Original Jurisdiction - Supreme Court of Pakistan

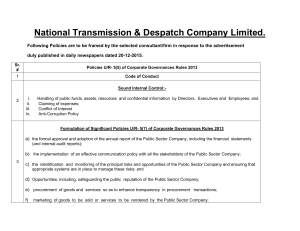

advertisement