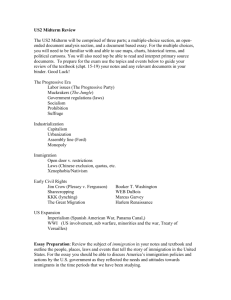

Kevin R. Johnson Introduction - Law web site

advertisement