Article in PDF - University of Oklahoma

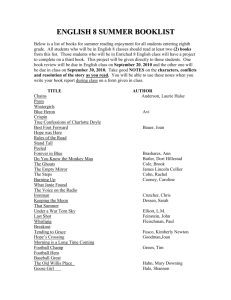

advertisement