Knock, Knock. Who's There? Lesson 5

advertisement

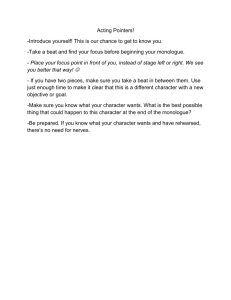

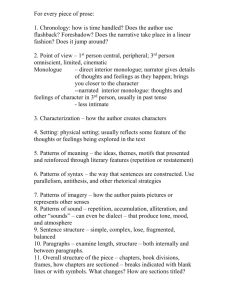

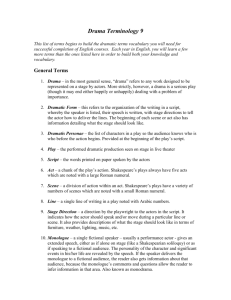

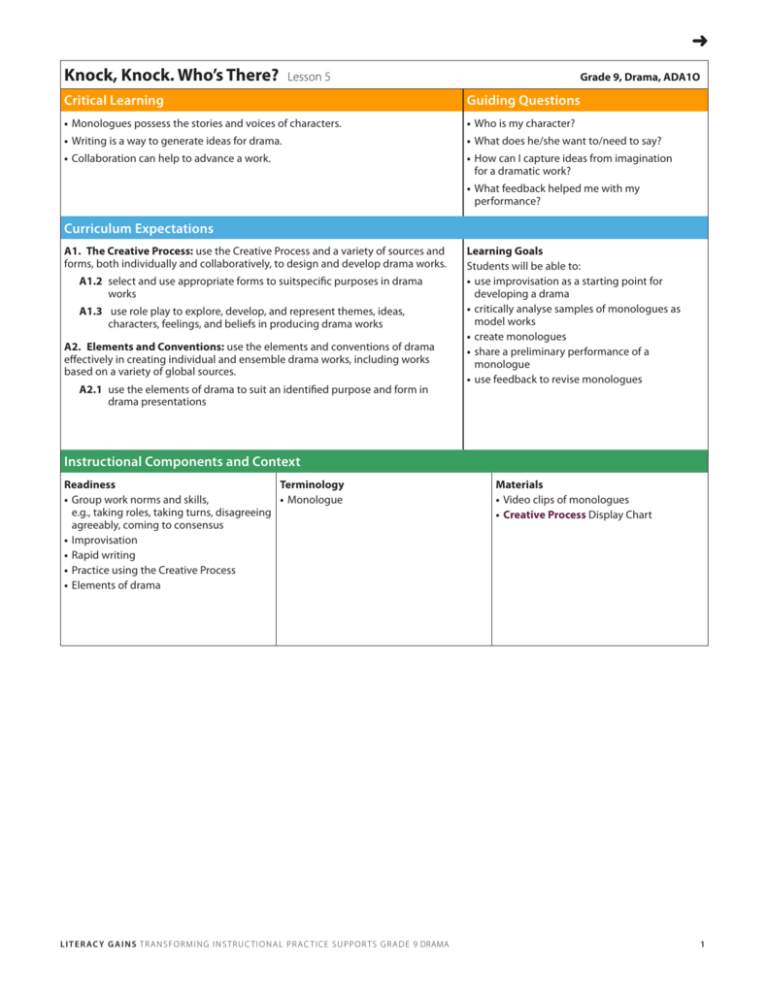

➜ Knock, Knock. Who’s There? Lesson 5 Grade 9, Drama, ADA1O Critical Learning Guiding Questions •• Monologues possess the stories and voices of characters. •• Who is my character? •• Writing is a way to generate ideas for drama. •• What does he/she want to/need to say? •• Collaboration can help to advance a work. •• How can I capture ideas from imagination• for a dramatic work? •• What feedback helped me with my performance? Curriculum Expectations A1. The Creative Process: use the Creative Process and a variety of sources and forms, both individually and collaboratively, to design and develop drama works. A1.2 s elect and use appropriate forms to suitspecific purposes in drama works A1.3 use role play to explore, develop, and represent themes, ideas, characters, feelings, and beliefs in producing drama works A2. Elements and Conventions: use the elements and conventions of drama effectively in creating individual and ensemble drama works, including works based on a variety of global sources. A2.1 u se the elements of drama to suit an identified purpose and form in drama presentations Learning Goals Students will be able to: •• use improvisation as a starting point for developing a drama •• critically analyse samples of monologues as model works •• create monologues •• share a preliminary performance of a monologue •• use feedback to revise monologues Instructional Components and Context Readiness Terminology •• Group work norms and skills, • •• Monologue e.g., taking roles, taking turns, disagreeing agreeably, coming to consensus •• Improvisation •• Rapid writing •• Practice using the Creative Process •• Elements of drama L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA Materials •• Video clips of monologues •• Creative Process Display Chart 1 ➜➜ Knock, Knock. Who’s There? Lesson 5 Grade 9, Drama, ADA1O Minds On Whole Class/Individual ➔ Using improvisation to explore ideas Explain that they will use improvisation to develop ideas. Ask students to imagine they are knocking at a door, and provide them with the lines: “It’s me. Are you in there? I’ve got something I want to say…” Students develop a character, creating a line or two to follow the opening, and decide on delivery and improvise e.g., banging on the door and yelling. They share their improvisation with the class. Debrief by asking each student to comment on the choices they made. Ask some students to change the delivery, and as a class, discuss the impact on the meaning. Extend the discussion by posing the question: “How did the improvisation help you explore a situation and character?” Pause and Ponder • Monitor students as they prepare for their improvisation. Assess their readiness to share their improvisation for the class. Pose questions related to the character and situation, as necessary. Action! Whole Class ➔ Using the critical analysis process Post the critical analysis process organizer and critical analysis questions for the monologue (e.g., on an anchor chart) for students to refer to. Provide background information on the monologues, e.g., title of the work, name of playwright and his/her background, the character and situation. Post the creative process. Help students to identify where they are in the process. Show a clip from the monologue. Model the critical analysis process by using critical analysis questions for the monologue. Students view a video clip of a monologue, using the Critical Analysis Process and make notes for one or more of the questions for each of the stages. Students view a second monologue. Using mix and mingle students share responses with peers. Guide the sharing by calling out the stage of the process students should discuss for each pairing. Debrief by reviewing the elements of drama, i.e., role/character, time and place, tension, relationship, focus and emphasis. Discuss and note on a T-chart how these elements were used in the two monologues. Assess students understanding of the critical analysis process as they discuss questions in the mix and mingle. Whole Class ➔ Co-constructing success criteria Review and discuss the learning goals. Co-construct success criteria for monologue writing and performance, including clearly defined relationships, character intention, and motivation. Record these on an anchor chart. In a Think-Pair-Share, students describe what success looks for each of the criteria. Debrief by inviting responses and note any details as examples on the success criteria anchor chart. Individual ➔ Writing monologues Explain that they will write monologues imagining their character is at a door talking to someone on the other side who does not respond back. Point out that the door metaphorically represents a barrier or obstacle. Students use the Minds On activity, the monologues they viewed, or some other inspiration as a starting point. They use rapid writing and a monologue planning template as tools for generating ideas for writing. Students select which tool they will begin with, and are flexible, e.g., go back and forth between the tools as they generate ideas. Then, they complete drafts of their monologue. Whole Class/Small groups/Individual ➔ Working on monologues Review success criteria, and add any additional criteria based on students’ experience. Prompt students to be as specific as they can when describing what success looks like. Conference with students as they create their monologues. Form guided writing groups, as necessary, for students who need additional support. Each student reads their monologue draft, while the other members of the group pose questions and provide feedback using success criteria. Students record suggestions and questions related to their monologue. Once all the monologue drafts have been read in the group, each student individually considers feedback, and incorporates it as they revise their drafts. Students make decisions about any movement and gestures they will use in the performance. Small Groups ➔ Rehearsing monologues Students return to their groups. Each student, in turn, shares a preliminary performance of their monologue while other members of the group participate as audience. After each monologue, group members provide feedback on the preliminary performance. Performers note feedback in their Process Portfolio. L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA 2 ➜➜ Knock, Knock. Who’s There? Lesson 5 Consolidation Whole Class ➔ Reflecting on collaboration Students form a circle. Students share a reflection on collaboration using the sentence stem “Collaborating with my peers has helped me to…” when they receive a passed object. Individual ➔ Tracking learning Students complete their entry of their Portfolio Tracking Sheet for their Process Portfolios. They connect the “In this lesson, I discovered…” part of their entry to the learning goals for the lesson, e.g., What were your sources of inspiration for your monologue? What feedback did you receive and how might you revise your monologue based on the feedback? How does creating a monologue compared with the other works you’ve created in this unit? Students also include their feedback notes in their Process Portfolio. L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA Grade 9, Drama, ADA1O Pause and Ponder Peers provide feedback on the individual monologues to the members of their group. Use the Process Portfolio as a tool for self-assessment and reflection. Review students’ reflections in their Process Portfolios to determine whether they are on track in relation to the learning goals. 3 ➜➜ Knock, Knock. Who’s There? Lesson 5 Grade 9, Drama, ADA1O Action Critical Analysis Process The critical analysis process enables students to •• respond knowledgeably and sensitively to their own and others’ works •• make connections between their own experiences and works in the arts, between different art forms, and between • art works and the lives of people and communities around the world •• perceive and interpret how the elements of each art form contribute to meaning in works •• develop, share, and justify an informed personal point of view about works •• demonstrate awareness of and appreciation for the importance of various art forms in society •• demonstrate appreciation appropriately as audience members in formal and informal settings (e.g., peer performances • in the classroom) Students need to be guided through the stages of the critical analysis process. As they learn the stages in the process, they will • become increasingly independent in their ability to develop and express an informed response to a work. They will also become • more sophisticated in their ability to critically analyse the works they are studying or responding to. Students learn to approach • works in the arts thoughtfully by withholding judgement until they have enough information to respond in an informed manner. Taken from The Ontario Curriculum: Grades 9 and 10, The Arts, Revised 2010. Stages of the Critical Analysis Process The Critical Analysis Process includes the following aspects: •• initial reaction •• analysis and interpretation •• consideration of cultural context •• expression of aesthetic judgement •• ongoing reflection The process is intended to be used in a flexible manner, taking into account students’ prior experiences and the context in which the various art forms and works are experienced. It is important to remember that students will be engaged in reflection and interpretation throughout the process. Taken from The Ontario Curriculum: Grades 9 and 10, The Arts, Revised 2010. Critical Analysis Questions for the Monologue Initial Reaction •• What is your first impression of the monologue? •• What does this monologue remind you of? •• What emotions does this monologue evoke? •• What questions do you have? •• How is this monologue similar to and different from the -- narration and movement in Lesson 3? -- dialogues in Lesson 4? -- other dramatic works you’ve seen? Analysis and Interpretation •• What do you think the playwright is trying to say in this monologue? How is this idea communicated in the monologue, • e.g., Is it obvious in the words? Does the actor’s tone communicate something different than the words? •• Why do you think the playwright created this monologue? •• What do you feel is the playwright’s view of the world? •• What does the playwright do in the monologue to attempt to create and maintain interest for the audience? Consideration of Cultural Context •• What events in the playwright’s own life or events of the time do you think the playwright may have used as inspiration • for the work? Expression of Aesthetic Judgement •• What works in the monologue? •• What doesn’t work, and why? •• Has your point of view shifted from your initial reaction? If so, how has it changed? Reflection •• What did you find in this monologue that you might try to incorporate in your own? •• What do you think the challenges might be in creating your own monologue? L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA 4 ➜➜ Knock, Knock. Who’s There? Lesson 5 Grade 9, Drama, ADA1O Anchor Chart An anchor chart is a strategy for capturing students’ voices and thinking. Anchor charts are co-constructed. By making students’ thinking visible and public, they “anchor,” or stabilize and scaffold classroom learning. Anchor charts should be developmentally appropriate and clearly focused, accessible, and organized. Model Modeling is a component of explicit instruction that is particularly helpful for struggling learners. According to the gradual release of responsibility model for instruction, modeling is done by the teacher and students observe (I do, you watch). This is followed by shared practice (I do, you help) and guided practice (you do, peers help), and finally independent practice (you do, I help if necessary). See the Strategy Implementation Continuum for a detailed chart of this framework. Mix and Mingle This strategy provides an opportunity for constructing understanding through productive talk. It also supports community building. In this strategy, students engage in brief paired discussions about a particular topic. Students generate their own ideas to share on the topic, or the teacher provides information to read aloud to a partner. Students speak to as many partners as they can in the allotted time. As students share, they build their understanding on the topic. See Think Literacy, Subject-specific Examples, English, Grades 7-9, pp 56-59 T-Chart A T-chart graphic organizer can be used to make comparisons. A comparison T-chart is set up so the columns define the categories of the comparison, such as examples and non-examples, before and after. Depending on the task, students structure the content in each column, so that each item forms a point of comparison. That is, each column contains a structured list. Students may need explicit instruction and modeling to use the T-chart to generate ideas and how to use it to support further writing and talking opportunities about the topic. Creative Process Students are expected to learn and use the Creative Process to help them acquire and apply knowledge and skills in the arts. Creativity involves the invention and the assimilation of new thinking and its integration with existing knowledge. Creativity is an essential aspect of innovation. Sometimes the Creative Process is more about asking the right questions than it is about finding the right answer. It is paradoxical in that it involves both spontaneity and deliberate, focused effort. Creativity does not occur in a vacuum. Art making is a process requiring both creativity and skill, and it can be cultivated by establishing conditions that encourage and promote its development. Teachers need to be aware that the atmosphere they create for learning affects the nature of the learning itself. A setting that is conducive to creativity is one in which students are not afraid to suggest alternative ideas and take risks. The Creative Process comprises several stages: •• challenging and inspiring •• imagining and generating •• planning and focusing •• exploring and experimenting •• producing preliminary work •• revising and refining •• presenting and performing •• reflecting and evaluating The Creative Process in the arts is intended to be followed in a flexible, fluid, and cyclical manner. As students and teachers become increasingly familiar with the Creative Process, they are able to move deliberately and consciously between the stages and to vary the order of stages as appropriate. For example, students may benefit from exploring and experimenting before planning and focusing; or in some instances, the process may begin with reflecting. Feedback and reflection take place throughout the process. Taken from The Ontario Curriculum: Grades 9 and 10, The Arts, Revised 2010. L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA 5 ➜ Knock, Knock. Who’s There? Lesson 5 Grade 9, Drama, ADA1O Co-constructing Criteria Co-constructing criteria is the process of working collaboratively with students to develop the criteria and indicators for successful demonstration of knowledge and/or skills related to learning goal. See DI Assessment Guide and DI Assessment Cards. Success Criteria Success criteria provide students with a clear description of what successful attainment of learning goals looks like. When students know and understand the success criteria, they have a clearer picture of the targeted learning, and what they need to do in order to be successful. By developing success criteria early in a unit or task, students can actively monitor and self-regulate their own learning. When developing criteria: •• Describe observable behaviours in clear, detailed, student friendly language •• Create descriptions which allows for a range of performance •• Ensure that the list of criteria is manageable •• Engage students in the development process – this encourages a shared understanding of the criteria, gives students • a greater sense of control, and initiates students in the use of specific language which describes their learning When using success criteria: •• Post the criteria (e.g., on an anchor chart), and refer to it when discussing learning goals and providing feedback •• Provide students opportunities to communicate about their learning and performance, making specific references • to the success criteria •• Develop other assessment tools (e.g., checklists, rubrics) that are based on the assessment criteria, and make explicit • for students the connections •• Use anonymous samples of work, and engage students in analysing and critiquing the samples using the one of more • of the success criteria •• Provide multiple opportunities for students to analyse and critique their own work, and set goals and next steps, • if adjustments needed See DI Assessment Guide and DI Assessment Cards. Think-Pair-Share Bennett and Rolheiser (2001) describe Think-Pair-Share as “one of the simplest of all the tactics” (page 94). As pointed out by Bennett and Rolheiser and Think Literacy (page 152), students require skills to participate effectively in Think-Pair-Share: •• •• •• •• •• •• •• active listening taking turns asking for clarification paraphrasing considering other points of view suspending judgement avoiding put-downs These skills can be modeled and explicitly taught. During group work, teachers can provide oral feedback and reinforce expectations. Bennett and Rolheiser (2001) note additional considerations: •• the level of thinking required in a think-pair-share •• accountability and level of risk, e.g., are all students expected to share with the whole group? (page 94) See Think Literacy Cross-Curricular Approaches, Grades 7-12, pages 152-153 and Bennett, Barrie, and Rolheiser, Carol (2001). Beyond Monet: The artful science of instructional integration. Ajax, ON: Bookation. Guided Writing Guided writing practice provides an opportunity for the teacher to work with a group of students who need similar kinds • of support. During the guided writing, the teacher models part of the writing process, e.g., using a graphic organizer to plan • for writing, or an aspect of the form, feature, or convention of the writing. Consolidation Sentence Stems Sentence stems help prompt thinking and provide a starting point for sharing thinking. A sentence stem helps to • frame thinking and the form of the response orally or in writing. L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA 6 Monologue Planning Template 5 Ws Notes Who? Who is speaking? Who is on the other side of the door? Why? Why is the character there at this moment in time? Why is the other person behind the door? Why is he or she not responding? When? When, e.g., time of day, year, season, does this scene take place? Where? Where is this door? What? What is going on? What took place before the beginning of the monologue? What is your relationship to this person? What do you want from him or her? L I T E R AC Y G A I N S T R A N S F O R M I N G I N S T R U C T I O N A L P R A C T I C E S U P P O R T S G R A D E 9 DRAMA How this might be explicitly or implicitly evident in the monologue?