1901 UP FROM SLAVERY Booker T. Washington

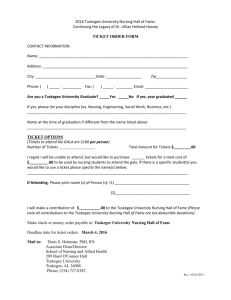

advertisement