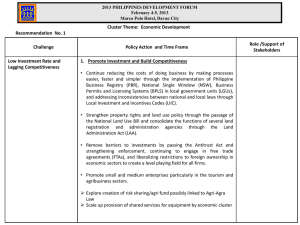

resolving conflict in muslim mindanao

advertisement