The Goods Market and the Aggregate Expenditures Model

advertisement

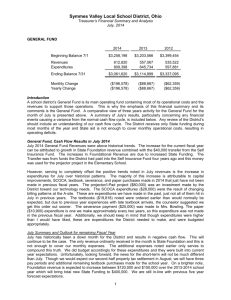

The Historical Development of Modern Macroeconomics The Goods Market and the Aggregate Expenditures Model n The Great Depression of the 1930s led to the development of macroeconomics and aggregate demand tools to deal with recessions. n During the Depression, output fell by 30 percent and unemployment rose to 25 percent. Chapter 8 2 The Historical Development of Modern Macroeconomics n Classical Economists Keynes is the author of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, which provided the new framework for macroeconomic policy. n The Classical economists' approach was laissez-faire (leave the market alone). n They believed the market was self-adjusting. n They concentrated on the long run and largely ignored the short run. 3 Classical Economics 4 Classical Economics n They used microeconomic supply and demand arguments to explain the Great Depression. n Classical economists opposed deficit spending, arguing that the money to create jobs had to be borrowed. n Their solution to the high unemployment was to eliminate labour unions and government policies that kept wages too high. n This money would have financed private economic activity and jobs, so everything would cancel out (called crowding out). 5 6 The Historical Development of Modern Macroeconomics The Essence of Keynesian Economics n n Before the Depression, the prominent ideology was laissez-faire -- keep the government out of the economy. n After the Depression, most people believed government should have a role in regulating the economy. Keynes thought that the economy could get stuck in a rut as wages and price level adjusted to sudden decreases in expenditures. 7 The Essence of Keynesian Economics n 8 Equilibrium Income Fluctuates According to Keynes: a decrease in spending ⇒ job layoffs ⇒ fall in consumer demand ⇒ firms decrease production ⇒ more job layoffs ⇒ further fall in consumer demand, and so forth n Income is not fixed at the economy's long-run potential income – it fluctuates. n For Keynes there was a difference between equilibrium income and potential income. 9 Equilibrium Income Fluctuates Equilibrium Income Fluctuates n n 10 Equilibrium income – the level toward which the economy gravitates in the short run because of the cumulative cycles of declining or increasing production. Potential income – the level of income that the economy technically is capable of producing without generating accelerating inflation. 11 n Keynes felt that at certain times the economy needed help to reach its potential income. n He believed that market forces would not work fast enough and would not be strong enough to get the economy out of a recession. 12 The Paradox of Thrift n n The Paradox of Thrift Incomes would fall as people lost their jobs causing both consumption and saving to fall as well. n Paradox of thrift – an increase in savings can lead to a decrease in expenditures, decreasing output and causing a recession. The economy would reach a new low-level equilibrium which could be at an almost permanent recession. 13 The Aggregate Expenditures Model 14 The Aggregate Expenditures Model n Using a few simplifying assumptions, economists can construct a model of the economy. n The AE model assumes that the price level is fixed, and explores how an initial shift in expenditures changes equilibrium output. n The Aggregate Expenditures (AE) Model looks at how real income is determined in an economy. n The AE model quantifies the effect of changes in aggregate expenditures on aggregate output. 15 Aggregate Production n Aggregate production –the total amount of goods and services produced in every industry in an economy. n Production creates an equal amount of income. n Thus, actual production and actual income are always equal. 16 Aggregate Production 17 n Graphically, aggregate production in the AE model is represented by a 45° line through the origin n At all points on this Aggregate Production Curve, income equals production. 18 The Aggregate Production Curve Aggregate Expenditures n Real production Aggregate production (production = income) C A $4,000 Aggregate expenditures – the total amount of spending on final goods and services in the economy: q q q 0 q Potential income 45º $4,000 Real income Consumption – spending by households. Investment – spending by business. Spending by government. Net foreign spending on Canadian goods – the difference between Canadian exports and imports. 19 Autonomous and Induced Expenditures n n Autonomous and Induced Expenditures Autonomous expenditures are expenditures that are independent of income. q 20 n Autonomous expenditures is the level of expenditures that would exist at zero income and they remain constant at all levels of income. n Induced expenditures are those that change as income changes, but they rise by less than the change in income. Autonomous expenditures change because something other than income changes. Induced expenditures – expenditures that change as income changes. 21 Expenditures Function 22 The Expenditures Function n n The relationship between expenditures and income can be expressed more concisely as an expenditures function. n An expenditures function is a representation of the relationship between aggregate expenditures and income. The relationship between aggregate expenditures and income can be expressed mathematically: AE = AEo + mpcY AE = aggregate expenditures AE o = autonomous expenditures mpc = marginal propensity to consume Y = income 23 24 The Marginal Propensity to Consume The Marginal Propensity to Consume n Marginal propensity to consume (mpc) – the change in consumption that occurs with a change in income. n The mpc is between 0 and 1 because individuals tend to save a portion of an increase in income. n The mpc is the fraction spent from an additional dollar of income or mpc is the ratio of a change in consumption (∆ C) to a change in income (∆ Y). mpc = change in consumptio n ∆C = change in income ∆Y 25 Graphing the Expenditures Function n Graphing the Expenditures Function The graphical representation of the expenditures function is called the aggregate expenditures curve. Aggregate production AE = 1,000 + 0.8Y $12,200 Real expenditures (AE) n 26 The slope of the expenditures function tells us how much expenditures change with a particular change in income. 10,000 ∆ AE = 2,000 8,000 ∆ Y = 2,500 ∆AE 2,000 slope = = ∆Y 2,500 ∆AE mpc = = 0.8 ∆Y 6,000 5,000 4,000 2,000 1,000 0 45º $5,000 $8,750 $11,250$14,000 Real income 27 Shifts in the Expenditures Function Shifts in the Expenditures Function n The aggregate expenditure curve shifts when autonomous C, I, G, or (X – IM) change. n Autonomous Consumption expenditures respond to changes in factors other than a change in real income, for example: n n n 28 n Autonomous Investment is the most volatile component of GDP. n It responds to changes in: n n n interest rates household wealth expectations of future conditions n 29 interest rates capital goods prices consumer demand conditions expectations regarding future economic conditions 30 Determining the Equilibrium Level of Aggregate Income Shifts in the Expenditures Function n n Autonomous exports and imports depend on foreign and domestic incomes and relative prices. Autonomous Government expenditures may also change as policies change. n At equilibrium, planned expenditures must equal production. n Graphically, it is the income level at which AE equals AP. 31 Solving for Equilibrium Graphically Real expenditures (AE) Solving for Equilibrium Algebraically Aggregate production $14,000 Aggregate expenditures AE = 1,000 + 0.8Y 12,200 10,000 32 n In equilibrium, Y = AE. n Substituting in for aggregate expenditures, we have Y = AE0 + mpcY 8,000 E 5,000 2,600 1,000 0 AE0 = $1,000 45° $2,000 $5,000 $10,000 $14,000 Real income 33 Solving for Equilibrium Algebraically n 34 The Multiplier Equation Now solve for equilibrium income: n Y – mpcY = AE 0 The multiplier equation tells us that income equals the multiplier times autonomous expenditures. Y = Multiplier X Autonomous expenditures Y (1 – mpc) = AE 0 Y = [ 1/ (1 – mpc) ] * AE 0 35 36 The Multiplier Equation n The multiplier process amplifies changes in autonomous expenditures. n What forces are operating to ensure that the income level we determined is actually the equilibrium income level? The Multiplier Process n When aggregate production do not equal aggregate expenditures: Businesses change production levels, which changes income, which changes expenditures, which changes production, which changes income, which changes . . . etc. n 37 The Multiplier Process n The Multiplier Process C, I, G, (X – IM) The process ends when aggregate production equals aggregate expenditures. A1 Aggregate production Aggregate A2 expenditures AE = 1,000 + 0.8Y $14,000 $13,200 Real expenditures (AE) n 38 Firms are selling all they produce, so they have no reason to change their production levels. 10,000 C B1 6,000 B2 2,000 45° 0 $2,000 $5,000 $10,000 $14,000 Real income 39 The Circular Flow Model and the Multiplier Process n The circular flow model provides the intuition behind the multiplier process. n The flow of expenditures equals the flow of income. 40 The Circular Flow Model and the Multiplier Process 41 n Expenditures are injections into the circular flow. n The mpc measures the percentage of expenditures that get injected back into the economy each round of the circular flow. n But there are withdrawals. 42 The Circular Flow Model and the Multiplier Process n The Circular Flow Model and the Multiplier Process n Economists use the term the marginal propensity of save (mps) to represent the percentage of income flow that is withdrawn from the economy for each round of the circular flow. By definition: mpc + mps = 1 n Alternatively expressed: mps = 1 - mpc multiplier = 1/mps 43 The Circular Flow Model and the Multiplier Process The AE Model in Action n Aggregate income Households 44 The AE model illustrates how a change in autonomous expenditures changes the equilibrium level of income. Firms Aggregate expenditures 45 The Multiplier Model in Action n Autonomous expenditures are determined outside the model and are not affected by changes in income. n When autonomous expenditures shift, the multiplier process is called into play. 46 The Steps of the Multiplier Process 47 n The income adjustment process is directly related to the multiplier. n Any initial shock (a change in autonomous AE) is multiplied in the adjustment process. 48 Shifts in the Aggregate Expenditure Curve The Steps of the Multiplier Process n The multiplier process repeats and repeats until a new equilibrium level is finally reached. Aggregate production C, I $4,200 E0 4,160 20 E0 AE0 = 832 + .8Y AE1 = 812 + .8Y $20 12.8 4,100 4,060 20 832 812 0 D AEA = $20 $16 D AEA = $16 D AEA = $12.8 E1 E1 $100 $4,060 $4,160 Real income 100 49 First Five Steps of Four Multipliers mpc = 0.5 50 First Five Steps of Four Multipliers mpc = 0.75 100 mpc = 0.8 100 100 100 80 75 81 72.9 65.61 51.2 42.19 31.64 25 90 64 56.25 50 mpc = 0.9 40.96 12.5 6.25 Multiplier = 1/(1-0.5) = 2 Multiplier = 1/(1-0.75) = 4 Multiplier = 1/(1-0.8) = 5 Multiplier = 1/(1-0.9) = 10 51 The Effect of Shifts in Aggregate Expenditures Examples of the Effect of Shifts in Aggregate Expenditures n n There are many reasons for shifts in autonomous expenditures: q q q q 52 An understanding of these shifts can be enhanced by tying them to the formula: AE = C + I + G + X - IM Natural disasters. Changes in investment caused by technological developments. Shifts in government expenditures. Large changes in the exchange rate. 53 54 Upward Shift of AE Real expenditures $4,210 Downward Shift of AE ∆Y = 4,090 1,052.5 1 [∆AE 0] 1 - 0.75 1,412 1,382 $120 $4,090 $4,210 Aggregate production AE0 30 AE1 ∆Y = 4,062 = 4 [∆AE 0 ] = 120 30 1,022.5 0 Real expenditures $4,152 Aggregate production AE 30 1 AE0 Real income 0 1 [∆AE 0] 1 - 0.66 = 3 [∆AE 0 ] = 90 30 $90 $4,062 $4,152 Real income 55 Canada in 2000 Real World Examples n Canada in 2000. n Japan in the 1990s. n The 1930s depression. 56 n Consumer confidence rose substantially causing autonomous consumption expenditures to increase more than economists had predicted. n While economists had expected the economy to grow slowly, it boomed. 57 Japan in the 1990s n The 1930s Depression Aggregate income and production fell during the 1990s. q q q 58 A dramatic rise in the yen cut Japanese exports. Autonomous consumption decreased as consumers’ confidence fell Suppliers responded by laying off workers and cutting production. 59 n The 1929 stock market crash, which continued into 1930, threw the financial markets into chaos. n This resulted in a downward shift of the AE curve as wealth decreased. 60 The 1930s Depression The 1930s Depression n Frightened business people decreased investment and laid off workers. n Frightened consumers decreased autonomous consumption and increased savings, thereby increasing withdrawals from the system. n n Business people responded by decreasing output, which decreased income, starting a downward cycle, thereby confirming the fears of the businesspeople. n The process continued until the economy settled at a low-level equilibrium, far below the potential level of income. Governments cut spending to balance their budgets, as tax revenue declined. 61 The 1930s Depression 62 AE Model Is Not a Complete Model n The process caused the paradox of thrift, whereby individuals attempting to save more, spent less, and caused income to decrease. n They ended up saving not more, but less. n The AE model determines income given autonomous expenditures. n These autonomous expenditures, however, are determined by economic variables which are not in our simple model. 63 Model of Aggregate Demand AE Model Is Not a Complete Model n The AE model uses aggregate expenditures to determine equilibrium income. n It does not explain production. n 64 It assumes firms can supply the output demanded. 65 n Shifts may be simultaneous shifts in supply and demand that do not necessarily reflect suppliers responding to changes in demand. n Expansion of this line of thought has led to the real business cycle theory of the economy. 66 Model of Aggregate Demand n Prices are Fixed Real business cycle theory of the economy – changes in aggregate supply are the principle way for real income to change. n The multiplier model assumes that the price level is fixed. n In reality, the price level can change in response to changes in aggregate demand. 67 Does Not Include Expectations n Forward-Looking Expectations Complicate the Adjustment Process People's forward-looking expectations make the adjustment process much more complicated. n Most people, however, act upon their expectations of the future. n Business people may not automatically cut back production and lay-off workers if they think a fall in sales is temporary. 68 n Rational expectations model – captures the effect expectations have on individuals’ behaviour. n Expectations can be self-fulfilling. 69 Consumption Behaviour 70 Expanded AE Model n People may base their spending on lifetime income, not yearly income. n We can increase the power of our AE model by adding more detail. n Permanent income hypothesis -- the hypothesis that expenditures are determined by permanent or lifetime income. n For example, adding taxes to the model q q q 71 Changes consumption expenditures. Introduces government budget deficits and surpluses. Changes the multiplier. 72 Expanded AE Model n Expanded AE Model Adding income-induced imports q n Changes import spending. The marginal propensity to import (mpi) gives the increase in import spending from an additional $1 of disposable income. q q Changes net exports, n q Disposable = after-tax and introduces trade surpluses and deficits. n Mpi lies between 0 and 1 Changes the multiplier. 73 The Goods Market and the Aggregate Expenditures Model End of Chapter 8 74