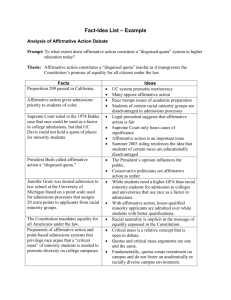

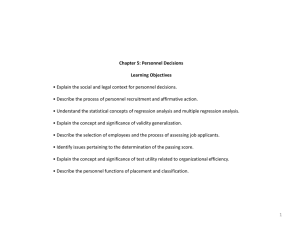

The Rise of Instrumental Affirmative Action

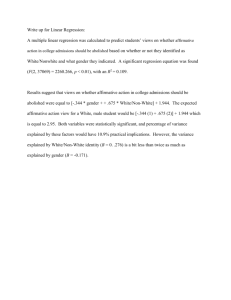

advertisement