Glossary.dramatic terms.tragedy.doc

Ms. Lenchak Page 1

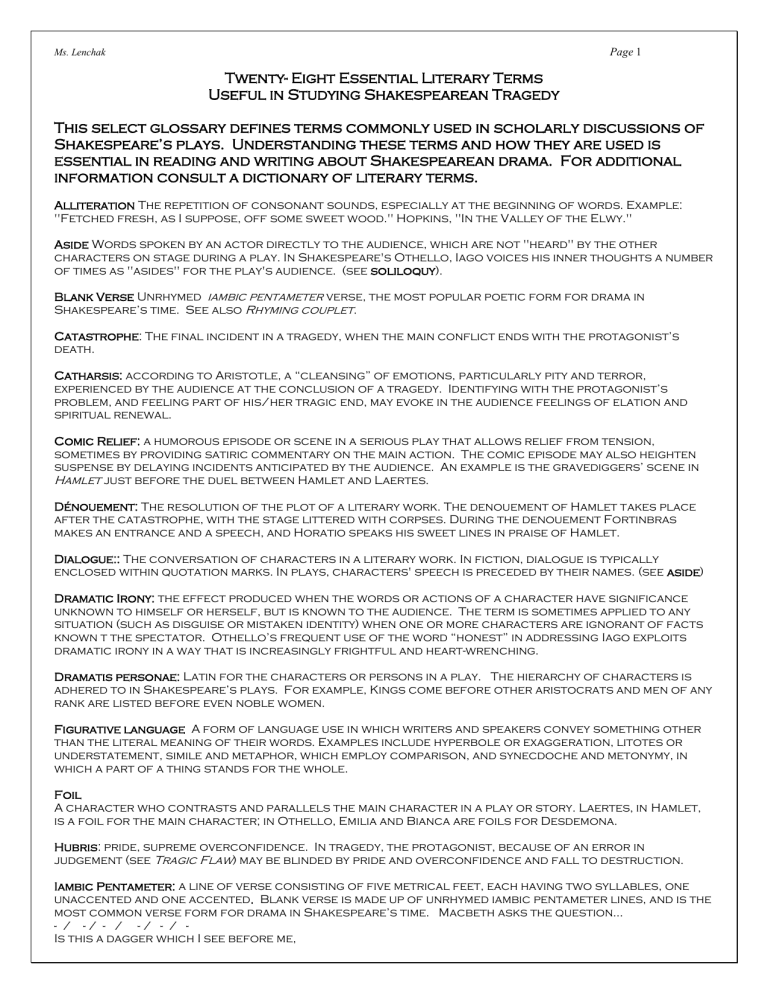

Twenty- Eight Essential Literary Terms

Useful in Studying Shakespearean Tragedy

This select glossary defines terms commonly used in scholarly discussions of

Shakespeare’s plays. Understanding these terms and how they are used is essential in reading and writing about Shakespearean drama. For additional information consult a dictionary of literary terms.

Alliteration The repetition of consonant sounds, especially at the beginning of words. Example:

"Fetched fresh, as I suppose, off some sweet wood." Hopkins, "In the Valley of the Elwy."

Aside Words spoken by an actor directly to the audience, which are not "heard" by the other characters on stage during a play. In Shakespeare's Othello, Iago voices his inner thoughts a number of times as "asides" for the play's audience. (see soliloquy).

Blank Verse Unrhymed iambic pentameter verse, the most popular poetic form for drama in

Shakespeare’s time. See also Rhyming couplet.

Catastrophe: The final incident in a tragedy, when the main conflict ends with the protagonist’s death.

Catharsis: according to Aristotle, a “cleansing” of emotions, particularly pity and terror, experienced by the audience at the conclusion of a tragedy. Identifying with the protagonist’s problem, and feeling part of his/her tragic end, may evoke in the audience feelings of elation and spiritual renewal.

Comic Relief: a humorous episode or scene in a serious play that allows relief from tension, sometimes by providing satiric commentary on the main action. The comic episode may also heighten suspense by delaying incidents anticipated by the audience. An example is the gravediggers’ scene in

Hamlet just before the duel between Hamlet and Laertes.

Dénouement: The resolution of the plot of a literary work. The denouement of Hamlet takes place after the catastrophe, with the stage littered with corpses. During the denouement Fortinbras makes an entrance and a speech, and Horatio speaks his sweet lines in praise of Hamlet.

Dialogue:: The conversation of characters in a literary work. In fiction, dialogue is typically enclosed within quotation marks. In plays, characters' speech is preceded by their names. (see aside)

Dramatic Irony: the effect produced when the words or actions of a character have significance unknown to himself or herself, but is known to the audience. The term is sometimes applied to any situation (such as disguise or mistaken identity) when one or more characters are ignorant of facts known t the spectator. Othello’s frequent use of the word “honest” in addressing Iago exploits dramatic irony in a way that is increasingly frightful and heart-wrenching.

Dramatis personae: Latin for the characters or persons in a play. The hierarchy of characters is adhered to in Shakespeare’s plays. For example, Kings come before other aristocrats and men of any rank are listed before even noble women.

Figurative language A form of language use in which writers and speakers convey something other than the literal meaning of their words. Examples include hyperbole or exaggeration, litotes or understatement, simile and metaphor, which employ comparison, and synecdoche and metonymy, in which a part of a thing stands for the whole.

Foil

A character who contrasts and parallels the main character in a play or story. Laertes, in Hamlet, is a foil for the main character; in Othello, Emilia and Bianca are foils for Desdemona.

Hubris: pride, supreme overconfidence. In tragedy, the protagonist, because of an error in judgement (see Tragic Flaw) may be blinded by pride and overconfidence and fall to destruction.

Iambic Pentameter: a line of verse consisting of five metrical feet, each having two syllables, one unaccented and one accented. Blank verse is made up of unrhymed iambic pentameter lines, and is the most common verse form for drama in Shakespeare’s time. Macbeth asks the question…

- / - / - / - / - / -

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

Ms. Lenchak Page 2

Imagery Mental impressions created by skilful use of diction that appeal to any of the five senses.

Figurative language which conveys word pictures and evokes imaginative and emotional response.

Shakespeare’s tragedies are marked by recurring images related word pictures that support or extend thematic ideas. For example, Hamlet’s metaphorical reference to Denmark as “an unweeded garden” is echoed often in later dialogue. See Metaphor, Motif, Symbol

Machiavellian: a dissembling villain for whom the end – his own success – justifies the means. He does anything necessary to serve his own

Metaphor

A comparison between essentially unlike things without an explicitly comparative word such as like or as. For example, Iago tells us he will use a little ”web” to “ensnare as great a fly as Cassio,” implying that his clever schemes will deceive and destroy his rival, Lieutenant Cassio. Shakespeare employs a wide range of metaphors in his sonnets and his plays, often in such density and profusion that readers are kept busy analyzing and interpreting and unravelling them. See Simile and

Personification

Mood: the feeling evoked in the audience by a dramatist’s creation of atmosphere through dialogue and action. For example, the opening scene of Hamlet, late at night on the battlements of Elsinore, creates an atmosphere of mystery and suspense. Anxious sentries talk uneasily about a ghostly visitor. The mood evoked in the audience is one of nervous excitement and anticipation.

Motif: a recurring idea that resonates through a literary work, often punctuating an important theme. The guilt-ridden, troubled sleep of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth is an effective motif in the last two acts of the play. See also Imagery, Symbol

Nemesis: retributive justice, appropriate punishment for wickedness. In Greek mythology, Nemesis was a goddess of vengeance. The term sometimes extends to include appropriate reward for virtue.

Pathetic Fallacy: the representation of nature as being in sympathy with, or affected by the emotions and actions of human beings. The onset of King Lear’s stormy madness is reflected in the real storm thundering over his head.

Paradox: an apparent contradiction which may nevertheless contain a truth. When Iago says, “I am not what I am,” the paradox suggests his hypocritical, dissembling nature, and supports the

“appearance vs reality” motif that dominates the play, Othello.

Pathos

A quality of a play's action that stimulates the audience to feel pity for a character. Lear’s return to reason, awakening in the care of his wronged daughter Cordelia, is a scene of great pathos.

Rhyming Couplet: a pair of consecutive rhyming lines, often used by Shakespeare to mark the end of an incident or scene, or to emphasize a significant idea. (often in a proverbial expression)

Soliloquy

A speech expressing a character’s thoughts, usually when he or she is alone on stage. Hamlet's "To be or not to be" speech is an example. A soliloquy may reveal character, comment on the current situation, or explain the character’s plans, thereby preparing the audience for subsequent events.

See Aside.

Symbol

An object or action in a literary work that means more than itself, that stands for something beyond itself. Hamlet’s philosophical comments in the graveyard are extended and emphasized when he takes up the skull of Yorick. His memories of the dead jester confirm his melancholy views about death. The skull or death’s head is a traditional symbol for the transitory nature of human life and achievement, a recurring motif of the play.

Tragic flaw

A weakness or limitation in the protagonist’s otherwise noble nature, resulting in the fall of the tragic hero. Othello's jealousy and too trusting nature is one example.

Word Play: witty and humorous dialogue that depends on sound-alike words or multiple meanings.

Puns, quibbles and riddles are examples. More serious traditional figures of speech, such as oxymoron and metonymy are sometimes including under this general heading.