The Economic Roles of Agriculture in Developing Countries

advertisement

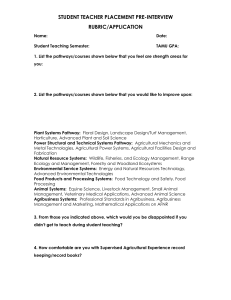

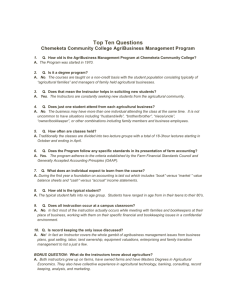

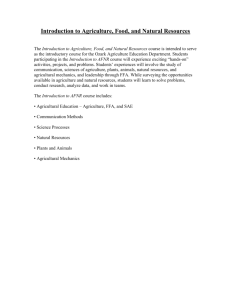

Discussion Paper No. 0118 How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles of agriculture in development? Randy Stringer May 2001 Adelaide University SA 5005, AUSTRALIA CENTRE FOR INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC STUDIES The Centre was established in 1989 by the Economics Department of the Adelaide University to strengthen teaching and research in the field of international economics and closely related disciplines. Its specific objectives are: • to promote individual and group research by scholars within and outside the Adelaide University • to strengthen undergraduate and post-graduate education in this field • to provide shorter training programs in Australia and elsewhere • to conduct seminars, workshops and conferences for academics and for the wider community • to publish and promote research results • to provide specialised consulting services • to improve public understanding of international economic issues, especially among policy makers and shapers Both theoretical and empirical, policy-oriented studies are emphasised, with a particular focus on developments within, or of relevance to, the Asia-Pacific region. The Centre’s Executive Director is Professor Kym Anderson (Email kym.anderson@adelaide.edu.au) and Deputy Director, Dr Randy Stringer (Email randy.stringer@adelaide.edu.au). Further details and a list of publications are available from: Executive Assistant CIES School of Economics Adelaide University SA 5005 AUSTRALIA Telephone: (+61 8) 8303 5672 Facsimile: (+61 8) 8223 1460 Email: cies@adelaide.edu.au Most publications can be downloaded from our Home page at http://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/ ISSN 1445-3746 series, electronic publication CIES DISCUSSION PAPER 0118 How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles of agriculture in development? Randy Stringer School of Economics and Centre for International Economic Studies University of Adelaide Adelaide SA 5005 Phone + 61 8 8303 4821 randy.stringer@adelaide.edu.au May 2001 Copyright 2001 Randy Stringer ________________________________________________________________________ This paper has been prepared for FAO’s ESAC Research Project, Socio-Economic Analysis and Policy Implications of the Roles of Agriculture in Developing Countries. The paper was presented at the 19--21 March 2001 Consultation in Rome. Thanks due to the discussants for helpful suggestions and comments, including J. Mellor, R. Pertev, K. Stamoulis and A. Valdés. Responsibility remains with the author. All the papers may be accessed via FAO’s web site: www.fao.org. ABSTRACT How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles of agriculture in development? Randy Stringer Some good reasons explain why early approaches to identifying agriculture’s economic roles resulted in a one-way strategic path that involved the flow of resources towards the industrial sector and urban centres. In an effort to provide a more comprehensive view of the roles that agriculture plays in promoting human well-being, FAO initiated the Role of Agriculture Project (ROA) to provide a new approach to poverty alleviation and socioeconomic development. The purpose of this report is to present examples, suggestions, and possible methods and tools on how to document, measure and identify the functions and values of the ‘nontraditional’ economic roles that agriculture plays in the development process. The report’s immediate aim is to provide a basis for discussion during the ‘Economic Roles of Agriculture’ session at the 19-21 March, consultation in Rome. The intent here is to provoke discussion, rather than to capture all of the issues and details that merit analysis. The paper presents examples to initiate the discussion and allow participants to add substance, refine concepts and alter, delete and adapt the analytical framework as appropriate. Six of the contributions listed in Figure 1 are outlined in some detail. Other examples may be discussed during the consultation together with those suggested by participants. The six examples are agriculture’s economic contributions: (i) to agribusiness activities not usually considered part of the agricultural sector; (ii) as social welfare infrastructure; (iii) through rapid productivity growth; (iv) to alleviating poverty; (v) to learning and education; and (vi) to healthy and safe food. The remainder of the paper suggests alternative methodologies, identifies various indicators and presents ways to measure their economic importance. Using both qualitative and quantitative methods to capture non traditional economic roles is suggested to help understand the various functions, benefits and values . A narrative approach would involve analyzing: the economic roles of agriculture in contributing to agribusiness, local trade and service firms, and the social structure of rural communities; the likely influence of new technology and economic stress on the organization and control of agricultural resources; the relative importance of agriculture in the economic base of rural areas; competition for resources between agriculture and other components of the rural economy, and the importance of off-farm employment and income for farm families. Contact author(s): Randy stringer School of Economics and Centre for International Economic Studies University of Adelaide Adelaide SA 5005 Phone + 61 8 8303 4821 randy.stringer@adelaide.edu.au How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles of agriculture in development? Randy Stringer Introduction and Overview Long before Johnston and Mellor (1961) identified what are today considered the fundamental economic contributions of agriculture to development, economists focused on how agriculture could best contribute to overall growth and moderization. Many of these earlier analysts (Rosenstein-Rodan, 1943; Lewis, 1954; Scitovsky, 1954; Hirschman, 1958; Jorgenson, 1961; and Fei and Ranis, 1961) highlighted agriculture for its many resource abundances and its ability to transfer surpluses to the more important industrial sector. By serving as the ‘handmaiden’ to the industrial sector, agriculture’s primary role in the transformation of a developing economy was seen as subordinate in the central strategy of accelerating the pace of industrialization. As Vogel (1994) notes, Hirschman singled out agriculture for its failure to exhibit the strong forward and backward interindustry linkages needed for development. Hirschman (1958) argued that, ‘…agriculture certainly stands convicted on the count of its lack of direct stimulus to the setting up of new activities through linkage effects: the superiority of manufacturing is crushing’. Over time, a traditional approach to development emerged that concentrated on agriculture’s important market-mediated linkages. Several core economic roles for agriculture formed this traditional approach: (1) provide labour for an urbanized industrial work force; (2) produce food for expanding populations with higher incomes; (3) supply savings for industrial investments; (4) enlarge markets for industrial output; (5) earn export earnings to pay for imported capital goods; and (6) produce primary materials for agro processing industries (Johnston and Mellor, 1961; Ranis et al 1990; Delgado et al, 1994; Timmer, 1995). In an effort to provide a more comprehensive view of the roles that agriculture plays in promoting human well-being, FAO initiated the Role of Agriculture Project (ROA) to provide a new approach to poverty alleviation and socio-economic development. The objectives of ROA include providing policy makers with insights and tools for informing policy options concerning the diverse roles of agriculture in the context of greater and more sustainable development; producing a common analytical framework and valuation tools, as well as in-depth documentation from country case studies; and creating awareness and general appreciation of the diverse roles of agriculture in society and how their nature, magnitude, and policy implications vary by farming system, country setting, and through time (FAO, 2001). The purpose of this draft report is to present examples, suggestions, advice, methods and tools on how to document, measure and identify values of the ‘non-traditional’ economic roles agriculture plays in the development process. The report’s immediate aim is to provide a basis for discussion during the ‘Economic Roles of Agriculture’ session at the 19-21 March, consultation in Rome. The intent here is to provoke discussion, rather than to capture all of the issues and details that merit analysis. More specifically, the aim of this discussion paper is to suggest answers to the following questions: (1) What are the key conceptual issues to be addressed in devising an approach for defining and measuring the non-secular economic impacts of agriculture? (2) What has been done so far to study and address these issues? (3) Once the issues have been identified, how analytical framework derives from the issues identified? (3) What types of indicators could be used or possibly developed to measure and compare the non-secular economic outputs of agriculture? What do we mean by agriculture’s non-traditional economic roles? Some good reasons explain why early approaches to identifying agriculture’s economic roles resulted in a one way path that involved the flow of resources towards the industrial sector and urban centres. In agrarian societies with few trading opportunities, most resources are devoted to the provision of food. Agriculture’s shares of national output and employment therefore start at high levels. As economic development proceeds, agriculture’s shares of GDP and employment typically fall. This is commonly attributed to the slow rise in the demand for food as compared with other goods and services as incomes rise; and the more rapid development of new technologies for agriculture, relative to those for other sectors, which leads to expanding food supplies per hectare and per worker. A third but less-commonly recognized phenomenon contributing to agriculture's relative decline is the rapid growth in modernizing economies in the use of intermediate inputs purchased from other sectors (Anderson, 2000a). This decline in agriculture’s GDP share results partly because post-farm gate activities (such as taking produce to market becomes commercialized and taken over by specialists in the service sector) and partly because producers substitute chemicals and machines for labour. Producers receive a lower price and in return for which their households spend less time marketing. As a result, value added by the farm household's own labour, land and capital, as a share of the gross value of agricultural output, falls over time as purchased intermediate inputs become more important. This increasing use of purchased intermediate inputs and off-farm services by farmers adds to the relative decline of the producing agricultural sector per se in overall GDP and employment (Timmer 1988, 1997; Pingali, 1997). Agriculture’s declining share in the economy sends a confusing signal to policymakers that agriculture is relatively unimportant. And the falling real prices of agricultural commodities sends the signal to investors that returns are relatively unattractive (Tyers and Anderson, 1992) A number of development economists attempted to point that while agriculture’s share fell relative to industry and services, it nevertheless grew in absolute terms, evolving increasingly complex linkages to the non-agricultural sectors. This group of economists (including Kuznets 1968; Kalecki, 1971; Mellor, 1976; Singer, 1979; Adelman, 1984; de Janvry, 1984; Ranis, 1984; and Vogel, 1994, to name a few) highlighted the interdependence between agricultural and industrial development and the potential for agriculture to stimulate industrialization. They argue that agriculture’s productive and institutional links with the rest of the economy produce demand incentives (rural household consumer demand) and supply incentives (agricultural goods without rising prices) promoting modernization. This broader approach to the economic roles of agriculture suggested that the one-way path leading resources out of the rural communities ignored the full growth potential of their agricultural sectors. A two-way path was needed. Resources still must move towards industry and urban centres, but with attention focused on the capital, technological, human resource and income needs of agriculture. This required policymakers to change strategies. Traditional macroeconomic policies that inhibited rural sector growth through direct and indirect taxation of food producers, traders and exporters would need to give way to a more a non-discriminatory policy environment for agriculture (Krueger et al, 1991; Bautista and Valdés, 1993); investments in producing technological innovations (Hayami and Ruttan, 1971; Pinstrup-Anderson, 1994; Oram, 1995); and public investments in rural incomes generating social and physical infrastructure (Adelman, 1984; Vogel, 1994). One aim of the ROA project is to extend our current thinking about the economic roles of agriculture further. In particular, to identify those economic contributions for which the market prices of agricultural activities fail to convey enough information to secure an optimal level of those activities. (Environmental goods and services as well food security contributions are addressed in a separate report to be presented at the consultation. See Cooper, 2001 and Lee, 2001. FAO’s web site www.fao.org.) Agriculture’s under-recognised, non-traditional economic roles Figure 1 provides one way to map out a conceptual approach to the non-traditional economic roles of agriculture. Beginning on the left hand side, the traditional economic roles are listed as direct use contributions. Moving to the right, the next set of contributions represent what are more commonly know as agribusiness activities, followed by externalities and public goods on the right hand side. This mapping offers an approach to introducing and defining the non traditional economic roles of agriculture. The importance and weight attached to a given role varies between and within countries, depending on their particular situation and national priorities. These various functions and benefits are valued differently by different people and different groups. Local, national and international interests in agriculture’s economic roles also differ greatly across landscapes. Moreover, the roles that agriculture is expected to play in local, national, and global development change over time. Agriculture’s economic contributions to agribusiness activities While classified as direct contributions and easily measurable, the many economic activities of agribusiness are often ignored by governments and policymakers. A large and increasing part of economic growth during the process of development can be attributed to those activities that support the production, marketing, and retailing of food, textiles, clothing, shoes, tobacco, beverages, and related good for both domestic consumers and exports. Over time, primary agriculture gives up the processing, storing, merchandising, transporting, and financing practices, giving way to a more complex, specialised and integrated process. A long, circular chain evolves. Input providers, farm suppliers, assemblers, processors, wholesalers, brokers, importers, exporters, retailers, merchants, distributors, and consumers join the food and agricultural economic links. Additional activities continually service these businesses, including research, transportation, packaging, storage, futures markets, advertising and promotion (Davis and Goldberg, 1957; Newman, et. al. 1989; Holt and Pryor, 1989; FAO, 1997). All these agribusiness activities are totally dependent on primary production. Primary production grows and evolves reflecting agribusiness, and agribusiness grows and evolves reflecting primary production. They are inextricably connected. Ignoring the large economic contributions of primary agriculture to these much faster growing agribusiness activities presents an incomplete picture of their shared world. Take for example, how much more agricultural commodities are used as inputs into food processing in the industrial countries. In Argentina, Brazil, Korea Republic and the USA, more than 60 percent of total agricultural output is used as an input into further economic activity. Contrast this with India, where more than two thirds is consumed directly (Holyt and Pryor, 1999). Likewise, the more developed agricultural economies depend on more power, machinery and agro-services. In India, some 70 percent of the total cost of processed rice is paddy rice. In the USA, the rice is less than 6 percent of the total cost (Holyt and Pryor, 1999). While the share of service-related input costs in the USA is more than 20 percent, in Mexico and the Philippines it is less than 1 percent. The overall importance of agribusiness as a share of total GDP is seen in Table 1. These linkages may form an important part of the ROA project, providing easily measurable contributions. In addition, the associated agribusiness industries and firms provide a ready made interest group able to lobby, argue and articulate the economic importance of primary producers. Agriculture’s economic contributions as social welfare infrastructure Moving further to the right in Figure 1 are a number of economic roles that are provided by agriculture as semi-externalities or public goods. These are functions which may not exist without agricultural production, but which producers are not compensated. For instance, agriculture provides a number of welfare enhancing, ‘income’ transfer and income-shock buffer functions. For instance, a recession or externally-induced income shock or financial crisis affects households differently, varying across sector of employment, level of wealth, geographic location, gender, and various other factors. Household and community welfare is effected through changes in relative prices, in aggregate labour demand, in the rates of returns on assets, changes in public transfers, and in the community environment --in terms of public health or public safety (Ferreira, 1999). During a crisis, agriculture can act as a buffer, safety net, and as an economic stabiliser (FAO, 2001). In this way, the agriculture sector can provide a substitute for a welfare system in those countries unable to provide unemployment insurance or other types of social services for retiring workers and employees who lose their jobs during structural change or income shocks. Because primary agriculture tends to be relatively flexible regarding both the scale of operations and technology, some of the non-agricultural unemployment caused by a severe income shock can be re-absorbed into agricultural activities. Agriculture tends to provide a much wider range of substitutability among factors of production especially labour and capital, than is the case in much of industry. This social welfare role often acts as the most important buffer between ‘poverty’ and full blown chronic undernutrition. Thus this buffer role of agriculture keeps income distribution within reasonable bounds to help ensure that some of the poor do not fall below the nutrition threshold. In addition, agriculture operates as important social welfare infrastructure in remote locations, creating development opportunities and producing basic necessities for isolated communities. Agriculture provides basic subsistence occupations for millions and permits people to supply themselves with the three fundamental human needs: food, clothing and shelter. National accounting measures too often fail to reflect the true value of this production and capital creation within agriculture because much of it does not enter the market as monetized values. Consequently, agriculture is often downgraded and under recognized. In a similar vein, agricultural workers bear many of the costs of structural change during times of strong economic growth. If rural producers are to share in the benefits of growth, many must leave the countryside and farming. If there were no reduction in farm employment as economic growth occurs, most of the gains would not be realized. For example, if primary production employment in the Australia, Canada, the EU and the US were as high today as it was thirty years ago, the income earned in farming would be far less. Migrations costs are borne by the migrants, including the actual cost of moving, finding a job, locating housing, and the psychological costs of leaving familiar conditions for conditions that are strange and, in some ways, threatening (Johnston, 1998). Agriculture’s economic contribution through rapid productivity growth Over time, agriculture remains more productive than industry so the real price of food declines, contributing to: increased savings; increased incomes; economic stability; and overall total factor productivity. Historically, agricultural productivity growth has been even faster than productivity growth in manufacturing. Farm productivity growth in the agricultural-exporting rich countries has been comparatively very rapid. In the United States, for example, total factor productivity growth since the late 1940s has been nearly four times as fast in farming as in the private non-farm sectors (Jorgenson and Gollop 1992), and similar performances have been found in Australia and Canada (Martin and Mitra, 1998). As well, new technologies are capable of making food safer and raising its quality, and of reducing any harm to the environment caused by farming. These properties are valued more and more as people's incomes grow and as the natural environment comes under stress. In low-income countries where people spend a high proportion of their income on food, even small food price increases can be detrimental to the well-being of the urban poor and rural net-food purchasers. Many of the poorest people in low-income countries also depend on agriculture (directly and indirectly) for their livelihoods, and rising crop prices may actually increase their real incomes and food intake. Agriculture’s economic contribution to alleviating poverty Past evidence suggests that periods of high agricultural growth rates are associated with falling rural poverty (Binswanger and von Braun, 1991; Timmer, 1992; Bell and Rich, 1994; Johnson, 1998; Mellor, 2001). Strong agricultural growth leads to: (1) lower food prices (for urban consumers and rural net-food buyers); (2) increased income generating opportunities for food producers and jobs for rural workers (thus reducing rural-urban migration, with positive consequences for real urban wage rates); and (3) positive intersectoral spillover effects including migration, trade and enhanced productivity (Lipton and Ravallion, 1995; Timmer, 1992). A World Bank review concludes that higher agricultural and rural growth rates are likely to have a ‘strong, immediate, and favourable impact’ on poverty (World Bank 1996). The review notes that agricultural growth rates exceeding 3 percent a year produce a decline in the World Bank’s poverty index grouping by more than 1 percent. In no case did poverty decline when agricultural growth was less than 1 percent (World Bank 1996). Even the most populated countries have had great success. In both China and Indonesia, for example, rapid agricultural growth substantially reduced rural poverty, improved food security in both rural and urban sectors, and provided a significant demand side stimulus for non-agricultural goods and services. No country has been able to sustain the process of rapid economic growth without solving its problems of marcro food security (Timmer et al, 1983; World Bank, 1996). In contrast, countries failing to make progress in agricultural growth experience stagnating rural sectors, sluggish overall economic growth with declining per caput incomes, and falling investment in rural services and agricultural infrastructure (Binswanger and Landell-Mills 1995; FAO 1996). In addition, while rural growth has important impacts on urban poverty reduction, urban growth has much less impact on urban poverty reduction (Mellor, 2001). Agriculture’s economic contribution to labour productivity through education Agriculture’s role in providing jobs, income and food contribute indirectly to education which in turn provide private and public benefits. The better the education, the more opportunities for a higher-paying job and the ability to be well-nourished and to work more, earn more, consume more and save more. Agriculture contributes to these increased incomes by enhancing food security (production and access via increased incomes). As incomes increase for subsistence and other rural households, families increasingly spend to educate their children. Thus rural households contribute to the overall education and productivity levels of those children who migrate to cities. Improving access to food increases learning capacity and school performance and leads to longer school attendance, fewer school (and work days) lost to sickness, higher earnings, longer work lives and a more productive work force. These are essential to economic growth. And economic growth is essential for increasing incomes and reducing poverty. The manner in which development strategies achieve growth, however, and the number of people who participate in and benefit from it are as important as the growth itself. In contrast, chronic malnutrition kills, blinds, and otherwise debilitates, reducing physical capacity, lowering productivity, stunting growth, and inhibiting learning. In the world’s poorest regions and countries, one-third of deaths among children are due to malnutrition (Del Rosso 1992). Improving access to food and nutrition increases learning capacity and school performance and leads to longer school attendance, fewer school and work days lost to sickness, higher earnings, longer work lives and a more productive work force. Markets frequently do not reflect the social value of education, research and training. Agriculture contributes indirectly to education and education is a classic example where the benefits of increased education to society are higher than the benefits of that education to an individual. In the case of women, the social returns to investment in education are higher still. Investing in human capital remains one of the most important keys to reduce poverty and bring about sustainable economic growth. Few measures contribute more to economic development and poverty alleviation than investing in women (World Bank, 1990; Kaito, 1994). Education, training and access to information are directly linked to productivity and aggregate output. A study of the determinants of real GDP covering 58 countries during 1960-85 suggests that an increase of one year in average years of education may lead to a three percent rise in GDP (World Bank, 1990). Virtually all studies on agricultural productivity show that better educated farmers get a higher return on their land. According to one study, African farmers who have completed four years of education - the minimum for achieving literacy - produce, on average, about 8 percent more than farmers who have not gone to school. Studies in Malaysia, Republic of Korea and Thailand confirm that schooling substantially raises farm productivity (World Bank, 1990). A World Bank study estimates that the rate of return on investments in women’s education is of the order of 12 percent in terms of increased productivity (Kaito, 1994). If women and men received the same education, says the study, farm-specific yields would increase from seven percent to 22 percent. Increasing women’s primary schooling alone would increase agricultural output by 24 percent (Kaito, 1994). Women’s education also typically pays off in wage increases, with a consequential rise in household incomes. According to a recent ILO report, each additional year of schooling has been shown to raise a woman’s earnings by about 15 percent compared with 11 percent for a man (Lim, 1996). Female education also has major social returns, contributing to improved household health and welfare, lower infant and child mortality, and slower population growth (Subbarao and Raney, 1995). Agriculture’s economic contributions to health and food safety Food consumers, whether motivated by green concerns or by concerns for health and food safety, are increasingly interested in where food comes from and how it is produced, processed, packaged and distributed. These health and food safety issues, (together with environmental quality) are often equated to superior goods, helping to explain why national preferences for private versus public goods consumption is a key factor influencing production, consumption and trade patterns. Relatively high-income economies have low income elasticity of demand for goods and services related to sustenance and it declines as income continue to rise. On the other hand, the income elasticity of demand for more environmental amenities is high and continues to rise. This stands is in sharp contrast to poorer countries where the income elasticity of demand is high for sustenance and low for environmental amenities. Empirical studies confirm these trends. While economic growth involves increased pollution associated with production and consumption, rising per capita incomes mean that societies demand more environmental quality and more income is available to protect environmental services (World Bank, 1992; Seldon and Song, 1994; Grossman and Krueger, 1995; and Hettige, et. al. 1998). This does not imply, however, that lower-income countries desire environmental quality less or have a low income elasticity of demand for environmental amenities, nor that income elasticity rises inexorably with income. But it is consistent with the fact that people in relatively wealthy countries have greater capacity to pay for more of everything, including higher environmental quality (Anderson, 1992; Stringer and Anderson, 1999). Like environmental goods, consumer demand for quality attributes in general and for food safety in particular are superior goods. Demand increases faster with income than does demand for food in terms of quantity. Consumers in wealthier countries demonstrate an increasing interest in food characteristics which go beyond nutritional properties and which respond to three types of utility: health, pleasure and ethics (Mahé and Ortalo-Magné, 1998). Pleasure is essentially a private goods. Consumers derive satisfaction related to the hedonistic characteristics of the product itself. Health and safety have both private and public good aspects. Ethics suggests utility can be affected by production and processing methods. The recent problems with BSE and with foot and mouth disease in the EU highlight the private and public values of animal health and safe food, including the costs associated with not supplying it. What has been done so far to study and address these issues? The references in the six issues presented above show only a small fraction of the available documentation for these types of non-traditional economic benefits. Most countries being considered for analysis in the ROA would have large literatures to draw on. Few studies, however, provide a big picture overview which enables synthesis and comparisons (the aim of the ROA). An exception is recent research motivated by ‘non-trade’ concerns with respect to agriculture and the environment acknowledge the fact that agriculture pollutes, but that agriculture can contribute simultaneously in positive ways to the environment (OECD, 1997). A series of studies emerged from these issues to identify various nonproduction benefits now commonly called multifunctionality (See Runge, 1999; and Anderson 200b for important examples). The issue of multifunctionality is not a new one, but it has attracted more attention in recent years. In addition to OECD, the WTO Committee on Agriculture highlights that some agricultural functions: (1) often have public goods characteristics; (ii) are often specific to the agricultural sector; and (iii) are to a large extent provided as joint products of the agricultural production activity itself. Some WTO member countries have suggested specific examples, including agriculture’s contribution to food security, the viability and development of rural areas, cultural heritage, the agricultural landscape, agro-biological diversity, land conservation and a healthy plant, animal and people (Norway, 1999). The question concerning a multifunctional agriculture has resulted in debate over whether multifunctionality should be rejected or accepted as a reason for protecting domestic agricultural production. The joint production relationship is complex and may relate both to certain types of input use, farming practices and technologies, and agricultural output, as well as a combination of all these elements. For instance, an authentic agricultural landscape cannot be provided without agricultural production activity. Moreover, as part of a country’s long-term food security, a certain degree of domestic food production may be judged as essential (Norway, 1999; Timmer, 1995). Timmer (1995) makes several points regarding how markets fail to provide incentives for agriculture’s non-production benefits. First, international prices do not reflect the importance attached by most countries to maintaining food security. Second, agriculture plays a special role in alleviating poverty in most Third World nations. Third, market prices for agricultural commodities undervalue the indirect effects of agricultural growth on providing resources for overall investment and for increasing overall total factor productivity. Fourth, governments need to learn how to make a market economy work and the agricultural sector offers an ideal environment within which learning by doing can effectively occur. How do we capture, measure and promote agriculture’s economic roles? Agriculture is related to the nonfarm rural sector, the urban sector, and the rest of the world in complex relationships that continually evolve. The output of agriculture is not homogeneous. It consists of many different products, goods and services that are used as food, as raw materials by industry, as exports, as social infrastructure, as productivity enhancing nutrition, as rural amenities and other related non commodity specific benefits. The policy implication of the earlier conception of agriculture as handmaiden to industry was straightforward. An understanding of the diverse nature of agriculture’s economic contributions involves recognizing its many linkages and their dynamic effects on rising incomes, overall development, urban migration, poverty, nonagricultural growth, wealth and income distribution, as well as how agricultural, nonagricultural, macroeconomic, and trade policies influence agricultural growth and linkages. The conceptual approach to analyzing the economic roles of agriculture presented in Figure 1 suggest first measuring the direct, non-traditional economic roles of agriculture. A qualitative and quantitative approach to non traditional economic roles may be useful to help capture the various functions, benefits and values . A narrative approach would involve analyzing the economic roles of agriculture in contributing to agribusiness, local trade and service firms, and the social structure of rural communities; the likely influence of new technology and economic stress on the organization and control of agricultural resources; the relative importance of agriculture in the economic base of rural areas, competition for resources between agriculture and other components of the rural economy, with emphasis on land use changes on the urban fringe, competing demands for natural resources (eg water in arid regions), and competition for labour resources between agriculture and other rural activities; and the importance of off-farm employment and income for farm families (SOFA, 1997). A social accounting matrix (SAM) provides a straightforward way to explore how agricultural sectors generate the direct use of non-traditional contributions (Figure 1) to overall economy. SAMs summarizes aggregate structural interrelationships among the various agents in an economy by mapping the circular flows of income and expenditures, and supply of goods and services. SAM entries represents the payment by one account to another account for services rendered or goods supplied. It can also represent an income transfer for jobs. SAM data requirements are not problematic for most developing countries. In addition, a great deal of information can be obtained from the Global Trade Analysis Project (GTAP) data base. For example, GTAP offers the ability to look at land: (a) land, labour and capital; (b) processed agricultural goods; (c) non agricultural inputs used by agriculture; (d) agricultural goods used for the production of other agricultural goods (e) agricultural outputs used by non agricultural sectors as inputs; (f) domestic consumption; and (g) exports. These data present a host of opportunities for analyzing the sector’s non traditional, direct contributions. One issue with GTAP will be the availability and the quality of country data from Africa. The upcoming version, GTAP V5, due out in April should provide an improved data base over past years. Identifying and measuring the indirect economic contributions are difficult and present a number of well-known issues. It may be useful in some countries, to take a specific public goods or externalities (the outputs, or lost potential of that output) and attempt to measure its value with accessible market valuation techniques. For example, value added and labour measurements (eg contribution to rural viability via tourism); production function or human capital techniques (eg productivity increases via improved education outcomes); replacement cost techniques (eg social welfare infrastructure substitute and poverty reduction potential). Some additional issues for discussion An important issue is not to over generalize about agriculture's role. National differences conceal great disparities in agricultural structure, the relative importance of agricultural to the rural economy and national development, resource use conflicts and the prevalence of off-farm employment, both among regions and among farm types. Since tastes and preferences change over time and differ between countries, so too will society’s valuation of those non-marketed products. And as technologies, institutions, policy experiences and market sizes change in the process of development, so does the scope for being able to market some of those previously unmarketable products that were jointly produced with each sector’s main products Every productive sector generates both marketed and non-marketed products. Some of those non-marketed products are considered more desirable than others, and some are considered undesirable. Anderson (2000) raises important policy questions related to agriculture’s non-market contributions. Is agricultural production a net contributor in terms of externalities and public goods? And is it more of a net contributor than other sectors and especially the sectors that would expand if agricultural supports were to shrink? Demonstrating that is an almost impossible task, given the difficulties in obtaining estimates of society’s ever-changing (a) evaluation of the myriad externalities and public goods generated by the economy’s various sectors and (b) marginal costs of their provision. All market failures associated with agriculture in the developed countries are replicated in the developing ones, but the incapacity to intervene effectively to regulate is even more evident and more problematic. Gardner (2001) points out several of the long standing controversial issues in the interlinked causes and effects of economic growth of agriculture that may be important for ROA policy development. The list includes: (a) understanding the sources of improvements in technology; (b) explaining the adoption of new technology; (c) understanding the reasons for changes in the economic organization of farm enterprises; (d) the economic consequences of technological and organizational change, particularly the effects on agricultural productivity, farm size, and income distribution; (e) the role of market integration between the farm and nonfarm economies, particularly with respect to labour markets -- both migration off farms and nonfarm sources of income for people who remain on farms; and (f) the role of government, and more generally, economic incentives, in fostering the creation and adoption of new technology and the development of changes in the economic organization of agriculture (Gardner, 2001). References Anderson, K. (2000a). ‘Towards and APEC Food System’, Report prepared for New Zealand's Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Wellington, February 2000. Since published on New Zealand government's web site at http://www.mfat.govt.nz/images/apecfood.pdf. Anderson, Kym, (2000b) ‘Mulifunctionality' and the WTO’, Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics, 44(3): 475-96. Adelman, I. (1984). ‘Beyond Export-Led Growth’. World Development, 12, 9, 937-49. Bautista, R. and A. Valdés. (1993). The Bias against Agriculture: Trade and Macroeconomic Policies in Developing Countries, San Francisco: ICS Press. Bell, C. and R. Rich. (1994). ‘Rural Poverty and Agricultural Performance in PostIndependence India’, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 56(2), pp., 111133. Binswanger, H.P. and von Brahn, 1991, ‘Technological Change and Commercialization in Agriculture: The Effect on the Poor’, World Bank Research Observer; 6(1), January 1991, pp. 57-80. Binswanger, H.P. and P. Landell-Mills. (1995) ‘The World Bank’s Strategy for Reducing Poverty and Hunger.’ Environmentally Sustainable Development Studies and Monographs Series No. 4. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank. Cooper, J. (2001) The Environmental Roles of Agriculture in Developing Countries. Paper prepared for FAO consultation on the Roles of Agriculture in Development, 19-21 March 2001, Rome. Davis, John and Goldberg, Ray. A Concept of Agribusiness. (1957). Chapter 3: ‘Agribusiness and Input-Output Economics’ de Janvry, A. (1984). ‘Searching for Styles of Development: Lessons from Latin America and Implications for India’, Working Paper No. 357, Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics, University of California, Berkeley. Delgado, C. et al. (1994). Agricultural Growth Linkages in Sub-Saharan Africa, Washington D.C.: US Agency for International Development. Del Rosso, H. (1992). “Investing in Nutrition with World Bank Assistance”, Washington D.C.: World Bank. FAO (1996). Food Agriculture and Food Security, The Global Dimension”, WFS96/Tech/1. Rome: FAO. FAO (1997). ‘The agroprocessing industry and economic development’, SOFA Special Chapter, FAO: Rome. Fei, J. C. and Ranis, G. (1961). ’A Theory of Economic Development’, American Economic Review, 51, 4, 533--65. Ferreira, F., G. Prennushi and M. Ravallion. ( ) Protecting the Poor from Macroeconomic Shocks: An Agenda for action in a crisis and beyond World Bank, Washington, DC. Gardner, B. (2001) How U.S. Agriculture Learned to Grow: Causes and Consequences, Allan Lloyd Address, AARES 2001 Conference, Adelaide. Grossman, G.M. and A.B. Krueger. 1995. “Economic Growth and the Environment,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 110(2): 353-377, May. Hayami, Y. and V. Ruttan. (1971). Agricultural Development: An International Perspective, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Hettige, H., M. Mani and D. Wheeler. 1998. "Industrial Pollution in Economic Development (Kuznets Revisited)" Paper presented at a World Bank conference on Trade, Global Policy and the Environment, Washington, D.C., 21-22 April Hirschman, A. O. (1958). The Strategy of Economic Development, Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut. In Developing Countries, Washington D.C. Johnson D. Gale. (1998). China's rural and agricultural reforms in perspective, Paper prepared for presentation at the Land Tenure, Land Market, and Productivity in Rural China Workshop, Beijing May 15-16. Johnson, D. Gale. (1998). ‘Food Security and World Trade Prospects’, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, Vol 80, No. 5, pp. 941-947. Johnston, B.F., and J.W. Mellor. (1961). "The Role of Agriculture in Economic Development." Amer. Econ. Rev. 51, September, pp. 566-93. Jorgenson, D. G. (1961). ’The Development of a Dual Economy’, Economic Journal, 71, 309--34. Jorgenson, D.W. and F.M. Gollop. (1992). 'Productivity Growth and US Agriculture: A Postwar Perspective', American Journal of Agricultural Economics 74(3): 745-56, August. Kalecki, M. (1971). Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy 1933-1970, Cambridge University Press: London. Kureger, A.O., M. Schiff and A.. Valdes. (1991). ‘Agricultural Incentives In Developing Countries: Measuring the Effects of Sectoral and Economy Wide Policies’, World Bank Economic Review, 2, pp. 255-271. Kuznets, S. (1968). Toward a Theory of Economic Growth with Reflections on the Economic Growth of Nations, Norton, New York. Lee, K. (2001) The Food Security Roles of Agriculture in Development. Paper prepared for FAO consultation on the Roles of Agriculture in Development, 19-21 March 2001, Rome. Lewis, W.A. (1954). ‘Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour’, Manchester School of Economics, 20, 139-91. Lim, Lin. (1996). ‘Women Swell Ranks of Working Poor’, World of Work, Vol 17, Geneva: ILO. Lipton, M. and M. Ravallion. (1995). ‘Poverty and Policy.’ In J. Behrman and T.N. Srinivasan, eds., Handbook of Development Economics Vol IIIB, Amsterdam: Elsevier Science B.V. Mahé L.P. and F. Ortalo-Magné. (1998). International co-operation in the regulation of food quality and safety attributes, OECD Workshop on Emerging Trade Issues in Agriculture Emerging Trade Issues in Agriculture to be held in Paris 26-27 October 1998, OECD: Paris. Martin, W. and D. Mitra (1998). ‘Productivity Growth and Convergence in Agriculture and Manufacturing’, mimeo, Development Research Group, the World Bank, Washington, D.C., June. Mellor, J. (1966). The Economics of Agricultural Development. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press. Mellor, J. (1976). The New Economics of Growth: A Strategy for India and the Developing World, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York. Mellor, J. (2001). Reducing poverty, Buffering Economic Shocks – Agriculture and the Non-Tradable Economy. Paper prepared for FAO consultation on the Roles of Agriculture in Development, 19-21 March 2001, Rome. Newman, M. D., R. Abbott, Liana C. Neff, J. Yeager, M. Menegay, D. Hughes, and J. Brown. (1989). ‘Agribusiness Development in Asia and the Near East’, Agricultural Marketing Improvement Strategies Project, Abt Associates Inc., Washington, D.C. Norway. (1999). ‘Appropriate Policy Measure Combinations to Safeguard Non-Trade Concerns of a Multifunctional Agriculture,’ Paper presented by Norway to the Informal Process of Analysis and Information Exchange of the WTO Committee on Agriculture, 28 September 1999. OECD. (1997). Environmental Benefits from Agriculture: Issues and Policies (The Helsinki Seminar), Paris: OECD. Oram, P.(1995). ‘The potential of technology to meet world food needs in 2020’, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC, April. Pinstrup-Anderson, Per. (1994). ‘World food trends and future food security’, Food Policy Statement, No. 18, International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, D.C., March. Ranis, G. (1984). ‘Typology in Development Theory: Retrospective and Prospects’, in M. Syrquin, L. Taylor and L. Westphal (eds), Economic Structure and Performance: Essays in Honor of Hollis B. Chenery, Academic Press: New York. Rosenstein-Rodan, P. N. (1943). ‘Problems of Industrialization of Eastern and SouthEastern Europe’, Economic Journal, 53, 202--11. Runge, C.F. (1999). Beyond the Green Box: A Conceptual Framework for Agricultural Trade and the Environment, Working Paper WP((-1, Center for International Food and Agricultural Policy, University of Minnesota. Saito, Katrine A. (1994). ‘Raising the Productivity of Women Farmers in Sub-Saharan Africa’, World Bank Discussion Paper 230, Africa Technical Department Series, Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Seldon, T.M. and D. Song. 1994. "Environmental Quality and Development: Is There a Kuznets Curve for Air Pollution Emissions?" Journal of Environmental Economics and Management 27(2): 147-62, September. Scitovsky, T. (1954). ’Two Concepts of External Economies’, Journal of Political Economy, 62, 143--51. Pryor, S. and T. Holt. (1999). ‘Agribusiness As An Engine Of Growth Social Studies’, 22, 2, 139--81. Singer, H. (1979). ‘Policy Implications of the Lima Target’, Industry and Development, 3, 17--23. Southworth, H.M., and B.F. Johnston, eds. (1967). Agricultural Development and Economic Growth. Ithaca NY: Cornell University Press,. Stringer, R. and Kym Anderson. (1999). ‘International Developments and Sustainable Agriculture in Australia’, Australian Agribusiness Review 7(2) June. Subbarao, K. and L. Raney, (1995). ‘Social Gains From Female Education: A CrossNational Study’, Economic Development and Cultural Change, 44 (1), October. Timmer, C.P., (1992). ‘Agriculture and Economic Development Revisited’, Agricultural Systems, 40:21-58. Timmer, C.P. (1995). Getting agriculture moving: do markets provide the right signals? Food Policy, vol 20, No. 5 p 455-472. Timmer, C.P., W. Falcon and S. Pearson. (1983). Food Policy Analysis, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. Vogel S. (1994). Structural changes in agriculture: production linkages and agricultural demand-led industrialization. Oxford Economic Papers Jan 1994 v46 n1 p136-157. World Bank. (1990). World Development Report, Washington, D.C.: World Bank. World Bank. 1992. “Development and the Environment.” World Development Report 1992, Washington D.C.: World Bank. World Bank. (1996). Reforming agriculture: The World Bank goes to market, Washington, D.C.: World Bank. Table 1 Share of Agriculture and agribusiness in GDP Country Philippines India Malaysia Indonesia Thailand Republic of Korea Chile Argentina Brazil Mexico United States Source: Pryor and Holt, 1999). Share of Share of GDP manufacturing ______________________________________ and services in Agriculture AgricultureAll agribusiness related agribusiness manufacturing and services ……………………..percent……………..…….. 22 38 60 70 31 45 76 60 17 26 43 73 19 29 48 63 12 37 49 79 7 22 29 82 7 25 32 79 6 20 26 73 8 18 26 79 7 19 26 75 2 4 8 91 Agriculture’s Economic Roles Food Security Environmental goods and services Direct Use Contributions Joint Products Externalities Traditional Food Surplus labour Exports Capital/savings transfers Consumer markets Indirect Use Contributions Public Goods Non traditional Produce agroindustrial goods Produce agroindustrial services Produce agroindustrial jobs Provide land for urban expansion Provide safe food Tourism Provide safe food Tourism Provide safe food More productive work force Welfare system substitute Productivity growth Rural viability Recreational amenities Cultural and heritage values Landscape values Equity contribution Enhanced learning capacity Provide community space Harbour unique ecosystems Increasingly less tangible values to society; and increasingly more difficult to measure contributions CIES DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES The CIES Discussion Paper series provides a means of circulating promptly papers of interest to the research and policy communities and written by staff and visitors associated with the Centre for International Economic Studies (CIES) at the Adelaide University. Its purpose is to stimulate discussion of issues of contemporary policy relevance among noneconomists as well as economists. To that end the papers are non-technical in nature and more widely accessible than papers published in specialist academic journals and books. (Prior to April 1999 this was called the CIES Policy Discussion Paper series. Since then the former CIES Seminar Paper series has been merged with this series.) Copies of CIES Policy Discussion Papers may be downloaded from our Web site at http://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/ or are available by contacting the Executive Assistant, CIES, School of Economics, Adelaide University, SA 5005 AUSTRALIA. Tel: (+61 8) 8303 5672, Fax: (+61 8) 8223 1460, Email: cies@adelaide.edu.au. Single copies are free on request; the cost to institutions is US$5.00 overseas or A$5.50 (incl. GST) in Australia each including postage and handling. For a full list of CIES publications, visit our Web site at http://www.adelaide.edu.au/cies/ or write, email or fax to the above address for our List of Publications by CIES Researchers, 1989 to 1999 plus updates. 0118 Stringer, Randy, "How important are the 'non-traditional' economic roles agriculture in development?" April 2001. 0117 Bird, Graham, and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Economic Globalization: How Far and How Much Further?" April 2001. (Forthcoming in World Economics, 2001.) 0116 Damania, Richard, "Environmental Controls with Corrupt Bureaucrats," April 2001. 0115 Whitley, John, "The Gains and Losses from Agricultural Concentration," April 2001. 0114 Damania, Richard, and E. Barbier, "Lobbying, Trade and Renewable Resource Harvesting," April 2001. 0113 Anderson, Kym, " Economy-wide dimensions of trade policy and reform," April 2001. (Forthcoming in a Handbook on Developing Countries and the Next Round of WTO Negotiations, World Bank, April 2001.) 0112 Tyers, Rod, "European Unemployment and the Asian Emergence: Insights from the Elemental Trade Model," March 2001. (Forthcoming in The World Economy, Vol. 24, 2001.) 0111 Harris, Richard G., "The New Economy and the Exchange Rate Regime," March 2001. 0110 Harris, Richard G., "Is there a Case for Exchange Rate Induced Productivity Changes?", March 2001. 0109 Harris, Richard G., "The New Economy, Globalization and Regional Trade Agreements", March 2001. 0108 Rajan, Ramkishen S., "Economic Globalization and Asia: Trade, Finance and Taxation", March 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1), April 2001.) 0107 Chang, Chang Li Lin, Ramkishen S. Rajan, "The Economics and Politics of Monetary Regionalism in Asia", March 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1), April 2001.) 0106 Pomfret, Richard, "Reintegration of Formerly Centrally Planned Economies into the Global Trading System", February 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1), April 2001). 0105 Manzano, George, "Is there any Value-added in the ASEAN Surveillance Process?" February 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1), April 2001). 0104 Anderson, Kym, "Globalization, WTO and ASEAN", February 2001. (Forthcoming in ASEAN Economic Bulletin, 18(1): 12-23, April 2001). 0103 Schamel, Günter and Kym Anderson, "Wine Quality and Regional Reputation: Hedonic Prices for Australia and New Zealand", January 2001. (Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Adelaide, 23-25 January 2001.) 0102 Wittwer, Glyn, Nick Berger and Kym Anderson, "Modelling the World Wine Market to 2005: Impacts of Structural and Policy Changes", January 2001. (Paper presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Adelaide, 23-25 January 2001.) 0101 Anderson, Kym, "Where in the World is the Wine Industry Going?" January 2001. (Opening Plenary Paper for the Annual Conference of the Australian Agricultural and Resource Economics Society, Adelaide, 23-25 January 2001.) 0050 Allsopp, Louise, "A Model to Explain the Duration of a Currency Crisis", December 2000.(Forthcoming in International Journal of Finance and Economics) 0049 Anderson, Kym, "Australia in the International Economy", December 2000. (Forthcoming as Ch. 11 in Creating an Environment for Australia's Growth, edited by P.J. Lloyd, J. Nieuwenhuysen and M. Mead, Cambridge and Sydney: Cambridge University Press, 2001.) 0048 Allsopp, Louise, " Common Knowledge and the Value of Defending a Fixed Exchange Rate", December 2000. 0047 Damania, Richard, Per G. Fredriksson and John A. List, "Trade Liberalization, Corruption and Environmental Policy Formation: Theory and Evidence", December 2000. 0046 Damania, Richard, "Trade and the Political Economy of Renewable Resource Management", November 2000. 0045 Rajan, Ramkishen S., Rahul Sen and Reza Siregar, "Misalignment of the Baht, Trade Imbalances and the Crisis in Thailand", November 2000. 0044 Rajan, Ramkishen S., and Graham Bird, "Financial Crises and the Composition of International Capital Flows: Does FDI Guarantee Stability?", November 2000. 0043 Graham Bird and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Recovery or Recession? Post-Devaluation Output Performance: The Thai Experience", November 2000. 0042 Rajan, Ramkishen S. and Rahul Sen, "Hong Kong, Singapore and the East Asian Crisis: How Important were Trade Spillovers?", November 2000. 0041 Li Lin, Chang and Ramkishen S. Rajan, "Regional Versus Multilateral Solutions to Transboundary Environmental Problems: Insights from the Southeast Asian Haze", October 2000. (Forthcoming in The World Economy, 2000.) 0040 Rajan, Ramkishen S., "Are Multinational Sales to Affiliates in High Tax Countries Overpriced? A Simple Illustration", October 2000. (Forthcoming in Economia Internazionale, 2000.) 0039 Ramkishen S. Rajan and Reza Siregar, "Private Capital Flows in East Asia: Boom, Bust and Beyond", September 2000. (Forthcoming in Financial Markets and Policies in East Asia, edited by G. de Brouwer, Routledge Press) 0038 Yao, Shunli, "US Permanent Normal Trade Relations with China: What is at Stake? A Global CGE Analysis", September 2000.