Tax Accounting”, which he co-wrote, targets a specific type of student, one pursuing a specialized tax-law degree offered at only a couple dozen institutions. “There’s basically no competition for my book,” said Lang. Wallach, author of the learning disabilities text at CSULB, didn’t respond to requests for comment. Michael Spinella, executive director of the Text and Academic Authors Association, acknowledges that U.S. textbook prices have risen. But he says people tend to forget the amount of work that goes into creating textbooks, including the author’s work and “the people behind the textbook.” “The cost of those things have only gone up,” Spinella said. $400 PER SEMESTER William Vassetizadeh, president of Saddleback College’s Associated Student Government, spent $400 this semester on textbooks -- and that’s considered low, he said. He recalls one professor requiring students to hand in assignments with worksheets from the textbook attached, essentially forcing students to buy books new. Many courses also have online supplements that require an access code that only comes with a new book – and that can only be used once. Some instructors are more understanding than others, said Kevin Sabo, president of the University of California Student Association, which advocates for textbook affordability. Some will allow students to purchase older editions, which tend to be cheaper. Other instructors opt to use course readers, a compilation of materials, which also tend to be more affordable. Students are “making decisions between food and purchasing textbooks,” said Sabo, a fourth-year student at UC Berkeley. “They’re prioritizing food and shelter. Textbooks tend to get written off.”