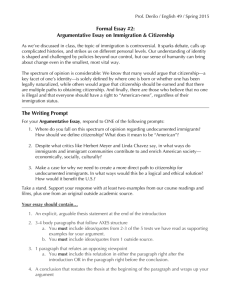

Scott Titshaw The growing use of assisted reproductive technology

advertisement