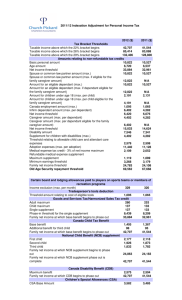

Evaluation of the National Child Benefit Initiative: Synthesis Report

advertisement