maps of mughal india - Rhino Resource Center

advertisement

MAPS OF MUGHAL INDIA

Drawn by Colonel Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil, agent for the French Government to the Court of Shuja-ud-daula at Faizabad, in 1770

SUSAN GOLE

7:

l

.f.ffl

(

i '} !' / )

I

arl: tj,<'l1/1u/c <c . 1u.111om11

·Y'

( o,

If/

(71/

( 11/f'l/.'( , I/(

•'lJ(

..,,

~ "'"""'·'

':/.

Otjo( l

1

""

....

iill ·i11({.I

.:·./~t~:c~~;. ..,._,_·~~ .,'.:,~·:·:

:·t->

·~

...

I

\·~ *-~..:.~~

\;i .. . ~" ' ':-- .. ~· ·~.

I

'

.•

•. '

..:::-:' ..;! .. ·,.

.:-..

!

.. \

.

..

".

·1·.

'!.

__

(

.. __

_,,/

. ' . :J.., . ..:..

•'

/

·' ... ' ''.::;·.:.

::s~;J"':::-~:t.-,/"

•I

. :· . . .....

.

.. : ,. - .... •..

}::~ -~:'~:~·;:~ ~ ~ '··: '~.).~~;

'·'

..

l

.

..

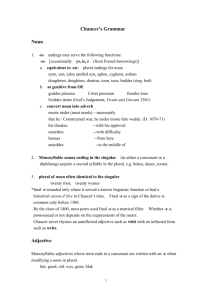

Gentil's map of India from 'Essai sur I'lndoustan ou Empire Mogol', Paris 1785.

MANO HAR

1988

MONG the original works of art made

for Colonel Jean-Baptiste-Joseph Gentil

at Faizabad in 1770 was a finely decorated atlas. For the first time, the map of

India was drawn from an indigenous

source and showed the political divisions of local

-administrative units according to local sources, not

from the garbled accounts o'f foreign visitors. The

twenty-one maps were based on the A'in-i Akbari of

Abu-I Fazl, the detailed record of the country made

for the emperor Akbar, which was available to Gentil

during his long stay at the court of Oudh, and was

shortly after to be translated into English.

Gentil's atlas had no influence on the European

cartography of India, though it contained far more

place names than any other map of the 18th century.

Only two copies existed, the one that is reproduced

here, and which was probably his personal copy,

and a copy that he made after his return to France

and presented to the King for the royal library. It has

been said that the maps are of little geographical

importance since they were based on literary

sources, not on surveys, but in the 18th century very

few parts of the world had been accurately surveyed.

Most maps of India were based on hearsay and a

few stray latitude readings. Maps made from route

marches were begun in Bengal by the British at about

the same time, but there was little accuracy over

most of the country till the triangulation surveys of

the next century. Gentil's maps covered areas that

were hardly known to Europeans till many decades

later, and especially in parts of the north-west, even

the names were known only from the geographical

descriptions, the places themselves being often

inaccessible to Europeans.

The few Mughal maps that have survived are

based on route marches, and were possibly inspired

by foreign maps from the west. There does not seem

to have been any indigenous Indian school of cartography, or even a need for maps. The Hindu,

Buddhist and Jain cosmographies have little to do

with the earth on which we live, though it is possible

that the ancient geographical texts can be shown to

have described actual areas known at the time they

were written. Yet the A'in-i Akbari was written in

such great detail that Gen:til was able to construct

maps in a European style from the lists of places

given in the Persian text. How specific his maps

were can be discovered by comparing them with

those printed on the facing pages, which are details

taken from the most recent French maps available to

Gentil, and which he probably used as a model

while preparing his suba maps. A feature of the

maps by d' Anville that immediately strikes one is the

large area in central India for which no information

was available in France, which d' Anville therefore

.

~

I .~

·· .

I

..

~

'

U: C'Ol.!>NEI. !il~:'.'iTIL.

filled with his various scales of measurement. Gentil's

maps for this same area are covered with names,

and he might have visited some of the towns himself.

Comparison should also be made with the maps

in Irfan Habib's Atlas of the Mughal Empire since they

too show the place-names of the A'in-i Akbari, but on

modem maps, and correctly located. The variation

between the spellings in Gentil's atlas and that of

Habib is large, and may be partly solved by the second

column in the lists at the end of this volume, containing Sarkar's version of the place-names in 1949.

Respectable soldier, good Frenchman

Colonel Gentil spent twenty-five years in India,

and obviously enjoyed the life there. In a letter written

in 1777 to the due de Choiseul in France, Chevalier,

commandant of the French post at Chandemagore,

wrote about Gentil that his long-standing custom of

living among Asiatics had caused him to contract

their manners, so that he had almost lost those of his

native country; yet he did not attempt to deceive by

a seductive exterior, nor spare himself by deviating

from the truth. (The stereotyped European view of

Indian demeanour is apparent at this early date.) Gentil

was popular in Oudh, and particularly so with the

Nawab, Shuja-ud-daula who honoured him with titles

and continually increased his emoluments. When

Gentil's son was publishing his father's memoirs

he had the titles translated by Anquetil du Perron:

Rafi-ud-daula-raised in honour; Nazir Jangcommander in battle; Bahadur-valiant, great warrior;

and Tajbir-ul mulk-counsellor of the Emperor.

Though titles were cheaply earned during this

period, few Europeans were so honoured while

they were in residence there, or received such titles

in genuine regard, not as an act of servility on the

part of an obsequious local ruler.

Gentil went to India in 1752 as an ensign in an

infantry regiment. He had been born at Bagnols in

Languedoc on 25 June 1726 into a military family of

good lineage, but as the youngest of three sons he

had no inheritance, and preferred to travel to India

'to satisfy his curiosity after hearing of the wealth of

the Mughal empire'. We know so much about his

life and background because the biographical entry

for Michaud's Biographic universelle was written by

Louis Langles who knew him personally and who

dedicated his translation of George Forster' s A Journey

from Bengal to England in 1802 to Gentil, with a long

note on his life. In 1814 Gentil's son published a

pamphlet about his father, which was later included

in the Memoires of 1822.

In India, Gentil served with distinction under

Dupleix, de Bussy, Law de Lauriston, de Conflans

and Lally, being promoted to lieutenant in 1760 and

captain ten years later. As Langles wrote, he contributed to French successes, and was also witness to the

reverses. After the English capture of Masulipatam in

1759, Gentil was made prisoner, but soon released

and made his way north to join de Lauriston in time

for the capitulation at Chandemagore. Seeing no

future for the French army in India, Gentil found his

way to the court of the Nawab of Bengal, Mir Kasim,

and offered his services in the fight against the English.

He allied himself with Gourgin Khan, minister to

Kasim, and was ·horrified to see him assassinated

before his eyes. He risked his life attempting to save

the English prisoners at Patna, murdered by Sombre

under the orders of Mir Kasim, and this atrocity

persuaded Gentil to move on to the court of Shujaud-daula, Nawab of Oudh.

There he quickly became a valued friend, and

was chosen to conduct negotiations on behalf of the

Nawab with the English after the battle of Buxar.

The success of this mission increased his prestige

and influence, and he was entrusted with the reorganisation and training of the Nawab's army. He

collected together the French deserters from the

English army and formed them into a corps of 600

men, thus saving many from starvation, and hoping

gradually to lead the Nawab towards an alliance

with the French king. He was appointed the official

French agent at the court of Oudh, and sent home

regular reports on the situation in north India.

As long as Shuja-ud-daula was alive, Gentil

enjoyed a privileged position at the court, a handsome salary, and freedom to indulge his literary and

artistic interests. He kept open house to any who

chose to visit him and spent lavishly from his pocket

to help the needy. He was ill-repaid for this generosity,

however, since many of those he helped were scoundrels, according to Modave in his Voyage du Bengale a

Delhi. In particular, he was harmed by the deeds of a

private French merchant named Debraux who stole

a document dealing with some commercial transactions from Gentil's room, and pretended in Paris

that it was a letter of authority from the Nawab,

seeking an alliance with France. When the letter was

translated and its contents became clear, Debraux

claimed it was written in code. He managed to persuade the minister concerned and was sent out to

India as chief of the French factory at Patna. For his

supposed part in the alliance, Gentil was rewarded

with the Cross of St. Louis. All this, it was claimed,

was done without the knowledge of the French

establishment at Chandernagore or of its head,

Chevalier, though the English at Calcutta learned of

it much sooner. They sought to remove all French

influence from Oudh, especially the presence of

Gentil, whom they saw as the leader through his

close connection with the Nawab. Under the terms

of the treaty made at Allahabad, they were in a position to dictate to the Nawab whom he should employ,

and they were anxious that no other Europeans

should remain. They also learnt that William Bolts,

whom they were hying to have deported from India,

had been in correspondence with Gentil in 1767,

informing him of the confusion in the Company's

affairs in England. The Nawab managed to avoid dismissing Gentil, claiming that he was under obligation

to him for concluding the peace with the English,

and without Gentil to act as go-between he might

not have known the English at all. The Nawab was

able to resist all demands from the English, though

they pressed strongly, and at one stage he had to

agree to dismiss Gentil if a suitable pretext could

be found. After accompanying the Nawab on an

expedition against the Rohillas, Gentil actually took

his leave, but when he learned of Shuja's illness he

hurried back to Oudh, and under the pretence of

seeking audience to take formal leave, he brought a

French physician into the chamber who might have

been able to cure the Nawab. Jealousy in the harem

and among the nobles of the court prevailed, however, and the services of the foreign doctor were

refused. Shuja died on 26 January 1775. Within a

month his successor Asaf-ud-daula had bowed to

the wishes of the English and Gentil was dismissed.

He went to the French settlement at Chandemagore,

and by October 1777 was back in France. So ended

his very fruitful ten years at Oudh. Like many foreigners who spend quarter of a century away from

their country of birth, he found it difficult to settle

back in his own country, and died in poverty on 15

February 1799 at Bagnols.

While at Oudh, Gentil married Therese Velho

in 1772. She was the daughter of Sebastian Velho

and Lucia Mendece and a great niece of Juliana, the

Portuguese lady so powerful at the Delhi court during the first thirty years of the 18th century. Therese

died three months after their arrival in France, but

her mother who had accompanied them lived until

1806. In the disturbances following the French Revolution, Gentil lost the military pension that was

his sole means of livelihood. His life in India had

been spent in collecting literary and historical manuscripts, paintings and coins and these formed the

only wealth he brought back with him. He scorned

an English offer to buy the complete collection for

Rs 120,000, and presented it to his king, whom he

had served so loyally. S. P. Sen traced the beginning

of Indological studies in France to this gift of so

many fine manuscripts and claimed that 'for this

reason alone Gentil deserves to be remembered in

India more than any other Frenchman, more than

Duplei.x, Lally or Bussy, who played such an important part in the political history of the country.'

The manuscript collection

It was perhaps due to the political upheavals in

France after his return that none of Gentil's works

were published during his lifetime. The Memoires

had not been written for publication, but Gentil's

son felt his duty lay in informing the world of his

'virtuous father, respectable soldier and good Frenchman', and so had them published, including with

them various passages from the manuscript works.

Almost all Gentil's bound manuscripts are in the

Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris and they cover a wide

range of interests. Most are dated, and were written

while he was at Oudh. The earliest was a geographical

and historical description of India with the title 'Essai

sur l'Indoustan ou Empire Mogol tire de plusieurs

historiens et geographes lndiens a Faisabad capitale

de la province d'Avad. Par Gentil.' (Cat. no. FR

12,217). It was mainly a translation of the geographical

portions of the text by Abu-I Fazl and though undated

was probably made in 1769, as there is a reference

(page 43) to Shah Alam II having been emperor for

ten years, and living at Allahabad. An addition

made here in different ink states that harassment by

the English has driven the Emperor to withdraw to

Delhi, an event which took place in 1771. The atlas

reproduced here was probably made to accompany

this text, and is dated 1770.

In 1772 Gentil wrote 'Abrege historique des

Souverains de l'lndoustan' (Cat. no. FR 24,219) which

was drawn mainly from Ferishta, beginning with

the flood and concluding with the death of Shujaud-daula and Gentil's move to Chandernagore.

Each page of text is enclosed in double red lines, and

there are numerous paintings of the rulers, though

these are less in the second half, and many are unfinished. At a special audience in June 1778 Gentil

personally presented this manuscript to King Louis

XVI. A copy of his translation of part of the A'in-i

Akbari, again without maps or pictures, is dated

1773. On the title page is 'lndoustan ou Empire Mogol.

A Faizabad 1773, ParM. Gentil, CapitaineenService

de France, dans l'lnde, Chevalier de l'Ordre royal et

militaire de St Louis' (Cat. no. FR 9091). The same

year he also wrote 'Histoire des Pieces de Monnayes

qui ont ete frappees dans l'Indoustan' (Cat. no. FR

25,287), which contained 243 drawings of Indian

coins with their inscriptions and ninety royal portraits. In 1774 he wrote 'Divinites des Indoustans,

tirees des Pourans ou Livres historiques ou Samscretam' (Cat. no. FR 24,220) again embellished with

paintings of the divinities 'with the characters, colours

and bizarre physiognomies that are proper to them'.

After his return to France Gentil made another

copy of his translation from Indian authors and also

redrew the maps he had made for the atlas of 1770.

These were now dispersed throughout the text,

appearing in the appropriate place, and forming a

complete book of geography of India (Cat. no. FR

24,217). He kept the same title 'Essai sur l'lndoustan

ou Empire Mogol .. .' as in the original of 1769,

though the order of the maps was altered so that the

six maps of north-west India followed that of Gujarat

instead of coming last, and the order of the ten maps .

of eastern, central and sou them India varied slightly

within the group. This was presumably done to

focus attention on the north-westerri provinces of

India which were not yet under the control of the

British, especially Sind, where Gentil thought the

French might profitably manufacture cotton goods.

However Gentil did not attempt to copy the drawings which are such an attractive part of the earlier

atlas, though the toponymy is the same. He also

omitted the animals scattered over some of the

maps, replacing them with trees, which were easier

to draw. The date the copy was made is established

by examination of the passage referred to above

about the English harassment of Shah Alam II which

is now incorporated into the text, and the Emperor

is stated to have been ruling for eighteen years, not

ten. This provides a date of 1777, the same year in

which Gentil reached France. So po

the copy during the voyage home.

however, has been altered. In place o

have been added the words 'a VE

Possibly, Gentil felt that his earlier g

library had been ignored, and hopec

would bring an enhanced pecuniary

tion, little knowing that he was soon

the abolition of the monarchy. Thi

worth giving in translation, as it su

life and aims in his own words.

To the King, Sire,

Zeal for the glory of the

during my stay in the Indies tc

might provide some idea of tltries.

The Geography and the

have the honour to present tc

arc the work of several histori

all of the wazir {Aboulfasel) '\'\

been regarded as the wisest

capable minister of this empirE

1 waited, Sire, to place th

your eyes till the moment wh1

have humiliated the enemies·

our commerce in this part

Today, when your glorious rei;

the name of France the greates

parts of the globe, this is the tir

of your victory to enlarge tht

the nation. This volume can

design.

My travels, the twelve ye<

at the court of the grand wazir, r.

that this minister granted me

me in a position to provide tt

and most exact information th

Your Majesty will care to cast~

this work, you will see what ad

ministers might sain from b

opening new centres, especia

vince of Tatta where cloth for F:

produced; in this way the ne

much gold and silver to India mi

and the circulation of curre

more plentiful in a kingdom of

the delight and the glory.

Gentil's signature follows the usual fe

There is one more manuscript all

and this, like the atlas, has recently fc

England. In 1980 the Victoria and A

acquired a volume titled 'Recueil de le

Dessins sur Jes Usages et Coutumes c

l'Indoustan ou Empire Mogol, d'a1

peintres Indiens NEV ASILAL, MC

he Nawab towards an alliance

g. He was appointed the official

court of Oudh, and sent home

1e situation in north India.

uja-ud-daula was alive, Gentil

d position at the court, a hand·edom to indulge his literary and

e kept open house to any who

1d spent lavishly from his pocket

:! was ill-repaid for this generosity,

1 of those he helped were scoun,foda vein his Voyage du Bengalea

he was harmed by the deeds of a

:hant named Debraux who stole

with some commercial transacroom, and pretended in Paris

of authority from the Nawab,

vith France. When the letter was

ontents became clear, Debraux

en in code. He managed to perconcerned and was sent out to

French factory at Patna. For his

e alliance, Gentil was rewarded

. Louis. All this, it was claimed,

the knowledge of the French

'handernagore or of its head,

1e English at Calcutta learned of

?Y sought to remove all French

:ih, especially the presence of

saw as the leader through his

th the Nawab. Under the terms

~Allahabad, they were in a posi~awab whom he should employ,

fous that no other Europeans

y also learnt that William Bolts,

ing to have deported from India,

pondence with Gentil in 1767,

1e confusion in the Company's

1e Nawab managed to avoid disting that he was under obligation

ng the peace with the English,

to act as go-between he might

! English at all. The Nawab was

1ands from the English, though

;ly, and at one stage he had to

mtil if a suitable pretext could

:ompanying the Nawab on an

1e Rohillas, Gentil actually took

he learned of Shuja's illness he

dh, and under the pretence of

take formal leave, he brought a

:o the chamber who might have

~ Nawab. Jealousy in the harem

les of the court prevailed, howces of the foreign doctor were

nn ?f.. hn11~n1

177'i. Within

i1

month his successor Asaf-ud-daula had bowed to

the wishes of the English and Gentil was dismissed.

He went to the French settlement at Chandemagore,

and by October 1777 was back in France. So ended

his very fruitful ten years at Oudh. Like many foreigners who spend quarter of a century away from

their country of birth, he found it difficult to settle

back in his own country, and died in poverty on 15

· February 1799 at Bagnols.

While at Oudh, Gentil married Therese Velho

in 1772. She was the daughter of Sebastian Velho

and Lucia Mendece and a great niece of Juliana, the

Portuguese lady so powerful at the Delhi court during the first thirty years of the 18th century. Therese

died three months after their arrival in France, but

her mother who had accompanied them lived until

1806. In the disturbances following the French Revolution, Gentil lost the military pension that was

his sole means of livelihood. His life in India had

been spent in collecting literary and historical manuscripts, paintings and coins and these formed the

only wealth he brought back with him. He scorned

an English offer to buy the complete collection for

Rs 120,000, and presented it to his king, whom he

had served so loyally. S. P. Sen traced the beginning

of Indological studies in France to this gift of so

many fine manuscripts and claimed that 'for this

reason alone Gentil deserves to be remembered in

India more than any other Frenchman, more than

Dupleix, Lally or Bussy, who played such an important part in the political history of the country.'

The manuscript collection

It was perhaps due to the political upheavals in

France after his return that none of Gentil's works

were published during his lifetime. The Memoires

had not been written for publication, but Gentil's

son felt his duty lay in informing the world of his

'virtuous father, respectable soldier and good Frenchman', and so had them published, including with

them various passages from the manuscript works.

Almost all Gentil's bound manuscripts are in the

Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris and they cover a wide

range of interests. Most are dated, and were written

while he was at Oudh. The earliest was a geographical

and historical description of India with the title 'Essai

sur l'Indoustan ou Empire Mogol tire de plusieurs

historiens et geographes lndiens a Faisabad capitale

de la province d' Avad. Par Gentil.' (Cat. no. FR

12,217). It was mainly a translation of the geographical

portions of the text by Abu-I Fazl and though undated

was probably made in 1769, as there is a reference

(page 43) to Shah Alam II having been emperor for

ten years, and living at Allahabad. An addition

made here in different ink states that harassment by

the Enelish has driven the Emperor to withdraw to

Delhi, an event which took place in 1771. The atlas

reproduced here was probably made to accompany

this text, and is dated 1770.

In 1772 Gentil wrote 'Abrege historique des

Souverains de l'Indoustan' (Cat. no. FR 24,219) which

was drawn mainly from Ferishta, beginning with

the flood and concluding with the death of Shujaud-daula and Gentil's move to Chandernagore.

Each page of text is enclosed in double red lines, and

there are numerous paintings of the rulers, though

these are less in the second half, and many are unfinished. At a special audience in June 1778 Gentil

personally presented this manuscript to King Louis

XVI. A copy of his translation of part of the A'in-i

Akbari, again without maps or pictures, is dated

1773. On the title page is 'Indoustan ou Empire Mogol.

A Faizabad 1773, Par M. Gentil, Capitaine en Service

de France, dans l'Inde, Chevalier de l'Ordre royal et

militaire de St Louis' (Cat. no. FR 9091). The same

year he also wrote 'Histoire des Pieces de Monnayes

qui ont ete frappees dans l'lndoustan' (Cat. no. FR

25,287), which contained 243 drawings of Indian

coins with their inscriptions and ninety royal portraits. In 1774 he wrote 'Divinites des lndoustans,

tirees des Pourans ou Livres historiques ou Samscretam' (Cat. no. FR 24,220) again embellished with

paintings of the divinities 'with the characters, colours

and bizarre physiognomies that are proper to them'.

After his return to France Gentil made another

copy of his translation from Indian authors and also

redrew the maps he had made for the atlas of 1770.

These were now dispersed throughout the text,

appearing in the appropriate place, and forming a

complete book of geography of India (Cat. no. FR

24,217). He kept the same title 'Essai sur l'Jndoustan

ou Empire Mogol ... ' as in the original of 1769,

though the order of the maps was altered so that the

six maps of north-west India followed that of Gujarat

instead of coming last, and the order of the ten maps

of eastern, central and southern India varied slightly

within the group. This was presumably done to

focus attention on the north-western provinces of

India which were not yet under the control of the

British, especially Sind, where Gentil thought the

French might profitably manufacture cotton goods·.

However Gentil did not attempt to copy the drawings which are such an attractive part of the earlier

atlas, though the toponymy is the same. He also

omitted the animals scattered over some of the

maps, replacing them with trees, which were easier

to draw. The date the copy was made is established

by examination of the passage referred to above

about the English harassment of Shah Alam 11 which

is now incorporated into the text, and the Emperor

is stated to have been ruling for eighteen years, not

ten. This provides a date of 1777, the same year in

which Gentil reached France. So possibly he made

the copy during the voyage home. The title page,

however, has been altered. In place of Gentil's name

have been added the words 'a Versailles, 1785.'

Possibly, Gentil felt that his earlier gifts to the royal

library had been ignored, and hoped that this book

would bring an enhanced pecuniary benefit or position, little knowing that he was soon to lose all with

the abolition of the monarchy. The dedication is

worth giving in translation, as it sums up Gentil's

life and aims in his own words.

To the King, Sire,

Zeal for the glory of the nation led me

during my stay in the Indies to collect all that

might provide some idea of these vast countries.

The Geography and the maps which I

have the honour to present to Your Majesty

are the work of several historians, but above

all of the wazir (Aboulfasel) who has always

been regarded as the wisest and the most

capable minister of this empire.

I waited, Sire, to place this work before

your eyes till the moment when your armies

have humiliated the enemies ever jealous of

our commerce in this part of the world.

Today, when your glorious reign has given to

the name of France the greatest renown in all

parts of the globe, this is the time to make use

of your victory to enlarge the commerce of

the nation. This volume can help fulfil this

design.

My travels, the twelve years that I spent

at the court of the grand wazir, and the honour

that this minister granted me there, placed

me in a position to provide the most recent

and most exact information that we have. If

Your Majesty will care to cast your eyes over

this work, you will see what advantages your

ministers might gain from business, from ,

opening new centres, especially in the province of Tatta where cloth for France might be

produced; in this way the need to send so

much gold and silver to India might be avoided

and the circulation of currency rendered

more plentiful in a kingdom of which you are

the delight and the glory.

Gentil's signature follows the usual felicitations.

There is one more manuscript album by Gentil,

and this, like the atlas, has recently found its way to

England. In 1980 the Victoria and Albert Museum

acquired a volume titled 'Recueil de toutes sortes de

Dessins sur Jes Usages et Coutumes des Peuples de

l'lndoustan ou Empire Mogol, d'apres plusieurs

peintres lndiens NEV ASILAL, MOUNSINGUE,

u Nabob Visio Soudjaadaula, Gou:fes provinces d'Eleabad et d' Avad,

te fait par les soins du Sr GENTIL

?rie, en 1774, a Faisabad.' Here, on

are many of the paintings already

, the 'Abrege historique' and the

; and deities. Yet each drawing is

:. For example, the two fighting

::aboul map have different stances

md the strongmen of the Eleabad

gorous and alive than the similar

1eil'. The volume appears to be a

>llection of the paintings that Gentil

~ most expressive in his attempt to

eh government and people about

re.

:>lio volume is about the same size as

1tains paintings on one side of the

1e facing pages, manuscript notes

hands have been pasted in. Many

kal with the text published in the

~ntil's son in 1822; others are

~ figures in the pictures. It is likely

m to France, Gentil assembled his

ntinuous narrative, combining his

with the geographical and histori:the country that he had translated

ors, and it is this manuscript that

; in 1822, and did not return, and

•n paper to be pasted into the 'Re:;entil or by his son. Som~ of the

certainly seem to be in Gentil' s

in the 'Recueil' follow a rational

st part deals with life at the court,

I durbar, ladies in the harem gar1ousehold staff (each one carefully

f transport, and the royal hunt and

;times. The second half covers the

s of India, and their practices and

lso includes sections on weapons

ere are also two pictures of Gentil

he is fair-skinned in European

.ong red coat, being presented to

1e Nawab. On f.17 he is part of the

al Carnac and is indistinguishable

>uring from the other emissaries

daula. A note below states that he

so that he might travel more easily

ryside. In both pictures the style is

we thus get little idea of what

>kcd like. Fortunately, we have a

P. Boudier, which was used as a

Memoires in 1822.

e manuscripts listed above, Gentil

l large number of Indian miniature

..... ""' ...... _:_,.,. •-

l~A•~..-. l~rtn1t-:.,n.oc-

I-lo

excellent milk, and hoped they might be cross-bred

for use in France.

In a Memoire (in manuscript) dated 25 May 1778

that Gentil sent to Paris soon after reaching France

in order to secure his pension, he named as one of

his achievements 'travailler pour la litterature',

since he had collected all the manuscripts he could

lay his hands on which might one day aid him in

writing a full history of Hindustan, and wrote that

the Geography accompanied by twenty-one maps

'ne laissent rien a desirer' (leave nothing to be

desired) for the knowledge of this empire, since

they were made on the spot according to local geographies. Unfortunately his plans did not mature,

as there is no record of his having assembled all his

material into a comprehensive history, and we have

only the manuscript volumes listed above and the

Memoires published later by his son.

The title page of the Memoires sur l'lndoustan, ou

Empire Mogol gave Gentil's full credentials as author:

'M. Gentil, ancien colonel d'infanterie, Chevalier de

I' ordre royal et militaire de Saint-Louis, resident

franc;ais aupresdu premiervezyrdel'empire, nabab

et souverain d' Aoude, d'Eleabad, etc, Choudja-aed-doulah, general des troupes mogoles au service

de ce prince, etc.' The octavo volume was published

had employed three Indian artists at Oudh and it is

difficult to know how many of these miniatures were

copied on his orders, and how many he bought

or collected while he was there. They are in the

Cabinet des Estampes at the Bibliotheque Nationale,

bound in several volumes. They cover a wide range

of subjects and possibly supplied the originals for

the royal portraits in the 'Abrege historique' and the

decoration to the atlas maps. Before Gentil's return

the royal library held a total of 124 Indian manuscripts, according to the leading French scholar of

Indian studies, Anquetil du Perron. Gentil' s gift of

133 manuscripts in Persian, Arabic, Sanskrit,

Marathi, Bengali and Tamil thus more than doubled

the collection. He also donated his collection of

arms, a. large number of coins, thirty-five of them

gold, and some medals depicting the Emperors. He

was interested in objects of natural history, and dispatched from India twelve ewes and six rams from

Tibet, the type whose wool was used for the famous

shawls of Kashmir. They reached as far as the Ile-deFrance, while the musk-deer that he sent went further,

and was the only one of its kind to reach the zoo at

Versailles alive. He also sent to He de Bourbon four

cows and two bulls from Gujarat as he found them

cheap to maintain while giving ;:i large quantity of

.

----------,...-...-·"'""°~,- '·.-·,-_-~.:c-.

- '

· :: f~!{"(·:~~~~-~¥:.riili

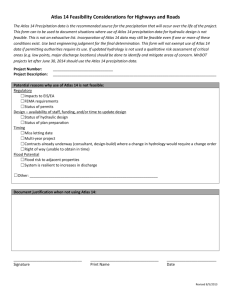

The title page to Gentil' s Atlas. Compared to the neat work on the maps, the design here is crude. The paper with lettl'ring

has been pasted on the page, and the outline added later. At the bottom Gentil's name has been erased and the title

'Colonel' written in its place. The smudges are in the original. Though Gentil's Mughal seal was stamped correctly on the

r<•v<>rc: nf th<> :otl:ac: it ic: invPrlPd hPrP Pnc;c;ihlv th<• 1.\'holv n,,pp "'a<: alt .. rPd at a lat.•r ""'" hv r..-ntil'c:: c::nn

in Paris by Petit of the Palais-Royal, Galeries de Bois,

and contained over 400 pages. It was dedicated 'A la

Memoirc de Choudja-a-ed-doulah. D fut constamrnent

I'ami et le protecteur des franc;ais', to Shuja-uddaula, ever the friend and protector of the French.

In addition to the portrait of Gentil by Boudier, it

contained portraits of Nadir Shah and Shuja-uddaula, and also an anonymous map of India, made

entirely in the European style of the day, with no

influence from Gentil's maps.

After a brief geographical and historical description of the Deccan the first chapter outlined the

political situation in south India, and the French

struggles there against the British. The second chapter

concerned Thomas Quli Khan-the European name

for Nadir Shah--and his 'conquest of India'. Chapters

three and four dealt with the situation in Bengal and

events in the life of Shuja-ud-daula. The fifth chapter

described an event of 1788, when, in Paris, Gentil

was appointed interpreter and guide to the emissaries sent by Tipu Sultan. This was followed by a

short chapter on Warren Hastings, whom Gentil

had tried to assist during the impeachment by writing

letters to London. The book closed with sketches of

five women who had played an important role in

India: Razia, Nur Jahan, Jahanara, Juliana, and

Begum Samru. Appendixes added by Gentil's son

gave accounts from others, such as Langles and

Anquetil du Perron, letters and citations, lists of

items brought back by Gentil, and additional information thought relevant by his son. The book seems

to have had little success, since it remained almost

unknown. In a paper read at the tenth public meeting of the Indian Historical Records Commission

held at Rangoon in December 1927, Sir Evan Cotton

summarized the book, adding comments on matters

omitted by Gentil and highlighting the English view

of certain events. Cotton expressed surprise that

the book was so little known, even by those writing

specifically about events at which Gentil was present,.

Possibly the book had appeared too long after the

events which it described, and in the interim the

French people had been occupied with other

momentous affairs.

European map-making

The European maps of India available to travellers at this time were more suited to giving a general

idea of the country than for finding a particular place

or route. India had been shown on maps since the

days of Ptolemy and the early circular world maps,

but rarely in a recognisable shape. Marco Polo's

account added more modem names, and the early

mariners' reports brought the triangular shape that

we know today. In 1619 a detailed map of north

India was made bv William Baffin under the guidance

of Sir Thomas Roe, who had been sent as ambassador

by the EngJish King to the court of Jahangir. Dutch

and French maps during the 17th century gradually

added more detail. As individual travellers returned

home and published their journals, the cartographers in Europe attempted to fit the towns, rivers and

mountains into the existing outlines. Measurements

were vague and rarely meant the same distance in

all parts of the country. The names, too, were hard

for Europeans to transcribe into their own language,

and this problem was compounded when they were

translated within the languages of Europe. It sometimes happened that the same place occurred twice

on the map with a different spelling, thus appearing

to be two different places.

In the first half of the 18th century war between

t~e English and the French in south India emphasised t~e need for better maps, and army engineers

were given the task of surveying the route through

which the army had marched, or where the battle

was expected to be fought. This development came

later to the north and it was not until the British had

gained large tracts of territory that actual surveys

were begun. James Rennell was appointed the first

Surveyor General of Bengal in 1767, but his map of

the whole of India was not published until after his

return to England, in 1782. The first map based on

his surveys was of Bengal and Bihar in 1776, with an

extension as far as Delhi the following year. Soon

the value of correct maps was apparent to the revenue

collectors, and as the British acquired territory, so

their maps became more detailed and covered wider

areas. The triangulation surveys were begun in 1802

in the south, and by the middle of the century had

spread over most of the sub-continent.

If Gentil had a map of India with him when he

was at Oudh it would probably have been the large

four sheet map drawn by J.B.B.d' Amrille in 1752. This

was on a scale of 17 French leagues of 2500 yards

(about 60 miles) to an inch, and there were many

large areas completely blank, for which d' Anville

had no reliable information. To the north it went

hardly eighty miles beyond Delhi and except for two

short routes into Rajasthan there was nothing north

of a line from Delhi to Somnath. For information

about the lndus river and the northern part of India

the reader was directed to the same author's map of

Asia, on an even smaller scale.

D' Anville's map of India showed six different

scales of measurement. Two were French, the French

league of 2500 yards and the marine league of 20 to a

degree. The other four were all Indian, different

versions of the cos. There was the cos of the minars

between Agra and Delhi, equal to 1335 yards, the

large cos of 33 to a degree, the common cos of 37 to a

degree, and the 'gos' or 'gau', a nautical measure

from the coasts of Malabar and Coromandel, which

was four times the length of the northern cos. In his

text Gentil wrote that a cos equalled three-quarters

of a league of 25 to a degree. However he was aware

of the difficulties he faced in making his maps, without any accurate surveys on which to base them, or

even detailed route journals. In the atlas of 1785 he

added a Note:

In the maps shown here, the author has

included only the most important towns,

market-towns and villages or aldees in the

circars or parganas. Their position cannot be

correct, as he has located them in accordance

with the Indian geographies which are texts

only, and have no maps. This means they

also have no scale. The size of each province

follows the Ayin-i Akbari, as do their boundaries and their produce. The intention in

making the maps was to give the best possible

idea of the country to the Ministers, and to

show them how important it is that France

does not permit the further strengthening of

English power there. (page 238)

Since many of the words he used were new to

him, Gentil was careful to define their meanings. A

soubah was a large area with a governor-general,

called a soubahdar. A drear was an area containing

between three and 50 parganas. A pargana was smaller

and contained between three and 50 aldees. An a/dee

was a village whose size depended upon the

number of bigahs it held. A bigalz was a field of 80

square yards. A yard was estimated at 3 feet 2

inches.

Colonel Gentil's Atlas

As can be seen from the title page, Gentil made

this atlas while he was at Faizabad, in 1770. It is thus

one of his earliest works. He had already been at

Faizabad for about five years by the time the date

was written, but there is no reference as to how long

he had been working on it, or who else had been

employed on it with him. Translation of part of the

Ain-i Akbari had been included in the Essai sur

l'Indoustan' of 1769, and it is presumed that the

atlas was made to ac.company and illustrate this text.

The original Persian manuscript that he used is possibly one of those he deposited with the royal library

after his return to France. In addition, he used other

untraced manuscripts for the southern part of India

of which the sarkars and parganas had not been

listed by Abu-I Fazl.

The atlas is oblong in shape, 55 cm by 38 cm.

The sheets were loose when they were painted or

inscribed, but were then bound by pasting a band

of blue silk along one of the shorter edges of the

paper, and then this silk strip was stitched with six

stitches to hold the sheets together. They were then

bound within two quite thick boards which were

covered with patterned blue silk cloth. The paper is

European with a fleur de lys and crown watermark.

There is no identifying maker's name or mark, but

similar watermarks are found in French and English

books of the 1760s, especially on paper used for

maps (Heawood Watermarks, 1950, no. 1743 is the

nearest). A note on the back cover reads '42 feuille',

and the page number at the top centre of the last

map, that of Lahore, is '83 et dernier'. That means

that there were 42 folios, and page 83 was the last,

with its verso blank. Another set of numbers is in

lighter ink at the upper comers of the pages; they

run from 12 through to 98, omitting 14-15 and 20-21,

so perhaps Gentil planned an introduction or text

which he later omitted. The title page is not included

in either set of numbering, and was probably added

after the other pages were complete. It is inscribed

with heavy black ink, 'Empire Mogol divise en 21

soubas ou Gouvemements tire de differens ecrivains

du pals a Faisabad MDCCLXX'. Below is Gentil's

Persian seal, but next to it his name has been crudely

erased, and 'Colonel' put in its place (he was

awarded this rank after his return to France, in

1778). The seal appears three times, here where it is

upside down, and correctly inside the front and

back covers. Next to it on the front cover is the

inscription 'Cet atlas appartient aMr Gentil l'indien'

(This atlas belongs to Monsieur Gentil the Indian)

and just below it is his signature and 'l'indien'

repeated, this time in brackets.

On the verso of the title page is a list of the maps

with their page numbers written in ink; to the left of

these numbers is another column in pencil referring

to the pages which have text only. This table of contents is on blue paper and has been pasted on the

outer half of the page. The inner half contains coi_ns

of the various Indian dynasties, as do folios 2, 2

verso, and 4 verso. These coins are beautifully

drawn, both sides shown, each with a gold rim, and

the name of the king in French below. The numbering is from right to left, suggesting that they were

designed and drawn by a Persian-speaking person,

not Gentil himself. The dates of each are given

according to A.H., not A.D. All the pages are

inscribed on one side only, except the verso of the

title page, two pages with coins as noted above, and

folio 14 verso where the long list of subas in Bengal

requires two pages. Each map folio is preceded by a

folio listing the sarkars and parganas which are to be

found in the map and which have been translated

from the Indian texts. The handwriting is fairly clear

though some letters are difficult to distinguish, and

often they seem to be rather carelessly written. For

example, frequently the crossb

omitted, so that it is read as an 'I

torn in half vertically, apparen

use, since there were insufficiE

Kabul to fill a whole page-poss

this size was difficult to obtain.

inadvertently tom horizontally,

third is missing, and along with

Blank blue paper has been pasted

sing portion. The number of coh

varies, as many as twelve on th•

Bengal, and six on the page for A

text pages have been filled wit

usually birds or plants, similar in

adorn the map pages. Alongside

bad is a plan of the fort of Alla

probably been supplied by Josep

it appears also in his Beschreibun

1785. All the names translated b'

copied as he wrote them, and pi

this volume. The maps have bee

in size in this reproduction. ThE

the total painted area and the dim

portion have been given below

folio.

The coastline of Gentil's maF

that of d' Anville's map of India oJ

noticeable in the map of Hydera

the whole of south India. In ne

mountain ranges correctly place

better knowledge of the river syst

rally, since he had no facilities fc

are far from correctly drawn. D' A

larly short of information for cen

most of it completely blank. Intl

d' Anville's map did not extend to

as it was then, even though the

would have permitted this. In th

was reticent about his own m

India, except during the military

south, so we have little knowledg•

he travelled, or even by which ro

after the French defeat in south:

record that he visited the Mughc

jahanabad, though he must surei

ous to see it. When he was forced

he was, according to the Memoir•

post with the emperor, which he c

the weak positon of the empire b)

was no doubt sad to leave Faizaba

that his twenty-five years in Indic

period, and time well-spent.

Company painting in Oudh

'As there was no potentate in·

in such splendid style as he, and a

had been sent as ambassador

the court of Jahangir. Dutch

g the 17th century gradually

idividual travellers returned

heir journals, the cartograed to fit the towns, rivers and

:ing outlines. Measurements

meant the same distance in

The names, too, were hard

ibe into their own language,

impounded when they were

nguages of Europe. It somee same place occurred twice

ent spelling, thus appearing

'5.

1e 18th century war between

:nch in south India empha~ maps, and army engineers

urveying the route through

arched, or where the battle

;ht. This development came

Nas not until the British had

?rritory that actual surveys

nell was appointed the first

lgal in 1767, but his map of

lot published until after his

'82. The first map based on

d and Bihar in 1776, with an

ti the following year. Soon

was apparent to the revenue

ritish acquired territory, so

detailed and covered wider

surveys were begun in 1802

·middle of the century had

;uh-continent.

of India with him when he

·obably have been the large

J.B.B.d'Anville in 1752. This

?nch leagues of 2500 yards

1ch, and there were many

Jlank, for which d' Anville

tion. To the north it went

nd Delhi and except for two

an there was nothing north

Somnath. For information

:I the northern part of India

o the same author's map of

scale.

India showed six different

wo were French, the French

the marine league of 20 to a

were all Indian, different

? was the cos of the minars

i, equal to 1335 yards, the

a.a....---_... ...... __ ,.-.C' " ' ~7 tn ~

from the coasts of Maia bar and Coromandel, which

was four times the length of the northern cos. In his

text Gentil wrote that a cos equalled three-quarters

of a league of 25 to a degree. However he was aware

of the difficulties he faced in making his maps, without any accurate surveys on which to base them, or

even detailed route journals. In the atlas of 1785 he

added a Note:

In the maps shown here, the author has

included only the most important towns,

market-towns and villages or aldees in the

circars or parganas. Their position cannot be

correct, as he has located them in accordance

with the Indian geographies which are texts

only, and have no maps. This means they

also have no scale. The size of each province

follows the Ayin-i Akbari, as do their boundaries and their produce. The intention in

making the maps was to give the best possible

idea of the country to the Ministers, and to

show them how important it is that France

does not permit the further strengthening of

English power there. (page 238)

Since many of the words he used were new to

him, Gentil was careful to define their meanings. A

soubah was a large area with a governor-general,

called a soubahdar. A drear was an area containing

between three and 50 parganas. A pargana was smaller

and contained between three and 50 aldees. An a/dee

was a village whose size depended upon the

number of bigahs it held. A bigah was a field of 80

square yards. A yard was estimated at 3 feet 2

inches.

Colonel Gentil's Atlas

As can be seen from the title page, Gentil made

this atlas while he was at Faizabad, in 1770. It is thus

one of his earliest works. He had already been at

Faizabad for about five years by the time the date

was written, but there is no reference as to how long

he had been working on it, or who else had been

employed on it with him. Translation of part of the

Ain-i Akbari had been included in the Essai sur

l'Indoustan' of 1769, and it is presumed that the

atlas was made to accompany and illustrate this text.

The original Persian manuscript that he used is possibly one of those he deposited with the royal library

after his return to France. In addition, he used other

untraced manuscripts for the southern part of India

of which the sarkars and parganas had not been

listed by Abu-I Faz).

The atlas is oblong in shape, 55 cm by 38 cm.

The sheets were loose when they were painted or

inscribed, but were then bound by pastin~ a band

paper, and then this silk strip was stitched with six

stitches to hold the sheets together. They were then

bound within two quite thick boards which were

covered with patterned blue silk cloth. The paper is

European with a fleur de lys and crown watermark.

There is no identifying maker's name or mark, but

similar watermarks are found in French and English

books of the 1760s, especially on paper used for

maps (Heawood Watermarks, 1950, no. 1743 is the

nearest). A note on the back cover reads '42 feuille',

and the page number at the top centre of the last

map, that of Lahore, is '83 et demier'. That means

that there were 42 folios, and page 83 was the last,

with its verso blank. Another set of numbers is in

lighter ink at the upper comers of the pages; they

run from 12 through to98, omitting 14-15and 20-21,

so perhaps Gentil planned an introduction or text

which he later omitted. The title page is not included

in either set of numbering, and was probably added

after the other pages were complete. It is inscribed

with heavy black ink, 'Empire Mogol divise en 21

soubas ou Gouvemements tire de differens ecrivains

du pa1s a Faisabad MDCCLXX'. Below is Gentil's

Persian seal, but next to it his name has been crudely

erased, and 'Colonel' put in its place (he was

awarded this rank after his return to France, in

1778). The seal appears three times, here where it is

upside down, and correctly inside the front and

back covers. Next to it on the front cover is the

inscription 'Cet atlas appartient aMr Gentil l'indien'

(This atlas belongs to Monsieur Gentil the Indian)

and just below it is his signature and 'l'indien'

repeated, this time in brackets.

On the verso of the title page is a list of the maps

with their page numbers written in ink; to the left of

these numbers is another column in pencil referring

to the pages which have text only. This table of contents is on blue paper and has been pasted on the

outer half of the page. The inner half contains coins

of the various Indian dynasties, as do folios 2, 2

verso, and 4 verso. These coins are beautifully

drawn, both sides shown, each with a gold rim, and

the name of the king in French below. The numbering is from right to left, suggesting that they were

designed and drawn by a Persian-speaking person,

not Gentil himself. The dates of each are given

according to A.H., not A.O. All the pages are

inscribed on one side only, except the verso of the

title page, two pages with coins as noted above, and

folio 14 verso where the long list of subas in Bengal

requires two pages. Each map folio is preceded by a

folio listing the sarkars and parganas which are to be

found in the map and which have been translated

from the Indian texts. The handwriting is fairly dear

thou eh some letters are difficult to distinITTJish. and

example, frequently the crossbar of 't' has been

omitted, so that it is read as an 'I'. Folio 38 has been

tom in half vertically, apparently for some other

use, since there were insufficient names in suba

Kabul to fill a whole page-possibly good paper of

this size was difficult to obtain. Folio 28 has been

inadvertently tom horizontally, so that about one

third is missing, and along with it some of the text.

Blank blue paper has been pasted to replace the missing portion. The number of columns to each page

varies, as many as twelve on the crowded page of

Bengal, and six on the page for Ajmir. Spaces in the

text pages have been filled with small drawings,

usually birds or plants, similar in style to those that

adorn the map pages. Alongside the suba of Allahabad is a plan of the fort of Allahabad, which had

probably been supplied by Joseph Tieffenthaler, as

it appears also in his Besclireibung von Hindustan of

1785. All the names translated by Gentil have been

copied as he wrote them, and placed at the end of

this volume. The maps have been slightly reduced

in size in this reproduction. The original width of

the total painted area and the dimensions of the map

portion have been given below the notes to each

folio.

The coastline of Gcntil's maps mainly followed

that of d' Anville's map of India of 1752. This is most

noticeable in the map of Hyderabad which covers

the whole of south India. In neither map are the

mountain ranges correctly placed, but Gentil had

better knowledge of the river systems, though naturally, since he had no facilities for surveying, they

are far from correctly drawn. D' Anville was particularly short of information for central India, and left

most of it completely blank. In the north-west too,

d' Anville's map did not extend to the limits of India

as it was then, even though the size of his paper

would have permitted this.· In the Memoires Gentil

was reticent about his own movements within

India, except during the military campaigns in the

south, so we have little knowledge about how much

he travelled, or even by which route he went north

after the French defeat in south India. There is no

record that he visited the Mughal capital of Shahjahanabad, though he must surely have been curious to see it. When he was forced to leave Faizabad,

he was, according to the Memoires, offered a good

post with the emperor, which he declined, knowing

the weak positon of the empire by then. Though he

was no doubt sad to leave Faizabad, he probably felt

that his twenty-five years in India had been a good

period, and time well-spent.

Company painting in Oudh

'As thPrP was no notPntatP in anv countrv livinP

I

wealth, rank, and Javish diffusion of money in every

street and market, artisans and scholars flocked hither

from Dhaka, Bengal, Gujrat, Malwah, Haidera-bad,

Shahjahanabad,

Lahaur,

Peshawar,

Kabul,

Kashmir and Mullan.' This is how Muhammad Faiz

Bakhsh d~scribed the court of Shuja-ud-daula at

Faizabad. The splendour of the Mughal court at

Agra and Delhi was gone by the middle of the 18th

century, and Delhi itself was in ruins after the devastating raids of the Rohillas. So Shuja-ud-daula

became the leading patron of the arts in north India.

As Gentil narrated it, Shuja-ud-daula was the

maternal grandson of Sa' adat Khan, Governor of

Agra and Viceroy of Oudh under the Emperor Farrukhsiyar. Shuja's father Safdarjang was Sa'adat

Khan's nephew and son-in-law, and succeeded to

his titles. He was made vazir in 1747 when Ahmed

Shah came to the throne, but the jealousy of Ghaziud-din Khan drove him to retire to his estates where

he died in 1754. Shuja succeeded to the title of Mir

Atish, and to the suba of Arig, Oudh and Allahabad.

Other historians may differ, but this is how Gentil

heard it at Faizabad.

In 1765, after the treaty with the British at

Allahabad, Shuja moved his capital from Lucknow

to Faizabad, and set about building a city worthy of

his name. On his death, however, his son returned

to Lucknow, and Faizabad was left to decay after its

brief period of splendour. There is no record of painting at Lucknow in the first half of the century, and

the work of any artists there were was probably

indistinguishable from the imperial style at Delhi.

There is an album of 115 paintings in the Victoria

and Albert Museum (1.5. 48-1956) that was presented

to Lord Clive by Shuja-ud-daula in about 1765-67,

the time that Gentil began his employment there.

No European influence is apparent in the paintings

which are mainly portraits and flowers, and no

record of who painted them. Yet within five years

Gentil was able to acquire series of albums full of

paintings in the style he wanted. Mildred Archer, in

her notice about the Gentil atlas in the IOL Report

for 1978, has described the artistic milieu at

Faizabad:

At the time when Gentil was living in

Faizabad, Oudh was culturally in a flourishing

state. After the troubles in Delhi during 1759

to 1761, many Delhi families including writers

and artists had moved there. This was a great

period of Urdu poetry when Mirza Muhammad Rafi Sauda, Mian Hazrat and Ashraf

Ali Khan were writing. Painting also was

flourishing. The Nawab and nobility were

patronising artists and many portraits and

genre scenes were being produced in a dis-

tinctive style. Elongated figures in white

jamns were shown sitting on terraces or walking

in gardens with ladies as gay as the parterres

of flowers through which they strolled.

Faizabad was an ideal centre for Gentil who

took a Jively interest in Indian life and culture.

Dr Archer goes on to describe the paintings that

surround the maps in GentiJ's atlas:

Sty1istically they are very close to other

drawings in the Library's collection-those

commissioned in neighbouring Lucknow by

Richard Johnson, Head Assistant to the

British Resident, during 1780 to 1782. Some

closely resemble the works of Sita) Das who

made a set of paintings for Johnson depicting

Vedic sacrifices (Album 5)-subjects which

incidentally appear on the map of I<handesh

in Gentil's atlas. Others have much in common

with the work of Gobind Singh and Ghulam

Reza who produced a ragmala (Album 42) for

Johnson and also illustrated for him the

fables of the Ivar-i-Danish (Album 54). All these

sets are illustrated in watercolour in the same

delicate colours-grey, pink, mauve, pale

yellow and green-as those used by Gentil's

artists. It is dear that adjustments to European

tastes and interests had in fact begun at

Faizabad at least ten years before Johnson

went to Lucknow. It is also significant that in

Gentil's atlas, subjects which were later to

become the stock-in-trade of 'Company'

painters were already present in miniature

form. Hitherto the early date of this phenomenon in northern India has not been fully

recognised, but as proof of it there is no more

vivid testimony than Gentil's private copy of

the illustrated atlas in the Library's collection.

Tilly Kettle was also working in Faizabad in

1772, and his work greatly influenced the Indian

artists painting for Europeans. Gentil acquired the

original of a portrait of Shuja painted by Tilly when

the copy he had had made was appropriated by the

Nawab, and presented it to the king when he got

back to France. It is now in the Versailles Museum.

Another painting of the Nawab and his ten sons,

also presented by Gentil, is in the Musee Guimet.

This was a copy by Nevasi Lal, one of the artists

employed by Gentil, of a painting by Kettle. ·Other

Europeans who are known to have been in Faizabad

at the time include the Frenchman Claude Martin

and the Swiss Antoine Potier, both of whom took a

keen interest in Indian painting and literature. According to a note by his son, Gentil employed three

Indian artists for a period of ten years to supply him

with the illustrations needed for the albums, and to

make copies of Indian miniatures for Gentil to carry

back to France. Two of these artists are known from

the title of the 'Recueil', Nevasi Lal and Mohan Singh;

the third remains anonymous as so many Indian

artists were.

Gentil's influence on later work

We have already seen that Gentil's role in the

development of a new style of painting at Faizabad

went unrecognised by scholars in Britain until the

atlas and the 'Recueil' were acquired by the India

Office Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum

respectively a few years ago. In the geographical

field also, his pioneering work remained hidden in

the King's library, and in his own home. In the first

edition of his Memoir of a Map of Hindoostan, or the

Mogul's Empire in 1783, James Rennell, by this time

back in England and g~tting his maps engraved,

mentioned Gentil only once, quoting a longitude

reading he had made at Pondicherry in 1769. It is

probable that Rennell did not know of Gen til' s atlas,

or his translation of the geographical part of the

A'in-i Akbari, and anyway he claimed not to have

placed much reliance on the latter himself: 'From

such kind of materials, nothing very accurate can be

expected; and therefore I have n~ver had recourse to

them but in a very few cases, where every other

species of information has failed.' (p. 47) Yet he

retained the political division of India according to

the Mughal subas for his description of the country,

and relied on d 'Anville for many areas where he had

been unable to obtain more recent information. The

hostility between England and France was also an

inhibiting factor in the free exchange of knowledge.

The war between the two countries did not,

however, prevent those with liberal minds from

exchanging views. Robert Orme was in correspondence with the Indian scholar in Paris, Anquetil du

Perron. In a letter dated 11 May 1784 he wrote:

What has passed between us concerning that

respectable & lamented man M. D' Anville

is applicable to the Indian Geographers of

England. Rennel [sic] says I ought to confine

myself to the higher sphere of history. I see him

peevish about me in his last publication, concerning his map of Indostan, which is·very

neat, too small, and would have admitted of

another order of [ . ? . ] later than the time of

Arbas - he appears 'to have been amazed

at the Map of the Deccan I made for the fragments, he nor my friend Dalrymple had

never read your Joumies in India, nor knew

of the journey from Golcondah to Theleabass,

or Allahabad, which is a curious manuscript

given by my friend

therefore unique. F

not given your map

and shall let them ·

published, as I appr

be prepared before

and it is right that th1

time it costs to exam

as it may easily jud~

compose it. (Bib. N<

p.176)

A few months later, on lE

writing in similar vein:

At the time he [Re

general map of India

and had spent £100

The map I give with tl

of my general inten(

your route the most '

them traced on large

reputation is very I

apply themselves to t

affairs as they stand n•

patrons. (ibid., p.187

Rennell lived until 1830

powerful influence on all m•

veying and geography of h

the trigonometrical survey:

stating that route surveys

were quite adequate and the

tion for the expense of more

techniques. After the pub!

Perron's Description geograph

by Johann Bernoulli in 17~

learnt of Gentil's work, sin

quoted him repeatedly. He

essays contributed by Gent

Sikhs and the jats, in which h

the place-names supplied b

Rennell's map.

Since Gentil's maps anc

in manuscript form, they nev

they warranted. In the Pre

Mughal Empire, lrfan Habib

Elliot and Beames in the mic

to prepare maps of north Im

ministrative divisions of Akl

in the A'in-i Akbari, since, as l

reads his [Abu-I Fazl's] "Acei

vinces" must surely be tempt

on maps.' He did not know

had been answered in Faiz•

duced such splendid, even if

j lavish diffusion of money in every

:, artisans and scholars flocked hither

lgal, Gujrat, Malwah, Haidera-bad,

Lahaur, Peshawar, Kabul,

ltan.' This is how Muhammad Faiz

d the court of Shuja-ud-daula at

plendour of the Mughal court at

vas gone by the middle of the 18th

ti itself was in ruins after the devasthe Rohillas. So Shuja-ud-daula

1g patron of the arts in north India.

irrated it, Shuja-ud-daula was the

::m of Sa'adat Khan, Governor of

' of Oudh under the Emperor Far' s father Safdarjang was Sa'adat

md son-in-law, and succeeded to

made vazir in 1747 when Ahmed

throne, but the jealousy of Ghazi1e him to retire to his estates where

;huja succeeded to the title of Mir

uba of Arig, Oudh and Allahabad.

may differ, but this is how Gentil

td.

·r the treaty with the British at

moved his capital from Lucknow

;et about building a city worthy of

death, however, his son returned

~aizabad was left to decay after its

ndour. There is no record of paint1 the first half of the century, and

artists there were was probably

from the imperial style at Delhi.

' of 115 paintings in the Victoria

n (1.5. 48-1956) that was presented

;huja-ud-daula in about 1765-67,

til began his employment there.

1ence is apparent in the paintings

portraits and flowers, and no

nted them. Yet within five years

• acquire series of albums full of

•le he wanted. Mildred Archer, in

le Gentil atlas in the IOL Report

~scribed the artistic milieu at

e when Centil was Jiving in

Jdh was culturally in a flourishing

the troubles in Delhi during 1759

.y Delhi families including writers

ad moved there. This was a great

·du poetry when Mirza Muhammda, Mian Hazrat and Ashraf

ere writing. Painting also was

The Nawab and nobility were

artists and many portraits and

; were being produced in a dis-

tinctive style. Elongated figures in white

jamas were shown sitting on terraces or walking

in gardens with ladies as gay as the parterres

of flowers through which they stroJled.

Faizabad was an ideal centre for Gentil who

took a lively interest in Indian life and culture.

Dr Archer goes on to describe the paintings that

surround the maps in Gentil's atlas:

Stylistically they are very close to other

drawings in the Library's collection-those

commissioned in neighbouring Lucknow by

Richard Johnson, Head Assistant to the

British Resident, during 1780 to 1782. Some

closely resemble the works of Sita] Das who

made a set of paintings for Johnson depicting

Vedic sacrifices (Album 5)-subjects which

incidentally appear on the map of Khandesh

in Gentil' s atlas. Others have much in common

with the work of Gobind Singh and Ghulam

Reza who produced a ragma/a (Album 42) for

Johnson and also ilJustrated for him the

fables of the Iyar-i-Danish (Album 54). All these

sets are illustrated in watercolour in the same

delicate colours-grey, pink, mauve, pale

yellow and green-as those used by Gentil's

artists. It is clear that adjustments to European

tastes and interests had in fact begun at

Faizabad at least ten years before Johnson

went to Lucknow. It is also significant that in

GentiJ's atlas, subjects which were later to

become the stock-in-trade of 'Company'

painters were already present in miniature

form. Hitherto the early date of this phenomenon in northern India has not been fulJy

recognised, but as proof of it there is no more

vivid testimony than Gentil's private copy of

the illustrated atlas in the Library's collection.

Tilly Kettle was also working in Faizabad in

1772, and his work greatly influenced the Indian

artists painting for Europeans. Gentil acquired the

original of a portrait of Shuja painted by Tilly when

the copy he had had made was appropriated by the

Nawab, and presented it to the king when he got

back to France. It is now in the Versailles Museum.

Another painting of the Nawab and his ten sons,

also presented by Gentil, is in the'Musee Guimet.

This was a copy by Nevasi Lal, one of the artists

employed by Gentil, of a painting by Kettle. ·Other

Europeans who are known to have been in Faizabad

at the time include the Frenchman Claude Martin

and the Swiss Antoine Potier, both of whom took a

keen interest in Indian painting and literature. According to a note by his son, Gentil employed three

Indian artists for a period of ten years to supply him

with the illustrations needed for the albums, and to

make copies of Indian miniatures for Gentil to carry

back to France. Two of these artists are known from

the title of the 'Rerueil', Nevasi Lal and Mohan Singh;

the third remains anonymous as so many Indian

artists were.

Gentil's influence on later work

We have already seen that Gentil's role in the

development of a new style of painting at Faizabad

went unrecognised by scholars in Britain until the

atlas and the 'Recueil' were acquired by the India

Office Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum

respectively a few years ago. In the geographical

field also, his pioneering work remained hidden in

the King's library, and in his own home. In the first

edition of his Memoir of a Map of Hindoostan, or the

Mogul's Empire in 1783, James Rennell, by this time

back in England and g~tting his maps engraved,

mentioned Gentil only once, quoting a longitude

reading he had made at Pondicherry in 1769. It is

probable that Rennell did not know of Gentil's atlas,

or his translation of the geographical part of the

A'in-i Akbari, and anyway he claimed not to have

placed much' reliance on the latter himself: 'From

such kind of materials, nothing very accurate can be

expected; and therefore I have n~ver had recourse to

them but in a very few cases, where every other

species of information has failed.' (p. 47) Yet he

retained the political division of India according to

the Mughal subas for his description of the country,

and reJied on d' Anville for many areas where he had

been unable to obtain more recent information. The

hostility between England and France was also an

inhibiting factor in the free exchange of knowledge.

The war between the two countries did not,

however, prevent those with liberal minds from

exchanging views. Robert Orme was in correspondence with the Indian scholar in Paris, Anquetil du

Perron. In a letter dated 11 May 1784 he wrote:

What has passed between us concerning that

respectable & lamented man M. D' Anville

is applicable to the Indian Geographers of

England. Rennet [sic] says I ought to confine

myself to the higher sphere of history. I sec him

peevish about me in his last publication, concerning his map of lndostan, which is ·very

neat, too small, and would have admitted of

another order of [ . ? . ] later than the time of

Arbas - he appears 10 have been amazed

at the Map of the Deccan I made for the fragments, he nor my friend Dalrymple had

never read your journies in India, nor knew

of the journey from Golcondah to Theleabass,