Philippines ADB - Global Environment Facility

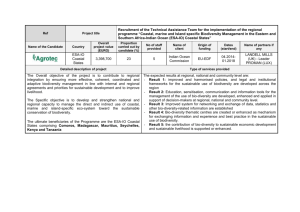

advertisement