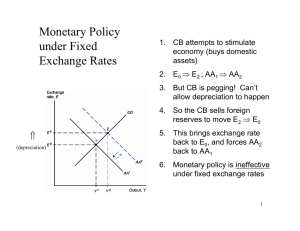

Dollarization and Monetary Unions

advertisement