New & Noteworthy

advertisement

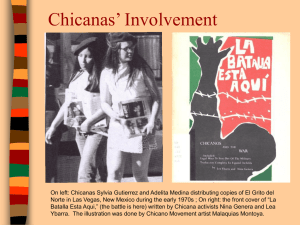

reviews New & Noteworthy The Chicano Movement of the 1960s and 1970s gained national prominence fighting discrimination against Mexican Americans, but women’s contribution to the cause is frequently downplayed. In ¡Chicana Power! Contested Histories of Feminism in the Chicano Movement, Chicano studies professor Maylei Blackwell shines light on Mexican American women’s fight for equality. For the book, ¡ chicana power! Blackwell drew on documents written by Chicana activists and oral histories contested gathered over the past 20 years to histories of feminism in the create the “first book-length study of chicano women in the Chicano movement.” movement The book focuses on Anna by Maylei Blackwell, NietoGomez, a Chicana theorist and University of Texas Press founder of Hijas de Cuauhtémoc, a 2011, 304 pp., $24.95 feminist newspaper and organiza(paperback) tion from Long Beach, California, that opposed male domination, racism, and classism. Blackwell notes that Chicana activists faced numerous hurdles to social equality, foremost among them the “chauvinism, discrimination, and sexual harassment” of male Chicano movement leaders. Tracing the role of women in the movement’s development, the book paints an illuminating picture of Chicano movement history from a feminist perspective. mythohistorical interventions­: the chicano movement and its legacies by Lee Bebout, University of Minnesota Press, 2011, 248 pp., $25 (paperback) ­What impact have stories and mythology had in the Chicano movement? Author Lee Bebout, a professor of Chicano studies at Arizona State University, explores “mythohistorical intervention” as a strategy that social movements use to foster dialogue, to unify, and to mobilize. He focuses in particular on the myth of Aztlán—the fabled land from Oregon to Texas from which the Aztecs migrated to establish their empire in presentday central Mexico. According to Bebout, the idea of Aztlán, as perpetuated in Chicano literature, formed “the narrative founda- 82 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS VOL. 45, NO. 2 First coined by feminist theorist and author Gloria Anzaldúa in 1987, the term spiritual mestizaje refers to “the transformative renewal of one’s relationship to the sacred,” according to Theresa Delgadillo, a literary specialist and author of this study of the concept’s significance in Chicana literature. In short, spiritual mestizaje is the alteration of one’s consciousness to resist oppression—wherever it may spiritual come from—to discover “alternative mestizaje: religion, gender, visions of spirituality.” The concept race, and nation of spiritual mestizaje originated in in contemporary the U.S.-Mexico borderlands, a rechicana gion of colonial and neocolonial colnarrative lisions between disparate cultures, by Theresa Delgadillo, religions, peoples, and more. Duke University Press Delgadillo’s book analyzes the 2011, 274 pp., $23.95 impact of spiritual mestizaje on (paperback) eight nonfiction and fiction Chicana texts. According to Delgadillo, the texts highlight the transformative effect that spiritual mestizaje has on individuals, communities, and societies. The book concludes with a reflection on the polarizing effect of religion in the United States and a call to study alternative texts that demystify religion and critically evaluate theological teachings. tion of Chicano nationalism,” uniting diverse communities in the common fight for land rights, fair wages, educational equality, and political rights. Relying on archival documents, scholarly texts, plays, speeches, music, and protest poetry, Bebout examines the use of imagery and mythology in Chicano narratives. The use of these narratives, he argues, helped solidify and legitimize the Chicano movement throughout the 1960s and 1970s, and also created common ground for Chicanos to unite, organize, and contest Anglo-American cultural hegemony. Bebout particularly highlights United Farm Workers organizer César Chávez’s use of Chicano mythohistorical narratives, images, and culture to promote solidarity among Mexican American farmworkers and how Corky Gonzales’s poem “I Am Joaquín / Yo Soy Joaquín” helped construct identity in the Chicano movement. He concludes with reflections on the use of myths in the Chicano movement today. In this volume, political scientist Karen Kampwirth brings together a wide range of experts—from feminist activists and historians to sociologists and political scientists—­to explore gender in popular politics in Latin America. According to Kampwirth, there have been three waves of populism over the last century: the classical populists, such as Argentina’s Juan gender and Perón and Brazil’s Getúlio Vargas; ­p opulism in neopopulists, like former Perulatin america vian president Alberto Fujimori, edited by Karen Kampwho promoted neoliberal poliwirth, Pennsylvania cies; and present-day “radical” State University Press, populists, such as Venezuelan 2010, 254 pp., $34.95 president Hugo Chávez. Each of (paperback) these waves has interacted with feminist movements in distinct ways, sometimes clashing and other times encouraging women’s organizing. “Populism is potentially a deeply feminist movement, in that women are typically the most excluded of the excluded,” writes Kampwirth in her introduction, noting that the classical populists encouraged women’s struggles for education and the right to vote. However, “the downsides may outweigh the opportunities,” she notes, detailing how the “personalistic nature” and masculine tendencies of many populist leaders can make populism “a risky gamble” for feminists. Gender and Populism in Latin America concludes with an analysis of the opportunities and the constraints that populism creates for gender issues in Latin America, and a reflection on how to overcome these constraints. terrorizing women: ­femi­nicide in the americas edited by Rosa-Linda Fregoso and Cynthia Bejarano, Duke University Press, 2010, 382 pp., $26.95 (paperback) In the past two decades, over 600 women and girls have been killed and over 1,000 disappeared in the Mexican state of Chihuahua alone. Violence against women is also increasing in Argentina, Costa Rica, Guatemala, and Peru. This collection investigates the troubling trend of gender violence in 21 essays and testimonies by human rights activists, attorneys, feminists, and How have feminists organized in Latin America over the past 40 years? In this volume, a variety of women’s scholars, lawyers, and activists analyze this question, painting a vivid picture of feminist cultural and political organizing. The collection is divided into seven parts and 20 chapters covering a variety of issues, including poverty, movement building, LGBT struggles, and religion. Testimonies from activists—such as women’s activArgentina’s Mothers and Grandmothism in latin america and ers of the Plaza de Mayo—give a the caribbean: firsthand account of the struggles that engendering have advanced women’s rights in social justice, the region. Morena Herrera, a former democratizing member of El Salvador’s Farabundo citizenship Martí National Liberation Front edited by Elizabeth Maier (FMLN), highlights the importance and Nathalie Lebon, Rutof international institutions that gers University Press, “increase gender consciousness and 2010, 375 pp., $29.95 provide greater legitimacy to feminist (paperback) discourse and ideas in larger society.” Although the editors, feminist studies professor Elizabeth Maier and anthropologist Nathalie Lebon, celebrate the achievements of feminist struggles, they also examine the challenges ahead. Several chapters analyze the consolidation of anti-choice movements in some countries, including Nicaragua under the left-wing pro-life president Daniel Ortega. The book offers insight into feminist movements in the region, threats to weaken their radical politics, and the backlash from conservative groups. scholars. The editors, Latin American studies professor Rosa Linda Fregoso and criminal justice professor Cynthia Bejarano, argue that feminicide “is rooted in social, political, economic, and cultural inequalities” and is therefore a symptom of failed policies and institutions. “Both the state (directly or indirectly) and individual perpetrators” should be held responsible for the ongoing bloodshed, they write. In particular, Terrorizing Women underlines the “inconsistencies, impunity, apathy, and corruption” of the Mexican criminal justice system, which has allowed feminicide to continue in Mexico unabated. The book also includes testimonies from relatives of women who were killed or disappeared, charts and graphs that provide quantitative analyses of female homicides, and a photo essay on the movement for justice in Chihuahua. SUMMER 2012 NACLA REPORT ON THE AMERICAS 83