Religious Satire in Hollywood: How Borat and Saved! Utilize the

advertisement

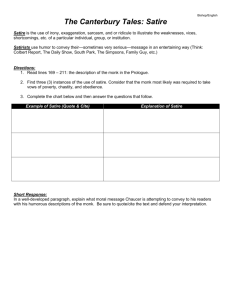

Religion. Popular Culture. If you are anything like me, you’re probably wondering right about now how these two seemingly antithetical categories fit together. Religion is sacred; traditional; reverent. Pop culture is vulgar; ephemeral; profane. Religion is Jesus; Vishnu; Muhammad. Pop culture is Madonna. Or so I thought when I first took a seat in Professor Dowland’s “Religion and Popular Culture” class. Together, we engaged in a multitude of contradistinct cultural “texts,” ranging from South Park episodes, to Jay-Z music videos; Mario Puzo’s The Godfather to footage of the Cameron Crazies during Duke basketball games. Soon I realized that although religion and popular culture may appear to be unrelated fields of inquiry, the two are richly and complexly interwoven. I found myself curiously interested in this relationship and began asking questions: What aspects of religion are present in pop culture? Even more intriguing, what aspects of pop culture are included in religion? What can popular culture teach us about religion or contribute to a religious dialogue? As the semester progressed, I narrowed my interest to a particular aspect of pop culture—satire. After being assigned to watch an episode of South Park for homework, and reading a number of articles from The Onion, it occurred to me that this particular form of cultural commentary possessed a unique ability to address taboo religious topics, precisely because it’s offensive. South Park provided a space for certain religious dialogues which, ironically, couldn’t even take place in a church or temple. Yes, you heard it here first; I learned things about religion from the gang from South Park, Colorado. And ultimately I learned things about religion from Sasha Baron Cohen’s Borat, too. And so the inspiration for this paper about religion sprang from the head of irreverent comedy (not exactly the head of Zeus…but close). 40 Religious Satire in Hollywood: How Borat and Saved! Utilize the Offensive Art to Foster Interreligious Dialogue Paul Neal Jordan Writing 20 (Spring 2010): Religion and Popular Culture Professor Seth Dowland D uring the 2008 presidential campaign, Saturday Night Live featured a sketch in which Sarah Palin, portrayed by Tina Fey, and Hillary Clinton, played by Amy Poehler, co-host a news conference in which they speak out against the dangers of sexism in politics. A dolled-up Fey stands in contrast to Poehler who wears a masculine military-cut grey business suit. Among the gems from the “broadcast”: Poehler “I believe diplomacy should be the cornerstone of any foreign policy” Fey “And I can see Russia from my house!” Poehler “I don’t agree with the Bush Doctrine” Fey (giggling) “And I don’t know what that is” Satirical shows, magazines, movies, art, and other mediums are tacitly granted a sort of take-no-prisonerslicense which allows them to approach the taboo while protecting them from much of the potential backlash. Fey “Stop using words that diminish us, like pretty, attractive, beautiful…” Poehler “…boner-shrinker” A subsequent Newsweek magazine cover featuring Palin sexily clad in a slimming training top and black spandex running shorts drew intense criticism for being politically insensitive and sexist. Yet the SNL sketch was met (largely) with praise, temporarily boosting the ratings of the show. The disparate public reactions were intriguing. After all, while many attacked the magazine cover as an attempt to belittle Palin, the SNL skit also clearly reduced her to a Barbie-doll with neither brains nor a substantive political platform. The sketch overtly suggested that Sarah Palin was soccermom sexy but clueless about politics, and that many people hate Hillary Clinton because they think she looks like a man. So to what can we attribute these disparate public reactions? It’s simple really — Newsweek is a news magazine, and SNL is, well, a joke. Whereas a legitimate news source like Newsweek or the Wall Street Journal could never explicitly call Clinton a “boner-shrinker,” SNL is not bound by the same limitations. As a satiric cultural commentator it has the freedom to say, and do, things that would be considered utterly unacceptable in more formal settings. It is understood that satire, as a medium, tends to attack “pretense and stupidity”1 without regard for political correctness. As a 1 Richard Bridgman, “Satire’s Changing Target,” College Composition and Communica tion 16 (May 1965): 85 - dices and biases. As the taboo is removed, all the subjects of religious satire — the stereotypes, fears, hypocrisies, and illogic — are simultaneously rendered accessible for examination. This transparent atmosphere provides the foundation for what Bronwen Low and David Smith call “satire’s power to re-educate.”5 By looking directly at two cinematic examples of religious satire in popular culture — Baron Cohen’s Borat and Brian Dannelly’s Saved! — we can see satire’s peculiar ability to foster reflection of and conversation about taboo religious topics, and examine its ability to reshape people’s religious attitudes, perceptions, and prejudices. Because of these two aspects of satire — the protective shield it provides, coupled with our culture’s taste for its acerbic tone— satiric religious commentary may just be the most honest and candid mode Ironic Satire in Borat of religious commentary The film Borat depends heavily (though not exclusively) upon irony to achieve its satiric thrust. As Low and Smith note, comedic irony often involves the author saying the opposite of what he really believes, deliberately making absurd and inflammatory assertions in order to provoke and elicit reaction for pedagogical purposes. This is exactly what Baron Cohen attempts to do in Borat: the film is inflammatory, but “for the larger purposes of social, political, and cultural critique.”6 Perhaps the best way to begin looking at this element in Borat is by answering the question posed by Low and Smith in their essay “Borat and the Problem of Parody”: why do we laugh at Borat, and what are we laughing at? Baron Cohen qua Borat is a homophobic, racist, misogynistic anti-Semite — though here we will focus solely on his anti-Semitism. As a prominent television reporter from Kazakhstan, he comes to America in search of a cultural panacea for what he perceives to be his country’s three systemic problems: “economic, social, and Jew.” As he and his producer trek across the United States they commit a multitude of social faux pas. Borat proclaims that they must drive, not fly, from California to New York lest the Jews plan another September 11th. They stop for drinks at a countrywestern bar and Borat performs a Kazakhstani available. TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX result, satirical shows, magazines, movies, art, and other mediums are tacitly granted a sort of take-no-prisoners-license which allows them to approach the taboo while protecting them from much of the potential backlash. Satire’s ability to engage in politically incorrect — or maybe more appropriately, politically impolite — conversations is crucial to the broad cultural discussions surrounding religion. Like so many other dialogues which often require a restrained and censored rhetoric — namely ra cial, political and gender issues — religious dialogues are often treated with über-sensitivity. Elisha McIntyre argues that “religious faith has become the last taboo.”2 This, coupled with the argument that Richard Bridgman articulates in his essay “Satire’s Changing Target” — that a poly-cultural America with its manifold creeds and persuasions fosters an “impulse to hospitalize”3 everybody’s opinion — explains the difficulty our culture has criticizing religion in a public forum. Often, this impulse is so prevalent that it suppresses meaningful inter-religious conversation, substituting instead a misplaced sense of tolerance — a tolerance which stems from a fear of offending — in lieu of robust and rigorous dialogue. Satire is the lone medium unaffected by this phenomenon. The “shield” which its biting humor provides is the respirator that allows these choked conversations to breathe. Perhaps more importantly, as Bridgman also argues, Americans, having a taste for the acerbic, tend to embrace this form of criticism. As he notes, “After years of eating honey, Americans are suddenly finding the taste of vinegar is sweet.”4 Because of these two aspects of satire — the protective shield it provides, coupled with our culture’s taste for its acerbic tone — satiric religious commentary may just be the most honest and candid mode of religious commentary available. The “shield” renders authors able to say exactly what they see, feel and think, and as a result their product is keen, pure, and unfiltered. This unadulterated honesty then allows the audience to examine its own preju- 2 Elisha McIntrye, “Can True Love Wait? Christian Morality Meets Adolescent Sexuality in Teen Film,” in The Eternal Sunshine of the Academic Mind: Essays on Religion and Film, Sydney Studies of Religion (2009), 1. 3 Bridgman, 85 4 Ibid. 5 Bronwen Low and David Smith, “Borat and the Problem of Parody,” Taboo 11 (Spring-Summer 2007): 30. 6 Ibid., 28 41 folk song, “Throw the Jew down the well.” While staying at a bed-and-breakfast they discover that the patrons are Jewish and flee in panic, throwing American dollars at the cockroaches who they believe to be transfigured Jews. After contemplating a return to New York where “there are no Jews,” the pair resolves to buy a gun to defend themselves. Borat diligently inquires of the salesman, “Which one is best for shooting Jew?” The final scene of the movie is a look at how Borat’s “cultural learnings” have reshaped his village in Kazakhstan. Among other changes, the village adopts Christianity, along with a conversion process that entails crucifying a Jew. The irony? Baron Cohen is a Jew. The ostensibly anti-Semitic plot of the film is indeed not anti-Semitic at all. Rather, as Low and Smith suggest, Cohen is “saying” the exact opposite of what he really believes in order to illustrate underlying prejudices to wards the Jewish community. This tactic of “saying the opposite” is hardly novel: Twain utilizes it when Huckleberry Finn proclaims that he must be destined for “everlasting fire” for “helping a nigger.”7 Voltaire uses it when Candide becomes startled to learn that there are no priests in Eldorado: “What! You have no monks…having everyone burned alive who is not of their opinion?”8 Swift exploits it in his Modest Proposal by suggesting that “a young child is most delicious, nourishing, and wholesome food” and as such should be eaten to prevent the country’s aristocracy from starving.9 In reality, Twain was condemning slavery, Voltaire the Catholic Church, and Swift the socio-economic inequities of Ireland. In the same vein, Cohen’s use of ironic satire should be understood not as an engendering of racial and religious hatred, but as a condemnation of these prejudices. Cohen’s “jewish-ness,” therefore, serves as a facilitator of this broader goal. If an Aryan Brother were to ask “Which gun is best for shooting Jew?” it wouldn’t be funny; it would be racist. But as Christine McMorris notes in “Borat’s Religious Provocations,” Cohen’s use of humor “unmask[s] the absurd and irrational side of anti-Semitism.”10 But it is not only the fact that Cohen is a Jew which allows him to make such outrageous statements: rather, the more nuanced matter of intent (as was the case with Twain, Voltaire and Swift) is also important. Cohen’s goal is to condemn racial prejudices — if an ignorant audience misunderstands the message, it presents an entirely different 7 Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Puffin Classics (New York: Puffin, 1995), 280-283. 8 Voltaire, Candide, or Optimism, Penguin Classics (London: Penguin Classics, 2006), 47. 9 Jonathan Swift, “A Modest Proposal,” in A Modest Proposal and Other Writings, Penguin Classics (London: Penguin Classics, 2009), 232. 42 10 Christine McCarthy McMorris, “Borat’s Religious Provocations,” Religion in the News 9 (Winter 2007): 19-21. TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX Cohen is “saying” the exact opposite of what he really believes in order to illustrate the underlying prejudices towards the Jewish community. quagmire. For instance, if an Afghani Muslim who sympathized with Jewish persecution had directed Borat, the film would lose its satiric thrust simply because people would assume it was intended as derogatory. So while Cohen’s intentions are vital, his religious and ethnic identities are what make it possible for him to engage in such taboo dialogue. The full effectiveness of Cohen’s ethnic identity is demonstrated during Borat’s performance in the country-western bar. When Borat first takes the stage the crowd is skeptical of the Kazakh about to perform. By the time he cycles back through to the chorus of “Throw the Jew down the well, so my country can be free. You must grab him by the horns, then we have a big party,” the now boisterous crowd joins in, forming a spirited chorus of hate directed at a nameless Jew 9000 miles away. Borat begins the song as the only overt anti-Semite in the crowd. But as soon as Borat begins to sing, he awakens some dormant sentiment in the crowd. As McMorris notes, “By himself being anti-Semitic, [Borat] lets people lower their guard and expose their own prejudice, whether it’s anti-Semitism or an acceptance of anti-Semitism.”11 Cohen, referencing Ian Kershaw’s remark that ‘the path to Auschwitz was paved with indifference,’ explains, “it’s an interesting idea that not everyone in Germany had to be a raving anti-Semite. They just had to be apathetic.”12 Borat simply starts the song, and everyone follows — whether or not they harbor individual prejudices towards Jews is immaterial. The scene forces insightful viewers to reflect, then, not only upon their own prejudices toward Jews but also upon how Americans tend to tolerate prejudices and thereby provide fertile soil for intolerance. Satire’s salutary features notwithstanding, this form of didactic critique cannot be undertaken without intrinsic risk — namely, what happens if the audience doesn’t “get it”? McMorris raises this question when she comments (referencing the Anti-Defamation League’s statement) that “the audience may not always be sophisticated enough to get the joke,”13 and Low and Smith echo this concern by noting “the risk that the satire might actually back-fire.”14 This ADL released this statement in 2006 saying: We hope that everyone who chooses to see the film understands Mr. Cohen’s comedic technique, which is to use humour [sic] to unmask the absurd and irrational side of anti-Semitism and other phobias born of ignorance and fear. We are concerned however, that one serious pitfall is that the audience may not always be sophisticated enough to get the joke, and that some may even find it reinforcing their bigotry.15 If this is in fact the case, then religiously satirical works like Borat are not only rendered irrelevant but are, in fact, damaging to the inter-religious dialogues and tolerance they intend to catalyze. Another danger associated with ironic satire is its potential to “inflame bigotry further.” In other words, what happens if the audience actually identifies with those being parodied — in this case, the patrons of the bar — and as a result find their dormant racist sentiments aroused? What if the audience actually is bigoted? Vidamar and Rokeach argue for the pedagogical function of racist satire, stating that “mixing humour with bigotry releases tension, and this catharsis reduces prejudice.”16 However, if they’re wrong, films like Borat may actually make the prejudiced more prejudiced. While these trepidations are noteworthy, for the vast majority of audiences this form of parody effectively accomplishes its aim to “unmask the absurd.” Most educated viewers can’t help but come away from the film with a sense that the ridiculous nature of the movie ultimately points at something greater. This form of parody effectively accomplishes its aim to “unmask the absurd.” Most educated viewers can’t help but come away from the film with a sense that the ridiculous nature of the movie ultimately points at something greater. Sure, one could argue that theaters full of teenageguys laughing unabashedly and howling throughout some of the cruder moments of the film (the hairynaked wrestling scene in the hotel room, for example), suggest that Borat is nothing more than a crass comedy, whose outrageousness is intended primarily for shock value, rather than reeducation of racial prejudices. But even this audience comes away with a visceral reaction to the film — perhaps one they can’t articulate — which suggests that real anti-Semitism isn’t funny, and that’s why the movie is funny. Simply, the over-the-top anti-Semitism is just too ridiculous to be taken seriously, and if people don’t understand that they’re probably a lost cause anyway. 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid. 13 Ibid. 14 Low and Smith, “Borat,” 32. 15 Anti-Defamation League. Statement On The Comedy Of Sacha Baron Cohen, A.K.A. “Borat,” 28 September 2006, available from http://www.adl.org/PresRele/Mise_00/4898_00.htm; accessed August 8, 2010. 16 Low and Smith, “Borat” 32. 43 Exaggerated Satire in Saved! MGM In contrast with Borat, which exemplifies what Low and Smith label “ironic satire,” Saved! provides an illustration of what they deem “exaggerated satire.” This mode of satire tends to exaggerate stereotypes to the point of caricature. The result is a sort of hyper-magnification of the specific traits the satirist intends to ridicule, critique, or comment upon. However, while this strategic approach differs from the wry irony discussed above, the function is the same: it provokes an analogous form of reflection and evaluation of religious perceptions, biases and stereotypes, thereby providing the audience with a chance to “re-educate” themselves or reshape their perceptions and opinions. Saved! is set at the fictitious American Eagle High School, an über-conservative fundamentalist Christian school, presumably located somewhere within the Bible belt. Outside the school a massive representation of Jesus (over 20 feet tall) stands erected with its arms stretched out wide — ostensibly indicating the openness and loving-kindness of the Christian community that it symbolizes. Inside the school’s main auditorium, large placards which read “Love one another” and “Judge not and ye shall not be judged,” hang behind the stage. The audience immediately encounters the narrator and main character, Mary, as her voice seeps softly through the opening credits. “I’ve been born again my whole life… Accepting Jesus and getting salvation is a big decision, especially for a 3 year old.” While her still faceless voice speaks with conviction, the audience is struck by this peculiar phrasing. The audience next learns that Mary’s friend Hillary Faye, the primary subject of the film’s caricature, is the self-pro- claimed president of “the Christian Jewels,” an elite and exclusive clique who, even by the standards of American Eagle, are characterized by their “righteousness” (they even don gold pins to identify themselves!). Hillary Faye’s license plate reads “JCGIRL,” and on the opening day of classes she leads her classmates in a comically histrionic rendition of “Holy, Holy, Holy” complete with raised hands and synchronized swaying, which eventually devolves into cultish sounding chants of “Jesus rules! Jesus rules!” The drama begins when Hillary Faye’s best friend Mary — her name no doubt an allusion to the Blessed Virgin — finds out that her “perfect Christian boyfriend” Dean is gay. A devastated Mary irately asks God, “why has he been stricken with such a spiritually toxic affliction?” Hillary Faye remarks to Mary, “What if you had married him? The gayness would have been passed on to your children,” before resolving to start a “P-Circle” (prayer circle) for Dean’s “faggotry.” Mary, ironically, resolves to have sex with Dean to restore his heterosexuality, convinced that “You’re not born gay, you’re born again.” Of course, Mary gets pregnant from the encounter and Dean’s parents subsequently discover his secret and ship him away to Mercy House, a “degayification center” that also treats alcoholism and drug abuse. Mary is henceforth stripped of her title of “Christian Jewel” and castigated by the community (specifically by Hillary Faye). As this brief introduction to the film illustrates, much of the “exaggerated satire” is manifested in the rhetoric used by Hillary Faye and other members of the fundamentalist community. When Mary refers to Dean’s homosexuality as a “toxic affliction” and his parents send him to Mercy House, the film implies that being gay is tantamount to being an alcoholic or 44 a drug addict. In another scene, Mary prays that her pregnancy test comes back negative and that instead her symptoms can be attributed to cancer, as if that would somehow be a better alternative. In this way Saved! intends to shock, confuse, and even outrage its viewers. As I watched the scene I was incensed: Are there really people who are this hopelessly narrow? Mary would rather have cancer than have a child? Really? Still, though the attitudes of Hillary Faye and others like her may seem intolerant and antiquated to most, they would at least be defensible if it weren’t for the dissonance between Hillary Faye’s façade of “righteousness” and her actual behavior throughout the film. The real satiric sting comes not, then, from her “holier-than-thou” attitude, but rather how secular she appears when juxtaposed with other characters in the film. Her real crime is hypocrisy. In contrast to the compassionate posture of the oversized Jesus whose open arms overarch American Eagle, Hillary Faye is the first one to reject Mary when the students learn of her pregnancy. Unlike the Jesus who she claims to represent — a Jesus who let a prostitute bathe his feet — Hillary Faye closes her arms to her own best friend. In the climatic confrontation between the two, Mary challenges Hillary Faye that “You don’t know the first thing about love!” Hillary Faye responds by hurling a Bible at Mary’s head, shouting, “I am filled with Christ’s love!” In subsequent scenes Hillary Faye adheres to the archetypal image of “the popular girl” as portrayed in other secular “teen” films — snobby, catty, and condescending. In one scene she berates one of her “friends” for speaking out of turn — “Do you want to go back to being invisible girl with bad hair?” Film re viewer A.O. Scott writes that Hillary Faye is “a kind of mean girl for Jesus” and that “a religious high school is high school just the same.”17 In other words, while she is ostensibly a “perfect Christian,” she appears shockingly similar to her secular counterparts. If anything, some of the secular characters seem more “Christian” than HillaryFaye. For example, Cassandra Edelstein — the school’s only Jew — is one of only a few characters who remains loyal to Mary. Cumulatively, these images illustrate the inconsistency between fundamentalist rhetoric about “loving thy neighbor” and the manner in which some ultra-conservative Christian groups actually interact with society. Many are aware, for example, of fringe “Christian” groups who protest the funerals of fallen soldiers and the weddings of same sex couples, proclaiming God’s hatred for the involved individuals and predicting their everlasting damnation. While the characters in Saved! stop short of such vitriolic proclamations, the message within the satire is the same — namely, “how has the message of Christ become so contorted that his gospel is now being used for violence and hate?” The question evokes a famous remark by Gandhi; “I like your Christ; I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ.” The visceral lesson for most audiences might best be summarized by the concluding conversation between Pastor Skip, the school’s principle, and his skateboarding son Patrick who gradually evolves to ally himself with Mary and Cassandra. Pastor Skip: “This is not a gray area, Patrick. The Bible is black and white.” Patrick: “It’s all a gray area, dad” What Patrick conveys is that, as Scott writes, “religious morality should be tolerant of human fallibility and difference.”18 It is important to note that Patrick’s plea for moderation and compassionate sensitivity does not require an amorphous a-morality, nor does it preclude the audience from bringing discernment to bear upon questions concerning the Good. Such a reaction would confuse civility with ideological agreement, and sacrifice the opportunity for robust, rigorous, and potentially transformational dialogue within society and among various religious groups. Still, Patrick’s insight is correct in realizing that the strictest and most orthodox religious rhetoric risks becoming so polarizing to the secular world that it is rendered inaccessible and thereby irrelevant. Christians aren’t going to get anyone Saved! by preaching a message of intolerance and living lives of self-righteous hatred. Therefore, the film seems to say, regardless of the intellectual or theological beliefs held by certain religious groups, their policy for interacting with secularists and members of other Saved! intends to shock, confuse, and even outrage its viewers. As I watched the scene I was incensed: Are there really people who are this hopelessly narrow? Mary would rather have cancer than have a child? Really? 17 A.O. Scott, “In a Teenage Movie, a Religious High School is High School Just the Same,” New York Times, 28 May 2004, E13. 18 Ibid. 45 faiths must be dictated by values such as temperance, love, and a willingness to engage with civility in interfaith dialogues. Regardless of the intellectual or theological beliefs held by certain religious groups, their policy for interacting with secularists and members of other faiths must be dictated by values such as temperance, love, and a willingness to engage with civility in interfaith dialogues. Like the dangers associated with ironic satire, however, one must also be wary that exaggerated caricature, in an attempt to draw attention to the ridiculous, may lose some of its integrity in portraying a subject accurately. As Bridgman notes, “no one can be satisfied by generalizations on such a large subject.”19 Likewise, Elisha McIntyre notes that religious satire has a “tendency to see religious as synonymous with fundamentalist.”20 Of course, the two terms are not synonymous and there are many Christian groups — and Jewish groups, and Muslim groups — who value interpersonal and interfaith relations above exclusive and dogmatic interpretations of doctrine. In fact, most religious people are less concerned with orthodox teachings than they are with living out the broader values that these 19 Bridgman, “Satire’s Changing Target,” 85. 46 20 McIntyre, “Can True Love Wait?” creeds point to — such things as love, generosity, humility, acceptance, forgiveness, and charity. These qualities, which are widely practiced among adherents of all the world’s principle religions, tend not to be conspicuous or ostentatious in their application. It is the extremists who often skew our understanding and perception of religious groups. While there certainly are Hillary Faye’s flinging Bibles out there somewhere on the fringe, most Christians don’t bomb abortion clinics, and most Muslims don’t detonate explosives in their undergarments. The Trick Mirror — How Satire Helps Us See Things Anew Two conclusions emerge from these examinations of religious satire in film. First, satire does allow our culture to approach the taboo more candidly. Cohen’s backwards humor and the caricatures of Hillary Faye seamlessly draw audiences into dialogues which otherwise remain culturally “sticky.” It’s difficult to reflect on our cultural prejudices or the nature of our strict religious dogmas, but these films encourage deliberation on these themes in ways a less disarming cultural pulpit could not. Second, however, intentionally using inflammatory rhetoric of prejudice tends to entrench and harden opposing opinions and offend those who might not understand the use of satire as a tool. Exaggerated caricatures may lead to misrepresentations of, and misconceptions about, certain religious groups. These caricatures may ultimately result in propagating ignorance of their own, as well as offend the adherents of those sects. But maybe that’s exactly the point: If satire is indeed intended to be the The Offensive Art, as Leonard Freedman christened it, then perhaps offending is exactly what makes it so effective. Perhaps the offensive element of satire is in fact the element that allows satire to bypass the formalities of political correctness. Perhaps the offensive element provides a sort of grandiose misdirection — while the audience fixates on the outrageousness of the satire, the author’s pointed arguments are casually brought into focus, and the taboo is seamlessly integrated into the discussion. Sure, there will be casualties among those who can’t see past the offending blows, but the result for the majority is a unique sort of reflection that only satire can foster. Satire, like traditional film, holds a “mirror” up to our culture, but the image which satire provides is unique. Satire’s reflection resembles that of a trick-mirror. Yes, it reflects an image of our culture, our ideas, our perceptions, prejudices, beliefs and biases; but it does so in a refracted fashion. The trick mirror admittedly distorts certain elements, uses light to create illusions, and renders an image with parts disproportionately sized and not entirely believable. But by virtue of the distortion, wrinkles and blemishes that would otherwise escape scrutiny are brought into disturbing prominence. Satire thus provides us an opportunity, provided we can exercise the requisite discernment, to see ourselves with greater objectivity and transparency. And satire’s trickmirrors retain one particularly redeeming feature: if we don’t like the reflected image, we can change it by simply moving into a different posture. Bibliography Anti-Defamation League. Statement On The Comedy Of Sacha Baron Cohen, A.K.A. “Borat,” 28 September 2006, available from http://www. adl.org/PresRele/Mise_00/4898_00.htm; accessed August 8, 2010. Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan. Dir. Larry Charles. With Sacha Baron Cohen and Ken Davitian. 20th Century Fox, 2006. Bridgman, Richard. “Satire’s Changing Target.” College Composition and Communication 16.2 (1965): 85-89. http://jstor.org. Web. 29 Mar. 2010. Cowan, Douglas E. “South Park, Ridicule, and the Cultural Construction of Religious Rivalry.” Journal of Religion and Popular Culture 10 (2005), n.p. http://www.usask.ca/relst/jrpc/. Web. 29 Mar. 2010. Freedman, Leonard. The Offensive Art: Political Satire and its Censorship around the world from Beerbohm to Borat. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 2009. Hamner, Everett. “Damning Fundamentalism: Sinclair Lewis and the Trials of Fiction.” Modern Fiction Studies 55.2 (2009): 265-289. http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/modern_fiction_ studies/toc/mfs.55.2.html. Web. 29 Mar. 2010. The trick mirror admittedly distorts certain elements, uses light to create illusions, and renders an Low, Bronwen, and David Smith. “Borat and the Problem of Parody.” Taboo 11 (Spring-Summer 2007): 27-38. image with parts dispro- McIntyre, Elisha. “Can True Love Wait? Christian Morality Meets Adolescent Sexuality in Teen Film.” The Eternal Sunshine of the Academic Mind (2005): 65-72. entirely believable. But by McMorris, Christine M. “Borat’s Religious Provocations.” Religion in the News (Winter 2007): 19-21. Religulous. Dir. Larry Charles. Perf. Bill Maher, Steve Burg, Francis Collins. Lions Gate, 2008. DVD. Saved! Dir. Brian Dannelly. Perf. Mandy Moore. MGM, 2004. DVD. Scott, A.O. “In a Teenage Movie, a Religious High School is High School Just the Same.” New York Times, 28 May 2004: E13. portionately sized and not virtue of the distortion, wrinkles and blemishes that would otherwise escape scrutiny are brought into disturbing prominence. Swift, Jonathan. “A Modest Proposal.” In A Modest Proposal and Other Writings, Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Classics, 2009. Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Puffin Classics. New York: Puffin, 1995. Voltaire. Candide, or Optimism, Penguin Classics. London: Penguin Classics, 2006. 47