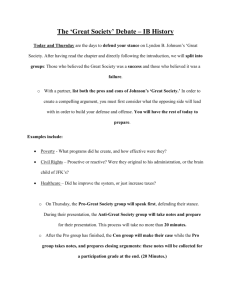

BC HS Debate Guide

advertisement

BC HIGH SCHOOL DEBATING GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Debating Calendar 2. Running Meetings 3. Games 4. Support Organizations 5. Style Guides i. British Parliamentary ii. Canadian National Debate Format iii. Cross Examination DEBATING CALENDAR For a complete list of the year’s tournaments, refer to the DSABC Website (see Support Organizations); included here are the major tournaments and styles to be practiced at certain times of the year. For details as to what each style entails, see Style Guides. UBC High School Tournament – BP/Cross X style: With skill levels ranging from beginners to the best in Western Canada, this tournament, which takes place from late October to early November, is the largest High School tournament in Western Canada. Law Foundation Cup – CNDF/Cross X style: This is BC’s provincial debating championship; to compete in the February tournament, you must do well in regional qualifiers, which usually take place in late January or early February. RUNNING MEETINGS To help your meetings run as smoothly as possible, we’ve included a couple of tips to make it easy for you. We’ve also included some games (below) which we’ve found fun. • Hold a debate every meeting! A game can be fun to break things up, but you should be holding a debate as often as possible. • Get everyone to debate, especially those new to the club; it is beneficial to everyone to have a large pool of competitive members to practice with. • Make sure you’re practicing the proper style; you will often find that you will enjoy one style more than another, but you won’t be competitive at tournaments if you’re unable to engage properly in the style specific to that tournament. • Go to as many tournaments as you can; its great experience for all members to meet new challenges, and you get to meet and engage with numerous like-minded, interesting people. • Find a coach; if your school has a long tradition of debate, you may be able to receive skilled judging from your senior students. However, for those new to debate, a UBC coach (if you need one, see below how to contact us) or otherwise can go a long way to providing the necessary experience. • Take it easy! Debate should be a fun and engaging way to exchange ideas, and unfortunately, some clubs lose sight of that in the drive to compete. Some competition is absolutely essential, but forgetting the big picture can lead to a stressful, unhealthy club atmosphere. GAMES There are a number of situations in which you might need a good game to liven up a meeting. While we encourage you to come up with your own games, (and share them with us!) here are a few that we’ve found fun and/or helpful. If you have any you’d like to add, send them our way, and we’ll be sure to include them on next year’s list. Icebreakers 1. Sombrero/Top Hat Debates • Start with a list of topics. They should be broad, interesting, and probably silly, though they can surround any topic you like. You should have 20 or so. • One debater, chosen at random, draws a topic from a Sombrero/Top Hat, and must give a 1 minute speech in support of topic. Creativity is encouraged. • The next debater gives a speech in opposition to the topic for 1 minute. • Repeat, with a new debater and new topic. • The goal of the game is to encourage new debaters to become comfortable with public speaking in a fun environment. 2. Triple Speech • 3 minute speeches • Participants pick a topic from a hat and speak for one minute about it. • Then, they pick a new topic and speak for the 2nd minute about that, then repeat for a 3rd topic and minute. • Must transition between topics • Aids public speaking, impromptu idea development Skill Development 1. Backwards Debate • Begins with the judge giving the RFD, and telling each of the debaters how their speeches went. • Debate begins in reverse speaker order, starting with the whip. The debaters use the criticism of the judge as areas to focus on doing well, and stick exclusively to the content the judges told them that they had provided. • They also rebut the statements of the next speech (already knowing the content the judge provides). 2. POI Round • Set up two teams; one person on the 1st, and 3-4 on the 2nd. • 1st team begins a speech in support of a resolution (little/no model); after 2-3 minutes, the 2nd team begins POIing. They take turns offering POI’s, and the speaker must take one every 30 seconds. • Round ends when speaker is stumped by a POI. • Goal is encourage creative, deadly POI’s and quick, coolheaded responses. 3. (Subject) only Round • Normal debate round, except only points concerning a certain subject may be considered, such as Econ or (tougher) Ethics/Morality. • Encourages the creative development of points, as well as a deeper understanding of the application of certain subjects. 4. “You must be joking” • Partners are given a high burden case, such as “Legalizing all Narcotics.” • One argues for each side, or it’s combined with a POI Round. • Goal is to develop arguments from First Principles. • Creative arguments are also encouraged. SUPPORT ORGANIZATIONS Debate and Speech Association of British Columbia (DSABC) http://www.bcdebate.org/ UBC Debate Society (UBCDS) http://ubcdebate.com/highschool/ ubcdebate.highschool@gmail.com STYLE GUIDES British Parliamentary (BP) Introduction: This guide is aimed primarily at those of you who have little to no British Parliamentary experience. It is intended to illustrate the mechanics and basic tactics of BP. Sometimes beginners can be discouraged by BP because of various factors in the round. But BP done well can be an incredibly rewarding experience, and trying BP can improve the way you debate in other styles. The Basics: In BP there are 4 teams in each round. Two teams represent the Government, and two teams represent the Opposition. The Government supports the resolution, and the Opposition opposes the resolution. The teams are also divided into the Opening and Closing halves of the debate. The teams are organized like this in the room: | Opening Government (OG) | Opening Opposition (OO) ______|______ | Closing Government (CG) | Closing Opposition (CO) | There are two speakers on each team. Each speaker has a title. The titles are: OG: Prime Minister Deputy Prime Minister CG: Member of the Government Government Whip OO: Leader of the Opposition Deputy Leader of the Opposition CO: Member of the Opposition Opposition Whip The speaking order is as follows: 1. Prime Minister First Speaker, OG 2. Leader of the Opposition First Speaker, OO 3. Deputy Prime Minister Second Speaker, OG 4. Deputy Leader of the Opposition Second Speaker, OO 5. Member of the Government First Speaker, CG 6. Member of the Opposition First Speaker, CO 7. Government Whip Second Speaker, CG 8. Opposition Whip Second Speaker, CO Debates are presided over by a Speaker, who is often the Chair of the adjudicator panel. The Speaker keeps time and calls debaters to the floor. Each debater has 7 minutes to speak. The first and last minutes are protected time. This means that no POIs may be offered during this time. The Speaker will give a signal at the end and the beginning of protected time, at the seven-minute mark, and at the end of grace. The Speaker will probably not give time signals otherwise, so it is recommended that debaters bring a stopwatch to time themselves or their partner. There are no Points of Order, or Points of Personal Privilege. At the end of each debate, the teams will be ranked from first place to fourth place. Each ranking has a point value associated with it. The common point values used are as follows: First Place = 3 points Second Place = 2 points Third Place = 1 point Fourth Place = 0 points Your points are added over the course of the tournament. The break is determined by point total, and speaker points if some teams have the same point total. Matter and Manner In BP there are two categories that you are judged on as a speaker. Matter is the content of your speech, and manner is how you present that content. Matter and manner are weighted equally. The lists include some of the more common elements of matter and manner, but are not exhaustive. Matter Includes: • Substantive arguments for your side • Rebuttal arguments • Case Studies / Facts • POIs Manner Includes: • Humor • Appropriate language • Engaging the audience Roles of the Teams and Speakers You’ll hear a lot about the “roles” of teams and speakers in BP. In order for a round to be able to develop properly, the teams participating in the round must fulfill certain criteria. When they succeed they will have fulfilled their role and they will be developing the debate. If they fail then the debate will suffer in quality because of it, and this will absolutely be considered in the adjudication. Roles of the Teams (Overview) Opening Government: • Defines the terms of the debate • Opens the case for the Government • Opposes the case of the Opening Opposition when it is presented Opening Opposition: • Opposes the case of the Opening Government • Opens the case for the Opposition Closing Government: • Extends the Government case • Opposes the cases of the Opening and Closing Opposition teams • Summarizes the debate Closing Opposition: • Extends the Opposition case • Opposes the cases of the Opening and Closing Opposition teams • Summarizes the debate Roles of the Speakers (Overview) Prime Minister (Opening Government): • Defines the resolution • Introduces the Government case Leader of the Opposition (Opening Opposition): • Rebuts what PM said • Introduces Opening Opposition case • If there’s going to be a definitional challenge, the LO must mention it in their speech, otherwise all the other teams in the round must accept the original definition (See: Challenging the Definition) Deputy Prime Minister (Opening Government): • Rebuts what LO said • Continues Opening Government case Deputy Leader of the Opposition (Opening Opposition): • Rebuts what DPM said • Continues Opening Opposition case Member of the Government (Closing Government): • Extends the Government case • Rebuts what DLO said Member of the Opposition (Closing Opposition): • Extends the Opposition case • Rebuts what MG said Government Whip (Closing Government): • May introduce new contentions, but it’s not generally recommended • Rebuts what the MO said • Summarizes the debate Opposition Whip (Closing Government): • Absolutely no new contentions may be introduced, but new evidence in support of existing contentions may be introduced • Rebuts what the GW said • Summarizes the debate Role of the Opening Government The first goal of an OG team is to present a clear, coherent, and above all, contentious case. Remember that the OG case must be contentious enough to last for eight speeches, and 56 minutes of debate. One of the most important things OG teams should keep in mind is that bold cases are generally better to run than squirreled cases that run out of steam within the first few speeches. It is debate, after all. This doesn’t mean that you should propose that humans eat their young. But it does mean that you shouldn’t be afraid of proposing controversial models or cases. The major point: Propose bold, but not suicidal cases. The next thing that you must remember as OG is that your case must be within the spirit of the resolution. At most BP tournaments the resolutions are directed. This means that the resolution will hint at the topic that should be discussed. However, the wording will usually be such that the OG will have a degree of flexibility in how they frame their case. However, a degree of flexibility does not mean that the OG can ignore the resolution (like we do at most CUSID tournaments). An example of an acceptable and unacceptable interpretation of a resolution: Resolution: THW Sell its Children Acceptable: THW Legalize Surrogacy for Profit Unacceptable: THBT Developing Nations Should Prioritize Economic Development over Environmental Protection The reason why the second interpretation is abusive is because the original resolution clearly hints at a topic involving the exchange of children for some benefit. This could be a myriad of things, from surrogacy for profit, to foreign adoption limits. So the OG has a degree of flexibility in choosing a topic relating to the selling of children. With this in mind, the second interpretation clearly goes against the spirit of the resolution. The Role of the Opening Opposition The Opening Opposition role is probably the one that debaters new to BP will have the least amount of trouble with. It’s fairly similar to the standard CP Opposition, but with different timings. However, there are some extremely important differences between the two. As the OO team, your role is twofold. You must refute what the OG team has said, but it is not enough to simply poke holes in the OG case. You must also bring in constructive arguments of your own. It is not enough to go into a BP round as an OO team and do a rebuttal-only opposition. A good OO case would make sense if the wording of the resolution were reversed, and OO became the OG. You have to bring your own constructive analysis to the round. Good OO teams will often tie in some of their rebuttal with their constructive points as well. This allows the judges to see that you’re engaging with the other team’s arguments as well as using them to build up your own. Using this style will also help you stay under the time limit, which is often a difficult thing to do if you’re faced with a lot of rebutting and summarizing. So remember: It’s not enough to say why their ideas are stupid, you have to say why your ideas are smart. The Role of the Closing Teams The closing positions of the debate are where we see the most significant difference between BP and CP debating. Both closing teams are expected to offer an extension for their opening team’s case. What is an extension? An extension can take many forms: • Switching the focus of the debate from practical to philosophical arguments, or vice versa • Bringing in new practical/philosophical arguments • Focusing on a specific case study • Focusing on an already mentioned argument and expanding on it significantly This is an incredibly short list of acceptable extensions. The main goal for a closing team is to differentiate yourself from the opening team, but still support them. It is very important that you support the opening team. But at the same time it’s still important for your arguments to be better than theirs. So you have to make sure that your case has an over-arching theme that the judges can easily identify, that makes your team distinct from the opening team, and still supports the opening team. This doesn't have to be difficult. Many teams stress themselves out about the closing positions because of the extension, but being on the closing half of the debate has distinct advantages. The closing teams have the ability not only to introduce their own constructive matter and rebut what the other team has said, but also to summarize the debate in their own words. The summary is to be done by the second speaker on each closing team. This is an integral part of the role of each closing team. There are many ways to summarize the debate. Some speakers like to identify the main themes that were analyzed during the round. Some speakers like to label each team with a name describing their arguments. One of the easiest ways for debaters new to BP to go through their summary speech is to identify three questions that need to be answered at the end of the round, and say why your side, and particularly your team, bring the best resolution to those questions. Any style you choose is fine so long as it gives a substantive summary of the arguments in the round, and why you won those arguments. As a reminder: The Opposition Whip is not allowed any new arguments in their speech, and it is highly recommended that the Government Whip focus entirely on summery, as well. Basic Tactics and Pitfalls: POIs: • Give two POIs, and take two POIs • POIs shouldn't be given for the sole purpose of destroying the other team's case. POIs should build your case up as well. • If you're in the opening half of the debate your priority in the second half should be to remain involved. Make sure your arguments aren't lost among the second half of the debate. POIs are the best way to accomplish this. • If you're in the second half of the debate then you should be extremely careful about the POIs that you give to first half teams. Sometimes your opening team may try and steal your extension if you give too much away in your POIs. • Try to remain involved in the debate by standing on POIs, but do not harass the speaker by continually standing on POIs and saying things like "On Liberty", "On the Geneva Convention", etc. • It is always better to get in one or two excellent POIs than four or five mediocre ones. One of the best ways to accomplish this is for you and your partner to put a sheet a paper between you with your best POI written down. Then, when the speaker takes either of you you're certain to have an excellent POI. • Just because everyone else is standing up on a POI doesn't mean you have to, Sometimes when a speaker says something monumentally stupid everyone on opposite benches will stand up. Usually the speaker won't take a POI at that time, but if there's someone who stood up late, they just might let them ask a question. Often, the debater giving the POI will be caught off-guard by this. So don't stand up on a POI just because everyone else is. But if you do, make sure you have a question. • Let people finish their question before you wave them down, but if they start to make a speech, or refuse to sit down, start waving them down immediately. If they still won't sit down then the speaker will deal with them. • Finish your thought before you accept a question. It is very easy to forget where you were if you allow someone to interrupt you. • If you want to get your question taken it is often better to stand at the end of the speaker's point. They'll be more likely to take you. • If you are in a round with teams of very disparate skills, it may at first seem like a good idea to take POIs from the weakest team. And that can work. But the judges will be more impressed if you give a good answer to a difficult POI than if you smack down a weak POI. So you might want to choose to take POIs from the better team. This will show the judges that you're willing to engage the better team in the round. Organization: • At the beginning of your speech tell the judges what you're going to be speaking about. • More advanced debaters may feel comfortable speaking without numbering their points or signposting where they're going with their speech. But the majority of beginning BP debaters will probably find it helpful to number their points and to make very clear to the judges what they're speaking about. This helps the judges keep track of your most important points, and it helps you cover everything you need to. • Pay attention to your timing. If you say that you're going to introduce three constructive points and then you run out of time, that will reflect poorly on you. • Always fill your time. Speaking Style: • The most important thing is to keep the audience engaged. You don't want them drifting off and thinking you're boring. • There are many ways to keep the audience and judges engaged. These include humor, intelligent analysis, and delivery. • Not everyone can be a funny speaker, and that's ok. Most people aren't. But it will help if you can use a few funny quips, or open with a joke. • Avoid being monotonous. Vary your tone and pace of delivery. • Never insult another debater's race, gender, sexual orientation, or religion. Anything offensive will be penalized. Err on the side of caution. Analysis: • Try to introduce facts, case studies, and philosophical analysis instead of statistics. • Statistics are boring, they can be easily dismissed by the opposition, they generally fall into "specific knowledge", and they're easily falsified. • Focus on examples. Appropriate examples and case studies will make a case better for the beginning BP debater than any pretty rhetoric can. • Stay focused. Remember what you are trying to communicate to the audience, and then communicate it. Don't go off on tangents. Definitional Challenges: • Definitional challenges are exceedingly rare. • Do not object to a definition of a resolution if it is merely stupid or generally bad. • The only time you should object to the definition is if it is a truism or tautology. • The only speaker who can object to the OG definition is the LO. If the LO doesn't object, no one else can. • If the LO objects to the definition then they must substitute their own. • The remaining debaters then have to decide which definition to use. • If the remaining debaters use the LOs definition then the debate can continue on like normal. • If there is still disagreement about the definition then the closing teams must decide which definition to support, or whether to substitute their own. • This is why it is usually an exceptionally bad idea to challenge a definition that isn't a truism or tautology. It's very messy. Knifing: • Knifing is when a closing team, or even a partner on the same team, blatantly disagrees with a fundamental part of the substantive case that they're supposed to be supporting. (Effectively knifing someone in the back). • In the vast majority of situations you should not knife your opening team. It will be a negative factor for you in the adjudication as supporting your opening team is a fundamental part of your role. • However, occasionally your opening team will be so shrill and off the mark that you'll have to basically ignore what they said in order to salvage your side of the round. You may have to twist what they said in order to make sense of their case. Be careful with this strategy. You probably won't take a first, but you may be able to salvage a point or two out of the round. Tactics for High Bracket Rounds: • While it is always a good thing to take a first place in a BP round, once you get into the high bracket rounds the most important thing is to avoid taking the fourth.. • When you get into high rooms you'll find that the competition between the teams becomes that much closer. So it's important not to give the judges an excuse to drop you. Watch the small things as well as the big ones. Be careful with timings, signposting, and rebutting what your opponents have said. • Do not stress out about your position in the round, or whether other teams are really good. Concentrate only on staying involved in the round, and demonstrating good analysis and argumentation. A lack of confidence will show through. Canadian National Debate Format (CNDF) Style This is the new style of debate to be used at the National Debating Championships. Individual provinces are strongly encouraged, but not required, to implement this style at their qualifying events. It is in some ways a cross between Parliamentary Debating and World’s Style Debating. Teams Each team consists of two people, and the teams are called the “Proposition” and “Opposition”. Individual speakers are referred to as its First and Second Speakers. Topics Topics are to be on substantive issues. All motions will start with “This House ...” No squirreling is permitted. The speaking order: First Proposition Speaker - Constructive Speech 8 minutes First Opposition Speaker - Constructive Speech 8 minutes Second Proposition Speaker - Constructive Speech 8 minutes Second Opposition Speaker - Constructive Speech 8 minutes First Opposition Speaker - Summary/Rebuttal 4 minutes First Proposition Speaker - Summary/Rebuttal 4 minutes Description of Constructive Speeches (a) The first proposition speaker has to define the terms, establish the caseline and give the case division (who covers what points). This speaker will normally have two or three constructive arguments. The first speaker must make the team’s approach crystal clear. (b) The first opposition speaker must clash with the points just made by the first proposition and advance the caseline, case division and normally the first two arguments of the opposition side. In World’s Style, this division is usually 2 minutes and 6 minutes, although for our purposes these are just guidelines. The debater should be evaluated on the overall effectiveness of the speech. Constructive argumentation or refutation may be done first, and once again, the judges will consider the effectiveness of the strategy chosen. (c) The second proposition speaker has to clash with the case presented by the first opposition speaker, and should advance one or two more constructive arguments for the proposition. The speaker should also take time to rebuild the proposition case. The arguments must have been announced in the first proposition speech. (d) The second opposition speaker should also introduce one or two constructive arguments. These new arguments must have been announced in the first opposition speech. This speaker should also take time to clash with the new constructive matter presented by the second proposition, and summarize the opposition case presented. He/she should NOT engage in an overall summary / rebuttal of the debate. Summary / Rebuttal Speeches The first speaker on each side, starting with the Opposition, will deliver a four minute summary/rebuttal speech. It was decided that there would be no set format for this speech, given the variety of valid strategies and techniques used. In general, speakers should attempt to summarize the key themes or ideas that have taken place in the debate. This speech tries to put the debate in context and explain the ‘crux’, or the internal logic of both cases and explains why, on this basis, his/her team has to win. It can examine and summarize the arguments presented, but should focus on the major areas of contention that evolved during the round. This is the final opportunity for a team to convince the judge why his/her team has won the round. During those speeches no new constructive arguments may be introduced except by the proposition debater who is exercising his/her right to reply to new arguments tendered during the final Opposition constructive speech. he/she can not introduce new lines of reasoning. The counter argumentation and counter example (or even counter illustration) must be in 'close and direct' opposition to the opposition points. Points of Information Points of Information, also known as POIs for short, are used in Worlds Style, plus a variety of other debating forums. Essentially, a POI is a question or statement that one makes while someone is giving a speech as a means of gaining a tactical advantage. It is expected that every speaker offer and accept POIs during the round. POIs are only allowed during the constructive speeches, but not during the first and last minutes of these speeches ( called “protected time” ). During the round, the moderator will bang the desk after one minute has elapsed to signal that POIs are now allowed, and again with one minute remaining in a speech, to signal that time is once again protected. Points of information should be short and to the point. To offer a Point of Information, a debater may stand silently, possibly extending an arm. A debater may also simply say “on a point of information”, or “on that point”. The speaker has control over whether to accept the point. One may not continue with their point of information unless the floor is yielded by the speaker. The speaker may do one of several things: a) Reject the point briefly, perhaps by saying something like “no thank you” or “not at this time”. The debater who stood on the point will sit down. It is also acceptable for a debater to politely wave down the speaker without verbally rejecting it and disrupting his/her speech. b) Accept the point, allow the point of information to be asked, and then proceed to address the point. A speaker may address the point briefly and move on, choose to merge an answer into what they were going to say, or state that they will deal with this later on (in which case be sure you do!) c) Say something like “just a second”, or “when I finish this point”, and then yield the floor when they have finished their sentence or thought. It is expected that each debater will accept at least two POI’s during his/her remarks. Each debater on the opposing team should offer, at least, two POI's to the debater delivering the speech. Adjudicators are instructed to penalize teams if the lower limits are not attained! How well a debater handles themselves in the rough and tumble of offering and accepting POI’s is key in this style of debate. Evaluation The ballot for this style of debate contains the following criteria: Content, Style & Strategy. While points of information do not get marks on their own, they are weighted, perhaps significantly, in a judge’s decision. Judges are encouraged to score holistically and award a final score that makes sense in both absolute and relative terms. The win-loss is critical, and judges must weigh this very carefully in their adjudication. For more details, see the adjudicator guide. Other Points Points of clarification, order, points of personal privilege and heckling are all prohibited. Cross Examination Style (Cross X) Introduction Cross-examination debate has a flavour all its own. Debating of every type rewards those who can think on their feet, speak well and prepare thoroughly; but Cross-examination debate puts special emphasis on these qualities. Debaters must answer questions immediately - without destroying their own case or aiding their opponent’s. They must conceal their own damaging admissions behind a facade of indifference. And they must know their case sufficiently well that they can pull the most telling facts together to answer an unexpected query. In short, this style of debate highlights three vital characteristics possessed by a good debater. How it differs from other styles Cross-examination debating was developed in the 1920’s, probably in the Pacific northwest, to accentuate the clash in debating. It differs from Parliamentary debate in two senses: no formal interruptions (Points of Order or Privilege) or heckling are permitted; and there is a period at the end of each debater’s speech when he or she is questioned by an opponent. In a sense, then, Cross-examination debate is more a copy of the court room than of Parliament, but this comparison is misleading. The content or substance of each debate is introduced through a debater’s constructive remarks, and the cross-examination period is chiefly a way of identifying differences in the two cases rather than a means of introducing information. The fact that no interruptions are permitted allows a debater to have better control over the timing of his or her remarks - a telling point will not be interrupted at the climax by a Point of Privilege. But the crossexamination portion of the debate forces a debater to respond to opponent’s arguments, pins him or her down to particular views, and exposes his or her own argument to a fairly searching analysis. The rules of Cross-examination debate differ from other debate styles only slightly: 1. No formal interruptions are permitted during the course of the debate, although at the end of the debate, an opportunity will be afforded to debaters to complain of any rule violations and misrepresentations by their opponents. 2. At the end of each debater’s initial remarks (but not after the rebuttals, if separate rebuttals are permitted), he or she will be questioned by an opponent, usually for up to two or three minutes or so. 3. While being questioned, a “witness” may only answer questions; the only questions permitted in reply are to have a confusing query answered. Witnesses must answer the questions themselves – neither the witness nor the “examiner” may seek help from a colleague, although both may rely on source materials and books during the examination. The witness must answer all questions directly and honestly. 4. While asking questions, an examiner may not make statements or argue with the witness; he or she may only ask questions of the witness. Judges are instructed to disregard information introduced by an examiner while questioning, and to penalize examiners for breaking the rules. 5. There are no formal rules of evidence which govern the sort of question which may be asked, though common sense dictates that the examination should be limited to fair questions on relevant subjects; these need not arise out of the preceding speech. Moreover, there must be no brow-beating or attempts to belittle an opponent, and debaters must treat one another with courtesy. Many of the conventions of Parliamentary debate are also absent - there is no proscription which prohibits calling another debater by name, and it is common practice to address opponents by their first names, especially during the course of cross-examination. They may also be addressed as “witness” and “examiner”, as the case may be, but pejorative references should be avoided. Except when questioning or answering questions, one’s opponents should always be referred to in the third person rather than directly. (For example, “he told you that ...”, “the witness said ...” or “my friend thinks ...”, but not “you told us ...” or “you said.”) The moderator and any other members of the audience may be addressed either directly or generally and it is common to refer to “Ladies and Gentlemen”. “My point, ladies and gentlemen, is simply that ...” correspondingly, teams are not the “Government” and the “Opposition” but rather the “affirmative” and the “negative” (or occasionally the “proposers” and the “opposers”). Of course, individual members of a team may be referred to as noted above, but as there is no “House”, they are not “Honourable Members” but at best, “Honourable Friends”. The procedures that prevail at a cross-examination debate are much the same as those present in a Parliamentary House, with a chairman moderating and introducing each debater at the beginning of his remarks (but not introducing the debater conducting a cross-examination: that follows directly on the conclusion of a constructive speech, without interruption or further introduction). Speaking Times (two person teams) 1st Affirmative (constructive speech) 4 minutes Cross-examination by 1st Negative 2 minutes 1st Negative (constructive speech) 4 minutes Cross-examination by 2nd Affirmative 2 minutes 2nd Affirmative (constructive speech) 7 minutes Cross-examination by 2nd Negative 2 minutes 2nd Negative (constructive speech) 7 minutes Cross Examination by 1st Affirmative 2 minutes 1st Negative (rebuttal-defence-summary speech) 3 minutes 1st Affirmative (rebuttal-defence-summary speech) 3 minutes