Active Reading & Critical Thinking: College Writing Guide

advertisement

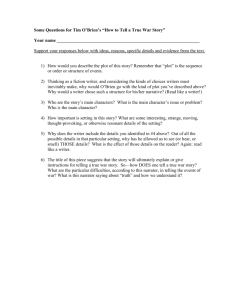

Adapted from 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology by Samuel Cohen Introduction for Students: Active Reading, Critical Thinking, and the Writing Process Reading and Writing Hard work, preparation, and lots of reading can add up to good writing. We become active, critical, intelligent readers and writers by carefully reading the writing that others have done and then applying what we have learned to our own writing. Reading and writing are most of what you will do in your college courses. The strongest readers and writers have learned to see these activities as inextricably intertwined. You read, you write, then you read some more, then you write again. And this pattern applies in nearly all of your classes, not just those in English and history. The best thing you can do with the texts you encounter in school and in the world is try both to understand them and to evaluate them, and be open to having your mind changed by them. Active Reading We read for a number of reasons. We want the news, we want information, we want to be entertained. We want to hear other people thinking. We want to be taken out of ourselves and live other lives. We also read because it is crucial to learning how to write. To write well – to express your ideas efficiently and clearly – you need to observe how others do it. Working with ideas – handling the ideas of others and presenting your own – is the most important thing writers do, and so the most important thing for writers to learn. Since it is so important, of course, it is difficult. Like if like that. The goal is for you to eventually be able to engage with ideas, hold them up to the light, turn them this way and that, and maybe modify them in some way, add something, take something away, take them apart entirely, and offer your own instead. Your job when reading literature or news articles is not to take what the text says as the gospel truth. Instead, you should evaluate what you read. This doesn’t mean you should treat literature as movie critics treat movies: your task is not to simply give a thumbs up or down. Ask questions of the text, argue with assumptions being made, examine how ideas are connected, and test these connections. Your job when reading literature or news articles is to read actively rather than passively. Think of passive reading as like watching television. Most people watch television while doing something else completely. Active reading, in contrast, requires full attention. Your mind needs to be sitting up, concentrating on the page, ready to reach down into the page and grab the words. Adapted from 50 Essays: A Portable Anthology by Samuel Cohen Ways to Read Actively Read consciously. In addition to being awake, it is important to be conscious of the situation you are in. Why are you reading? Merely for comprehension, or for argument about the ideas? Read critically. Always ask yourself what you think about the writer’s arguments or how their literary techniques communicate ideas and feelings. Read with a pencil in hand. Often, the writer is talking to you, and you are free to answer back. Many students leave their books untouched, thinking that they will remember what they read. Annotating is the surest way to read actively. Obviously, do NOT write in your textbook. If you purchase any of the novels that we will read you should annotate while reading. Many readers like to take notes in a notebook or computer. You can copy important quotes, you can paraphrase ideas, you can summarize, and you can note your reactions as you read. Doing these things can make you think about what you’re reading. Critical Thinking and Critical Reading Critical thinking doesn’t mean being critical in the everyday sense, that is, being negative. It means being inquisitive, evaluative, even skeptical. When reading, it means thinking not just about what someone says but about the unspoken assumptions that lay behind what they say, the unnamed implications of what they say, and the way they say it. It also means evaluating – asking if you agree with a writer’s implicit and explicit conclusions, even asking if you agree with the framing of the question asked. Critical thinking is an all-encompassing term for a number of activities that add up to active, thoughtful engagement with a subject. It enables people to actively judge and process the things they read and hear rather than passively accept them. It enables individuals to accept or reject the common wisdom that is all around them, in everyday life, at school or work, and in politics. When applied to reading, critical thinking might be called “critical reading.” Annotating/Note-taking: Identify the main topics, secondary topics, main points, supporting points, examples and evidence, ideas you agree with, ideas you disagree with, ideas you want to think more about later, references or words with which you are not familiar. Critical Reading: What is the writing situation? What is the writer’s subject? What is the writer’s main point and what is the purpose in making that point? What assumptions does the writer make? What further conclusions can be drawn from the writer’s argument?