Annotated Bib - Anastasia Marie

advertisement

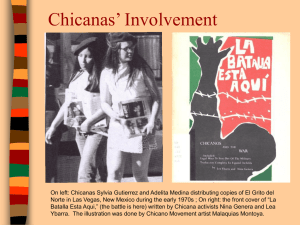

Rigoli 1 Alyssa Rigoli Dr. Dahlberg ENG 4312 April 21, 2015 Annotated Bibliography Anzaldúa, Gloria. "The Homeland, Aztlan." Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. 2nd Ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999: 23-35. Web. 20 Apr. 2015. Anzaldúa focuses on the borderland culture, its origins, and the effects of its existence. She provides in-depth descriptions of what life is like for the Chicanos and other inhabitants of the border between Mexico and the United States, employing intense poetry and narratives to incite empathy and anger. Her obvious use of pathos does not deter the reader from the facts of the chapter. Furthermore, Anzaldúa’s relation of the history of the Chicanos reinforces her claim that they have a right to be where they are and to be treated fairly and equally by the people of the United States. The history of the Chicanos and their beliefs can be used to further my argument about the gender roles of Chicana women. She speaks of the God of War and how he led the people to a place where an eagle, the symbol of masculinity, is eating a serpent, the symbol of femininity. Because of this, the patriarchal family dominates over any matriarchal order. I can use this in my argument to illustrate the immense difficulty that Chicana women have in breaking the gender role that is placed on them by ancient tradition. Beltrán-Vocal, María A. "La problemática de la chicana en dos obras de Sandra Cisneros: "The House on Mango Street y Woman Hollering Creek." Letras Femeninas 21.1/2 (1995): Rigoli 2 139-151. JSTOR. Web. 20 Apr. 2015. Beltrán-Vocal claims that to be a Chicana woman comes with many obstacles and prejudices. She backs up these claims by referencing Sandra Cisneros’ stories about women overcoming gender roles and restrictions: that the main obstacles to acquiring their own identities in the stories are violence, familial oppression, the chauvenism of the Chicano male, the myth of the traditional Chicano woman, the Anglosaxon system, and suffering and selflessness. Beltrán-Vocal emphasizes that women are seen as mothers and wives before they are seen as people. Further, she claims that society holds fast to traditional ways of thinking and tries to avoid any type of change to those traditions, especially if they involve female empowerment. The article will fit perfectly into the support of my argument about the difficulties of breaking the gender roles. The analyses of Cisneros’ works will also serve as ample support for my own analysis of Chayo in “Little Miracles, Kept Promises.” Her discussion of male dominance and female subservience as well as the quest for selfidentity provides contextualization for my analysis of Chayo. Garcia, Alma M. "The Development of Chicana Feminist Discourse, 1970-1980." Gender and Society 3.2 (1989): 217-238. JSTOR. Web. 21 Apr. 2015. Garcia argues that the Chicano Movement of the sixties encouraged the Chicana feminist movement. She states that there has been a history of feminist movements that occurred in response to “the constraints of male domination” within the larger racial movements. She goes into the origins of Chicana feminism and the issues regarding “cultural nationalism” and defines the concept of feminism. Garcia further claims that the rise of Chicana feminists and their criticism of the Chicano movement was seen as a Rigoli 3 threat to the “political unity” of the movement and to the culture itself and provides quotes from leading Chicana feminists to counter this belief. This well-researched essay will prove a great source in my paper. Her numerous quotes from Chicana feminists and loyalists give the arguments and counterarguments that will be reflected in my essay. Chayo’s personal feminist movement in Cisneros’ story causes much the same reaction as seen in Garcia’s essay. The personal assaults in the story against having her own identity are no more emphasized than in the research Garcia provides on the subject. The misunderstanding that feminism undermines tradition is also discussed in Garcia’s paper, giving me the support I need for my essay. Hemmings, Annette. "Navigating Cultural Crosscurrents: (Post)anthropological Passages through High School." Anthropology and Education Quarterly 37.2 (2006): 128-143. JSTOR. Web. 21 Apr. 2015. In Hemmings’ case study, she follows a Chicana American, Christina, as she goes through high school. Her purpose is to attempt to explain how culture affects “adolescent identity formation, academic achievement patterns, and youth cultural productions in high school settings.” She finds that students’ identities are more fluid than fixed, responding to social requirements, parental influence, and cultural responsibilities. Christina is a prime example of rebellion from cultural tradition. She and her friends come from “really strict” families that require them to dress modestly and be abstinent, but they come to school wearing tight clothing and flirt with boys. Hemmings’ study provides real-life examples of young women rebelling from the roles their cultures demand. Chayo’s character is a reflection of the struggles these girls go through to be their own people. My essay will benefit greatly from these examples, Rigoli 4 showing truth in the story. Chayo’s struggle is every Chicana’s struggle; the symbol of that break from tradition is represented in different ways: for Chayo, she cuts her braid; for Christina, she has a secret boyfriend from her parents and refuses to dress the way she “should.” Hitlin, Steven. "Parental Influences on Children's Values and Aspirations: Bridging Two Theories of Social Class and Socialization." Sociological Perspectives 49.1 (2006): 2546. JSTOR. Web. 19 Apr. 2015. Steven Hitlin’s study covers the particular parental influences that affect the occupational, political, and social choices that children make. He argues that family values are often shared among parents and children. Hitlin goes on to say that female career choices are often mediated by mothers’ gender role ideology. Most of his paper discusses the various studies that have been done regarding various parental influences; in regard to gender, he states that most of the studies rely on the father’s influence rather than both parents’. Hitlin’s research emphasizes that a lack of opportunities, combined with cultural norms, makes parents unreceptive or cynical about the desires of their children. I can use his argument to support Chayo’s decision to rebel against the gender role forced on her by her parents, who may have not had the same opportunities as she does now and who do not understand her desires to diverge from the cultural traditions. His views on the influence mothers have on their daughters may serve as an example of the difficulty in breaking the traditions as Chayo did. Wyatt, Jean. "On Not Being La Malinche: Border Negotiations of Gender in Sandra Cisneros's "Never Marry a Mexican" and "Woman Hollering Creek"." Tulsa Studies in Women's Rigoli 5 Literature 14.2 (1995): 243-271. JSTOR. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. Wyatt begins her essay by stating that the Chicano myths of gender are “crystallized” into three icons of femininity: Guadalupe, la Malinche, and La Llorona. She says that Chicana feminist writers declare that they define the identities of contemporary Chicana and Mexican women. Wyatt continues by describing the dual identities of women living on the border. Using Cisneros’ story “Never Marry a Mexican” and interviews from the author, Wyatt makes the assertion that Mexican women—and by the same token, Chicanas—struggle to belong to both America and Mexico and rarely find a balance between them. Then, she goes into deep analysis of Clemencia’s motivations in the story, followed by an equally in-depth analysis of Cleofilas. The introduction of Wyatt’s essay about the icons of femininity can be used to great effect in my own paper. The way Chicanos see Chicanas is through lenses made from those myths, defining the women in ways that they do not deserve. Their identities are stripped from them at birth and replaced with one or all of these icons, depending on the particular family values. The Chicanas’ lives are ruled by the way men see them, not how they see themselves. In truth, their self-identity and self-esteem are greatly affected by these myths. Ybarra, Lea. "When Wives Work: The Impact on the Chicano Family." Journal of Marriage and Family 44. 1 (1982): 169-178. JSTOR. Web. 22 Apr. 2015. Ybarra’s paper focuses on whether or not the employment status of Chicano wives affects the sharing of decision-making, household tasks, and child care with Chicano husbands. Ybarra makes reference to six studies that analyzed the effects of Rigoli 6 Chinana wife employment, several of them stating that there was more involvement of the husband in housework if the wife worked, but that wifely duties were sometimes neglected as a result. She also discusses acculturation as a factor of her analysis, stating that the previously studied conclusion that acculturation determined the conjugal role in Chicano families was contradicted by more recent studies that interviewed the Chicano families, finding that the major impact on conjugal role structure was the wives’ employment rather than acculturation. I find that the studies serve as evidence that what Chayo does in the story will ultimately lead to a better future for herself and for others like her. The break from traditional Chicano gender roles can be beneficial to the family structure in the long-run. It would set a precedent for Chicano families—more specifically the wives—to look to. The search for an identity should not be predicated on the strict views of another person.