How Natural Features, Industrialization, and Ethnicity Shaped Sugar

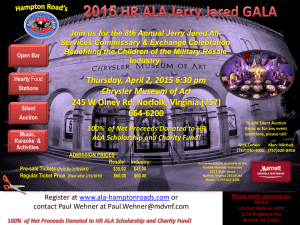

advertisement

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/history/odonnell/w1010/edit/migration/migration3.html Jacob Lawrence: The First Wave of the Great Migration (1916 – 1919) Part III, image 8 “In Chicago and other cities they labored in the steel mills… and on the railroads.” How Natural Features, Industrialization, and Ethnicity Shaped Sugar Hill Lauren DiBianca ARH 592 Professor Aaron Wuncsh 6 December 2007 Figure 1: Aerial map of present day Sugar Hill, located on NW peninsula, with 13 homes (Google Earth Image) The area currently known as Sugar Hill is a black residential neighborhood adjacent to the peninsula of Pinners Point in Norfolk County, Portsmouth, Virginia. Today, 13 homes occupy a small grid of streets framed by Scott’s Creek to the east and the Martin Luther King Freeway and Midtown Tunnel to the West and North (fig.1 ). Though one could hardly guess it now, what is currently a tiny black community resting in an enclave between transportation routes and an inaccessible creek was once a prosperous neighborhood. The history of Sugar Hill fits into the greater local and even national history of the shift from agrarian communities to industrial growth, as well as the stories of black migration and American suburbia. Because of its location near the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River, Pinners Point, and now more specifically Sugar Hill have always been important to developers as a connector, first for farmers, then railroads, and finally for automobile traffic. Sugar Hill, however, is currently denied this connectivity by the transportation that now hedges in the area. The coming of the railroad DiBianca 2 in 1886 was the defining event moving Sugar Hill from an agrarian to an industry-based community, but the nearness to the water as well as race and class of residents caused the area to retain links to its agrarian roots such that, despite vast development around it over the years, Sugar Hill remains an enclave amidst Portsmouth traffic and industry. An Agrarian History The history of Sugar Hill begins with the history of the greater area of Portsmouth, and indeed of the United States itself. In 1587 John White was nominated governor by Sir Walter Raleigh, and charged with establishing a colony at the town of Chesapeake, Figure 2: Chesapeake Bay Map, 1700s with intricate detail of the waterways (reproduced in Appendix) (courtesy Norfolk Public Library) Figure 3: Zoom on Elizabeth River in Chesapeake Bay Map, 1700s (courtesy Norfolk Public Library) within the current county of Norfolk. The name Norfolk is not in records of Virginia until 1639 or 1640, when it is mentioned as the “Upper and Lower Norfolk Counties.” Norfolk County as it exists today is a result of the 1691 division of Lower Norfolk County, its counterpart being neighboring Princess Anne County1. Maps of the region at the time are extremely detailed in terms of the accuracy of water routes through the Chesapeake Bay region (figs. 2,3), though land use is almost totally disregarded in these early depictions. 1 Watts, Leigh Richmond, Ed. by Charles B. Cross, Jr. A Historical Sketch of Norfolk County. Delivered at Berkley, July 4th, 1876, by Request of the Board of Supervisors. (Chesapeake, Virginia: Norfolk County Historical Society, 1964), p. 18. DiBianca 3 From the outset, the intricate fingers of rivers and creeks were the defining features of the area. Thus the Elizabeth River and its tributaries as transportation routes were set up as a defining element of the area even in its earliest days of discovery, and water, along with the transportation opportunities it provides, continued to hold varying but ever important roles in the development of Portsmouth, Pinners Point, and eventually Sugar Hill. Land use in Norfolk County on the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River was, until the late 1800s, characterized by an agrarian economy. Based on census information, it is known that a David Culpeper lived on the plat of land which now encompasses Sugar Hill in the early 1800s. The Culpeper name is also associated with the area as early as the 1600s; a Henry Culpeper owned land in Norfolk County in 1600s, and on 25 July, Figure 4: Norfolk County, 1773, showing farmland in Norfolk County. Scott's Creek runs through the middle of the image (courtesy Norfolk Public Library) 1698 deeded 100 acres of land to his son, Thomas2. A map of the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River, including Scott’s Creek, in 1773 clearly shows agrarian land use, with homes located close to the water’s edge (fig. 4). This places Norfolk County in sharp contrast with the developing city of Portsmouth, to the southeast, a contrast that would persist for nearly 200 years more, until the coming of the railroad to Pinners Point. 2 Norfolk County Deed Book 6, p. 155 DiBianca 4 Divided amongst children, the Culpeper land eventually landed in hands of David Culpeper and his wife, who presumably farmed as well. A map of the area in 1818 shows multiple farming families living on the Pinners Point peninsula, each with a substantial plat of land connected directly to water access (fig. 5). Figure 5: Map, Elizabeth River, 1818. Culpeper Farm located on the Western edge of Scott's Creek where Sugar Hill is now situated. (courtesy of Norfolk Public Library) In the center is the Scott farm, built in 1734, for which the creek, originally known as Church Creek, was named (Yarsinske, 213).3 David Culpeper gave the land close to Scott’s Creek to his daughters in his will, in 1825. However, these sold this 45 acre plat on the creek to a black family, the Ellets, in 1840, and lived further east on the edge of Tanner’s Creek (fig. 6). The first census data available is of the Peytons, David 3 Yarsinske, Amy Waters. The Elizabeth River. (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007), p. 213. DiBianca 5 Culpeper’s daughter, Dorcas’, family, who remained on Tanner’s Creek in the 1860s. A close look at the Peyton family census data from 1880 provides some insight into the residents of Norfolk County as they were living just before the railroad was established4. The head of house, Joshua Peyton, worked as a farmer even at the age of 71, with his wife Dorcas Figure 6: 1863 Military Map of Portsmouth and Norfolk County, with Culpeper Farm located along Tanners Creek, and Ellet home along western edge of Scott's Creek in center (courtesy Norfolk Public Library) keeping house, and their single son working as a farmer as well. The widowed Mary Culpeper, age 75, lived with them as well. Their neighbors were mostly farmers and laborers, with one merchant in the vicinity. Most blacks nearby were unable to read or write, and neither Joshua Peyton nor Mary Culpeper were able to read or write. Regarding the Culpepers’/Peytons’ sale of the land now occupied by Sugar Hill to the Ellet family, the details are up to speculation. A Joshua Peyton shows up in slave ownership records from 1850 as owning one male and one female slave. It is possible that the Ellets were his slaves, and that he sold the land to them as freed blacks. The specific Ellet family of Edward and Lovey are not visible on any census in the time, most likely because blacks were unlikely to be recorded in censuses before the Civil War. However, the Ellet’s daughter, Emeline, is documented as living on the land in 1860. She was a 4 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Inhabitants in Tanners Creek [illegible], in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 14 June, 1880. p 35. DiBianca black woman5. It is safe to say, therefore, that Edward and Lovey were black, and potentially the former slaves of the Peytons. It is also highly possible, however, that the Peytons could not afford to own slaves. While Dorcas could read and write, her husband could not, and therefore probably did not come from a wealthy family6. In this case, the Ellets may have been precursors of a later trend of black migration to Pinners Point in search of job opportunities. At any rate, when Mr. Ellet and his wife died, they left their farmland to their daughters Emeline and Mary, and their son William and his wife. The division suggests the Ellet’s knowledge of the importance of the northern end of their land for development, as it is split as a separate piece (fig. 7). This land would later be cut through by the Norfolk and Carolina Railroad running north to Pinners Point. Note the location of the homes on the map; there are 3 on the site. One seems to be at the end of the boundary cutting through the middle of the site from the west, the diagonal and winding characteristics Figure 7: Ellet Plat Division, 1882 (reproduced in Appendix) of which would suggest a private road. This home at the end of the road was most likely the Ellet, and possibly the Culpeper farm, as it is close to the river, the cemetery, and the access road. 5 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Inhabitants in Jackson Ward, in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 35 August, 1860. p 174. 6 Inhabitants in Tanners Creek Census Record, 1880 6 DiBianca 7 In the 1880 census, six years before the coming of the railroad, Emeline Ellet and her sister Martha still occupied their inherited land, Emeline then married to a William Thomas from Washington, D.C., who worked as a laborer. None of the Thomas’ two sons, aged 12 and 10, nor their daughter, age 4, worked, and Emeline kept house. They seem to have been fairly well off, along with their other neighbors. Martha also kept house, but as she was single, her daughter Lillyana was a farm hand, and her son, Robert H, a laborer, at the ages of 18 and 15. The neighbors in the surrounding area were mostly black, except for one white family, the Welsch’s. Mr. Welsch was a blacksmith, and his son a farmer. Most men in the Pinners Point region were farm laborers, with one oysterman; only one child (the Welsch boy) in the immediate vicinity attended school. Only one woman worked as a farm laborer, while others kept house7. It is unclear whether the black families worked as farm laborers on their own land, or on Mr. Welsch’s son’s farm. By this date, they were all freedmen, so it is difficult to tell; however, the fact that they are listed as farm laborers and not farmers would suggest that they were farming another’s land. Black families like the Ellets were not new to Norfolk County, but rather have been a defining population of the area since its inception, first as slaves, and then as freedmen. The overall population of the county steadily increased from 1644 on; it also became more diverse. No free blacks lived in the county until 1810, and the first year during which no slaves were listed was in 1870. Until then, slaves vastly outnumbered free blacks. Not only this, but the total number of blacks in the area increased by nearly 200% between 1860 and 1870, showing a migration of blacks to the area shortly 7 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Inhabitants in Halls Corner Voting Precinct, in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 15 June, 1880. pp. 72-74. DiBianca 8 following the land purchase by the Ellet family. Oddly enough, the peak of the population was in 1890, dropping dramatically in 1900. In 1900, Norfolk County outside Portsmouth and Norfolk was nearly 60% black, with 31,000 out of 51,000 people being free blacks (see table 1)8. As will be seen, the existing racial makeup of Pinners Point, combined with need for unskilled labor as a result of the railroad and accompanying industrial developments in and around the area, would set up the Ellet’s land to become the precursor to the black neighborhood that exists today at Sugar Hill. Railroads Define a New Landscape Speculation on the possible utility of Norfolk County as a prime railroad location began as early as 1827, as observed by an article in the Village Register and Norfolk County Advertise. The article states that commissioners and engineers of the Western Railroad returned to “this city” after looking into many other sites for the railroad. It lists many routes that the commissioners had considered, including “through Cummington to Northampton, and from Northampton through South Hadley to the three rivers, and through Ware, Rutland, and West Boylston, to the Elsebeth River,” concluding that, “in general they have found the obsticles less formidable than they had reason to expect.” 9 Though the tracks for Pinners Point’s first railroad were not laid until 1886, its foundation was based in the overwhelming rail development in the Norfolk region, and indeed throughout the nation, throughout the 1800s. Norfolk was a logical choice for this railroad boom, as much of the transportation of goods still relied on shipping; the area’s 8 Stewart, William Henry. History of Norfolk County Virginia and Representative Citizens 1637-1900. (Chicago, Illinois: Biographical Publishing Company, 1902). 9 Village Register and Norfolk County Advertise, 4 October, 1827 vol. 8 Issue 51, pg. 2 DiBianca 9 maritime connections – well known even two centuries earlier – placed it as a prime candidate for railroad connections to the northeastern United States and abroad. The first rail line to be constructed in the region was the Portsmouth and Roanoke Railroad, or the Portsmouth and Weldon Railroad, incorporated in March 1832. After a slow start, the Portsmouth based railroad was reorganized and renamed the Seaboard and Roanoke Railroad in the 1850s.10 A boom of warehouse, wharf, and rail line construction ensued, and local historian Amy Yarsinske cites that even in the railroad’s infancy, private residences were sacrificed to transportation lines – a trend later poignantly felt by residents of Sugar Hill.11 Under a new name, the Seaboard Air Line Railroad was indirectly responsible for the construction of a rail line to Pinners Point.12 During the 1880s, a ‘gentlemen’s agreement’ had reserved the harbor at Elizabeth River at Norfolk for the Seaboard & Roanoke Railroad, but both the Atlantic Coast Line and the Piedmont Air Line Route, also known as the Richmond and Danville RR, wanted access as well. In exchange for staying out of Norfolk, the Seaboard agreed not to operate in the Richmond vicinity, where the other lines had precedence. However, William P. Clyde, the owner of the R&D RR, and William T. Walters, the owner of ACL believed they could get around the gentlemen’s agreement by constructing a rail line from Pinners Point to Tarboro, rather than having a terminus at Norfolk. The line was built by the then mayor of Norfolk, Mr. Barton Meyers, and was to be financed by both RR companies, but R&D RR, later known as the Southern Railway, backed out temporarily.13 10 Prince, Richard E. Atlantic Coast Line Railroad: Steam Locomotives Ships and History. (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Wheelwright Lithographing Company, 1966) p. 19. 11 Yarsinske, Amy Waters. The Elizabeth River. (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007) pp. 266-72. 12 Prince, 19 13 Ibid. DiBianca 10 Eighteen eighty six marked the date of the charter of the first rail line running from Pinners Point, known as the Western Branch Railway. This line was chartered to run from Pinners Point and the car ferry slips of New York, Philadelphia & Norfolk Railroad (aka: Nyp ‘n N) to truck farms like those farmed by the Culpepers and Welschs in Norfolk and Nansemond Counties near the Elizabeth River’s Western Branch. 12 miles of track were laid between Pinners Point and Drivers, Virginia, with 8 miles of spurs stretching into nearby truck farms. Figure 8: Map of Norfolk and Carolina Railroad at Pinners Point, 1892 (courtesy Norfolk Public Library) After its construction between 1887 and 1888, the Western Branch Railway provided farmers in the area with a direct route to New York, Philadelphia, and Boston markets, thus beginning a new history of indirect connection to the river, rather than direct river access for each farm.14 An 1892 map depicts the railroad cutting through the old Ellet property, connecting Pinners Point to the southwest, but cutting the area now known as Sugar Hill off from the northern area, which would become Port Norfolk (fig. 8). The 14 Ibid. DiBianca 11 Norfolk and Carolina, and later the Southern Railroads connected Norfolk and Portsmouth to Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Alabama, and North and South Carolina. They transported agricultural products such as, “cotton, corn, tobacco, wheat, oats, rye, broom corn, sweet and Irish potatoes, peaches, pears, figs, grapes, and almost every fruit and vegetable that will grow out of the tropics”, and staple crops such as rice, corn, and tobacco were also important to the economy of the region.15 The Culpeper/Ellet farm may have been growing any one of these in its day. On a larger scale, the railroad development thus expanded the ‘hinterland’ of industrial areas to regions further afield.16 For the farmers near Pinners Point, this translated into a rather abrupt transition from an agrarian to an industrial economy, as well as an influx of immigrant workers, both for farming and for industrial jobs. In the most comprehensive history of Norfolk County, author William H. Stewart writes, “the railroads of this region, as well as the landowners and the people generally, are thoroughly aroused on the subject of immigration. They do not want any pauper immigration, but they do want thrifty and reputable farmers to come in and utilize the resources that are lying to waste. They realize the great benefits to the whole section that would accompany a large increase in population.”17 This way of thinking highlights the prevalent assumption that the hinterland, hitherto inaccessible to farmers due to its distance from transportation, was lying in waste, and in need of development to take advantage of its worth. 15 Stewart, 306 See Cronon, William. Nature’s Metropolis. Chapt. 3-5. for an in-depth discussion of the concept of the hinterland in relationship to industrial development. 17 Stewart, 306 16 DiBianca 12 Just two years later, the railroad and therefore those occupying the area close to Pinners Point expanded south into North Carolina. Or rather, the railroad permitted North Carolinian goods and residents to spread north to Portsmouth. In 1888 the Western Branch Railway was absorbed by the Chowan and Southern Railroad, which had been constructed by men in logging industry: Theophilus Tunis of Baltimore and Goldsborough M. Serpell of Norfolk. These entrepreneurs laid 26 miles of track south from Tunis, NC on Chowan River. Ten miles of track were added by the American Construction Company to connect north to Drivers, VA and south to Tarboro, NC, so that by 1900, the newly dubbed Norfolk and Carolina Railroad stretched 100 miles from Tarboro to Pinners Point. At this point the N &C Railroad was a subsidiary of the Atlantic Coast Line, giving the southern line access to northern ports. This port access was made possible through steam tugs which brought goods to the larger shipping ports in Norfolk to be transported up the bay. To fill this need, the N&C RR purchased the steam tug “Pinners Point” in 1891 (fig. 9).18 The railroad proved to be an important link in the Atlantic Coast Despatch – a fast running line from the south through Pinners Point and later the NYP&N terminal at Port Norfolk up to northern ports.19 The Southern Railway returned to the Pinners Point story in 1896 when it received track rights to 151 miles of Atlantic Coast Line, including the N&C RR from Tarboro to Pinners Point. J. Pierpont Morgan began the previously stalled railroad.20 Together, the two railroads constructed deep sea terminals at Pinners Point, fulfilling what contemporaries saw as a basic need of any railroad wishing to be successful. Author 18 Prince, 19 Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company. The Story of the Atlantic Coast Line, 1830-1930. (Wilmington, NC: Wilmington Stamp and Printing Company, 1930). 20 Prince, 19 19 DiBianca 13 William H. Stewart outlines the importance of this terminal to the Southern Railway as follows: “The Southern has wide ramifications and is connected with every road worthy [of] the name in the South. Nearly all of this the Southern had before it came to this port, but the port was necessary, as the Southern had no great deep-water terminus, and to keep pace with the time must have one. In looking over the coast line the very natural selection fell here, and the great plant of miles of shifting track, immense warehouses and other necessary adjuncts of a port terminal were built.” 21 Following the construction of the deep water terminus in 1900, the railroads organized the Chesapeake Steamship Company to connect them northward to Baltimore. Also in this year, the Norfolk and Carolina Railroad was consolidated into the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. The Atlantic Coast Line owned two tugs at Pinners Point: the Pinners Point (built 1891), and the Norfolk (built 1907). These tugs towed barges and ‘car floats’, as well as a passenger barge, “York,” nicknamed “Noah’s Ark.” The ‘Ark’ went from the Atlantic Coast Line in Norfolk (located at west York St) to a passenger pier at Pinners Point where it connected with trains. Freight to Norfolk went by barge to the Coast line wharf in Norfolk.22 In1898 the Richmond and Petersburg Railroad was authorized by the legislature of Virginia to purchase the Petersburg Railroad and name the consolidation (less than 100 miles) “Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company of Virginia.” On April 21, 1900, the Atlantic Coast Line RR Company of South Carolina, Wilmington and Weldon, Norfolk and Carolina, and other railroads were sold to and merged with the ACLRC of VA, 21 22 Stewart, 306 Prince, 19, 53 DiBianca 14 which then changed name to Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company. All total, this line ran from Richmond to Charleston, with branch and feeder lines in Virginia and North and South Carolina. By 1925 the Atlantic Coast Line had expanded with double tracks from Richmond to Jacksonville.23 The junction at Pinner’s Point no doubt benefited from this expansion, as was evidenced by its swift development once the Ellets sold their land to developers in 1900. Land Development and Sugar Hill’s Golden Years During this time was when the value of the Culpeper/Ellet land drastically shifted from one of agrarian value to one of transportation value, through the building of the railroad. This transition is made startlingly clear on this land in particular, as the railroad cut through the land, resulting in its development – moving from single family ownership and farming to sliced up parcels owned by developers and later the workers of Sugar Hill. As predicted by the division of the Ellet land in 1880, the coming of the railroad would have dramatic impacts on both land use and settlement patterns to the south of the Pinners Point terminals. In 1894, Emeline put her land in the holding of Norman Cassell, a trustee, and the firm of T.J. Wool, H.L. Maynard and A.J Phillips. Seemingly, she fell into financial trouble, and the land was held for her, and sold in order to pay off her debts.24 Her nephew, Robert H. Elliot (or Ellet) likewise sold his land in 1897 to the Pinner’s Point Home Company for development. A close look at the plats owned by the Pinners Point Home Company in 1897 and 1900 shows the developers’ intentions to fill their newly 23 24 Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company, 16 Norfolk County Grantor Book 234, p. 533 DiBianca 15 purchased land with dense housing (figs.10-11). The lots as they are laid out in the plat maps are a mere 25 by 85 feet, with some larger plats, lot 79 in particular left for Emeline Thomas to live on, and a few other blocks of lots labeled with her name but subdivided nonetheless. Though the lots as drawn on the 1900 map extend into the creek, Sanborn maps of the time show no alteration to the shoreline, suggesting that the home company did not invest as much in the development as originally intended. The plat maps also give a good depiction of the juxtaposition of Figure 10: Plat Map of Pinners Point Home Company Land, 1897 (reproduced in Appendix) planned housing with the railroad. The area now known as Sugar Hill occupies the land to the south of the railroad on the maps, though the names of all of the roads have changed over time. It is clear that though this area is close to Figure 11: Plat Map of Emeline Ellet's/ PPHC land, 1900 (reproduced in Appendix) the railroad, it is not nearly so much so as the proposed development to the north. Though the land labeled as ‘Rodger’s Land’ was later developed, Sugar Hill retained its separation from the railroad over the years because of the arm of Scott’s Creek just to its north. Soon after being sold to the Pinners Point Home Company, Emeline Thomas’ land developed into a workers community. Based on Sanborn maps, the first homes appeared in the area between 1900, when the land was sold, and 1920. By 1920, tiny twelve foot wide duplexes occupied the 25 by 85 foot lots, doubling the presumably DiBianca 16 intended occupancy (fig.12). Sharing parti-walls maximized land utility and materials, but it is unclear whether this density was necessitated by the low-salaried residents, or a decision of the developers to get the most out of the land as possible. Presumably, it was a combination of both. Migrating workers would have wanted their own home as a part of the suburbanization trend of the era, and the Pinners Point Home Company monopolized on this desire by creating the smallest version of this goal that they could. The Figure 12: 1920-1950 Sanborn Map, showing Sugar Hill in right center (Courtesy Portsmouth Public Library, reproduced in Appendix) density, however, is most likely what gave the area its neighborhood quality, linking residents together in ways now but fond memories of the few remaining elderly residents of Sugar Hill. It seems the class and racial characteristics of the developed Pinners Point area was grounded in the existing population of the area; as discussed earlier, in the 1880 census, the area around Pinners Point was already made up of a heavily black population. The community of laborers that migrated to the area was similarly black, unskilled workers. One could speculate that the farm labor force in this area was simply transferred over to the railroad labor force, and of course supplemented by heavy migration from DiBianca 17 North Carolina and other southern states. The demographic, at least, retained its ethnicity during industrialization – and continuing to present day. A publication by the Atlantic Coast Line public relations department in 1930, functioning as an advertisement for the railroad, also cites the importance of laborers in its construction. It states, ”The Atlantic Coast Line, however, is not merely a big railroad. The constituent companies of the Atlantic Coast Line were built and operated by the people of the sections they served, and when merged into the present organization their employees brought with them that tradition of loyalty to their employers, pride in their occupation and intimate knowledge of the people and transportation needs of their communities, which makes the Atlantic Coast Line so integral a part of the economic life of the Southeast.”25 Though Pinners Point and the Ellet/Culpeper land was not formally owned by the Pinners Point Home Company until 1900, it is likely that workers moved to the area just after 1880 in order to construct the Norfolk and Carolina Railroad, later moving into the shotgun homes so conveniently located next to their place of work. The Industrial Labor Force The development of Sugar Hill falls within a larger trend of black suburbanization occurring in the early 1900s, during the Great Migration, a movement of over 1 million blacks out of the South and into northern cities. While most migrants moved into the city, approximately 15 percent of such migrants between 1910 and 1940 settled in suburbs. In an article focused on Cleveland suburb Chagrin Falls Park, Andrew Wiese describes a 25 Atlantic Coast Line, 20 DiBianca 18 neighborhood which must have been very like Sugar Hill, providing a framework for its development, and connecting Sugar Hill to a larger trend.26 While Virginia is just below the Mason Dixon line, the Portsmouth area grew steadily with an influx of freed black workers. By 1910, the Western Branch District of Norfolk County was in the middle of its inevitable transition from an agrarian to an industrial workforce. Both 1910 and 1920 census records show the majority of Sugar Hill’s original residents as being North Carolinians who moved to the area to work on the railroad, which put Pinner’s Point on the map.27 Land Developers Propaganda published by the railroad companies may have contributed to the population influx in Norfolk in the early 1900s by appealing not only to those coming to work on the railroad, but to those who would utilize the new transportation and development in the south to reap its benefits. A pamphlet published by the Norfolk and Western Railroad in 1910 entitled, ‘Go South Young Man” quotes Chauncey Depew in an address to Yale alumni as saying that the land in Virginia is one of many natural resources that are of yet untapped, that Virginia has, “the best climate in the world,” and, “conditions of health that are unparalleled.” At the bottom of the pamphlet, readers are urged to go to Virginia with an increasing level of excitement: 26 Wiese, Andrew. “The Other Suburbanites: African American Suburbanization in the North Before 1950,” Journal of American History 85 (March 1999), p. 1496. 27 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population. Western Branch District, Norfolk County, Virginia. 16 Apri,l 1910. Sheets 1-2A. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. DiBianca 19 “GO TO VIRGINIAWhere the Development is the Widest! Where the Opportunities are the Greatest!! Where all are Welcome!!!”28 Migrants of the sort who most likely responded to this call, however, would more likely have been investors in the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad than laborers who built it up. Those who bought and developed the Ellet’s land into Sugar Hill led very different lives from those who occupied it. The man who secured Emeline Ellet’s property in 1900, TJ Wool, was a general practice lawyer living in Norfolk proper. Originally from New York, he lived in Petersburg at the age of 14, where his father was a sash and door maker. The family lived at 101 Bollingbrook Road. Presumably, this was a middle to upper class area of the city, as the 1880 census shows that many of the Wools’ neighbors had servants in their homes.29 Between 1880 and 1920, Mr. Wool moved to Norfolk in Madison Ward.30 The president of the Pinners Point Home Company also came from an upper to middle class background. In 1910, just as Sugar Hill was beginning to flourish, Mr. Jonathan L. Watson was the president of a bank at 47 years old. He and his family, consisting of a wife, two daughters, and a son, lived at 225 Hatton Street in Portsmouth City.31 28 Depew, Chauncey M. “Go South, Young Man.” As referenced in a pamphlet produced by the Norfolk and Western Railroad Company. (Roanoke, Virginia: Norfolk and Western Railroad Company, ca. 1910). 29 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Inhabitants in Petersburg, in the County of Dinwiddie, State of Virginia. 9 June, 1880. p 11. 30 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1920 Population. Madison Ward, Norfolk City, Norfolk County, Virginia. 9 January, 1920. Sheet 5A. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. 31 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population. Portsmouth City, Norfolk County, Virginia. 19 April, 1910. Sheet 2B. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. DiBianca 20 An Unlikely Suburb Blacks moving to the area may have been looking not only for employment, but also for the elusive construct of the suburban dream. Wiese points out that suburbanization was not a phenomenon experienced solely by white middle and upper classes, but that blacks and other classes were often just as eager to flee the city to find a better life32. Just outside of more northern cities, blacks could afford “many of the same things as other suburbanites, including homes of their own, a bucolic landscape, and family-centered community life.”33 Thanks to the railroad, residents found all of these in Sugar Hill. Wiese states that, like other suburbanites of the era, black suburbanites “rejected city living, and they re-created rustic landscapes reminiscent of the region from which most had come.”34 While this was decidedly true in the case of Sugar Hill, as is still evidenced today by the large flower and vegetable gardens in many side yards, it seems that this ‘rustic landscape’ stemmed less from an aesthetic desire to recreate a rural landscape than a more basic need for survival. Wiese addresses this trend as well, stating that, “workers were more likely than middle-class suburbanites to view their home as a basis for economic survival – as a source of income through renting rooms, as a supplement to wages through garden produce and backyard livestock…”35 The 1910 census shows a clear shift in the economy of the area around then developed Sugar Hill (see table 2 ). The Culpepers still lived next to one another. Presumably brothers, both Joshua and David Culpeper worked on the river as an 32 Wiese, 1497 Ibid, 1496 34 Ibid, 1499 35 Ibid, 1500 33 DiBianca 21 oysterman and a fisherman, respectively. David’s son, David R. Culpeper, worked in a shop as a molder, showing even within the family a shift from an agrarian focus to one of industrial labor. Neighbors demonstrate the same trend: established residents worked in the agrarian sector either on the land as farm laborers, or on the water as oyster- or fishermen. Newer workers, often from North Carolina, and many of them mulatto, were more likely to be employed in industrial jobs.36 Perhaps because of lower wages, or perhaps due to the development of the area and a perceived need for ‘more’ to survive, the female population of Sugar Hill became more involved in the work force in the 1900s. Thus around 1910 the Western Branch of the Elizabeth River (as the district was named) experienced a shift in economies, which in turn brought in a new labor force, laying the social framework for the success of Sugar Hill in the 1920s. Upon first being built, the neighborhood now known as Sugar Hill was much more of a suburb than its current state as an enclave surrounded by the swooping transportation lines of Portsmouth would lead one to believe. By studying Sanborn maps from the time, it becomes apparent that the area was not of importance to insurance companies until the 1920s, and even then was on the fringe of Portsmouth’s quickly expanding development. But the homes built by the Pinner’s Point Home Company differed from the prominent suburban ideal of being located at a commuting distance from employment. Residents were literally hemmed in by the railroad as it cut through the west side of the development and north to the yards on Pinner’s Point. Residents’ labor was therefore ever-present on this side of the neighborhood. 36 U.S. Bureau of the Census. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population. Western Branch District, Norfolk County, Virginia. 16 Apri,l 1910. Sheets 1-2A. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. DiBianca 22 However, residents did have a natural feature which provided both a physical and a mental barrier between their home and working lives. Though not of great width or depth, Scott’s Creek acted as the distancing agent in this effective suburb, its watery surface providing the healing rural landscape which suburbanites so desired, while a bridge spanning the banks linked residents to work and social spaces. The streetcar, in this case, was essentially replaced by a footbridge as both the dividing line and the link between home life and labor. Unlike so called ‘streetcar suburbs,’ which also relied on transportation lines for their development, Sugar Hill was developed as a workers’ town, serving the railroad rather than commuting on it.37 However, like the streetcar, the railroad connected the area to a vast network of truck farmers, distributors, and large industrialized cities. A streetcar line to the north of the railroad connected residents to the northwestern community of Port Norfolk, but this being a predominantly white community, the connections were not so strong as those within the community of Sugar Hill itself. Thus Sugar Hill embodies Weiss’ argument that, “In contrast to the middle-class model, the metropolitan fringe before 1945 was a variegated landscape that included factories, workers’ housing, and ethnic white enclaves, as well as middle-class commuter suburbs.”38 A glance at the Sanborn map spanning from 1920 to 1950 shows this variety in the relatively small area around Sugar Hill, with the railroad, a factory, and housing all functioning side by side (fig.12). This Sanborn, with its overlays and deletions, points to the 1920s and decades directly surrounding as the clear heyday of Sugar Hill. The area boasted five stores, two 37 For an in-depth discussion of streetcar suburbs, see Borchert, James, “Visual Landscapes of a Streetcar Suburb,” chapter 2 in Paul Groth and Todd W. Bressi, Eds., Understanding Ordinary Landscapes 38 Wiese, 1499 DiBianca 23 churches, and a school by 1921, but by 1950 one store remained, and many homes had been replaced by larger single family homes, or completely removed. Sugar Hill thus falls in between Paul Groth’s defined ‘workers’ cottages’ and ‘minimal-bungalow’ districts. While the neighborhood was planned, as indicated on plats and Sanborn maps, to be somewhat uniform – like workers cottages - over time it was more of an accretion of forms and uses based on user needs – like Groth’s defined minimal bungalow homes. Present day development testifies to this trend; many homes in the neighborhood today are duplexes converted into single family homes. Just as the development of Pinner’s Point was jumpstarted by the railroad, so too were the glory days of Sugar Hill in the 1920s most likely a result of the accompanying success of the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. In a pamphlet produced in 1924, the railroad boasts of a comeback after federal ownership of the railroads ended in 1920, writing, “For the American railroads, starting in 1920, bunged up by their rough handling under Federal control, crippled by injury to their credit, and with the hardest schedule they had ever faced, have staged a comeback that has been more spectacular in its own way than a world flight or the winning of the Olympic games, a world’s series or a football championship.”39 The pamphlet cites a surge in efficiency in the past 4 years due to raising 3 billion dollars, and claims that the rail line in 1924 was moving 10 percent more freight per week than 5 years previous. But the railroad was not the only defining characteristic of the lives of the workers she employed from Sugar Hill. Drawings by current resident of Sugar Hill, Billy Stanley, composed for a “Pinner’s Point Reunion” in the 1990s highlight his experience of the neighborhood in 39 Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company. More World’s Champions. (Wilmington, North Carolina: Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company, 1924). DiBianca 24 the 1920s as one dominated by both the railroad and the creek. While the railroad was clearly important as a source of income for men, and the nearby basket factory as the same for women (figs.13-15, in appendix), the creek seems to have embodied suburban ideals for those living in Sugar Hill in the 1920s and surrounding decades. Mr. Stanley depicts the creek as a source of leisure; in one drawing he recalls a Saturday on the creek bank, with crabs, watermelon, and lemonade for all (fig. 16, in appendix). Scott’s Creek was also, like the undeveloped land in many workers’ suburbs, a source of sustenance: two drawings show men pulling crabs out of the water, and another describes washing day at the creek (fig. 17, in appendix). The creek served as a connection, as shown in his drawing of the bridge across the creek to ‘Pleasure Hill’ – where both the railroad and a community center drew residents (fig. 18, in appendix). And the water had spiritual significance as well; in perhaps the most poignant of Mr. Stanley’s drawings, a believer is being baptized in Scott’s Creek (fig. 19, in appendix). These drawings make it clear that though the land and the lives of those who occupied it were drastically altered by the railroad at Pinners Point, yet the creek gave the community of Sugar Hill a link to nature and the area’s agrarian past. This juxtaposition is important, as it highlights the water’s influence on the site as both one of the inevitable process of industrialization, but also as a means of retaining its roots. DiBianca 25 Present Day Sugar Hill On visits to Sugar Hill, I was lucky enough to talk to some of the people who still call it home. A current resident of Sugar Hill remarked that he remembers playing in the now nonexistent graveyard during school. Ms. Yvonne Stanley fondly reminisced about the grand homes, as well as her old home, and recalled playing in Scott’s Creek growing up. The graveyard is no longer visible, though it is possibly buried under the remnants of the razed school building. Grand homes exist only across the freeway in Port Norfolk – the freeway that covers where Ms. Stanley’s old home once stood. And Scott’s Creek? It remains, polluted, seemingly almost stagnant, and inaccessible to residents due to years’ worth of garbage dumped on the banks by the city of Portsmouth. Since 1952, when the steam tug lines ceased to run out of Pinners Point40 and the colored school in Sugar Hill was torn down, the community has been physically divided, and all but destroyed, by the transportation that has defined the area for centuries. The ethnicity of the area surely played a role in its being cut through by the Martin Luther King Freeway and the Norfolk-Portsmouth Tunnel in the 60’s, and may have possibly played a role even in the 1880s as the railroad sliced through Emeline Thomas’ land. Remarkably, however, the tiny but tight knit community survives. Though development has thrived on a transportation-related connection to the water and essentially wrenched riparian rights from community members’ hands, Scott’s Creek has ultimately saved Sugar Hill. The wooded western edge of the community is a stark contrast to the overpass clearly visible in the east. This wood and the creek beyond are remnants of the long past agrarian nature of Norfolk County, a nature preserved by Sugar Hill’s inhabitants over the years out of both necessity and a desire for suburban life. 40 Prince, 53 DiBianca 26 Though the area’s development has been consumed by the utility of water much like that described by Richard White in his book The Organic Machine41, residents held onto a link to nature by focusing on the water as well because of suburban ideals, a basic need for survival, and a current sense of nostalgia for the neighborhood they once knew. Figure 20: View of Scott's Creek in Present Day Sugar Hill (courtesy of author) 41 White, Richard. The Organic Machine. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), introduction and chaps. 1-3. Works Cited Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company. More World’s Champions. (Wilmington, North Carolina: Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company, 1924). Atlantic Coast Line Railroad Company. The Story of the Atlantic Coast Line, 1830-1930. (Wilmington, NC: Wilmington Stamp and Printing Company, 1930). Depew, Chauncey M. “Go South, Young Man.” As referenced in a pamphlet produced by the Norfolk and Western Railroad Company. (Roanoke, Virginia: Norfolk and Western Railroad Company, ca. 1910). Groth, Paul. “Workers’-Cottage and Minimal Bungalow Districts in Oakland and Berkeley, California, 1870-1945,” Urban Morphology 8, no. 1 (2004): 13-25. Newby-Alexander, Cassandra, Ph.D, Mae Breckenridge-Haywood, and the African American Historical Society of Portsmouth. Portsmouth Virginia. Black American Series. (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2003). Norfolk County Historical Society of Chesapeake, Virginia. An Historical Review. (Chesapeake, Virginia: The Society, 1966). Prince, Richard E. Atlantic Coast Line Railroad: Steam Locomotives Ships and History. (Salt Lake City, Utah: The Wheelwright Lithographing Company, 1966). Stewart, William Henry. History of Norfolk County Virginia and Representative Citizens 1637-1900. (Chicago, Illinois: Biographical Publishing Company, 1902). Village Register and Norfolk County Advertise, 4 October, 1827 vol. 8 Issue 51, pg. 2 Watts, Leigh Richmond, Ed. by Charles B. Cross, Jr. A Historical Sketch of Norfolk County. Delivered at Berkley, July 4th, 1876, by Request of the Board of Supervisors. (Chesapeake, Virginia: Norfolk County Historical Society, 1964). White, Richard. The Organic Machine. (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), introduction and chaps. 1-3. Wiese, Andrew. “The Other Suburbanites: African American Suburbanization in the North Before 1950,” Journal of American History 85 (March 1999): 1495-1524. Yarsinske, Amy Waters. The Elizabeth River. (Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, 2007). Census Records U.S. Bureau of the Census. Inhabitants in Halls Corner Voting Precinct, in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 15 June, 1880. pp. 72-74. USBC. Inhabitants in Jackson Ward, in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 35 August, 1860. p 174. USBC. Inhabitants in Petersburg, in the County of Dinwiddie, State of Virginia. 9 June, 1880. p 11. USBC. Inhabitants in Portsmouth, in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 12 June, 1880. p 44. USBC. Inhabitants in Tanners Creek [illegible], in the County of Norfolk, State of Virginia. 14 June, 1880. pp 35, 37. USBC. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population. Western Branch District, Norfolk County, Virginia. 16 Apri,l 1910. Sheets 1-2A. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. USBC. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910 Population. Portsmouth City, Norfolk County, Virginia. 19 April, 1910. Sheet 2B. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. USBC. Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1920 Population. Madison Ward, Norfolk City, Norfolk County, Virginia. 9 January, 1920. Sheet 5A. Prepared by the Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of the Census. USBC. Twelfth Census of the United States, Schedule No. 1. – Population. Third Ward, Portsmouth, Norfolk County, Virginia. 8 June, 1900. Sheet 7. Table 1: Population of Norfolk County (From A History of Norfolk County and Representative Citizens, pp. 318-320) Population of N.County over time, based on titheables (all free male persons over the age of 16, extended to cover all male servants) Year Population 1644 296 1690 1097 Split be/ Princess Anne and Norfolk Counties 1691 772 1740 1799 1789 4247 Norfolk County Population Year 1790 14524 1800 1810 1820 1830 1840 1850 1860 1870 1880 1890 1900 Total 9179 19419 22872 23943 24896 27569 33036 36227 46702 58657 77038 50780 White 11960 13400 13260 13314 15444 20329 24357 24380 29197 37497 19113 Free 5345 1498 1898 2300 2307 2803 22320 29453 39,478 31189 Slaves Chinese, Japs. & Inds. 7459 9472 9185 9594 99735 10400 9004 63 2 7 63 478 Population of Norfolk County (outside of Norfolk and Portsmouth) in 1900 by districts: Butts Road Deep Creek Pleasant Grove Tanner’s Creek Washington (including Berkley town – 4988) Western Branch Total 1821 3454 2974 13077 11515 17939 50780 Table 2: Western Branch Economy, 1910 Agrarian Job Farmer Oysterman Farmer Farmer Fisherman Farm Laborer Farmer Farmer Oysterplanter Farmer Oysterplanter Oysterman Oysterman Fisherman Farm Laborer Farm Laborer Oysterer Farm Laborer Total NC VA Female White Black Mulatto Location Truck River Truck Truck River Working out Truck Truck River Truck River River River River Working Out Working Out River Working Out Race W W W Mu Mu B W W W W W W W W Mu Mu Mu Mu Age 45 M 25 M 56 M 27 M 47 M 65 M 52 M 57 M 45 M 54 M 47 M 72 M 44 M 50 M 39 M 27 F 32 M 28 F Home State NC VA VA NC VA NC VA VA VA VA VA VA VA VA VA VA VA VA Household Status Head Head (5 kids none work) Head Head (Hodges) Head Head Head (R.Shea) Brother (W. Shea) Brother (R. Shea) Head (J. Shea) Head (E. Shea) (non-work:3 children, sister in law ) Father (John B. Cotton Sr.) Head (Joshua Culpeper - 4 children, none work) Head (David Culpeper - 3 children, 1 work) Head Wife Head Wife of above 18 3 15 2 11 1 6 1 of 3 Industrial Job Box Maker Car Repairer Blacksmith Bolt__ Machinist Helper Book Keeper Brass Finisher Machinist Boilerman Brakeman Fireman Fireman Freight Trucker Brakeman Laborer Sectionman Trucker Se___ Location Hoisery Mill Railroad Railroad Rail Road Shop Railroad Packing House Mechanic Shop Railroad RR RR Locomotive Navy Yard RR RR RR RR Chemical Factory RR Chemical Factory Brakeman RR Machinist Barrel Factory Nightwatchman RR Driller Machine Shop Molder Shop Car Cleaner RR Fireman Barrel Factory Section Man RR Laborer Factory Laborer RR Truckee Chemical Factory Truckee Chemical Factory Total NC VA Female Race W W W W W W W W B B B Mu Mu Mu Mu Mu B B B B W W W W Mu Mu Mu Mu Mu Mu Mu 31 13 18 2 Age Home State 23 F VA 28 M VA 28 M VA 16 M VA 36 M (cuVA 27 M VA 25 M VA 25 M VA 44 M VA 36 M NC 34 M NC 33 M VA 27 M VA 35 M NC 28 M NC 24 M NC 31 M NC 35 M VA 32 M VA 30 M NC 35 M NC 49 M VA 47 M VA 23 M VA 35 F NC 39 M NC 38 M VA 20 M VA 40 M NC 19 M NC 17 M NC White Black Mulatto 12 7 12 Household Status Daughter Head Son of 56 M Head Brother Lodger Head Head (5 kids none work) Head Head (w/ adopted son) Head Lodger Lodger Lodger Head Brother of above Son of left Brother in Law of above house painter Head Head (John B. Cotton, Jr.) Son (David R. Culpeper) Head (Lewis) Lodger w/ Lewis Lodger w/ White Brother in law of L Head (Bowden) Son (Bowden) Son (Bowden) 2 of 3 Other Job Painter Painter Cook Painter Laundress Laundress Keeper Laborer Laundress Painter Carpenter Carpenter Laundress Total NC VA Female White Black Mulatto Location House House Private Family House At Home At Home Boarding House Odd Jobs Private Family House Boat House Working Out Race W Mu Mu B B B Mu B B W W W Mu 13 6 5 6 4 5 4 Age 28 M 27 M 18 F 50 M F 41 24 F 21 F 50 M 30 F 54 M 52 M 25 M 30 F Home State GA SC NC NC NC NC NC VA VA NC VA VA VA Household Status Head Head Lodger Head Wife Head Head (2 children don't work) Head (6 children don't work, widower) Daughter of above Head Head (K. Shea) Son (John, of J. Shea) Head (White) Total NC VA Female White Black Mulatto Overall Totals 62 22 38 10 27 13 22 3 of 3 Figure 2 Appendix 1 Figure 7 Appendix 2 Figures 10,11 Appendix 3 Figure 12 Appendix 4 Figure 13 Appendix 5 Figure 14 Appendix 6 Figure 15 Appendix 7 Figure 16 Appendix 8 Figure 17 Appendix 9 Figure 18 Appendix 10 Figure 19 Appendix 11