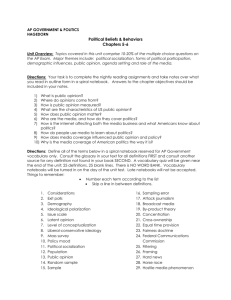

CHAPTER 1 What is Politics?

advertisement