Canterbury Tales – Wife of Bath

advertisement

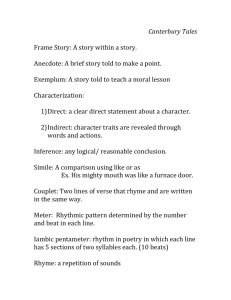

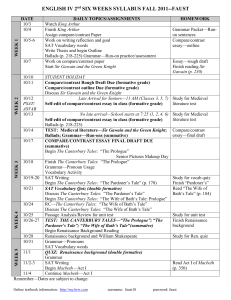

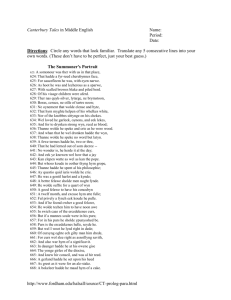

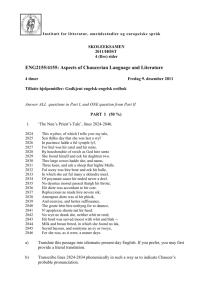

Study Guide: Canterbury Tales – Wife of Bath (Kiley Dhatt) Title: The Canterbury Tales – “The Wife of Bath’s Prologue” and “The Wife of Bath’s Tale” Author (if known): Geoffrey Chaucer Publication Date: 1478 (1st ed. William Caxton; written c. 1340-70) Form/genre: Some stories in prose and most in verse; verse is rhyming couplets of 10 syllable (decasyllable) lines, with iambic pentameter-like alternating unstressed and stressed syllables. Genre was a well-known form at the time: a collection of stories anchored in a frame narrative, although it is an amazing compendium of genres: the romances or courtly tales of love and adventure of high-class men and women; the fabliaux, or comic tales often involving middleclass folk engaged in raunchy misconduct; saints’ legends; moral exempla; religious tales and sermons; confessorial narratives; tragedies; allegories; meditations; and even parodies. (adapted from Introduction to The Canterbury Tales ed. Peter G. Beidler 2006). Short context (historically speaking): Thomas Becket is the “holy, blissful martyr” to whose tomb in Canterbury the pilgrims are journeying. Henry II named him Archbishop in 1161, with the motive of keeping the powerful medieval Christian church under his control, but Becket found his loyalties in the pope and Christian teachings. By the time of Chaucer’s writing, St. Thomas’s Canterbury was the most frequent pilgrim destination in England. The text was written around the end of the Hundred Years’ War, a series of diplomatic and military conflicts between England and France that consumed the energies and funds of both nations for around a century as both strove to carve out and maintain their holding and their identities as nations. It was also written in the wake of the English Rising, the first major revolt of the commoners against a member of the British royalty, initiated by a per-capita tax on the English people by their king in 1381 (the 3rd such tax in 4 years). Support for the revolt came not just from farmworkers but also from England’s growing class of businessmen, townspeople, artisans, and even clerics. During the rebellion, King Richard II claimed to concede to all of their demands in order to disburse the angry mobs, but later reneged on his promises, claiming he made them under duress. Lastly, although the medieval Christian church was pre-Protestant Reformation, the Western Schism split the Catholic church from 1378-1418, when the French cardinals were dissatisfied with the newly appointed pope in Rome, Urban VI, and boldly named their own rival pope in Avignon. The English tended to support the Italian pope, but the fact was that for the last quarter of the 14th century, when Chaucer was in his most productive mode, there were two Catholic popes, each proclaiming himself o be the rightly appointed anointed head of Christianity, creating confusion and doubt among ordinary Christians. Content (brief overview of the entire narrative): Wife of Bath: There is no head-link to this narrative; prologue is unconnected to previous tales, and host never calls on Alisoun to speak up. The prologue can be thought of in two parts: 1) expository mode: Alisoun explains why she prefers virginity to chastity and why she prefers multiple or successive marriages to a state of widowhood, which ends with the interruption of the Pardoner, who requests that she teach young men like him about her marital practices. 2) autobiographical mode: Alisoun tells about her own five marriages in chronological order, three to rich old men and then two to more desirable but more impoverished younger men, which ends with an interruptions by the Friar and Summoner. The Host then commands the two to “let the woman tell her tale.” Told in the narrative mode, the WoB’s tale itself is a romance about one of King Arthur’s young knights who rapes a woman. To pay for his crime the knight is sent by Arthur’s queen on a year-long quest to discover what women most desire. At the center of the tale is an enigmatic old woman who teaches several lessons to the impulsive young knight and in the end rewards him for learning those lessons. Themes: The Wife of Bath sees marriage as a tool to be used to a woman’s advantage. She observes that she had no motivation to please her old, rich husbands, since they already loved her well, and she didn’t stand to gain profit or pleasure. She believes husbands owe their wives a “debt,” both of general and sexual/reproductive service. The morals of the tale itself are that women’s greatest desire is to have dominion over men, and that “nobility” or virtuousness is performed, rather than inherited. Keywords/Tags: marriage, maidenhood, virginity, Arthurian romances, Christianity, religious imperatives, sexual desire, femininity, gender performance Key Passages: (Old English on left; translation on right) Deceite, weping, spinning God hath yive To women kindely, whyl they may live. And thus of o thing I avaunte me, Atte end I hadde the better in ech degree, By sleighte, or force, or by som maner thing, As by continuel murmur or grucching; Namely abedde hadden they meschaunce, There wold I chide and do hem no pleaunce; I would no lenger in the bed abyde, If I felte his arm over my syde, Til he had maad his raunson unto me; Than wolde I suffer him to do his nycetee. And therefore every man this tale I telle, Winne whoso may, for al is for to selle: With empty hand men may none haukes lure; For winning wolde I al his lust endure, And make me a feyned appetyt; And yet in bacon hadde I never delyt— That made me that ever I wolde hem chyde. For thogh the pope had seten hem bisyde, I wolde nat spare hem at hir owene bord; For by my trouthe, I quitte hem word for word. As help me verray God omnipotent, Thogh I right now sholde make my testament, I ne owe hem nat a word that it nis quit. I broghte it so aboute by my wit That they moste yeve it up, as for the beste; Or ells hadde we never been in rest. For thogh he loked as a wood leoun, Yet sholde he faille of his conclusioun. God has given women by nature deceit, weeping, and spinning, as long as they live. And thus I can boast of one thing: in the end I got the better of them in every case, by trick, or force, or by some kind of method, such as continual complaining or whining; in particular, they had misfortune in bed, where I would chide and given them no pleasure; I would no longer stay in the bed if I felt my husband’s arm over my side until he had paid his ransom to me; then I’d allow him to do his bit of business. Therefore I tell this moral to everyone— profit whoever may, for all is for sale: you cannot lure a hawk with an empty hand; for profit I would endure all his lust, and pretend an appetite myself; and yet I never had a taste for aged meat— that’s what made me scold them all the time. For even if the pope had sat beside them, I wouldn’t spare them at their own board; I swear I requited them word for word. So help me almighty God, even if I were to make my testament right now, I don’t owe them a word which has not been repaid. I brought it about by my wit that they had to give up, as the best thing to do, or else we would never have been at rest. For though he might look like a raging lion, yet he would fail to gain his point. “Heer may ye see wel how that genterye Is nat annexed to possessioun, Sith folk ne doon hir operacioun Alwey, as dooth the fyr, lo, in his kinde, For God it woot, men may wel often finde A lords sone do shame and vileiyne; And he that wol han prys of his gentry For he was boren of a gentil hous, And hadde hise eldres noble and vertuous, And nil himselven do no gentil dedis, Ne folwe his gentil auncesre that deed is, He his nat gentil, be he duk or erl; For vileyns, sinful dedes make a cherl. For gentillesse nis but renomee Of thyne auncestres, for hir heigh bountee, Which is a strange thing to thy persone. Thy gentillesse cometh fro God alone; Than comth our verray gentillesse of grace, It was no thing biquethe us with our place.” “By this you can easily see that nobility is not tied to possessions, since people do not perform their function without variation as does the fire, according to its nature. For, God knows, men may very often find a lord’s son committing shameful and vile deeds; and he who wishes to have credit for his nobility because he was born of a noble house, and because his elders were noble and virtuous, but will not himself do any noble deeds or follow the example of his late noble ancestor, he is not noble, be he duke or earl; for villainous, sinful deeds make him a churl. This kind of nobility is only the renown of your ancestors, earned by their great goodness, which is a thing apart from yourself. Your nobility comes from God alone; then our true nobility comes of grace, it was in no way bequeathed to us with our station in life.”