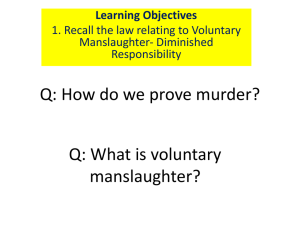

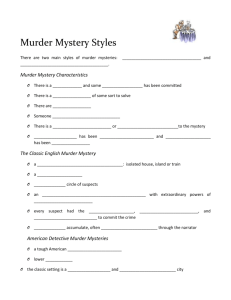

Murder, manslaughter and infanticide

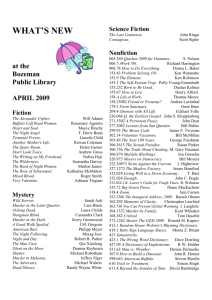

advertisement