OVERSIGHT AND ACCOUNTABILITY MODEL

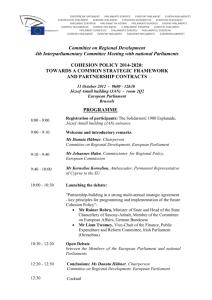

advertisement