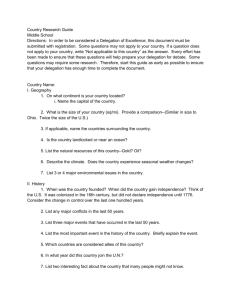

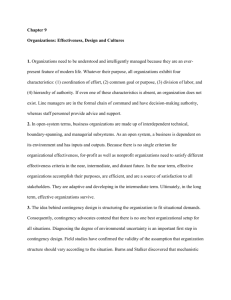

1 Uncertainty, Task Environment, and Organization Design

advertisement