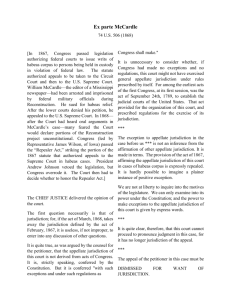

Constitutional Limits on Extraterritorial Jurisdiction

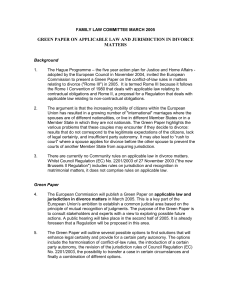

advertisement