Evaluation of software for the hydraulic analysis of highway culverts

advertisement

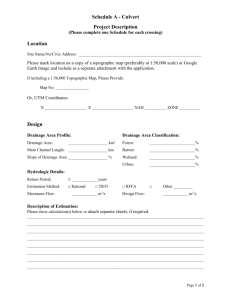

Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 Evaluation of software for the hydraulic analysis of highway culverts Vassilios A. Tsihrintzis* & Jose Luis Oliveros^ "Department of Environmental Engineering, Democritus University of Thrace, Xanthi 671 00, GREECE, Email: tsihrin@platon.ee.duth.gr, tsihrin@otenet.gr * Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Florida International University, Miami, FL 33199, USA Abstract Several methods have been developed for the analysis and design of highway culverts, including those by the US Federal Highway Administration, the US Corps of Engineers, state and local agencies and private companies. This study has collected, described, evaluated and presents the most popular methods and software used today in the USA. Description and evaluation include: technical capability, ease in use, cost and other factors. Major part of the evaluation is comparison between predicted and measured velocity, discharge and upstream/downstream water surface elevations for several culverts located at a study area in South Florida, aiming at further evaluating the technical capability of the various methods and software. It was found that the pieces of software that receive the overall highest score were the WSPG, HEC-2 and SWMM-EXTRAN. 1 Introduction and background Hand calculation nomographs, tables and procedures to analyze and design culverts have been developed by the US Federal Highway Administration' (FHWA). This method was used for many years until the implementation Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 546 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII of computers and software to the engineering field. Computers offer advantages over hand calculation methods, including: variables can be easily changed, results can be obtained faster, and alternatives can be tested to optimize the design. Furthermore, calculations may be more accurate decreasing round off errors, and the output can be saved and printed in a format that is easy to read and can serve as part of the final documentation (Oliveros^). Finally, computers today are inexpensive tools which increase efficiency and effectiveness in highway drainage design (Richards^). Because of these advantages, different pieces of software have been developed for engineering applications in culvert analysis and design, something that brought up the need to comparatively evaluate computer program performance. Previous studies on this have been very few. For example, a previous culvert software comparative study by Khine/ who tested the US Geological Survey (USGS) Culvert Program, the FHWA HY8 and the US Corps of Engineers HEC-2, came to the conclusion that the results from these three programs are close to each other because the equations used are essentially the same. Nevertheless, the suggested values of the various coefficients are different resulting in slightly different results. Also, if the type of flow is full flow with free outlet condition, the results from the hand calculations should be used instead of HEC-2 and HY-8. In this study, an extensive critical evaluation of software was performed and comparative rating is provided. In order to evaluate software and methods, it was also necessary to collect field data such as flow, velocity, headwater and tailwater elevations, culvert geometric characteristics and invert elevations. The following computer programs were tested: WSPG/ CulvertMaster,* StormCad/ Culvert for Windows,* HydroCalc/ HY-8," HYCLV," HEC-2,^ THYSYS^ SWMM-EXTRAN," andXP-SWMM/s 2 Study area and methodology As mentioned, field data was collected to evaluate the technical capability of the culvert software. This was done at Taylor Slough in the Everglades National Park (ENP) in South Florida, at various culverts crossing State Road 9336. This road, which is the main road crossing ENP, spans across Taylor Slough, interrupting its free water flow. Twenty three water conveyance structures were constructed under the road to facilitate the movement of water along the slough. Among these 23 structures, there is the Taylor Slough Bridge (Structure 19) and 22 culverts. For the purpose of Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII 547 this research, three culverts have been selected. A box culvert (Structure 18), 8 feet wide and 4 feet deep, located on the east side of the bridge and two 36-inch circular culverts (Structures 17 and 22) (Sikkema et al.'*). The reason for the selection of these structures is that they are located at the deeper part of the slough conveying most of the flow (i.e., approximately 86% of the total flow goes through structures 16 to 22, including the bridge). Therefore, these culverts carry flow for relatively longer time during the year compared to the other hydraulic structures. Culverts 17 and 22 have the same diameter (36-inch), but the second one has significantly more sediment deposition than thefirstone, which makes the reduced cross section an important point to test the various computer programs. The field data collection task was divided into two parts: (1) structure surveying; and (2) hydraulic data collection (i.e., upstream and downstream water surface elevation, flow velocity and sediment deposition height). Extensive field work was performed to acquire the geometric data for the three structures. The length and the invert elevations of the inlet and outlet of the culverts were estimated using standard surveying techniques (i.e., tape measuring and leveling). As a reference point was taken a second order benchmark located on the east side of Taylor Slough Bridge. The length of each culvert was measured by placing the measuring tape across the road along the pipe. All numbers and procedures were recorded in a field book. The hydraulic data collection comprised two parts: water level measurements and water velocity measurements. Culvert 17 (circular) and 18 (box) do not have a water surface elevation gage. Therefore, the inlet/outlet water surface elevations were obtained by measuring the vertical distance from the crown of the culvert to the water surface (above or below the crown). If the water surface was above the crown, the measured vertical distance was added to the corresponding inlet/outlet invert elevation, the inside height and the thickness of the culvert to obtain the water surface elevation. On the other hand, if the water level was below the crown, the measured vertical distance was subtracted from the inside height and added to the corresponding inlet/outlet invert elevation. Also, a rod was used to measure the inside diameter/depth of the culverts to determine sediment height. Culvert 22 has water surface elevation gages at both the inlet and outlet. Therefore, the water level was measured directly. All measured water surface elevations were checked against the water level continuously recorded at Taylor Slough Bridge which is done using a continuous batterypowered level measuring device (Omnidata Potentiometer/Pulley Water Level Sensor, Model ES-310 C). This device is connected to a Campbell Wiring and Control Module (Model CR10WP) containing a Campbell Storage Module (Model SM 192) (Sikkema et al.'*). Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 548 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII Water velocity measurements were made at the inlet of the structure when detectable flow occurred. Most data was obtained during the wet season (May through October) when considerable flow occurs, although some measurements were also made during the dry season (November through April). For velocity measurements, a Marsh-McBimey Model 201 electromagnetic flowmeter with the appropriate rod, was used. Velocity measurements were performed using standard USGS techniques (Rantz et al.^) using the 0.6 or 0.2 and 0.8 water depth criteria. When measuring the circular culverts the velocity sensor was set at 0.6 of the water depth (one point only). However, when measuring water velocity in the box culvert, the cross section was divided into three lateral subsections of approximately 2.67 feet each, the sensor was set at 0.2 and 0.8 of the water depth if that was greater than 2.5 feet (six points total), or at 0.6 of the water depth when the water depth was less than 2.5 feet (three points total). The effectiveness of this method has been evaluated by Tsihrintzis et al.^ For the box culvert, the distances from the top of any deposited sediment to the soffit of the culvert were also measured for each mid-section bay and used with the span widths to calculate the effective cross section. The area of a given subsection within the box culvert was calculated using its width and the average subsection depth (Sikkema et al.^). Velocity was computed as the average of two subsection measurements (0.2 and 0.8 of the depth), or as one measurement at 0.6 of the depth. Subsection discharges were then added to compute total discharge and cross-sectional average velocity. The two circular culverts selected for the study were 3 feet in diameter. The cross-sectional area, taking into account any deposited sediment, was derived based on geometry, and the average velocity based on the velocity measurement that was taken at the 0.6 of the water depth measured from the water surface. If the water level was higher than the soffit of the culvert, the velocity measurements were made at a position of 0.6 of the culvert diameter measured from the soffit of the culvert and discharge was computed as for the box culverts (Sikkema et al.^). Finally, an average Manning's n was used in the study based on the wetted perimeter comprising concrete and sediment. For the computation, equations presented by Chow/* based on the wetted perimeter to the 1.5 power, were employed. Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII 3 549 Results and conclusions The computer programs tested in this paper could be divided in two main groups: (1) the software designed specifically for culvert analysis and design, and (2) software developed for storm drain energy grade line and hydraulic grade line computation, that could also be used for culverts. From these two groups, there are programs that run in WINDOWS Mode or DOS Mode. From experience, it is known that software operating in WINDOWS are easier to use and faster to learn. The results predicted by groups (1) and (2) software are absolutely comparable because the hydraulic principles used are similar. However, there were observed general disadvantages for WINDOWS type of software. First, they are less flexible when the user is inputting data, i.e., it allows the user to use just the values pre-defined by the software in almost all data input windows (for example, cross-section shape and size, minor loss options, entrance and outlet configurations, Manning's n coefficient, culvert material, etc). Second, the system requirements to run any DOS Mode operating software are easily satisfied by any PC computer manufactured today. On the other hand, the WINDOWS Mode operating software usually needs a fast Computer Processing Unit (CPU) and a good Random-Access Memory (RAM) size (sometimes up to 16 megabytes may be required). Finally, the manuals for software running in DOS are usually more complete and comprehensive explaining theory and step-by-step input format. On-line help, which is a characteristic of WINDOWS operating software, usually does not provide the necessary information, and theory that the user may need is often missing. Input files were prepared for the 11 pieces of software tested, to describe the geometry of the culvert as surveyed and the flow conditions. A total 38fieldexperiments and simulations were performed. Output from each software was mainly the following: upstream water surface elevation and velocity. The evaluation of the technical capability of each piece of software in predicting water surface elevation and velocity was done by plotting predicted quantities versus measured ones and fitting a straight regression line through the data. The slope of the straight line and the correlation coefficient are measures of the goodness of predicted data. In fact, the closer the slope is to 1, the closer the predicted values are to the measured ones. Values of the slope less than 1 imply overall underprediction and values of the slope greater than 1 imply over-prediction. The correlation coefficient has also to be as close to 1 as possible, indicating scattering of the data around the regression line. Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 550 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII When plotting the headwater data for the three culverts, the best prediction slope was given by THYSYS (0.9829) and the lowest value was reported by SWMM-EXTRAN (0.9688). The other software gave: WSPG: 0.9758, CulverMaster: 0.9737, StormCad: 0.9703, Culvert for Windows: 0.9228, HydroCalc: 0.9727, HY-8: 0.9282, HYCLV: 0.9786, HEC-2: 0.9695, XP-SWMM: 0.9732. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.8123 to 0.9322. Velocity prediction slopes were close to 1.0 for WSPG (0.9970) and HEC-2 (0.9695) when taking into account all culverts. For the rest of the software the slopes were about 0.9700. The exact values were the following: CulverMaster: 0.9689, StormCad: 0.9663, Culvert for Windows: 0.9690, HydroCalc: 0.9616, HY-8: 0.9690, HYCLV: 0.9896, THYSYS: 0.9680, SWMM-EXTRAN: 0.9676, XP-SWMM: 0.9410. The correlation coefficients ranged from 0.9962 to 0.9998. Other comments from the comparison include: SWMM-EXTRAN does not take into account minor losses. Therefore, adjustments need to be made in the input file to make up for that deficiency. Tsihrintzis et al.^ describe a method to do this. Most software, except WSPG and HEC-2, can not analyze a culvert with irregular section. When there is sediment deposition, the cross-section of the culvert is not a circle or a box anymore. WSPG and HEC-2 can analyze irregular sections described by X-Y coordinates (up to 99 coordinates for WSPG and 100 for HEC-2) in order to minimize calculation errors. As opposed to HY-8, which just can take up to 19 coordinates to define a section. WSPG and HEC-2 predictions were among the best ones. On the other hand, HEC-2 inputfilesare laborious and take a long time to put together a culvert irregular section. SWMMEXTRAN shows increasing error in continuity when the tailwater elevation is lower than the crown of the culvert. HYCLV did not run for circular culverts when the tailwater elevation was lower than the crown of the culvert, and its buried pipe option seems to work for buried depths greater than 0.13 feet. Some of the studied programs do not perform calculations with zero or adverse slopes, which is the case of HydroCalc (slope range = 0.0001 to 1.0000), Culvert for Windows, CulvertMaster and HYCLV. HydroCalc and HY-8 do not produce output calculation report as others do. HY-8 outputfilescan be saved, but HydroCalc input/outputfilescan not be saved. HY-8 seems to give erratic predictions when the given tailwater is very low. It gives as output a default value for headwater predictions when very low tailwaters are used. It was also observed, that storm drain software gives as good or better output than special culvert analysis and design software because some of the storm drain programs allow the user to enter irregular sections due to sediment deposited and because the hydraulic principles are the same. Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII 551 These discussions lead to an overall ranking of the software, based on the following categories: easiness in input preparation, presentation of output, accuracy in velocity and headwater predictions, capability to analyze irregular or various types of sections, adverse/horizontal slope capability, manual completeness/technical support, various additional options and features, price and system requirements. The ranking in each category was done as 1 (fair), 2 (good) and 3 (excellent). The scores were added and the highest overall score (including technical capability as a category) was obtained by: WSPG, HEC-2 and SWMM-EXTRAN. They were followed by StormCad and THYSYS. The last software in the ranking were HydroCalc and HY-8. Although SWMM-EXTRAN and XP-SWMM are based on the same theory, XP-SWMM ranked lower because of the lack of detail in the user's manual and the additional system requirements. Nevertheless, their predictions were close to each other except for velocity. References [ 1 ] Herr L. A. & Bossy H.G. Hydraulic charts for the selection of highway culverts, U.S. Department of Transportation, Federal Highway Administration, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington D.C., USA, 1965. [2] Oliveros, J.L., Critical evaluation of software and methods for highway culvert analysis and design, Masters Thesis, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Florida International University, Miami, Florida, USA (Major professor: Vassilios A. Tsihrintzis), 1997. [3] Richards, D.L., Microcomputers in highway drainage design, Proceedings of the Specialty Conference Hydraulics and Hydrology in the Small ComputerAge, ASCE, Lake Buena Vista, Florida, USA, August 12-17, Vol. l,pp. 54-59, 1985. [4] Khine M., Standardization of culvert flow computations, Hydraulic Engineering, Proceedings of the 1991 National Conference, ASCE, Nashville, Tennessee, USA, July 29-August 2, pp. 109-114, 1991. [5] Shahin, S.J., Pederson, G.J. & Schaeffer, R.A. User Manual: WSPG -Water Surface and Pressure Gradient hydraulic analysis system, Los Angeles County, distributed by Woodcrest Engineering, Riverside, California, USA, 1979. [6] Haestad Methods, CulvertMaster for Windows user's guide, Waterbury, Connecticut, USA, 1995. Transactions on Ecology and the Environment vol 17, © 1998 WIT Press, www.witpress.com, ISSN 1743-3541 552 Computer Methods in Water Resources XII [7] Haestad Methods, StormCadfor Windows user's guide, Waterbury, Connecticut, USA, 1995. [8] Water Engineering Software Solutions, Culvert for Windows user's manual, XP Software, Tampa, Florida, USA, 1994. [9] Dodson & Associates, HydroCalc User's Manual and Program Reference, Houston, Texas, USA, 1989. [10] GKY & Associates, Hydrain-integrated drainage design computer system, Federal Highway Administration. Vol. VI. HY-8 -Culverts, 1994. [11] GKY & Associates, Hydrain-integrated drainage design computer system, Federal Highway Administration. Vol. IV. HYCLV-Culverts, 1994. [12] U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, HEC-2 "water surface profiles user's manual, The Hydrologic Engineering Center, Davis, California, USA, 1982. [13] Texas State Department of Highway sand Public Transportation, User Manual for Texas Hydraulic System, Austin, Texas, USA, 1977. [14] Roesner, L.A., Aldrich, J.A. & Bamwell, T.O., Storm Water Management Model User's Manual Version 4, Addendum IEXTRAN, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Athens, Georgia, USA, 1988. [15] XP Software, XP-SWMM, Stormwater Management Model with graphical interface, Version 2.0, Vol. 1 and 2, XP Software, Tampa, Florida, USA, 1995. [16] Sikkema, D.A., Schardt, G.W. & Rehrer, R.G., Procedures used for estimating daily discharge at Taylor Slough, Everglades National Park, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, Everglades National Park, Homestead, Florida, USA, 1994. [17] Rantz, S.E. et al. Measurement and computation of streamflow: computation of discharge, Volume 2, US Geological Survey, WaterSupply Paper 2175, United States Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C., USA, 1982. [18] Tsihrintzis, V.A., Sikkema, D., Levinson, M. & Oliveros, J.L., Discharge measurement and prediction in wetlands, Proceedings of the North American Water and Environment Congress '96, ASCE, June 22-28, Anaheim, California, On CD-ROM, 1996. [19] Chow, V.T., Open-Channel Hydraulics, McGraw-Hill Publishing Company, New York, USA, 1959. [20] Tsihrintzis, V.A., Vasarhelyi, G.M. & Lipa, J., Hydrodynamic and constituent transport modeling of coastal wetlands, Journal of Marine Environmental Engineering, 1(4), pp. 295-314, 1995.