Notebook

Care of the Patient with Hematological

Disorders

Lesson 1: Hematologic and Immunologic System Anatomy

and Physiology

Lesson 2: Assessment, Diagnostic Tests and Monitoring

Systems

Lesson 3: Pathologic Conditions Patient

Inside:

•

Module Outline

•

Lesson Objectives

•

Lesson Summary

•

Lesson Resource Files

•

Lesson Practice Pearls

2

Module Outline

Module 9 - Care of the Patient with Hematological Disorders

Lesson 1 - Hematologic and Immunologic System Anatomy and Physiology

Topic 1: Structures, Components and Functions

Topic 2: Coagulation Mechanism and Fibrinolysis

Topic 3: Immunologic Basics

Lesson 2 - Assessment, Diagnostic Tests and Monitoring Systems

Topic 1: Hematology Studies

Topic 2: Coagulation Studies

Topic 3: Immunology Studies

Lesson 3 - Pathologic Conditions

Topic 1: Anemia

Topic 2: Thrombocytopenia

Topic 3: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

Topic 4: Immunocompromise

Topic 5: Other Coagulopathies

Lesson 1

Hematologic and Immunologic

System Anatomy and Physiology

Included in this Lesson:

• Structures, Components and Functions

• Coagulation Mechanism and Fibrinolysis

• Immunologic Basics

4

Lesson: Hematologic System Anatomy & Physiology

Objectives

Topic:

Introduction

Upon completion of this lesson you will be able to:

•

Identify and discuss function of components of hematologic systems

-

Describe the structures and functions of the components of the

hematologic system

-

Discuss the mechanism of coagulation and fibrinolysis

Page of 3

5

Lesson Take-away - Hematologic System Anatomy and Physiology

Topic One: Structures, Components and Functions

Importance of Understanding the Hematologic System

In this lesson we looked at the anatomy and physiology of the hematologic system and learned why an understanding of the

hematologic system is so essential to the acute care clinician. We learned that something as routine as bedrest can lead to

clot formation (deep vein thrombosis) and a pulmonary emboli. We also learned that disseminated intravascular coagulation

(DIC) could result from any tissue damage and that anemia and thrombocytopenia can be common in acutely ill patients.

Assessment of the hematologic system is an essential part of assessing a patient in acute care and it includes:

• Taking a history of any predisposing factors

• Assessing and exploring in depth any personal or genetic history of bleeding, chronic anemia, or systemic diseases such

as renal failure, liver disease, or cancer

• Asking whether the patient is taking any medication affecting the hematologic system such as anticoagulant drugs such as

warfarin, unfractionated or low-molecular weight heparin, antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin or clopidogrel, and steroids or

non-steroidal medications such as ibuprofen

• Noticing any physical signs which may indicate an underlying hematologic problem such as pale or jaundiced skin color, a

history of unexplained bruising or clotting or ecchymosis, and petechiae.

• Noticing other symptoms like hematochezia or melena, hematuria, hemoptysis, and menorrhagia.

Anatomic Structures

The anatomic structures of the hematologic system are as follows:

• Bone marrow – The spongy material in the center of the bones, particularly long bones and also in the skull, vertebrae,

ribs, and pelvis. It is in the bone marrow that the cells of the hematologic system and the immunologic system originate,

mature, and are released into the bloodstream.

• Liver – Removes nonfunctioning erythrocytes from the blood stream.

• Spleen – Removes damaged erythrocytes from the blood.

• The following cellular components:

• Red blood cells or erythrocytes

• Platelets or thrombocytes

• Coagulation factors

• Stem cells – All cells produced by the bone marrow (and therefore all hematologic and immunologic system cells)

originate from the stem cell. Stem cells produce daughter cells which then differentiate into one of the two following

types of cells:

• lymphoid stem cells (these produce ß cells which function in the immune system)

• myeloid stem cells (these produce erythrocytes and thrombocytes)

Erythrocyte production is stimulated during hypoxemia by the kidney which, in response to hypoxemia occurring, produces

the hormone erythropoietin in order to get the stem cells in the bone marrow to make erythrocytes. This erythrocyte

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

Page of 3

6

production is important since erythrocytes have hemoglobin, the substance that transports the needed oxygen to tissues for

aerobic metabolism (ATP production) and removal of CO2 (the byproduct of oxygen metabolism.) This transport by

erythrocytes of oxygen via the blood to tissues throughout the body is called “oxygenation.”

Thrombocyte or platelet production and the coagulation mechanism is stimulated/activated during a tissue injury or blood

vessel injury. When such an injury occurs, platelets rush to the site of injury and form a platelet plug. Cytokines are released,

causing additional platelets to be activated, the coagulation mechanism to continue, and an immune response to be

stimulated.

Topic Two: Coagulation Mechanism and Fibrinolysis

Two Main Functions

The hematologic system’s two main functions are oxygenation (discussed above) and homeostasis. Homeostasis is the

process of clotting or coagulation in order to prevent hemorrhage and the corresponding mechanism of fibrinolysis, the

dissolving of the blood clot to some degree so that it doesn’t become too large.

Coagulation and Fibrinolysis

Homeostasis is the body’s system of self-regulating and it is accomplished through the coagulation mechanism. The

coagulation mechanism is a combination of two seemingly opposite activities: clotting and “fibrinolysis” (clot-dissolving; the

breaking up of and limiting the size of clots.) This second activity is the body’s way of preventing hemorrhaging while, at the

same time, ensuring that it doesn’t clot too much; only enough to stop the bleeding. Once the bleeding has been stopped,

clot-dissolving begins.

Clot-dissolving occurs by a blood protein dissolving the clot, breaking down the fibrin into fragments. We can get information

about the clot-dissolving activity by measuring the levels of “fibrin split products” or “fibrin degradation products” (the

fragments created when fibrin is broken down.)

We examined this coagulation mechanism in more detail and learned that the coagulation mechanism is a cascade of

events involving 12 factors and several cofactors (plasma proteins.) This cascade of events always ends in the production of

thrombin (Factor IIa.)

While the cascade of events always ends in thrombin being produced, it begins or is initiated in one of two ways: through an

intrinsic pathway (in response to vessel wall damage,) or through an extrinsic pathway (in response to tissue damage.) The

end result, however, is always the same: thrombin (Factor IIa) is produced. Thrombin splits circulating fibrinogen (Factor I) to

form fibrin and the blood clot.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

Page of 3

7

Related Drugs

In acute and critical care there exist drugs which inhibit or enhance the coagulation mechanism and fibrinolysis. Some of

these drugs are:

• Anticoagulants – prevent coagulation (clotting.) Can be used in viro as a medication for thrombotic disorders.

• Antiplatelet drugs – decrease platelet aggregation and inhibit thrombus formation. Are effective in arterial circulation—an

area where anticoagulants have little effect.

• Thrombolytic agents – can dissolve a blood clot (thrombus) and reopen an artery or vein

• Antifibrinolytic agents – prevent fibrinolysis or lysis of a blood clot

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

8

Lesson: Hematologic System Anatomy & Physiology

Cellular Components

Topic:

Structures, Components and Functions

Cellular Components

Stem cells

Myeloid

stem cell

Erythrocytes

Lymphoid

stem cell

Platelets

B-cells

T-cells

9

Coagulation Mechanism

Lesson: Hematologic System Anatomy & Physiology

Topic:

Structures, Components and Functions

Coagulation Mechanism

Extrinsic Pathway

Intrinsic Pathway

Tissue damage

Vessel wall

damage

VII → VIIa

Tissue factor

XI → XIa

VII → VIIa

IX → IXa

X → 7 Xa

Thrombin

Fibrin

Clot

10

Hematology Drugs

Lesson: Hematologic System Anatomy & Physiology

Topic:

CLASS OF DRUG

Structures, Components and Functions

NAME OF DRUG

THERAPEUTIC USE

Anticoagulants

Indirect Thrombin

Inhibitors

Unfractionated Heparin

Treatment or prevention of

venous thrombosis.

Adjunct to thrombolytic therapy

with ACS

Low Molecular Weight Heparins

Ardeparin (Normiflo)

Enoxaparin (Lovenox)

Dalteparin (Fragmin)

Prevention of venous

thromboemboli

Fondaparinux (Arixta)

Prevention of venous

thromboemboli with the risk of

HIT because the agent is

synthetic not made from animal

proteins which heparin and

LMWH are

Hirudin Derivatives

Lepirudin (Refludan)

Bivalirubin (Angiomax)

Heparin substitute for patients

at risk or experiencing HIT

Argatroban (Acova, Novastan)

Heparin substitute for patients

at risk or experiencing HIT

Recombinant Human

Activated Protein C

(sometimes categorized

as a thrombolytic agent)

Drotrecogin alpha activated (Xigris)

Severe sepsis

Vitamin K Antagonist

Warfarin (Coumadin)

Prevention of venous

thromboemboli development

Direct Thrombin Inhibitors

11

Antiplatelet Drugs

Cyclooxygenase Inhibitor

Aspirin

At antiplatelet dose (75-325mg)

Primary and secondary

prevention and treatment for

ACS. Secondary prevention in

stroke.

Adenosine Diphosphate

Receptor Antagonists

Ticlopidine (Ticlid)

Clopidogrel (Plavix)

Reduction of atherosclerotic

events in patients with recent

stroke or MI.

Vascular disease

Dipyridamole (Persantine)

Thromboembolism prevention

follow cardiac valve surgery

Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa

Receptor Antagonist

Abciximab (ReoPro)

Eptifibatide (Integrelin)

Tirofiban (Aggrastat)

Acute coronary syndrome with

or without percutaneous

coronary intervention (PCI)

Thrombolytic Agents

Streptokinase (Kabikiane, Streptase)

Alteplase (tPA)

Reteplase (rtPA)

Teneteplase (TNKase)

ACS, DVT, PE

Adjunct to PCI

Thrombotic Stroke

Antifibrinolytic Agents

Aminocaproic Acid

(EACA, Amicar, Epsilson)

Aprotinin (Trasylol)

Coagulopathies with

hemorrhage

Lesson 2

Assessment, Diagnostic Tests and

Monitoring Systems

Included in this Lesson:

• Hematology Studies

• Coagulation Studies

• Immunology Studies

13

Lesson: Hematologic Diagnostic Tests

Objectives

Topic:

Hematology Studies

Upon completion of this lesson you will be able to:

•

Analyze basic hematologic and immunologic laboratory test results

-

Identify normal and abnormal complete blood count results

-

Identify normal and abnormal white blood cell differential

-

Identify normal and abnormal erythrocyte sedimentation rate

-

Identify normal and abnormal prothrombin time and international

normalization ratio

-

Identify normal and abnormal partial thromboplastin time

-

Identify normal and abnormal fibrinogen

-

Identify normal and abnormal fibrin split levels/D-dimer

-

Identify normal and abnormal results of basic immunology studies

Page of 4

14

Lesson Take-away - Hematologic Diagnostic Tests

Topic One: Hematology Studies

The Importance of Understanding Hematologic Diagnostic Tests

In this lesson we discussed the diagnostic tests commonly used to identify hematologic disorders and alterations in

coagulation. These common diagnostic tests are important for helping you to evaluate the hematologic status of a patient,

diagnose disorders, and anticipate the type of treatment a patient requires.

The hematologic system is evaluated through the use of several laboratory tests. Laboratory tests are the main source of

assessment data for evaluating hematologic health.

The Complete Blood Count (CBC)

The CBC is a lab test that provides information about many different things which are of significance to the hematologic

system including:

• Platelet count (Remember that platelets are also called thrombocytes.)

• Hematocrit and hemoglobin – These rise and fall linearly with the RBC count, however they are also affected by

intravascular volume status.

• RBC count (Red Blood Cell count.) Remember that mature red blood cells are also called erythrocytes.

• A high RBC could indicate erythrocytosis.

• A low RBC could indicate anemia. A common reason for a low RBC count is bleeding. However, RBC

could also be low due to a lack of production of erythrocytes from bone marrow suppression or early

destruction of red cells from hemolysis or sickle cell disease.

Through the use of mathematical formulas, the following red blood cell indices-which are usually calculated automatically in

a CBC-help the clinician to narrow down the cause of an anemia more clearly, if other than bleeding. The red blood cell

indices are MCV, MCHC, and RDW.

Mean Corpuscular Volume (MCV)

MCV measures the average volume of a red blood cell (by dividing the hematocrit by the RBC) and indicates whether it

(MCV) is normal, decreased, or increased. Also categorizes the red blood cells by size, indicating that they are either

“normocytic” (normal sized,) “microcytic” (smaller sized,) or “macrocytic” (larger sized.) With all of this information, we can

characterize the type anemia present:

• Normocytic anemias have normal-sized cells and a normal MCV

• Microcytic anemias have small red blood cells and a decreased MCV

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

Page of 4

15

• Macrocytic anemias have large red blood cells and an increased MCV

Under a microscope, stained red blood cells having a high or increased MCV also appear macrocytic or larger sized than

those having normal or decreased MCV.

Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC)

MCHC measures the average concentration of hemoglobin in a red blood cell (by dividing the hemoglobin by the

hematocrit.) and indicates whether the cells are “normochromic” (having a normal concentration of hemoglobin) or

“hypochromic” (having a lower than normal concentration of hemoglobin.) Because there is a physical limit to the amount of

hemoglobin that can fit in a cell, there is no “hyperchromic” category. Remember that it is the hemoglobin in red blood cells

(or erythrocytes) that transports the needed oxygen to tissues in the body. Therefore hemoglobin is very important.

The iron in hemoglobin is what gives blood its characteristic red color. When examined under a microscope, normochromic

cells (red blood cells having a normal amount of hemoglobin and thereby a normal MCHC) stain pinkish red with a paler

area in the center. By contrast, hypochromic cells (red blood cells having too little hemoglobin and thereby a lower MCHC)

are lighter in color with a larger pale area in the center. With the information provided by the MCHC index, we can

characterize the type of anemia present as hypochromic or normochromic.

Cell Distribution Width (RDW)

RDW measures the variation in size in the red blood cells. Usually red blood cells are a standard size. Certain disorders,

however, cause significant variation in cell size.

Other Tests

Besides the CBC, we also looked at these tests for evaluating hematologic health:

• Reticulocyte (immature erythrocyte) count – Measures the amount of reticulytes in order to determine whether or not the

patient is making the correct amount of new red blood cells. (Recall that all hematologic cells originate from stem cells. The

stem cells produce daughter cells which then differentiate into one of two types of cells, one type being myeloid stem cells

from which erythrocytes and thrombocytes are produced.) Once a stem cell becomes an erythrocyte it is a reticulocyte first

for about two weeks. As long as the patient is well nourished, has a functioning liver, and produces a healthy red cell, the

reticulocyte eventually matures into a fully functioning erythrocyte.

• ESR (Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate, or sed rate) – Measures the heaviness of the red cell.

• An increase in ESR or sed rate reflects inflammation in the body. Although an increased sed rate or ESR does not

tell the cause of the inflammation (sepsis or rheumatoid arthritis,) it at least alerts the clinician that there is

inflammation. The correlation between inflammation and increased sed rate is as follows: When inflammation is

present, a high proportion of fibrinogen is in the blood and this causes red blood cells to stick to each other, forming

stacks called 'rouleaux' which settle faster.

• ESR is decreased in sickle cell anemia, polycythemia, and heart failure.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

Page of 4

16

• Bilirubin levels. Bilirubin is the name for broken up red blood cells. The average life span of a erythrocyte or mature red

blood cell is 120 days at which point it gets broken up and becomes bilirubin. Bilirubin is fat soluble and in order to be

excreted, must be converted to a water soluble form. Ths conversion occurs in the liver.

• An elevation of unconjugated (indirect) bilirubin reflects either an increase in hemolysis or liver dysfunction.

• An elevation of conjugated (direct) bilirubin indicates that the liver has converted the bilirubin but that it was

blocked from being excreted for some reason. One such reason might be the presence of gallstones.

Topic Two: Coagulation Studies

Assessing Patient’s Coagulation State

Recall from Lesson 1 that the hematologic system’s two main functions are oxygenation (red blood cells) and homeostasis.

Homeostasis is the combination of both clotting/coagulation (in order to stop hemorrhage) and fibrinolysis (clot dissolving;

occurs once the bleeding has been stopped and in order to keep clotting from continuing unchecked.)

Coagulation is always initiated either through an intrinsic pathway (vessel wall damage) or through an extrinsic pathway

(tissue damage) and that both events result in thrombin (Factor IIa) being produced. Thrombin is one of many plasma

proteins (12 clotting factors and several co-factors) which play a role in coagulation or clotting. Thrombin forms fibrin and the

blood clot by splitting circulating fibrinogen (Factor I.) In Lesson 1 we also looked at some of the drugs used for inhibiting

and enhancing both coagulation and fibrinolysis.

Recall that clot-dissolving occurs by fibrin being broken down into fragments called “fibrin split products” or “fibrin

degradation products.” Measuring the levels of these fibrin split products or fibrin degradation products can provide us

information about clot-dissolving within a particular patient.

There are several blood studies which can be used to assess whether coagulation and fibrinolysis are occurring normally in

a patient. They are as follows:

• Tests that determine whether a patient has the plasma proteins (clotting factors) needed to form a clot.

• PT (Prothrombin Time) and the INR (International Normalized Ratio) - Help assess the extrinsic pathway of the

coagulation mechanism

• PTT (Partial Thromboplastin Time) - Helps identify the intrinsic pathway of the coagulation mechanism

The PT, INR, and PTT are also used to assess the effectiveness of anticoagulation therapy. For example, the PT is used to

evaluate the effectiveness of warfarin and the PTT is used to evaluate heparin therapy.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

Page of 4

17

• A Bleed Time test - Can help determine vascular integrity and platelet function or the patient’s ability to clot when

necessary.

• A review of the platelet (thrombocyte) count (the count done as part of the CBC) is helpful because it can help determine

the patient’s ability to clot. Recall that platelets and the plasma proteins (clotting factors and co-factors) are what initiate

clotting and form the foundation for the blood clot.

• A look at fibrinogen level. The fibrinogen level reflects the circulating amount of factor I, which is necessary to form a

clot. Fibrogen levels will be low when a patient has made clots and may be elevated with sepsis.

• A look at the level of fibrin split products (also called fibrin degradation products). This looks at the amount of circulating

broken up fibrin or clots is important. For example, elevations in D-Dimer - a type of fibrin split product produced when cross

linked fibrin is broken up - are common when the clots formed are from deep vein thrombosis, disseminated intravascular

coagulation, many cancer states, and sickle cell crisis.

• Thrombin Time (TT) – This test can be helpful in evaluating the effectiveness of anticoagulation thrombolytic agents like

tissue plasminogen activator (tPa) once they have been administered.

• Using the Activating Clotting Time (ACT) test in conjunction with a PTT to evaluate anticoagulation with heparin therapy.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

18

Hematologic Study Table

Lesson: Hematologic Diagnostic Tests

Topic:

Red Blood Cell Laboratory Tests

Hematology Studies

19

Lesson: Hematologic Diagnostic Tests

Coagulation Studies

Topic:

TEST

Platelet Count

Prothrombin Time (PT)

Coagulation Studies

NORMAL RANGE

150,000400,000/mm3

11-15 seconds

International Normalized

Ratio (INR)

0.7 – 1.8

Activated Partial

Thromboplastin Time

(aPTT)

PTT 60 – 70

seconds

Anti-Factor Xa

0 units/mL

DVT tx:

LMWH 0.4 1.1 U/ml

DVT Prophylaxis:

< 0.45 U/ml

Depends on system

Ivy 1-8, Duke 1-3min

70 – 120 seconds

Bleeding Time

Activated Clotting Time

(ACT)

PARAMETER MEASURED

# of Circulating Platelets, Measures

Amount not Functional Ability

Extrinsic & Common Coagulation

Pathways

Evaluation of Warfarin Therapy

Standardized method of reporting the PT

Evaluation of Warfarin Therapy

Intrinsic & Common Coagulation

Pathways

Evaluation of Heparin Therapy

Low Molecular Weight Heparin

Monitoring

Normal Platelet and Tissue Function

with Bleeding

Fibrinogen

Thrombin Time (TT)

200 - 400mg/dL

14 -16 sec

Fibrin Degradation (Split)

Products

D-Dimer

2-10mcg/ml

Intrinsic & Common Coagulation

Pathways

Evaluation of Heparin Therapy

Circulating Fibrinogen

Common Coagulation Pathway and

Quality of the Functional Fibrinogen

Evaluation of tPA therapy

Degree of Fibrinolysis

< 2.5mcg/ml

Specific Fibrin Breakdown Product

Lesson 3

Pathologic Conditions

Included in this Lesson:

• Anemia

• Thrombocytopenia

• Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

• Immunocompromise

• Other Coagulopathies

21

Objectives

Module: Care of the Patient with Hematologic Disorders

Lesson: Pathologic Conditions

Upon completion of this lesson you will be able to:

•

Describe the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, management

of critically ill patients with:

- Anemia

- Thrombocytopenia

- Disseminated intravascular coagulation

•

Describe the etiology, pathophysiology, clinical presentation, and

management of critically ill patients with other coagulapathies

22

Page of 8

Lesson Take-away - Pathologic Conditions

Topic One: Anemia

Common Hematologic Disorders

In Lesson 3 we covered hematologic disorders commonly encountered in the critically ill patient population. Understanding

anemia, thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC) depends on one understanding the

coagulation pathways as well as the diagnostic tests used to identify the various disorders.

Anemia Basics

Anemia by definition is a low red blood cell count. Anemia is seen in many critically ill patients. Employing interventions that

minimize blood loss will help prevent anemia.

The human body is fueled by oxygen. The oxygen is delivered to all the cells and organs by hemoglobin. When there is a

lack of or inadequate delivery of oxygen, the body will not function normally. The primary problem with anemia is a

decreased number of red blood cells. Since red blood cells have hemoglobin, decreased red blood cells means decreased

ability for the body to have adequate oxygen delivery.

The etiologies for anemia can be classified into these three categories:

• Blood Loss - This is certainly the easiest to

• Early Elimination/Destruction of red blood cells

understand and also the most frequent cause of anemia

Destruction of red blood cells, called “hemolysis,” can be

in the hospitalized patient. The loss could be from

enhanced by things like the cardiopulmonary bypass

trauma, surgery, gastrointestinal bleeding or conditions

machine, intra-aortic balloon pumping, and mechanical

that increase the bleeding such as disseminated

heart valves. Activation of the immune response can cause

intravascular coagulation, anticoagulant administration

a hemolytic anemia as can sickle cell anemia/disease,

and excessive blood draws.

G6PD deficiency, and thrombotic thrombocytopenia

• Underproduction of red blood cells This could occur

purpura.

from malnutrition, chronic illness, malignancies and

cancer therapies or from organ dysfunction specifically

liver or renal.

By definition, anemia is a low red blood cell count. It

becomes clinically significant when the cells/organs are not

receiving enough oxygen and the body begins initiating

compensatory mechanisms, all of which have the single

goal of increasing oxygen delivery.

Symptomatic anemia will present on assessment with

tachycardia, weak pulses, orthostatic hypotension, ECG

changes, an increased respiratory rate and work of

breathing, pale skin and mucous membranes, decreased

urinary output, and a decreased level of consciousness.

The degree of symptoms related directly to the degree of

anemia and also the timeframe within which the anemia

has developed. At the point that oxygen delivery becomes

inadequate for the body’s demands, the patient crosses the

line from anemia into hypovolemic shock. The acutely or

chronically ill adult may not have the physiological reserve

to mount a strong compensatory response to anemia.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

23

Page of 8

The primary goal in anemia management in acute care is

adequate oxygen delivery. So the treatment options are

guided by the severity of the patient’s symptoms more than

by the absolute number listed on the CBC for RBC count or

hemoglobin.

To accomplish adequate oxygen delivery, packed red

blood cells are administered. Additional treatments include

supplemental oxygen, minimizing activity, and optimizing

cardiac output and pulmonary function. The administration

of recombinant human erythropoietin or supplemental

vitamins and minerals might also help the development and

Sickle Cell Disease (SSD)

Sickle Cell Disease (SSD,) frequently referred to as sickle

cell anemia, manifests as a life-long hemolytic anemia. To

have SSD a person must inherit the “hemoglobin S” (HgbS)

trait from both of their parents. The abnormal Hgb causes

an altered shape (sickle shape) which results in a

decreased ability to carry oxygen and a decreased lifespan

by the red blood cells, thereby accounting for the anemia.

A person with SSD may also experience crises from the

microvascular hypoxia and clotting that can occur. Crises

may be stimulated by an infection, cold temperature,

acidosis, dehydration, or changes in atmospheric oxygen

(altitude.) The patient will present with severe pain, fever,

fatigue, tachycardia, tachypnea, and hematuria.

release of healthy red blood cells from the bone marrow.

The cause for the anemia must be identified and treated.

Blood conservation policies should be considered on all

acute and critically ill patients and heightened for those

with anemia. Strategies that may help decrease the

incidence of anemia are:

• Limiting blood draws

• Using autotransfusion whenever possible

• Administering gastrointestinal bleeding

prophylaxis medications

Laboratory findings include a low RBC, HCT, Hgb, and

elevated reticulocyte (immature red blood cells) counts

typically with a microcytic anemia. Patients with coexisting

vascular disease are at high risk for stroke or ACS during

crises.

There is no cure for SSD so treatment is currently directed

at anemia management and crises prevention. Should

crises occur, our goal is to manage symptoms. The primary

methods are:

• Hydration

• Oxygen administration

• Pain medication administration

Plasma exchange and hyperbaric chamber therapy have

also been used.

Sickle Cell Crisis Patterns

There are now four recognized patterns of acute sickle cell crisis:

• Bone Crisis - An acute or sudden pain in a bone can occur, usually in an arm or leg. The area may be tender. Common

bones involved include the large bones in the arm or leg: the humerus, tibia, and femur. The same bone may be affected

repeatedly in future episodes of bone crisis.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

24

Page of 8

• Acute Chest Syndrome - Sudden acute chest pain with coughing up of blood can occur. Low-grade fevers can be

present. The person is usually short of breath. If a cough is present, it often is nonproductive. Acute chest syndrome is

common in a young person with sickle cell disease. Chronic (long-term) sickle cell lung disease develops with time because

the acute and subacute lung crisis leads to scarred lungs and other problems.

• Abdominal Crisis - The pain associated with the abdominal crisis of sickle cell disease is constant and sudden. It

becomes unrelenting. The pain may or may not be localized to any one area of the abdomen. Nausea, vomiting, and

diarrhea may or may not occur.

• Joint Crisis -Acute and painful joint crisis may develop without a significant traumatic history. Its focus is either in a single

joint or in multiple joints. Often the connecting bony parts of the joint are painful. Range of motion is often restricted because

of the pain.

Hemophilia

Hemophilia is an X chromosome-linked inherited bleeding

disorder. Although females can carry the gene, only males

can have the disease. Hemophiliacs lack the normal

amounts of either clotting factor VIII or clotting factor IX.

Because of their inadequate clotting ability, they are at high

risk their entire life for mild, moderate, and severe bleeding.

When not bleeding this patient will have a normal PT, TT,

and Bleeding Time but a prolonged aPTT, and of course

low factor VIII or IX levels. During bleeding episodes, the

above coagulation studies will be elevated.

The treatment for hemophilia is to prevent bleeding risk.

When bleeding does occur, the goal is to limit blood loss

and, if necessary, transfuse the patient with packed red

blood cells, FFP, platelets, and cryoprecipitate (which has

factor VIII.) Patients might also be given sterile factor

concentrates of factor VIII to help enhance clotting and limit

bleeding.

Recombinant human factor VIIa (“rhVIIa”) has been

approved for the use of bleeding associated with

hemophilia. Medications to enhance clotting like DDAVP or

antifibrinolytic agents might also be utilized to control

hemorrhage.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

25

Page of 8

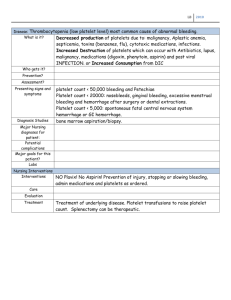

Topic Two: Thrombocytopenia

Thrombocytopenia Basics

Like anemia, Thrombocytopenia is also fairly common in

critically ill. It is one of the most common coagulation

disorders identified in the acutely ill adult population. Some

common interventions such as the administration of

heparin may lead to the development of thrombocytopenia.

difficult. In fact, the term “idiopathic thrombocytopenic

purpura” or ITP—a term for thrombocytopenia where the

clinical team is unable to determine the origin of the low

platelet count—is the most common documented etiology

for thrombocytopenia.

Thrombocytopenia is defined as an abnormally low number

of platelets resulting in inadequate hemostasis. Since

platelets play a major role in clotting the primary concern

with thrombocytopenia is bleeding. It is one of the most

common coagulation disorders identified in the acutely ill

adult population.

Thrombocytopenia is often associated with conditions

resulting from altered immunity such as systemic lupus

erythmatosus (SLE) and AIDS, malignancies, bone marrow

suppression, liver disease, eclampsia, splenomegaly,

hemorrhage, and massive transfusions. Also, excessive

alcohol intake and the use of some medications (i.e., the

use of thiazide diuretics in elderly) are common

precipitating causes of thrombocytopenia.

Although thrombocytopenia or low platelet count is

common, identifying the cause of low platelet count is often

Etiologic causes of thrombocytopenia are related to one of

the following five pathogenic processes:

• decreased platelet production

• decreased platelet survival

• excessive consumption of platelets

• splenic sequestration of platelets

• platelet dilution (massive volume administration)

The end result of each of these processes is an insufficient

number of platelets available for maintaining adequate

homeostasis, and therefore hemorrhage occurs. In some

disorders, the process of platelet destruction activates the

thrombocytes (platelets) and causes them to stick together

stimulating thrombosis production.

In some

thrombocytopenic states, the outcome is a potential for

increased clotting; not bleeding.

The severity of clinical signs and symptoms of

thrombocytopenia increase as platelet count falls. The

clinical presentation can be assessed on a physical exam

where internal or external bleeding signs are present.

Signs and Symptoms

Common signs and symptoms of Thrombocytopenia are as follows:

• Renal signs: Hematuria

• Laboratory signs: Platelet count is severely

• Gastrointestinal signs: Hematemesis, melena,

diminished. Red cell count and hemoglobin levels will be

hematochezia

normal. Coagulation studies will be normal.

• Neurological signs: Severe headache, nausea and/or

• Integumentary signs: Petechial hemorrhage of lower

vomiting, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, decreased

extremities, ecchymoses, gingival bleeding, spontaneous

level of consciousness.

epistaxis

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

26

Page of 8

• Miscellaneous signs: Retinal hemorrhage, heavy menses in women

Diagnoses

The diagnosis of thrombocytopenia is made by the

presence of a low platelet count and a prolonged bleeding

time. PT and aPTT will be normal. Examination of platelet

morphology can provide clues as to the origin of

thrombocytopenia.

ITP

Recall that ITP—thrombocytopenia where the origin of the

low platelet count cannot be determined—is the most

common documented etiology for thrombocytopenia. Two

other etiologies for thrombocytopenia are seen in acutely ill

patients as well— Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia

(HIT) and Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP.)

This process can happen to any patient who has had

heparin administered but is most frequently seen in the

cardiac and orthopedic populations, probably because

heparin is a common therapy in those specialties. The

heparin can be from any source — intravenous,

subcutaneous, through catheter flushes, and even through

heparin bonded catheters.

HIT is diagnosed with clinical findings and blood work. The

primary diagnosis is thrombocytopenia with an unexplained

drop (usually > 50% their baseline) somewhere between

days 5 and 10 after heparin administration. The drop may

be more rapid if the patient had been administered heparin

in the past and developed antibodies. Blood can be sent for

antibody screening to confirm HIT.

TTP

The potential etiologies for Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic

Purpura (TTP) can be congenital, idiopathic, or secondary.

HIT

Heparin Induced Thrombocytopenia (HIT) with or without

thrombus (HITT) is an uncommon immune reaction to

heparin therapy. It is a transient acquired hypercoagulable

syndrome. Because the drug heparin is made from bovine

or porcine proteins, the patient’s immune system might

produce antibodies to the antigens on the animal protein, in

turn leading to platelet destruction and thrombocytopenia.

The platelet destruction might lead to thromboemboli

development.

Thrombus development occurs in about 35-58% of patients

having HIT. The clots can be venous or arterial and have

presented as all of the following: DIC, stroke, myocardial

infarction, renal infarction, and at the sites of surgical

grafts.

Treatment for HIT is to first stop the heparin administration

and to administer a non-heparin anticoagulant until the

patient’s platelet count has returned to his or her baseline.

Caution should be taken when administering platelets to a

patient with suspected HIT. Platelet transfusions are

typically not done unless the patient has severe bleeding.

The patient should be identified as having a heparin allergy

although the incidence of a repeat of HIT with subsequent

heparin administration is unknown at this time because the

antibody development is not permanent.

The most common secondary cause is medications;

however other secondary causes are infection,

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

27

Page of 8

malignancies, autoimmune disorders, immunizations, and

hypertensive crisis.

This disorder presents with a low platelet count and a

hemolytic anemia (drop in red blood cell count from early

destruction or hemolysis.) Despite the fact that the platelet

count will be low in a person with TTP, the person may also

present with microvascular thrombi. The mechanism that

destroys the platelets also activates them and platelet

aggregation is stimulated. While systemic microvascular

thrombi may occur, the most common sites are renal and

CNS. Fever is also common. In addition to the

thrombocytopenia and hemolytic anemia, other laboratory

Another hematologic condition with thrombocytopenia

exists as well and it is called HELLP or HELLP syndrome.

This is a life-threatening condition of pregnancy seen in

hospitals with large high-risk obstetric populations. The

acronym describes the clinical presentation—Hemolysis

with Elevated Liver enzymes and Low Platelets is exactly

how these women present.

HELLP is a result of pregnancy induced hypertension (PIH)

or “preeclampsia.” The subsequent severe vasoconstriction

causes destruction of red blood cells and platelets and the

potential for ischemia to any organ bed although the

hepatic and renal systems are most commonly affected.

findings in TTP include elevated reticulocyte count and

serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH,) but normal

fibrinogen, PT and aPTT.

Treatment for TTP is to identify and stop the cause.

Antiplatelet agents are frequently given to decrease the

likelihood of clot formation. Plasma exchange,

immunosuppressive therapy, and splenectomy have also

been shown to be useful in treating TTP. Platelet

administration is not done unless the patient is bleeding

since giving a patient with TTP platelets might give them

more cells to destroy and be used for thrombus formation.

The laboratory findings include the following: low RBC,

Hemglobin, Hematocrit, and platelet count, high liver

function tests, BUN, creatinine and D-Dimer, and normal

PT and aPTT.

The treatment for HELLP is the same as for PIH; namely,

to treat the hypertension and deliver the fetus in order to

stop the cause of the PIH and prevent subsequent

complications of the vasoconstriction. Attempt to minimize

blood loss and treat and support the organ dysfunction that

might have resulted from the severe vasoconstriction.

Disorders of a Qualitative Nature – Normal Platelet Count but Abnormal Platelet Function

While Thrombocytopenia is a quantitative platelet disorder (a disorder related t platelet or thrombocyte count,) there are

qualitative platelet disorders as well. In such types of disorders, the patient might have a normal thrombyte count and yet

their platelets are not functioning normally, leading to bleeding. Two examples of qualitative platelet disorders follow:

• A patient who has taken an antiplatelet drug like

aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix,) dipyridamole (Persantine,)

and the GPIIb/IIIa inhibitors abciximab (ReoPro,)

eptifibatide (Integrelin,) and tirofiban (Aggrastat.) These

drugs disrupt platelet function, limiting the formation of a

platelet clot.

• VonWillebrand’s disease - a congenital or acquired

decrease or absence of the plasma protein co-factor

“vonWillebrand’s factor” which is needed to stabilize

clotting factor VIII and which helps fibrinogen hold platelets

together.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

28

Page of 8

The primary focus of patient management is on identifying and correcting the underlying cause of the thrombocytopenia.

This may include discontinuing any medications that may alter platelet function such as aspirin and NSAIDs. The use of

corticosteroids to increase platelet production may be indicated. The most common treatment for thrombocytopenia with

associated bleeding is the administration of human platelets.

Plasmapheresis—the mechanical removal of platelet-free plasma from the patient’s circulation— may be considered. If the

spleen is believed to be involved, a splenectomy may be performed.

Topic Three: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation Basics

While DIC is less common than anemia or thrombocytopenia, it is potentially life threatening. Disseminated Intravascular

Coagulation, or DIC, occurs when the normal coagulation and fibrinolytic mechanisms are altered and there is abnormal

activation of coagulation and secondary fibrinolysis simultaneously.

DIC occurs secondary to other major illnesses such as:

• Obstetric complications (the most common cause.)

These can include chemicals from the uterus being

released into the blood, or from amniotic fluid embolisms,

and eclampsia . Another obstetric condition which can

cause DIC is abruptio placentae.

• Sepsis, particularly with gram-negative bacteria

• Tissue trauma such as burns, accidents, surgery, and

shock

• Liver disease

• Incompatible blood transfusion reactions or a massive

blood transfusion (more than the total circulatory volume)

• Cancers, widespread tissue damage (e.g. burns,) or

hypersensitivity reactions that produce the chemicals

• Acute promyelocytic leukemia

• Viral hemorrhagic fevers

• Envenomation by some species of venomous snakes,

such as those belonging to the genus Echis (saw-scaled

vipers.)

Although the risk factors contributing to the initiation of DIC are diverse, there are three common physiologic responses.

When tissue damage, platelet damage, and endothelial damage occur, the intrinsic or extrinsic coagulation mechanism

becomes activated and microvascular thrombi develop. This is the normal response to tissue and cellular damage.

As thrombi are formed, vascular occlusion and tissue ischemia may develop affecting end organ perfusion and therefore

function. The normal physiological response to thrombi development is the fibrinolytic response, where fibrinolysis is initiated

and fibrin split products (FSP) and D-Dimer are released.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

29

Page of 8

FSPs function as anticoagulants, enhancing the breaking up of clots. The area where clot formation occurred may begin to

bleed again and then clot again. As coagulation factors are rapidly consumed, excessive bleeding results. If not reversed,

this process will result in severe blood loss and hemorrhagic shock, increased microvascular clotting,

hypoperfusion/ischemia, and multi-organ dysfunction/failure which would eventually lead to death.

The patient’s history will reveal a concurrent condition known to precipitate DIC and spontaneous bleeding in the absence of

known coagulation abnormalities:

• Unexplained petechiae, ecchymoses, and hematomas

may be present upon assessment of the skin.

• Spontaneous epistaxis, bleeding from the conjunctiva,

bleeding from the hematuria, or intracranial bleeding may

be noted.

• Unusually excessive or prolonged oozing or bleeding

following venipuncture or from existing IV sites or

wounds may be seen.

Abnormal coagulation studies will confirm the diagnosis of DIC:

• All of the following will be elevated: PT, aPTT, fibrin split products, and D-dimer. Elevation of fibrin split products in

the presence of elevated D-dimer is highly indicative of DIC.

• Platelet and fibrinogen levels will be decreased because they have been consumed in the formation of the clots.

Because DIC is secondary to other conditions, the primary focus is to identify and correct the underlying cause and support

the patient symptomatically. Depleted coagulation factors must be replaced by using packed red blood cells, fresh frozen

plasma, platelets, or cryoprecipitate. Additional treatment goals include decreasing all bleeding risks to the patient and

monitoring and treating pain aggressively.

The use of heparin to treat DIC remains controversial. Its use has never been validated with a double blind research study.

However, many believe it has a beneficial effect in deactivating the coagulation or clotting process which started the

physiological cascade of clotting and bleeding.

© 2008 American Association of Critical-Care Nurses (AACN). All rights reserved.

30

Anemia Symptoms

Lesson: Care of the Patient with Hematologic Disorders

Topic: Anemia

Cardiovascular System

Pulmonary System

Neurologic Symptoms

Gastrointestinal System

Integumentary System

Tachycardia

Palpitations

Angina

Increased cardiac output

Decreased capillary refill

Hypovolemic shock

Orthostatic hypotension

ECG abnormalities

Dyspnea on exertion

Tachypnea

Fatigue

Headache

Faintness

Light-headedness

Restlessness

Irritiability

Splenomegaly

Hepatomegaly

Cool skin temperature

Muscle cramps

Pallor of skin and mucous membranes

Dusky nailbeds

Intermittent claudication

31

Blood Component Therapy 1,2

Component

Whole blood

Red Blood Cells (RBCs)

(increase oxygen-carrying

capacity)

• Packed

• Frozen

• Washed/re-centrifuged

• Irradiated

• Fresh frozen plasma

(source of plasma proteins

for patients who are

deficient in or have

defective plasma proteins –

contains all coagulation

factors. Can be used for

plasmaphersis.)

Indications

Additional Information

Red Blood Cell Containing Components

Acute hemorrhage, most often trauma

• Less available

• Need algorithms to guide usage

• Must be ABO identical with recipient

Active bleeding: maintain volume,

• May contain approximately 20-150 mL of residual plasma

Hemoglobin stability

• May be used for exchange transfusion

Not active bleeding:

• Should not be used for volume expansion or for anemias that can be

Hgb < 5 or 6 g/dL: universal

corrected with medications (iron, vitamin B12, folic acid,

Hgb over 10 g/dL: never

erythropoietin)

Hgb >5 and < 10 g/dL: based on

• Must be ABO compatible with recipient

signs, symptoms, physiology*

• Each unit contains enough hemoglobin to ↑ concentration

approximately 1 g/dL

(hematocrit ↑ by 3 percentage points)

• Give as fast as pt can tolerate but over less than 4 hours

Plasma and Plasma Fractions

• Preoperative or bleeding patients who

• Each mL of undiluted plasma contains 1 international unit (IU) of each

require replacement of multiple plasma

coagulation factor.

coagulation factors (dilutional

• Do not use when coagulopathy can be corrected with specific therapy

coagulopathies)

(Vitamin K, cryoprecipitated AHF, or Factor VIII)

• Patients with massive transfusion who

• Do not use for volume expansion when blood volume can be replaced

have clinically significant coagulation

safely with other volume expanders

deficiencies

• Compatibility tests are not necessary

• Patients on warfarin who are bleeding or • Must be ABO compatible with recipient red cells

need to undergo invasive procedure

• Monitor with lab assays of coagulation function

before Vit K could reduce effect

• Can be given by rapid bolus infusion; otherwise over less than 4 hours.

• Patients with thrombotic thrombocytic

• Vitamin K reversal of Warfarin can take up to 6-8 hours.

purpura (TTP)

• Patients with coagulation factor

deficiencies for which no specific

plasma concentrates are available

32

• Cryoprecipitate

(source of Factor VIII,

vonWillebrand Factor,

Factor XIII)

• Control of bleeding associated with

fibrinogen deficiency

• Treatment of Factor XIII deficiency.

• DIC

• Compatibility testing is unnecessary

• ABO compatibility is preferred, Rh type not considered

• Should contain > 80 IU Factor VIII and 150 mg of fibrinogen per 15

mL of plasma

• Give over less than 4 hours.

• Laboratory studies must indicate specific hemostatic defect for use of

this product

Platelet Components

Platelets

NO bleeding present:

• Requirements increase if other coagulopathy present or if platelets not

Pooled Platelets

• Prophylaxis for CNS bleed in bone

functioning normally.

Leukocyte Reduced

marrow failure

• Check count after 1 hour in bleeding patient.

Platelets

• Prophylaxis for major surgical procedure • Compatibility testing is not necessary.

(essential for hemostasis,

• RARELY need prophylaxis for minor

• Should be ABO compatible with recipient in infants or with large

transfuse to provide

surgery

volumes of transfusion.

adequate numbers of

BLEEDING Patient:

• One unit of platelets should increase platelet count in 70-kg adult by 5normally functioning

• Transfuse to > 50,000/mm3 if possible

10,000 mm3

platelets for prevention or

• Usual adult dose is 4-8 units.

cessation of bleeding)

• Can transfuse as fast as tolerated, must be less than 4 hrs.

• Lifespan of transfused platelets = 3-4 days

• Some patients may require single donor vs. pooled platelets.

Granulocyte Components

Granulocytes

• Treatment of neutropenic patients who

• Collected by hemapheresis – each concentrate = > 1.0 x 1010

(decrease level of bacterial

have documented infections and have

granulocytes

and fungal infection in

not responded to antibiotics

• Must be ABO compatible

neutropenic patients)

• Hereditary neutrophil function defects

• Should be irradiated to prevent graft vs host disease (GVHD).

• Rarely associated with increment in patient’s granulocyte count

• Transfuse as soon as possible; each unit to be given over 2-4 hours.

• Use standard blood transfusion set.

*American Association of Blood Banks Audit Criteria

33

General Principles for Transfusion1

• All blood components must be transfused through a filter designed to remove clots and aggregates (generally a standard 170-260 micron filter).

• No medications or solutions may be routinely added to or infused through the same tubing with blood or components with the exception of 0.9%

Sodium Chloride, Injection (USP), unless a) they have been approved for this use by the FDA or b) there is documentation available to show that

the addition is safe and does not adversely affect the blood or component.

• Lactated Ringer’s, Injection (USP) or other solutions containing calcium should never be added to or infused through the same tubing with blood or

components containing citrate.

• Sterility must be maintained.

• The intended recipient and the blood container must be properly identified before the transfusion is started.

• Blood components may be warmed if clinically indicated for situations such as exchange or massive transfusions, or for patients with cold-reactive

antibodies. Warming must be accomplished using an FDA-cleared warming device so as not to cause hemolysis.

• Transfusion should be completed within 4 hours and prior to component expiration.

• Some life-threatening reactions occur after the infusion of only a small volume of blood. Therefore, unless otherwise indicated by the patient’s

clinical condition, the rate of infusions should initially be slow. Periodic observation and recording of vital signs should occur during and after the

transfusion to identify suspected adverse reactions. If a transfusion reaction occurs, the transfusion must be discontinued immediately and

appropriate therapy initiated. The infusion should not be restarted unless approved by transfusion service protocol.

• All adverse events related to transfusion, including possible bacterial contamination of a blood component or suspected disease transmission, must

be reported to the transfusion service according to its local protocol.

References:

1

American Association of Blood Banks, America’s Blood Centers, American Red Cross. Circular of Information for the Use of Human Blood and

Blood Components. http://www.aabb.org/Documents/About_Blood/Circulars_of_Information/coi0702.pdf. 2002. Accessed April 17, 2006.

2

Luce J. Blood and blood products, blood substitutes. Presentation at ACCP Critical Care Board Review, August 2005.

3

Luce J. The bleeding patient in the ICU. Presentation at ACCP Critical Care Board Review, August 2005.

4

Pagana K, Pagana T. Mosby’s Manual of Diagnostic and Laboratory Tests.3rd Ed. St. Louis: Mosby, Inc; 2006.

34

Coagulation Monitoring3,4

Monitoring

Tissue and

vascular factors

Platelets

Fibrin generation

Thrombin

generation

Indications*

DIC, abnormal platelet

volume or function,

uremia, warfarin overdose,

anti-inflammatory drugs

DIC, liver failure, massive

transfusion (dilutional

coagulopathies), platelet

disorders (ITP, TTP),

platelet function

abnormalities (drugs such

as aspirin, IIB/IIIA

inhibitors) uremia, HIT

DIC, liver failure, massive

transfusion

DIC, heparin

administration, massive

transfusion, acquired Vit K

deficiency, HIT, warfarin

administration

DIC, anticoagulation

therapy

Measurement

Bleeding time

Normal

1-9 minutes (Ivy method)

Critical Values

> 15 minutes on repeat eval

Platelet count

Adult:150,000 – 400,000/mm3

Child: 150,000 – 400,000/mm3

Infant:200,000 – 475,000/mm3

Premature Infant: 100,000-300,000/mm3

Newborn: 150,000 – 300,000/mm3

Platelet

Antibodies

Fibrinogen

None identified

• > 10,000/mm3 prevents

spontaneous CNS hemorrhage

• > 50,000/mm3 prevents most

medical/surgical bleeding

• >100,000/ mm3 when

anticipating bypass, vascular,

other major surgery.

PT

PTT

Adult: 200-400 mg/dL or 2-4 g/L (SI units)

Newborn: 125-300 mg/dL

11.0-12.5 seconds; INR 1.5-2.0

APTT: 30 - 40 seconds

PTT: 60 – 70 seconds

<100 mg/dL can be associated

with spontaneous bleeding

Therapeutic INR = 2-3.5

Therapeutic PTT: 1.5 – 2x normal

Critical values: APTT > 70 secs

PTT > 100 secs

Factor Assays

Normals vary according to specific factor

Unclotting or

FDP

<10mcg/mL or <10 mg/L (SI units)

Critical value: >40 mcg/mL

Thrombosis

D-dimers

Qual – negative

Quant <250ng/mL or <250 mcg/L (SI units)

indicators

*Listing not all inclusive

DIC – Disseminated intravascular coagulation ITP – Immune thrombocytopenic purpura TTP – Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura

HIT - Heparin induced thrombocytopenia PT – Prothrombin time PTT – Partial thromboplastin time FDP – Fibrin degradation products

35

Risk Factors for DIC

Lesson: Care of the Patient with Hematologic Disorders

Topic:

GENERAL

CLASSIFICATIONS

Anemia

PRIMARY

EVENT/DISORDER

PRIMARY

EVENT/DISORDER

Tissue Damage

Major Surgery

Major Trauma

Heat Stroke

Head Injury

Burns

Transplant Rejection

Extracorporeal Circulation

Snake Bites

Obstetric

Complications

HELLP

Amniotic Emboli

Abruptio Placenta

Fetal Demise

NS Abortion

Eclampsia

Placenta Accreta

Placenta Previa

Shock States

Cardiogenic Shock

Septic Shock (severe

infection or inflammation)

Hemorrhagic Shock

Dissecting Aneurysm (large

vessels)

Massive Blood and Volume

Resuscitation

Drowning

Anaphylaxis

Neoplasms

Acute & Chronic Leukemia

Acute & Chronic Lymphoma

Solid Tumors

Hamangiomas

Hematologic

Disorders

Thrombotic

Thrombocytopenic Purpura

(TTP)

Transfusion Reactions

Collagen Vascular

Disorders

Thrombocythemia

Sickle Cell Crisis

Specific System

Dysfunction

Acute & Chronic Renal Dis

Ulcerative Colitis

DKA, Acid Ingestion

HIV Disease

ARDS

Acute Pancreatitis

Liver Dysfunction/Failure

SIRS & MODS

Pulmonary Embolism

Fat Embolism

36

Care of the Patient with

Hematologic and Immunologic

Disorders

Lesson: Pathologic Conditions

Topic: Anemia

Practice Pearls

Etiologies for Anemia

G6PD deficiency is an inherited condition in which the body doesn't have enough of the

enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, or G6PD, which helps red blood cells

(RBCs) function normally.

G6PD deficiency is most common in African-American males. Many African-American

females are carriers of G6PD deficiency, meaning they can pass the gene for the

deficiency to their children, but do not have symptoms; only a few are actually affected

by G6PD deficiency. People of Mediterranean heritage, including Italians, Greeks,

Arabs, and Sephardic Jews, also are commonly affected. The severity of G6PD

deficiency varies among these groups–it tends to be milder in African-Americans and

more severe in people of Mediterranean descent.

Symptomatic Anemia

The hemoglobin or red blood cell levels that are indicative of anemia have not been

firmly established. This is a debate that continues in the critical care and hematology

literature. When dealing with anemia, the focus should be on the clinical symptoms of

the patient rather than the hemoglobin or RBC value.

Anemia Management

Transfusion Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI) is defined as an acute lung injury that is

temporally related to a blood transfusion; specifically, it must occur within the first six

hours following a transfusion. It is the third leading cause of transfusion-related deaths.

The etiology is still not known, but it is thought to be a result of the presence of

antibodies in multiparous females or patients who have received previous transfusions.

Symptoms include dyspnea, hypotension and fever.

37

Care of the Patient with

Hematologic and Immunologic

Disorders

Lesson: Pathologic Conditions

Topic: Thrombocytopenia

Signs and Symptoms of Thrombocytopenia

With a platelet count of 50,000/mm3, increased bruising and bleeding following minor

trauma may be noted. Petechiae and purpura manifest as the platelet count falls below

50,000/mm3. When platelet counts fall dangerously low, below 20,000/mm3,

hemorrhage occurs, particularly in the mucosa, deep tissues, and intracranial space.

38

Care of the Patient with

Hematologic and Immunologic

Disorders

Lesson: Pathologic Conditions

Topic: Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

Use of Heparin

There are currently several treatments that have not been approved by the FDA being

used to treat DIC. These are Activated Protein C, Antithrombin III and rhFVIIa. These

treatments are currently being studied and showing promise in the treatment of DIC.

39

Care of the Patient with

Hematologic and Immunologic

Disorders

Lesson: Pathologic Conditions

Topic: Lesson Review

Lesson Summary

Emerging science is strengthening the connection between sepsis and DIC. Assessing

for the presence of DIC and early intervention are increasingly common in the critically

ill.

40

Care of the Patient with

Hematologic and Immunologic

Disorders

Glossary

Cryoprecipitate

the precipitate that forms when plasma is frozen then thawed.

Particularly rich in fibronectin and blood clotting Factor VIII.

Cytokines

non-antibody proteins secreted by both inflammatory leukocytes and

some non-leukocytic cells that act as intercellular mediators. They

differ from classical hormones in that they are produced by a

number of tissue or cell types rather than by specialized glands.

They generally act locally in a paracrine or autocrine (rather than

endocrine) manner.

D-dimer

the cross-linked fibrin degradation fragment. Elevations in this

fragment are seen in primary and secondary fibrinolysis, during

thrombolytic or defibrination therapy with tissue plasminogen

activator, as a result of thrombotic disease such as deep-vein

thrombosis, pulmonary embolism or DIC, in vase-occlusive crisis of

sickle cell anemia, in malignancies, and in surgery.

Ecchymosis

a small hemorrhagic spot, larger than a petechia, in the skin or

mucous membrane forming a non-elevated, rounded or irregular,

blue or purplish patch.

Erythropoietin

a Glycoprotein (46 kD) hormone produced by specialized cells in the

kidneys that regulates the production of red blood cells in the

marrow. These cells are sensitive to low arterial oxygen

concentration and will release erythropoeitin when oxygen is low.

Erythropoeitin stimulates the bone marrow to produce more red

blood cells (to increase the oxygen-carrying capacity of the blood.)

The measurement of this hormone in the bloodstream can indicate

bone marrow disorders or kidney disease. Normal levels of

erythropoietin are 0 to 19 mU/ml (milliunits per milliliter.) Elevated

levels can be seen in polycythemia rubra vera. Lower than normal

values are seen in chronic renal failure. Recombinant erythopoietin is

now being used therapeutically in patients.

41

Extrinsic

an inherited disorder that causes abnormal blood clotting due to the

congenital absence of one of the 20 different plasma proteins

involved in the coagulation process. Symptoms include bleeding of

the gums, nosebleeds, easy bruising, bleeding in muscles or joints,

and excessive menstrual bleeding. Treatment includes the

administration of plasma concentrates of Factor VII (extrinsic factor

i.e. dietary vitamin B12.)

Fibrin split

products

the insoluble protein formed from fibrinogen by the proteolytic

action of thrombin during normal clotting of blood. Fibrin forms the

essential portion of the blood clot.

Hematochezia

the passage of bright red blood per rectum. This symptom may be

associated with hemorrhoids, anal fissure, rectal polyp, cancer,

diverticulitis or inflammatory bowel disease.

Hematuria

the finding of blood in the urine

Hemoptysis

the expectoration of blood or of blood stained sputum

Intrinsic

a mucoprotein normally secreted by the epithelium of the stomach

and that binds vitamin B12; the intrinsic factor/B12 complex is

selectively absorbed by the distal ileum, though only the vitamin is

taken into the cell.

Lupus

erythmatosus

skin disease in which there are red scaly patches, especially over the

nose and cheeks. May be a symptom of systemic lupus

erythematous (a disease of humans, probably autoimmune with

antinuclear and other antibodies in plasma.) Immune complex

deposition in the glomerular capillaries is a particular problem.

Lymphoid cells

cells derived from stem cells of the lymphoid lineage. Large and

small lymphocytes, plasma cells.

Melena

the passage of black and tarry (sticky) stools stained with blood

pigments or with altered blood

42

Menorrhagia

excessive uterine bleeding occurring at the regular intervals of

menstruation, the period of flow being of greater than usual duration

Morphology

a study of the configuration or structure of animals, cells, tissue, etc.

Myeloid cells

one of the two classes of marrow derived blood cells, includes

megakaryocytes, erythrocyte precursors, mononuclear phagocytes

and all the polymorphonuclear granulocytes. That all these are

ultimately derived from one stem cell lineage is shown by the

occurrence of the Philadelphia chromosome in these, but not

lymphoid, cells. Most authors tend, however, to restrict the term

myeloid to mononuclear phagocytes and granulocytes and

commonly distinguish a separate erythroid lineage.

Petechiae

small red spots on the skin that usually indicate a low platelet count.

Pinpoint, non-raised, perfectly round, purplish red spots caused by

intradermal or submucous hemorrhage.

Plasmapheresis

centrifuging blood that has been removed from the body to separate

the cellular elements from the plasma

Stem cells

relatively undifferentiated cells of the same lineage (family type)

that retain the ability to divide and cycle throughout postnatal life to

provide cells that can become specialized and take the place of those

that die or are lost