THE TEXAS SCHOOL FINANCE LITIGATION SAGA

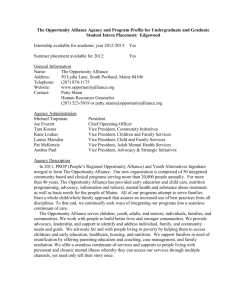

advertisement