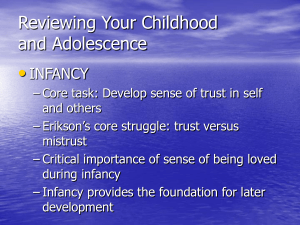

THE IMPACT OF ERIKSON'S INDUSTRY VS. INFERIORITY STAGE

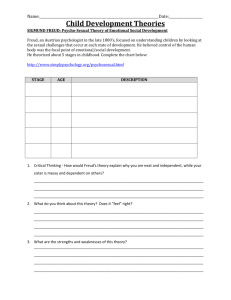

advertisement