as a PDF

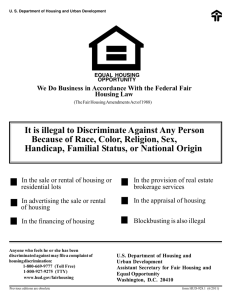

advertisement