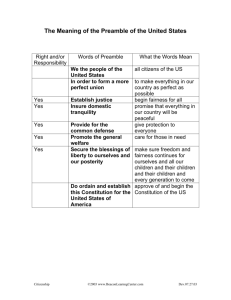

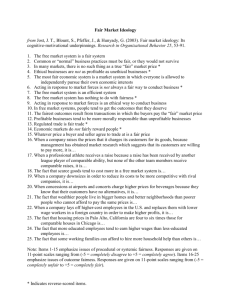

The changing contours of fairness

advertisement