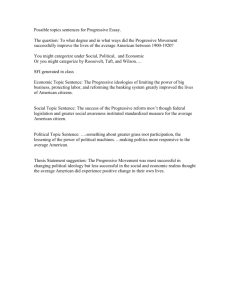

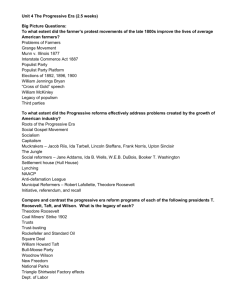

Introduction: The Progressive Impulse in Education Bertram C

advertisement