BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

Larry Beason

Ethos and Error: How Business People

React to Errors

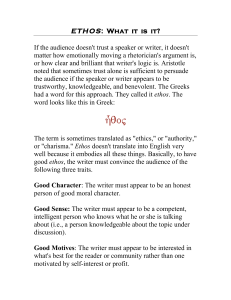

Errors seem to bother nonacademic readers as well as teachers. But what does it mean

to be “bothered” by errors? Questions such as this help transform the study of error

from mere textual issues to larger rhetorical matters of constructing meaning. Although

this study of fourteen business people indicates a range of reactions to errors, the findings also reveal patterns of qualitative agreement—certain ways in which these readers

constructed a negative ethos of the writer.

A

dhering to conventions for mechanics and usage is just one part of writing, yet this sub-skill has long been the subject of debate—especially since the

1970s when researchers and teachers such as Mina Shaughnessy challenged

the significance of error-free writing. In 1975, Isabella Halstead suggested errors should be important only in the sense that they can impede the communication of ideas (86). Not all teachers share Halstead’s perspective, but this

position certainly appeals to many researchers and teachers alike. Years after

Halstead’s suggestion, Susan Wall and Glynda Hull asked fifty-four English

teachers to name what they believed to be the most serious errors and to explain why they were serious. Nearly three-quarters of the responses indicated

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

33

Copyright © 2001 by the National Council of Teachers of English. All rights reserved.

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

the errors were serious “because they got in the way of effective communication of meaning” (277), a justification consistent with Halstead’s position.

Perhaps this is the way it should be, with errors being relatively low-level

concerns unless they impede understanding of a text. But do nonacademic

readers respond in this fashion? We

I do not believe students can understand error teach writing for many reasons, but if

unless they and teachers alike better comprehend one goal is to prepare students to write

error in terms of its impact—not just textual effectively once they leave college, we

conventions defining errors, not just categories or should consider nonacademics’ rerankings of errors, but the ways in which errors sponses to error. Our effectiveness, permanage to bother nonacademic readers. haps our ethos, can be impeded if we

stress matters that other professionals

see as trivial—or if we trivialize points they deem consequential. This is not to

say that teachers must always mirror other people’s responses to error, but we

at the very least need to know if the messages we send students will be reinforced or negated by how other professionals read errors.

Put another way, I do not believe students can understand error unless

they and teachers alike better comprehend error in terms of its impact—not

just textual conventions defining errors, not just categories or rankings of errors, but the ways in which errors manage to bother nonacademic readers. We

must understand the experiences of readers as they encounter error, for errors

are created in the mind as much as in the text. To assist in this understanding,

this study attempts to define major variables associated with negative reactions to errors appearing in business writing.

Researchers have examined how business professionals react to errors,

but mostly in terms of how serious or benign errors seem to be. In one of the

most comprehensive studies, Donald Leonard and Jeanette Gilsdorf investigated how 133 vice presidents in business and 200 members of the Association

for Business Communication ranked forty-five types of errors. The survey

shows, on the one hand, that the severity of an error is shaped by the reader’s

context; for instance, executives were not as bothered by errors as were academics. On the other hand, the rankings indicate much agreement among readers in diverse situations about the relative seriousness of certain errors, a finding

supported by Maxine Hairston’s survey almost a decade earlier.

Such large-scale surveys show that errors are often bothersome in the

workforce, but we do not fully understand why they are disturbing. If Halstead’s

stance were to be extended beyond classroom situations, nonacademics would

perceive errors as problematic only when they are obstacles to communication

34

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

of meaning. This position, although reasonable in some educational contexts,

does not take into account the judgments that people—rightly or wrongly—

make about writers who create errors. Indeed, even Wall and Hull’s aforementioned study found that 11 percent of the teachers’ reactions to errors focused

not on the readability of the text, but on the teachers’ belief that errors indicated a shortcoming with the writer’s education (277). Such a concern is understandable when education is a daily concern, but what might account for

nonacademics’ reactions, such as how business people see errors as evidence

of the writer’s ethos? I believe most teachers and students would acknowledge

that errors can both interfere with comprehension and harm a writer’s credibility, but if our students go on to write for various business communities, we

need a better understanding of these

problems as they are manifested in these Errors must be defined not just as textual

features breaking handbook rules but as mental

contexts.

In particular, we need to understand events taking place outside the immediate text.

more completely how a reaction to error

is, as Joseph Williams has indicated, a matter of interpretation that can vary

greatly from reader to reader. If there is substantial agreement among professionals’ interpretations, we might know which errors to focus on and why these

should be avoided. If interpretations vary widely, there might be little we can

do to prepare students—except tell them that each reader has his or her own

pet peeves. The present study reveals neither complete accord nor complete

chaos in how readers react. Despite a disconcerting amount of disagreement,

patterns of agreement can be seen, but only if teachers and students alike keep

in mind that errors involve more than perceived flaws in a text. Errors must be

defined not just as textual features breaking handbook rules but as mental

events taking place outside the immediate text. Defining error as simply a textual matter fails to forefront the “outside” consequences of error, especially the

ways in which readers use errors to make judgments about more than the text

itself. By considering these types of interpretation, we can in fact locate areas

of agreement about which students should be aware if they are to write effectively.

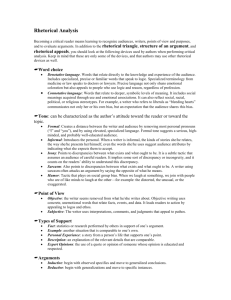

To study this interpretative process at the level of the individual reader

and to explore the variety of elements constituting a person’s reaction to error,

I examined how fourteen business people responded to errors. That is, I focused on a few individuals so that I might investigate a highly individualistic

process. But I found that readers’ interpretations of error were not so idiosyncratic that there were no similarities at all. Despite frequent variation in some

35

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

regards, this study revealed recurring elements of interpretation among these

readers. Certain types of reactions were common even though these might not

occur with the same error or to the same degree. After discussing quantitative

results in both aggregate and individual forms, I offer a synthesis of these individual reactions to indicate that, while there are no quantitative formulas for

anticipating a reaction to error, there seem to be principal qualities that account for people’s negative reactions to errors in business discourse.

Subjects

This research is based on fourteen subjects—an arbitrary number, but one

that proved manageable yet large enough to allow me to consider individuals

in various businesses. Although part of my research involves a questionnaire, I

should emphasize that overall this study is intended to generate variables associated with error response—not to quantify comprehensively the reactions

of a population. This study, in other words, does not involve an extensive number of subjects; instead the focus is on a few people whose individual reactions

I examined in some depth.

I did not use stratified sampling, despite my first impulse to select subjects with varying ethnic backgrounds. Such sampling would be appropriate

for a larger survey, but, given the sample size, I wanted to avoid generating

data that might be misconstrued as indicating that certain ethnic groups respond one way, others another way. Determining such correlations would call

for a different study with a sample large enough to represent diverse ethnic

groups. Subjects for this study come from one ethnic group, white Americans

from two regions of the US. Halfway through this study, I accepted a teaching

position across the country. Consequentially, seven subjects are from Spokane,

Washington, and seven are from Mobile, Alabama (each subject lived most or

all of his or her life in these respective locales). As noted later, geographic distribution had little effect on the results despite notable dialect differences between speakers from these two regions. Nonetheless, I believe all results should

be interpreted keeping in mind the demographic constraints as well as the

need to determine what role—if any—ethnicity, locale, and other individual

characteristics play in people’s reactions to error.

Using purposive sampling (Merriam 48–49), I selected fourteen subjects

who engaged in both daily reading of business documents and frequent (daily

or almost daily) writing in connection with their organization. I asked colleagues and acquaintances to suggest possible subjects, resulting in a list of

males and females in various roles. All were in the private sector, and I stayed

36

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

Figure 1: Subjects

Spokane subjects

Betty:

Human Resources Partner for a regional water/power company (deals with

benefits, hiring, conflict resolution).

Daryn: Vice President of Investments and Branch Manager for a national

investment firm.

Donna: Community Relations Person and Administrative Assistant to District

Service Manager for a national banking corporation.

Eric:

Regional Manager of Corporate Communications for a national

automobile club.

John:

Computer Programmer Analyst for a local software company.

Martin: Lab Manager of Analytical Services for a gold-mining company.

Susan: Assistant Regional Manager for a regional banking corporation.

Mobile subjects

Charles: Senior Agent for an insurance company.

Dee:

Accountant for a worldwide distributor of religious music.

Jan:

Vice President and Branch Manager for a regional banking corporation.

Jean:

Assistant Administrator for Human Resources Office at a health-care

institution.

Lee:

Assistant Vice President and Branch Manager for another regional banking

corporation.

Nick:

Digital Graphics Specialist for a graphics and publishing company.

Ralph: Real Estate Broker and Manager of a real estate office.

with this realm rather than broadening the study to include organizations such

as charities, social action groups, and the government. Seven of the suggested

subjects agreed to participate, and seven others did not because they lacked

time (four individuals) or no longer wrote or read much as part of their job

(three individuals). However, these latter seven suggested colleagues who agreed

to participate and who met the criteria. Finance (banking and investment) is

represented more than any other calling, but the subjects’ duties varied sufficiently to avoid duplication. Using pseudonyms, Figure 1 describes all subjects.

Procedures

For the first phase of this study, fourteen business people completed a questionnaire to rank twenty errors. For the second phase, I individually interviewed

each subject to obtain an in-depth account of the subject’s reactions.

37

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

Using the questionnaire, subjects first indicated the extent to which they

were bothered by each error, thereby gauging the error gravity of twenty preselected errors. Each error was set off with boldface so subjects could rank it

using a 1–4 scale, with 1 being the least bothersome. This format results in a

limitation often found in the related research (e.g., Greenbaum and Taylor;

Hairston; Leonard and Gilsdorf; Long). Any questionnaire that focuses respondents’ attention on gauging error gravity or on individual sentences known to

contain errors can alter readers’ natural responses. Certainly, a naturalistic

design requiring subjects to locate the errors for themselves could provide useful results, but I chose to boldface errors for two reasons. First, a pilot version

of this study indicated respondents needed to understand my focus was not

on testing their own proficiency with usage, grammar, or writing. Such apprehension and self-consciousness can produce unnatural results, as well as make

respondents less willing to engage in further discourse during follow-up interviews. Boldfacing errors helped subjects understand that my purpose was not

to test them, but to understand their viewpoint. Second, the primary goal for

using the questionnaire was to provide a tangible mechanism by which I could

explore these subjects’ reading processes. Barbara Tomlinson describes the

misleading information that writers can provide when they attempt to generalize about their writing processes instead of describing recent, specific instances (434–36). Readers, too, can face problems when researchers ask abstract

questions about how they react to texts, so I used the questionnaire to focus

the interviewees’ attention on recent encounters with specific errors. Boldfacing

the errors provided a concrete, as well as nonthreatening, means by which the

subjects and I could engage in this dialogue.

To create the questionnaire, I revised a business document to produce

five versions, with each version containing four examples of one type of error.

In case the ordering of the versions might affect responses, I varied the sequence in which subjects responded to the versions. The five types of error are

misspellings, fragments, fused sentences, unnecessary quotation marks, and

word-ending errors (see Appendix A for a sample of one complete version; see

Appendix B for a list of all errors). Given my intent of offering a more complete

definition of what it means to be bothered by errors, I did not base my choice

of errors on any one criterion, though frequency was especially important.

Rather, I wanted subjects to consider a range of error types, so these errors

reflect various combinations of frequency, gravity, and form.

Seeking to avoid the unfamiliar or bizarre, I chose four categories appearing in Connors and Lunsford’s list of the twenty most frequent errors in

38

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

college students’ writing. However, these four hold various positions within

their list: misspellings (apparently the most common error at the time of

Connors and Lunsford’s study), word-ending errors (a combination of two categories Connors and Lunsford called “wrong/missing inflected endings” and

“wrong tense or verb form,” which were ranked Nos. 6 and 13), fragments

(ranked No. 12), and fused sentences (which the researchers collapsed with

run-on sentences near the bottom of the list at No. 18) (403). My fifth error—

unnecessary quotation marks—is an intentional outlier in that it did not appear even four times in Connors and Lunsford’s initial analysis of 300 papers

(as discussed later, I found this error received a distinct reaction not because it

was uncommon but because of certain implications associated with quotation marks).

Few studies have measured the relative gravity of errors made by native

speakers of English. Still, I chose errors that appear to reflect different levels of

severity. Surveys indicate nonacademics and academics deem fragments and

fused sentences to be especially bothersome (Hairston 797; Kantz and Yates;

Leonard and Gilsdorf 145; Long 6).1 Misspellings receive mixed reactions yet

often fall in a middle range. Two studies found that homophone errors, the

only misspellings the researchers examined, generally did not stand out one

way or the other (Leonard and Gilsdorf 146-47; Long 7). Two other surveys

found that certain homophone errors, such as “you’re” for “your,” were particularly bothersome; however, other misspellings, such as “recieve” for “receive,” were usually only mildly irritating (Hairston 801-06; Kantz and Yates).

Teachers in Wall and Hull’s study listed the three most serious errors found in

a sample text containing various errors, including misspellings, and only 1.4

percent of the responses referred to misspellings (276-77). Despite the time

and money spent on spell checkers, dictionaries, and spelling instruction, surveys therefore suggest that misspellings are usually only moderately bothersome, except with certain homophone errors or in job application documents

such as resumes (Monthei 39). Few handbooks give much attention to errors

involving word endings and, in particular, to unnecessary quotation marks,

indicating both are relatively innocuous.

Although an error can easily involve several aspects of language all the

way from phonology to semantics, the definition of an error usually hinges on

one particular linguistic feature. The five errors were accordingly selected to

reflect different linguistic features. Typically, misspellings are orthographic

matters concerning individual letters, while word-ending errors go a bit further by involving morphological omissions or misuses at the end of words. In

39

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

contrast, fragments and fused sentences involve entire phrases and clauses—

syntactic matters of creating and combining sentences. Unnecessary quotation marks are again a special category in that they deal most directly with

punctuation, rather than words or groups of words per se.

The purpose of including a breadth of error types was not only to represent more fully the spectrum of errors that exist but also to acknowledge the

possibility that reactions to error depend on error type. Within each of the five

categories, the four examples accordingly reflect additional differences. For

example, the misspellings consist of a homophone error (“they’re”), two misspellings so glaring they could be typographical (“aboutt” and “metods”), and

one misspelling many people might easily produce or overlook (“recomendations”).

The subjects typically completed all five versions in six to eight minutes.

At this point, I interviewed each business person for some forty-five minutes

using a semi-structured format (Merriam 73–74) to elicit reactions to a few

standard questions before probing subjects’ responses. These interviews form

the core of this study and focused on each subject’s reactions to errors from

the questionnaire, though the conversation would naturally broaden at times.

All questions were primarily designed to uncover the reasons why subjects did

or did not find the sample errors bothersome. Understanding why a person

reacts one way or another is difficult if not impossible to determine absolutely.

In particular, interviewees might simply say whatever they believe they are

expected to say, so I followed normal interview practices (e.g., Kvale 124–35)

to help create a relaxed atmosphere conducive to forthright, honest communication. The tone of the interviews was so relaxed that subjects themselves

did not strictly adhere to conventions of formal English, as excerpts presented

later reveal. To avoid encouraging subjects to distress over an error more than

they would normally, I limited my probing of any particular error to two questions (generally, requests for clarification). Nonetheless, the interview results

are artifacts of a discussion and cannot be taken as absolute proof of what

goes on in readers’ minds. Dialogues with individuals about their reactions

offer one means of exploring both the possibilities and probabilities behind

the numbers, but any self-reporting has its limits.

After the interviews were transcribed, I first analyzed each transcription

for its major themes and later considered how these might be refined and synthesized. Essentially, I read each transcription for dominant themes; larger categories of responses emerged when subjects’ reactions frequently overlapped.

This approach to analyzing transcripts reflects what Kvale refers to as “mean-

40

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

ing condensation” and “meaning categorization” in interview research (192;

also see Merriam 133–36).

Questionnaire results

The sample size is too small for statistical comparisons or large-scale generalizations about error gravity based on mean averages. However, it is important

to note certain levels of agreement and disagreement found in the questionnaire results, for these shed light on how a mean average can mask individual

differences within a population—differences with important ramifications for

preparing students to write in the business sector.

To illustrate this point, I wish to discuss first the overall averages. As seen

in Figure 2, fragments seem particularly bothersome among business people,

as Leonard and Gilsdorf (154), as well as Hairston (797), found. Not surprisingly, unnecessary quotation marks are least bothersome, while fused sentences

appear less bothersome than might be expected relative to misspellings and

word-ending errors. Nonetheless, all averages fall between the “somewhat bothersome” and “definitely bothersome” reactions.

An inherent problem with such averages is that, in condensing individuals’ variation into a single score to represent a population, averages are conducive to a monolithic perspective. A standard deviation can indicate variation,

but this single statistic can be difficult to appreciate. By considering individual

responses to particular errors, we can better understand the diversity with

which readers approach errors, for the raw scores make it clear that two types

of substantial variation exist: (1) among different readers’ reactions to a specific instance of error, and (2) among one reader’s reactions to errors of the

same type. Figure 3, for instance, reveals how each subject responded to misspellings. (Subjects in Figures

3-7 are arranged according to

Figure 2: Overall reactions to error types

highest to lowest averages,

3.00

with names alphabetized in Fragments:

2.70

cases of equal averages.) As Misspellings:

Word-Ending Errors:

2.59

seen within each vertical colFused Sentences:

2.48

umn, the first form of varia- Quotation Mark Errors:

2.30

tion is reflected in the range of

All Error Types:

2.61

reactions to any given error.

Every misspelling received KEY: 1

2

3

4

three of the four scores from Not bothersome Somewhat Definitely Extremely

at all

bothersome bothersome bothersome

the subjects, with the scope for

41

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

the first two errors extending from 1 to 4—a range supporting the argument

that error gravity depends on who is reading a text. For example, most subjects gave the homophone error “they’re” a “definitely bothersome” ranking,

but two deemed it “not bothersome” and three “extremely bothersome.” Only

one misspelling (“they’re”) received even a simple majority in terms of the most

common score it received.

The second form of variation can be seen by focusing on each horizontal

row. In Figure 3, some readers (e.g., Dee and Donna) were fairly consistent,

almost categorical, in how they reacted. A misspelling is a misspelling, it would

seem. Other readers, such as Eric, apparently evaluated each misspelling individually. He was the most bothered by the two misspellings that appear to be

typographical mistakes (he later explained this reaction was not based on

whether the misspellings were mere slips but whether they would “sound odd”

if read aloud). In such cases, error gravity does not simply depend on who is

reading, but what they are reading.

Figure 3: Reactions to misspellings

Dee

Betty

Eric

Jan

Nick

Susan

Donna

Lee

Martin

Daryn

Jean

John

Ralph

Charles

Error average

KEY:

recomendations

they’re/their

metods

aboutt

Subject

average

4

4

2

2

2

2

2

1

2

2

1

1

1

1

4

3

3

3

3

4

3

3

4

3

3

3

1

1

4

4

4

3

3

3

3

4

2

2

3

2

3

2

4

4

4

4

4

3

3

3

2

2

2

2

2

2

4.00

3.75

3.25

3.00

3.00

3.00

2.75

2.75

2.50

2.25

2.25

2.00

1.75

1.50

1.93

2.93

3.00

2.93

2.70

1

2

Not bothersome Somewhat

at all

bothersome

3

Definitely

bothersome

42

4

Extremely

bothersome

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

So can we safely say Eric and certain other readers will react to errors

based on the particular nature of each error? Indeed, Eric’s reactions to fused

sentences and unnecessary quotation marks continue to indicate that he considers each error separately rather than categorically, as seen in Figures 4 and

5. Figure 6, however, shows unusual consistency for Eric: Each word-ending

error was extremely bothersome to him. Three other subjects (Susan, Jan, and

Ralph) similarly show little variation in their scorings of word-ending errors,

despite having mixed reactions to misspellings. Such readers, then, appear to

defy generalizations—even when we generalize by claiming that these readers

themselves do not generalize and react instead to errors on a case-by-case basis. At the most, we can hedge by assuming these readers usually approach

each instance of an error on an individual basis.

To complicate matters, a few readers are much more consistent than Susan, Jan, or Ralph—a finding leading to generalizations requiring less hedging.

Figure 4: Reactions to fused sentences

Susan

Betty

Daryn

Dee

Jan

Eric

Martin

Donna

Jean

John

Lee

Charles

Nick

Ralph

Error average

Error 1

Error 2

Error 3

Error 4

Subject

average

4

3

3

3

3

3

1

2

3

3

2

3

2

2

4

3

3

2

3

2

3

2

2

1

2

2

1

1

4

4

3

4

3

1

2

2

2

1

1

1

1

1

4

4

4

4

3

4

3

2

1

3

3

1

3

2

4.00

3.50

3.25

3.25

3.00

2.50

2.25

2.00

2.00

2.00

2.00

1.75

1.75

1.50

2.64

2.21

2.14

2.93

2.48

Refer to Appendix B for the wording of each error.

KEY:

1

2

Not bothersome Somewhat

at all

bothersome

3

Definitely

bothersome

43

4

Extremely

bothersome

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

In Figures 3-7, the scores for Dee and Donna, for instance, show little variation

within a given error category, although Dee does vary her reactions to fused

sentences. Safe generalizations can also be made on the basis of other subjects’ responses to one error in particular, fragments (see Figure 7). True, each

fragment received three of the four scores, but it is the only category that never

received a “not bothersome” score from anyone—an additional indication that

fragments can be the most serious of errors. Perhaps the most notable pattern

with fragments, though, is within each individual’s responses: Nine subjects

gave the same score to each fragment (usually a 2 or 3), and only one subject

gave three different scores to fragments (Jean, who continued her pattern of

varying her responses within a category). Additionally, the average scores for

three of the fragments is the same (3.07), a surprising result considering these

averages derive from fourteen individuals whose other scores exhibit consid-

Figure 5: Reactions to unnecessary quotation marks

Jan

Susan

Dee

Eric

Donna

Jean

Lee

Betty

Charles

Nick

John

Daryn

Martin

Ralph

Error average

Error 1

Error 2

Error 3

Error 4

Subject

average

3

4

4

2

3

3

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

1

4

4

4

4

2

3

2

3

2

2

2

2

1

1

4

4

4

4

3

3

3

2

2

2

1

1

1

1

4

3

2

2

3

1

2

1

2

2

1

1

1

1

3.75

3.75

3.50

3.00

2.75

2.50

2.25

2.00

2.00

2.00

1.50

1.25

1.00

1.00

2.29

2.57

2.50

1.86

2.30

Refer to Appendix B for the wording of each error.

KEY:

1

2

Not bothersome Somewhat

at all

bothersome

3

Definitely

bothersome

44

4

Extremely

bothersome

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

erable variation. Fragments, then, seem especially likely to be treated in a categorical fashion.

Nonetheless, such clear patterns in the subjects’ reactions are rare. Each

subject’s average score for a category reveals yet another way to see the general

inconsistency despite an occasional tendency. Ralph and Charles are usually

among the least bothered by the errors, while Dee and—to a lesser degree—

Susan are likely to be among the most bothered. However, it is difficult to make

further generalizations about other subjects’ comparative tolerance. John, for

example, is among the most tolerant in terms of misspellings, fused sentences,

and misused quotation marks, yet he stands in the middle of the rankings for

word-ending errors and is among the most bothered by fragments. Compared

to other readers, Betty reacts in a clearly negative way to three errors, but other

reactions place her in an intermediate position with both fragments and unnecessary quotation marks.

Figure 6: Reactions to word-ending errors

Eric

Dee

Jan

Betty

Susan

Martin

John

Daryn

Donna

Lee

Nick

Jean

Ralph

Charles

Error average

Error 1

Error 2

Error 3

Error 4

Subject

average

4

4

3

3

3

3

2

3

2

3

2

1

1

1

4

4

4

3

3

3

4

2

2

1

3

3

2

1

4

4

4

4

4

2

3

2

2

2

2

2

1

1

4

3

4

3

3

4

2

3

2

2

1

1

1

1

4.00

3.75

3.75

3.25

3.25

3.00

2.75

2.50

2.00

2.00

2.00

1.75

1.25

1.00

2.50

2.79

2.64

2.43

2.59

Refer to Appendix B for the wording of each error.

KEY:

1

2

Not bothersome Somewhat

at all

bothersome

3

Definitely

bothersome

45

4

Extremely

bothersome

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

Despite a few tendencies that require qualifying, these numbers reveal

widespread inconsistencies—from type of error to type of error, from person

to person, and even among the responses of an individual person to errors of

the same kind. These quantitative results indicate how difficult it is to predict

the way a given reader, much less a group of readers, will react to errors, but

the interviews point to agreement in other ways—qualitative agreement.

Interview results

The interviews suggest that the inconsistencies and two forms of variation

discussed above are likely created by two broad categories of variables: textual

and extra-textual features of discourse. Before discussing particulars of the

interviews, I wish to summarize this finding, which is important in its own

right but also clarifies my focus for the remainder of this article.

Figure 7: Reactions to fragments

Susan

Eric

Dee

John

Jean

Betty

Daryn

Donna

Jan

Martin

Lee

Charles

Nick

Ralph

Error average

Error 1

Error 2

Error 3

Error 4

Subject

average

4

4

3

3

2

3

3

3

3

3

2

2

2

2

4

4

4

4

3

3

3

3

3

3

3

2

2

2

4

3

4

4

4

3

3

3

3

3

3

2

2

2

4

4

4

4

4

3

3

3

3

3

2

2

2

2

4.00

3.75

3.75

3.75

3.25

3.00

3.00

3.00

3.00

3.00

2.50

2.00

2.00

2.00

2.79

3.07

3.07

3.07

3.00

Refer to Appendix B for the wording of each error.

KEY:

1

2

Not bothersome Somewhat

at all

bothersome

3

Definitely

bothersome

46

4

Extremely

bothersome

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

First, the interviews indicate error gravity is easily mitigated or exacerbated by unique textual features that create or surround each instance of error—linguistic variables such as word choice, syntax, punctuation, or the

location of these variables within the text. Below are examples of how such

features seem to have led readers to give different evaluations to errors of the

same type:

• Lexical complexity (e.g., several subjects referred to this variable when

explaining why “aboutt” is more bothersome than “recommendations.”)

• Syntactic complexity (e.g., three subjects noted that an error within a

sophisticated sentence was especially bothersome because the sentence was difficult to understand even without the error.)

• Position within a paragraph (e.g., one subject said that a fused sentence

at the end of a paragraph was not bothersome because the meaning of

the paragraph was clear by this point in the passage.)

Second, error gravity is affected by extra-textual features that more directly go

beyond the language of a text.2 These include aspects of the communication

situation, such as whether a document is a formal letter from an executive or a

sticky-note to a colleague. Extra-textual features also include the reader’s interpretative framework—the way in which each reader encounters the text

having unique experiences and expectations that affect his or her interpretation of errors, as Williams and Lees have argued. Perhaps readers judge the

same error differently because the uniqueness of each person’s life has formed

a singular set of assumptions, memories, and preferences—some of which are

relevant to the reading of errors. Indeed, the interviews suggest that extratextual features produce even more variation than a standardized questionnaire can uncover. For example, any given pair of readers who scored the same

error as “extremely bothersome” still reacted differently in terms of what it

meant for each of them to be so bothered, a difference that the questionnaire

alone could not indicate.

Although textual aspects of error are important, it is especially crucial to

understand extra-textual features. Too many students, if not teachers, view

errors simply in terms of “breaking rules”—a failure to adhere to textbook dictums for producing a text. By considering how forces beyond the text shape

the reader’s reactions and by considering how errors in turn shape the writer’s

ethos perhaps students can better understand that writing means more than

the production of texts, more than adhering to abstract guidelines removed

47

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

from the needs, biases, and intentions of readers. The remainder of this article, therefore, will elaborate on extra-textual issues. In particular, I concentrate on what the interviews illuminate the most: the ways in which readers

apparently use errors to construct the writer’s ethos within the context of the

business community.

To clarify this notion, I must first identify the most pervasive theme found

in the interviews, what I call the “meaning/image” theme. This theme is the

bottom line as to why errors bother readers: Errors create misunderstandings

of the text’s meaning, and they harm the image of the writer (and possibly the

organization to which the writer belongs). Image, as I will explain shortly, involves several extra-textual issues, but I want to stress that all subjects drew

on both ways of reacting to an error, indicating the extent to which these concepts—textual meaning and the writer’s image—are fundamental to any definition of error gravity. Each subject noted that some errors were definitely

confusing (especially the syntactic errors) or, more commonly, momentarily

interrupted the flow of reading enough to slow communication. Charles said

of one fragment: “It slows me down and confuses me; I have to go back and do

it again, and then I have to say, ‘What are they really trying to tell me?’” As

noted earlier, some readers consider these meaning-hampering errors to be

the most serious, perhaps the only ones worthy of much concern.

But the interviews indicate such errors are not the only types leading to

negative reactions. The subjects frequently accounted for even the most negative scores not by discussing their confusion

The interviews suggest . . . that the extent to as readers, but by commenting on the imwhich errors harm the writer’s image is more age the error creates of the writer. Even

serious and far-reaching than many students though the questionnaire consisted of five

and teachers might realize. versions of the same document, making it

easier for readers to interpret the meaning

of the document, concerns about the writer’s image arose so often and emphatically that it clearly seems a determinant of error gravity for these subjects.

The interviews suggest, in fact, that the extent to which errors harm the

writer’s image is more serious and far-reaching than many students and teachers might realize. At times, the subjects stated in very general terms that errors affect a person’s credibility as a writer or employee. More often, though,

the subjects noted specific image problems, which I have synthesized into three

major categories and eleven subcategories. These interrelated categories focus on extra-textual features of communication, but in varying degrees, mov-

48

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

ing from the writing skills of one person, to concerns about that person beyond his or her writing skills, to global issues affecting the organization and

others. (My order of presenting the three categories reflects this movement;

within each category, though, the subcategories are discussed in an order that

merely facilitates comparisons and contrasts.)

On one level, these categories add yet more inconsistency, for readers discussing the same error often formed different images of the writer. Although I

will note a few exceptions, a particular image problem was usually not associated with just one category of error, again suggesting difficulties in predicting

responses to error. On another level, however, the following images occurred

so frequently throughout the interviews that I believe these categories reveal

consequential qualitative similarities among business people’s reactions to

error, implying similar ways of making meaning through reading errors and

through reading much more than we might suspect into these errors. Space

limitations prohibit me from exploring these images fully, but I believe the

following offers a more complete understanding of what it means for a writer’s

credibility to be jeopardized by errors.

Category 1: writer as a writer

The first major category is based on the writer’s credibility as a writer—not a

professional writer, but someone whose job includes some writing. This overall image problem arose frequently and with all errors. It contains four subcategories, the first three of which are especially interrelated.

Writer’s image as a writer

1.1 Hasty writer

1.2 Careless writer

1.3 Uncaring writer

1.4 Uninformed writer

1.1: Hasty writer

First, errors can create the image of someone who writes too hastily. This theme

was one of the most common, as each subject at some point spoke about the

errors in terms of time demands or the lack of time the writer gave the sample

document. Usually, the subject indicated the writer was hasty as a whole in

writing the document, did not take time to proofread in particular, or rushed

to meet a deadline. The subjects were often sympathetic to the time demands

49

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

faced by an employee; several noted how they themselves make mistakes in

the rush to accomplish extra work in an environment of fierce competition or

stressful downsizing. Despite this compassion, most subjects reacted negatively. That is, a subject might appear both understanding (“I know how rushed

people are”) and disapproving (“These errors still bother me even though I

sympathize”). Indeed, a few subjects indicated that having to rewrite or reread

error-filled documents cost them valuable time of their own, making them

less likely to be forgiving. While subjects occasionally tempered their negative

reactions by acknowledging that errors often result from huge demands on an

employee’s time, these errors also suggested the writer lacks the ability to handle

these incessant demands on business people who must write as part of their job.

1.2: Careless writer

A closely related subcategory is the image of a careless writer, one who is inattentive or neglectful when writing. This image was also one of the most common throughout the interviews. Subjects often used the terms “careless” and

“hasty” jointly, but the former was more negative and frequent, in addition to

implying the error did not result from a lack of time. Raising his voice and

gritting his teeth, John said: “This stuff really bothers me! It’s not so much even

that you are in a hurry but that you are extremely careless to do these kinds of

sentences.” Betty discussed how she refused the services of certain student

interns whose errors indicated to her that they

At times, the subjects moved beyond the would not proofread carefully. Errors eliciting

writer’s caring about the document the “careless writer” image clearly bothered subitself; they often stated that the writer jects, for these mistakes indicated the writer has

did not care about the reader or what- the ability to avoid errors but did not focus on

ever exigency prompted the document. doing so. Indeed, subjects such as Dee frequently

used the harsher terms “lazy” and “sloppy”: “I

guess it’s lazy—all you have to do is click that button to run spell check.”

When making such comments, subjects generally did not assume the employee to be careless in all duties, just in terms of writing or writing one particular document. As will be noted shortly, other comments indicate there are

times when errors do suggest more widespread carelessness (see subcategory

2.2).

1.3: Uncaring writer

At times, the subjects moved beyond the writer’s caring about the document

itself; they often stated that the writer did not care about the reader or what-

50

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

ever exigency prompted the document. The major difference between this third

subcategory and the previous two is the extent to which the reader personalized a mistake, blaming it neither on time nor a careless habit as much as on

an inappropriate attitude toward something or somebody. Though this subcategory was the least frequent within category 1, the ramifications of being

uncaring can be just as serious in business discourse as in academic writing,

perhaps more so. For example, Lee said, “If this was something important that

they wanted me to read . . . and had a lot of these little sloppy errors, then that

would probably affect the way I thought about that person and how important

that proposal was to them as well.” Charles said that any sort of error on application materials in particular could elicit this image: “What they say is that if a

person doesn’t care more about themselves than to not present themselves in

the best possible light, how in the world can you expect them to care about you

and your business?” In such ways, errors can evoke the image of a writer who is

not merely careless but detached, disrespectful, or even unmotivated.

1.4: Uninformed writer

So far, I have discussed three subcategories of image problems dealing with a

person’s writing ability, and each concentrates on errors perceived as accidents—as problems resulting not from a writer’s failure to understand certain

conventions, but from haste, carelessness, typographical mistakes, or apathy.

With this next theme, however, errors suggest an uninformed writer, one who

lacks relevant knowledge (almost always, a knowledge of conventions for formal English).3 Taking three forms, this fourth subcategory was particularly

widespread. First, some subjects assumed the writer lacks knowledge about

one error or type of error. Lee, for instance, suggested that the person who

wrote “they’re” instead of “their” is simply unaware of the difference between

the two. Other times, interviewees assumed that the writer lacks a larger understanding of usage, spelling, or punctuation. After discussing fused sentences,

Susan concluded: “Possibly, the writer just does not understand how to deal

with punctuation.” Finally, on rare occasions this image of an “unknowing

writer” referred to the knowledge of the topic of the document. Jan, for example, said that the sample errors made her question whether the writer understands the material being covered; for Jan, the errors indicated that the writer

struggled with language for something to say, as a result of not really comprehending the issue under discussion.

As a group, the subjects alluded to each source of error—accidents versus insufficient knowledge—at roughly an equal rate, but they did not clearly

51

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

agree on which errors were associated with which source. As noted, I chose

the misspellings “metods” and “aboutt” because they seem to be typographical

Error gravity is not necessarily determined by mistakes, and almost all subjects gave this

explanation. However, there was no such

whether an error is perceived as an accident

pattern of agreement with other errors.

rather than a knowledge problem.

One might well wonder if readers treat

knowledge-based errors more severely since these stem from what some people

view as ignorance (indeed, some subjects phrased the problem this way). Long’s

study of academics’ reactions led him to conclude that errors of carelessness

are more tolerable (10), but while some of my subjects were lenient with what

they deemed accidents, others viewed these as more bothersome because the

writer, in these readers’ estimation, essentially decided to ignore a problem

that could have been easily fixed. Thus, error gravity is not necessarily determined by whether an error is perceived as an accident rather than a knowledge problem.

Category 2: writer as a business person

All subjects indicated errors can harm one’s image by reflecting not just writing ability but other traits, skills, or attitudes important for someone in business. This second category has five subcategories.

Writer’s image as a business person

2.1 Faulty thinker

2.2 Not a detail person

2.3 Poor oral communicator

2.4 Poorly educated person

2.5 Sarcastic, pretentious, aggressive writer

2.1: Faulty thinker

The most commonly mentioned of these five subcategories involves what could

be called a “thinking problem.” Several subjects speculated or firmly asserted

that a given error resulted from faulty thinking abilities—not a deficient knowledge of language (see subcategory 1.4), but limited reasoning skills. This image developed almost exclusively with errors connected more with syntax

(fragments and fused sentences) than with individual words or punctuation

(misspellings, quotation mark errors, word-ending errors). When explaining

possible causes of a fused sentence, Susan stated: “Well, again, I think it shows

52

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

a lack of ability to understand what a complete thought is. . . . So I guess I

would be very fearful if this were in an application.” Ralph believed the sample

fragments were likely caused by “not having complete thoughts.” Readers did

not associate syntactic errors with only this one image. Daryn, in fact, associated the author of the fused sentences with four problems: “They lacked some

basic writing skills or education, and they didn’t think very logically, and they

didn’t proofread it.”

While I want to avoid “correcting” the subjects’ personal reactions, it is

highly questionable that the sample fused sentences and fragments represent

incomplete thoughts in the context of the document in which they appeared.

Possibly, the occasional use of the term “complete thought” was influenced by

teachers and traditional handbooks that define a complete sentence as a complete thought, but other language choices suggest subjects perceived, correctly

or not, a poor or incomplete reasoning process. Ralph, for example, went on to

say that the faulty sentences reminded him of someone struggling to think

through an issue: “Most of the time on a rewrite, when you go back and formulate what you are trying to say, you can always put it in a better and more

complete thought structure. But this, this was not thought out well.” Still, the

use of “complete thought” is one indication that subjects’ reactions to error

might not be accurate or fair—an observation I will return to later.

2.2: Not a detail person

Similarly, some subjects saw errors as indicative of someone who struggles

with details, but this image problem was not limited to syntactic errors. Some

subjects assumed that writers who do not notice the accidental errors discussed earlier might overlook other (and often more important) details connected with their job. This concern did not arise frequently, but interviewees

involved in banking and investment, despite their different job duties, were

especially alarmed when they perceived the writer could not handle details.

Daryn, a vice-president with a brokerage firm, said:

There is a lot of written communication that goes out to our clients, and we want

it to be as accurate as possible. It’s somewhat bothersome because if someone

makes an error in writing a word, are they going to make an error in typing a

number? In our business, we work with money, and a small error with a digit can

make a big difference to a client.

Only one other image problem (subcategory 3.2) is so clearly linked to the particular nature of certain professions. As noted earlier, finance was best represented among the subjects (four bankers and one investment broker).

53

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

Additional research might be needed to determine if people in other professions are especially sensitive to particular errors.4

2.3: Poor oral communicator

This theme was associated with various errors from the questionnaire, even

though only the word-ending errors would normally be considered problems

in speech (a fact none of the subjects noted). This image problem was the least

mentioned of all found in this study, yet a few subjects were concerned that

the writer who commits errors in writing might commit many errors in speech

as well. Subjects generally did not posit a cause/effect relationship between

errors in speech and those in writing; they simply noted the patterns of error

would likely be reflected in the writer’s speech. A few subjects even assumed

the errors hint at more than just problems with usage and grammar in

speech. Betty, the human resources administrator, feared that the writer would

struggle with the important negotiation and conflict-resolution skills needed

in day-to-day discussions.

2.4: Poorly educated person

With the next image problem, subjects cast doubts on the writer’s education,

usually in terms of writing instruction but sometimes a more general doubt

about the writer’s overall education. In general, this concern was related to a

knowledge problem, primarily in terms

Subjects indicated that the educational of having learned appropriate linguistic

shortcoming seems to have involved more than forms (see subcategory 1.4). Other times,

merely a failure to acquire knowledge. though, subjects indicated that the educational shortcoming seems to have involved more than merely a failure to acquire knowledge—such as failing to

care about one’s work in school or not having been taught to proofread carefully.

Whether the “blame” was placed on the writer as a student or on the

educational system, the majority of subjects at some point connected errors

with the lack of a successful education (for no clear reason, male subjects from

Mobile were unlikely to offer or emphasize this image problem). Most subjects, possibly out of concern they might somehow offend me, indicated the

problem was with the writer’s inability to learn, not ineffectual teaching. Usually, they assumed the writer as a student failed to acquire the knowledge of

grammar and the English language that, they believed, would have prevented

many errors. A few subjects seemed to blame the educational system, espe-

54

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

cially public education (again, perhaps because of the interview situation).

Martin referred to the errors in the sample document by seeming to critique

all educational levels as well as the newly graduated professional:

Those are glaring—that’s junior high. Why do so many kids get out of school without a minimum level of skills? When I got out of high school, they tested you. . . .

I fail to see how people can graduate with a four-year degree in electrical engineering with something like this.

2.5: Sarcastic, pretentious, aggressive writer

This theme might initially seem odd, for it concerns the image of the writer as

sarcastic, pretentious, or aggressive. Most subjects offered comments falling

into this subcategory but did so only with one

error: unnecessary quotation marks. Al- One error, unfortunately, can contribute

though a few subjects saw some of these as to diverse problems as well as to problems

inappropriate strategies for emphasizing associated with just that error.

words, comments such as Betty’s were common: “I rated that a 3 because I felt like there was some sarcasm in making fun

of somebody at their expense. . . . I am in judgment of the writer because the

writer is in judgment of this party they’re referring to.” Jean went further by

suggesting that the writer “is probably aggressive, probably likes to be noticed.”

Ralph stated that the image was so distracting that it hampered communication, indicating how these two issues (image and meaning) are not necessarily

disconnected: “That’s pretentious to me. What is your intent by putting unnecessary quotation marks? Why did you do that? This is just throwing up a

roadblock. It’s keeping me from reading this clearly.”

As noted, a particular image problem was rarely associated with only one

type of error. Subcategory 2.1 is an exception, and the quotation mark errors

are another. These exceptions illustrate an additional layer of complexity: An

error can contribute not only to the broader image problems noted previously

(and subsequently), but also to distinctive image problems associated primarily—or exclusively—with that error. Unnecessary quotation marks might, for

example, foster the image of a hasty reader who did not take time to ensure

judicious use of punctuation (subcategory 1.1); other mistakes might contribute to this same image. But the same readers might see these quotation marks

errors as also creating a “tailored” image problem, one fitting just this type of

error. One error, unfortunately, can contribute to diverse problems as well as

to problems associated with just that error.

55

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

Category 3: writer as a representative

Up to this point in my taxonomy, the ethos problems have been principally

associated with possible causes of errors (such as carelessness or inappropriate attitudes) and have focused on images of only the writer. With the final

major category, the image problems grow out of the effects of errors on a group

of people. Just as errors reflect on the individual, the individual reflects on the

organization. This category did not appear as often as the first two, but subjects were emphatic when these concerns arose, as demonstrated by their gestures and the length at which several would elaborate (one subject even asked

me to stop recording for several minutes while he explained the embarrassment for the company because of usage errors produced by one high-placed

executive).

Certainly, all image problems falling into the other two major categories

can affect the credibility of an organization. However, subjects often did not

settle for merely implying that errors harm the company’s image; they explicitly stated that they saw the writer as a poor representative of the company.

Many times, subjects did so by making a general observation. Jan, for example,

told me, “Errors tell what your company’s like.” Just as often, subjects focused

on two specific ways in which errors evoke the image of a representative who

can be an organizational liability.

Writer’s image as organizational representative

3.1 Representing the company to customers

3.2 Representing the company in court

3.1: Representing the company to customers

First and most obviously, the writer can represent the company in ways that

harm customer relations and sales. In particular, the writer might cost the organization customers by representing it as unprofessional, ineffective, or in

terms of any of the problems falling under categories 1 and 2. For instance,

Daryn said that clients might not want to do business with a brokerage firm

whose employee sends a “sloppy” letter containing errors, and Jan went beyond her general comment noted above:

The banking industry is more or less thought of as being a perfect industry. . . .

And we try to do everything right, and I guess it bothers me if we present something on a piece of paper that is not . . . as near perfect as it can be. If I’m going to

write you a letter, then my image went out in that letter, or my company’s image.

56

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

My bank’s image needs to be as nearly perfect, and a grammatical error, I think,

would be offensive to some of my customers.

3.2: Representing the company in court

This theme might be less obvious to teachers and students, for litigation is not

yet a frequent concern in most classrooms. For several subjects, the errors indicated the writer would not be an

asset as a representative of the Readers in business not only draw on their own

company in legal disputes. This individual ways of interpreting a text, but also make

concern was brought up only by guesses as to how other people inside and outside the

subjects in professions frequently organization might be bothered by errors.

involving contracts or litigation—

real estate, insurance, health care, and (to a lesser extent) banking. Frequency,

though, can belie the importance of some issues. These subjects were usually

emphatic in discussing this problem. Jean commented:

And how is the company going to be represented when this is presented as evidence to a legal forum? Because the worst thing that can happen is for the opposing attorney to turn around and say that this person cannot write, cannot spell,

has atrocious grammar. How can they have the education and knowledge to supervise that person?

Even Charles, whose survey results suggested he was among the least agitated

by errors, was emphatic about how the writer might represent the company in

court.

You go into court, okay? Whatever your writing is, they blow it up [onto a screen]

the size of a wall! [He waves his arms.] The opposing attorney goes through whatever you have up there word by word. And if it doesn’t look good to a jury or to

anybody else, and if you have anything up there that’s not right. . . . they’re going

to use that against you. Opposing attorneys try everything in the world to make

you look bad!

When making comments about the writer as a representative, subjects were

primarily concerned about how other people might react to errors; on a few

occasions, subjects would state, in fact, that they might not make certain judgments, but they knew other people would. This guesswork might partly account for the diverse reactions subjects often had to the same errors. Readers

in business not only draw on their own individual ways of interpreting a text,

but also make guesses as to how other people inside and outside the organization might be bothered by errors. As seen throughout this study, a reader re-

57

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

acts to errors not merely by comparing the text to linguistic rules or conventions—a relatively simple act that only seems to constitute the process of responding to errors. A reader reacts as well by considering extra-textual issues,

such as making assumptions about how, in a courtroom, other people (such as

lawyers) might exploit errors while portraying the company to yet another set

of people (such as a judge and jury). Such extra-textual entanglements are

rarely as rich in students’ academic writing, a condition that might partly account for the traditional focus in the classroom on only the textual aspects of

error.

Implications for teaching

This study drew on a small population to describe the interpretative processes

of business people and how they arrive at error gravity—not to create a hierarchy of error gravity or to quantify reactions. Looking beyond mean averages,

we see subjects offering a surprising range

We should not imply that errors that seem of evaluations, often by considering each

minor to some people (e.g., to the writer or the error individually rather than generically.

teacher) are not worth much attention. Because of this range, I suggest teachers

send a prudent message about error gravity. On average, some types of errors might appear egregious and serious, with

others seeming minor. The key word, however, is “average”—an abstraction

that emphasizes commonalty and minimizes disparateness. It is equally important for students to appreciate that some readers can deviate greatly from

the norm, and we should not imply that errors that seem minor to some people

(e.g., to the writer or the teacher) are not worth much attention. Kantz and

Yates found that teachers across the college campus can also have notable disagreements about specific errors despite some larger patterns of agreement,

so students must realize that these tensions—general hierarchies of error disrupted by specific instances of disagreement—are not limited to just one communication context.

The interviews shed light on the negative effects of error and why we cannot assume the only serious errors are those hampering communication of

textual content. Although errors can impede meaning, a more complex and

equally important problem is how readers use errors to construct a negative

image of a writer or organization. Again, students must realize the variation

among readers’ responses. For some readers, simple accidents or certain errors have little impact, while other readers see the same errors and create a

damning portrait of the writer. Despite this variation with individual errors,

58

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

this study has uncovered categories of problems that better define “negative

image” and what it means to be bothered by errors. Students—if not teachers—who perceive errors as unimportant might consider these themes in order to appreciate the impact of errors on nonacademic readers. By

understanding the myriad ways in which a writer’s ethos can be unnecessarily

endangered by errors, many students

should be better motivated to avoid mis- By understanding the myriad ways in which

takes that careful proofreading would pre- a writer’s ethos can be unnecessarily

vent. Indeed, Haswell found in one analysis endangered by errors, many students should

that the clear majority of his students’ er- be better motivated to avoid mistakes that

rors were essentially proofreading mistakes careful proofreading would prevent.

they could easily correct (601).

Some students perceive errors to be minor concerns and teachers who

think otherwise to be “picky” (i.e., inconsequential). In some ways, these students are right. As a composition teacher, I might be annoyed or momentarily

confused by errors, but if it were not for the vital fact that I could decide to

lower the student’s grade, the way in which I personally react to errors might

not really matter. In the nonacademic workforce, errors can affect people and

events in larger ways. Most subjects recounted occasions when errors had detrimental consequences—an indication to me that errors truly bothered them

and that their negative responses were authentic. I refer to more than loss of

revenue for a company. Errors in some contexts can even be health hazards.

Jean, a health-care administrator, described an incident in which a patient was

given twice the normal dosage of a complex medication because of written

instructions containing a misplaced modifier and garbled syntax. This situation is not typical, but one implication of this study is that students should

beware of basing language choices on the “typical” reaction of readers. Instead,

students should understand the diverse ways errors can affect a particular

reader in a given situation.

While it is tempting to end on that note, I cannot in good conscience do

so. At the risk of complicating the implications of this study, I have two final

caveats.

First, we should be uncomfortable with any “easy out” for paying stricter

attention to grammar and usage, for this mindset could lead teachers and students alike to obsess over one aspect of writing while giving less attention to

other significant concerns. Indeed, practically all subjects commented on the

importance of matters such as logic, organization, and conciseness—even

though my questions centered on mechanics. Lee summed up his attitude to-

59

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

ward errors this way: “I would just go ahead and get to the point rather than

dwell on the errors.” This study focuses on defining the components of negative reactions to error, and most errors in the questionnaire did appear bothersome to a degree, even for Lee. Still, I do not wish to imply the subjects were

so intolerant that students should worry that one slip in language will lead

business people to make all of the judgments

Error avoidance, I submit, should have a covered in this study. A person’s ethos is espresence in the composition curriculum— tablished by a network of extra-textual and

but without overpowering it. textual features, error being but one. In a previous study, in fact, I found various categories

of positive images that are especially appropriate in business and created

through certain textual features of business communication (Beason). Whether

we believe it to be the optimum situation or not, errors have an impact on the

writer’s image and communicability. Error avoidance, I submit, should have a

presence in the composition curriculum—but without overpowering it.

Second, we should also be uncomfortable with stressing any aspect of

writing based on what might be inaccurate generalizations, which I believe

are too much with us already. Despite the work of Shaughnessy and others,

some teachers still make erroneous generalizations about students’ linguistic

aptitude based on dialect-based “errors” that in truth reflect valid grammatical systems, and I do not wish to support these or other unjustifiable judgments made within and outside our profession. Teachers should not ignore

one finding of this study: Errors are conducive to a business person’s making

judgments about the writer’s credibility and capabilities. Yet if we as teachers

stress error avoidance simply because of this fact, are we giving credence to

stereotypes? A few subjects themselves realized their generalizations about,

say, a writer’s thinking ability might be unfair. Susan, one of the harsher readers, said: “A lot of my stereotypes about people who make those kinds of errors

have proved unfounded.” Such subjects were honest enough to qualify their

judgments, yet they were still willing to offer more generalizations.

We should, then, help students understand the depth and significance of

this all-too-human response to errors. While discussing negative images created by errors, teachers should not sanctify the ways in which people make

hasty generalizations about writers’ unconventional language choices. In helping students avoid errors, we help them avoid being victims of such generalizations. But in offering this assistance, we should also teach this next generation

of professionals that errors in formal writing do not necessarily reflect a person’s

overall personality, demeanor, or competence.

60

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR

Appendix A: Sample questionnaire

(Fragments)

Definition: A fragment occurs when the writer punctuates a group of words so that it

appears to be a complete sentence, when in fact it cannot stand alone as a complete

sentence.

This report presents the results and recommendations of the task force.

Which was appointed to study the most efficient method of storing all

shipments of purchased materials. After evaluating four methods, the

task force recommends the Stacker method as the most feasible.

______

Two years ago, a similar study was done by members of the accounting

department. However, their study was negated. Because it was based on

outdated estimates of the costs involved.

______

We examined four storage methods most frequently used in our industry:

(1) Trax, (2) Stacker, (3) Wide-Aisle Racking, and (4) Floor Storage. These

methods were evaluated according to the following criteria. Space

requirements, initial investment costs, and yearly operating costs.

______

The attached table summarizes the data gathered about the four methods.

The company comptroller supplied us with estimates of prices. The

following section is a brief description of the pros and cons of each of the

four options. Based on the criteria listed above.

______

In the spaces provided, use this scale to indicate how bothersome you find each error.

KEY:

1

2

Not bothersome Somewhat

at all

bothersome

3

Definitely

bothersome

4

Extremely

bothersome

Appendix B: Errors embedded in questionnaires

Misspellings

1.

2.

3.

4.

recomendations

they’re (for their)

metods

aboutt

Fragments (see Appendix A also)

1. Which was appointed to study the most efficient method of storing all shipments

of purchased materials.

2. Because it was based on outdated estimates of the costs involved.

3. Space requirements, initial investment costs, and yearly operating costs.

4. Based on the criteria listed above.

61

CCC 53:1 / SEPTEMBER 2001

Fused sentences

1. The task force evaluated four methods the task force recommends the Stacker

method as the most feasible.

2. Two years ago, a similar study was done by members of the accounting department however their study was negated because it was based on outdated estimates

of the costs involved.

3. We examined four storage methods they are the most frequently used in our industry: (1) Trax, (2) Stacker, (3) Wide-Aisle Racking, and (4) Floor Storage.

4. The attached table summarizes the data gathered about the four methods the company comptroller supplied us with estimates of prices.

Unnecessary quotation marks

1. After “evaluating” four methods, the task force recommends the Stacker method

as the most feasible.

2. However, “their” study was negated because it was based on outdated estimates of

the costs involved.

3. These methods were evaluated according to the following criteria: “space” requirements, initial investment costs, and yearly operating costs.

4. The following section is a brief description of the “pros and cons” of each of the

four options based on the criteria listed above.

Word-ending errors

1. Six years ago, the company had chose to adapt this method but then decided otherwise.

2. Two years ago, a similar study was suppose to have been done by members of the

accounting department.

3. These methods were evaluated according to the following criteria: space requirements, initial investment costs, and year operating costs.

4. In our analysis, we believe we have treated each option fair and concluded that the

Stacker method is the best.

Notes

1. These studies use the term “run-on sentence” to refer to two independent clauses

having neither punctuation nor a coordinating conjunction separating them. I use

the other common term used to refer to this error (“fused sentence”) because teachers and textbooks sometimes use “run-on sentence” to refer to other mechanical

or even stylistic problems.

2. Although subjects discussed textual features such as those identified here, I am

not suggesting there is no overlap between textual and extra-textual aspects of

discourse. Some subjects themselves indicated that textual features such as word

length are not necessarily a factor in error gravity for all readers or in all situations.

62

BEASON / ETHOS AND ERROR