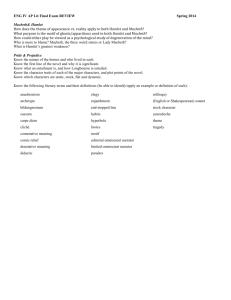

M.A. Thesis MADNESS IN SHAKESPEARE'S MAJOR TRAGEDIES

advertisement