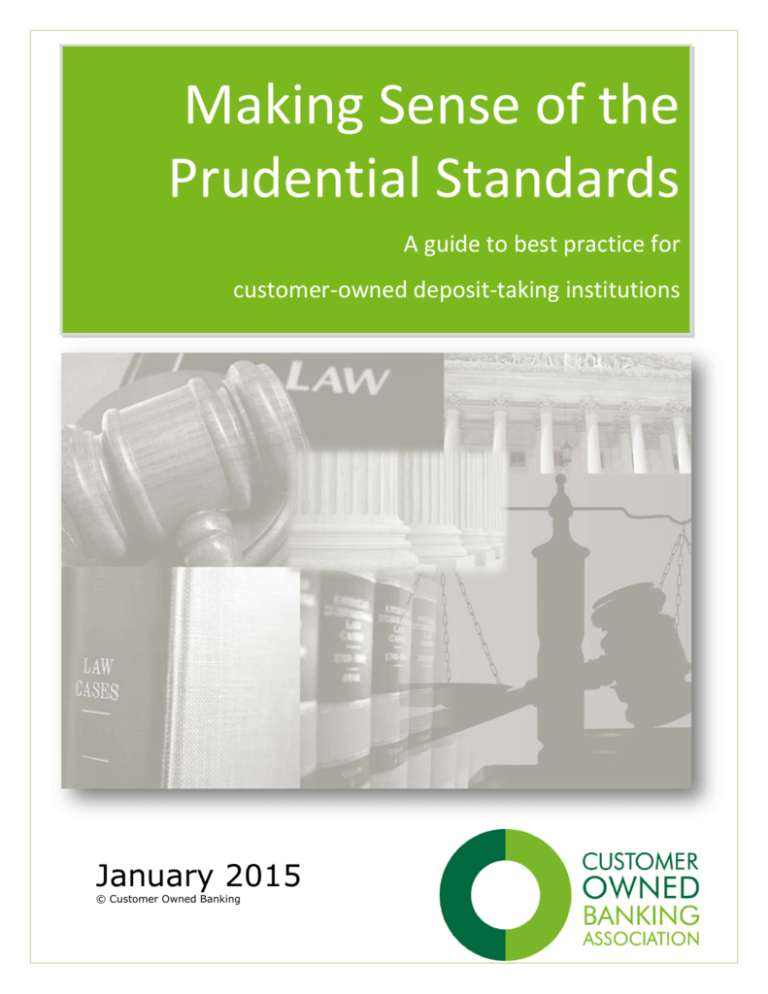

And 2015

Making Sense of the

Prudential Standards

A guide to best practice for

customer-owned deposit-taking institutions

January 2015

© Customer Owned Banking

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

STATEMENT AS TO THE CURRENCY OF LAW

This Guide refers to the APRA Prudential Standards and Guides as at 1 January

2015.

IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER

All care was taken in the preparation of this Guide. However, this Guide is not to

be used or relied upon as a substitute for professional legal, accounting or risk

management advice on a particular matter.

Customer Owned Banking Association, its directors and officers, and the authors,

expressly disclaim all liability to any person in respect of this Guide, and any

consequence arising from its use by any person in reliance on the whole or any

part of this Guide.

This disclaimer does not exclude any warranties implied by law that may not be

lawfully excluded.

VERSIONS

First published February 2010

Updated December 2010

Updated March 2011

Updated November 2012

Updated May 2013

Updated October 2013

Updated February 2014

Updated January 2015

© COPYRIGHT Customer Owned Banking Association 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by copyright may be reproduced

or copied in any form or by any means (graphic, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopying, recording, recording taping, or information retrieval

systems) without the written permission of Customer Owned Banking Association.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

2

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Contents

PART A: Introduction ...................................................................... 4

1.

Introduction to the Guide ...................................................................... 5

2.

APRA’s role and the APRA Prudential Standards regime – an overview ...... 10

3.

The New Risk Landscape ..................................................................... 16

4.

Managing the APRA Relationship .......................................................... 20

5.

Preparing for an APRA Visit ................................................................. 23

PART B: Applying the Prudential Standards .................................. 27

6.

Capital Adequacy ............................................................................... 28

7.

Liquidity ........................................................................................... 47

8.

Credit Risk ........................................................................................ 54

9.

Audit and Disclosure ........................................................................... 61

10.

Operational Risk ................................................................................ 65

11.

Risk and Governance .......................................................................... 70

12.

Miscellaneous .................................................................................... 76

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

3

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

PART A: Introduction

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

4

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

1.

Introduction to the Guide

Who is this Guide for?

This Guide to the Prudential Standards for Authorised Deposit-taking Institutions

[ADIs] regulated by the Australian Prudential Regulatory Authority [APRA] has

been written primarily for directors of mutual ADIs. We hope it will also be useful

for senior management of mutual institutions. In addition, much of the content

will be applicable to directors and management of other, particularly smaller,

ADIs.

Background to development

The board of directors of an ADI is required to play a central role in its sound and

prudent management. This has long been recognised, and the requirement is

reflected in APRA’s Prudential Standard CPS 510 – Governance.

In our view, to meaningfully discharge your obligations as a director you must

have a good understanding of the APRA Prudential Standards regime, and be able

to apply the regime when considering and reviewing your institution’s prudential

policies (capital, liquidity, credit risk, market risk etc). This is also APRA’s

expectation. As a director, you should be able to show an appreciation of the

impact of the Prudential Standards in contexts such as prudential review

meetings with APRA (see Chapter 5).

That said the scope and complexity of the APRA Prudential Standards regime can

be daunting. This can be true even for experienced directors, including those

from professional backgrounds (e.g. accounting, law or management).

The complexity of the APRA Prudential Standards regime is due in part to the fact

that the Standards do not mandate prescriptive targets over and above the

various minimums and rules in each standard. Rather, the Standards adopt a

largely principles-based approach, requiring the board and management to apply

general principles in setting capital allocation ratios, determining liquidity

management policies, setting credit risk controls, and so on. How to interpret

the language of the Standards, and the regulator’s approach to specific issues in

practice, can be a challenge for boards and management alike. This can be

compounded by a general lack of information about the experience of other

comparable institutions (due in part to the fact that the relationship between

regulator and regulated entity is conducted, for the most part, “behind closed

doors”).

Apart from this, the Standards are not static. They continue to be modified and

extended by APRA, particularly as the standards of the international body

coordinating banking supervision, the Basel Committee of the Bank for

International Settlements, can, and do, change. We look at the implications of

some of these changes, especially the revised approach to capital adequacy

management implemented under the Basel Framework, in subsequent chapters.

Directors and management obviously need to keep abreast of changes to the

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

5

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Standards. At the same time, you must not lose your focus on other core

requirements that need to be monitored and reviewed on an ongoing basis.

Objectives of Guide

Against this background, COBA has collaborated with consultant and legal adviser

to the mutual industry, Mark Swivel, to develop a compact, practical Guide to

understanding and implementing the APRA Prudential Standards.

Our aim is to assist busy directors and senior managers to gain, retain and

refresh the knowledge of the Prudential Standards they need to make a

worthwhile contribution to corporate governance and the prudent management of

their institution.

Structure of Guide

The structure of the Guide will be apparent from the Table of Contents. In brief,

the remaining chapters of Part A provide an overview of the Prudential Standards

framework, and APRA’s role. They also consider the regulator’s expectations of

directors, and provide some tips and suggestions on managing your institution’s

relationship with, and meeting with, this key stakeholder.

The chapters of Part B then deal with the requirements of the Standards in detail

grouped around 6 thematic headings that largely follow the way the Standards

are organised by APRA.

A brief “snapshot” of each Standard is followed by commentary and examples

focussed on how the Standards operate, and strategies for achieving and

maintaining best practice compliance. The central role of the Internal Capital

Adequacy Assessment Process [ICAAP] in structuring a regime of effective

compliance with the Standards is highlighted throughout these Chapters.

Changes to APS 110 and the introduction of updated CPG 110 reinforce the

centrality of the ICAAP to prudential risk management and emphasise the active

role directors are now expected by APRA to play in capital management.

Most chapters end with a set of questions for directors and managers to

consider—emphasising the need for active involvement in decision making by

both boards and management.

Ways Guide might be used

We envisage that the Guide will be used in a variety of ways including – as an

introductory resource for new directors, as a ‘refresher’ for directors and

management (including in the context of upcoming APRA reviews etc), and

generally as a source of sector experience, best practice tips and benchmarking

information.

Development of Guide

The primary author of the Guide is Mark Swivel. Mark is a legal practitioner and

director of Swivel Pty Ltd and was a director of SCU (Sydney Credit Union) Ltd

(from 2008-11). The Guide is largely based on the author’s experience working

with mutual ADIs over many years, advising on compliance issues and writing

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

6

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

policies, and particularly in helping mutual institutions frame responses to APRA

Prudential Review Reports. COBA staff have also contributed to, and provided

comments on, drafts of the Guide.

In addition, we have benefited greatly from discussions with senior managers of

COBA member institutions about both their approaches to Prudential Standards

compliance, and the kind of resource that they, and their boards, would find

useful in helping their institutions maintain compliant prudential controls. Our

thanks go to all who have provided their input.

A living document

COBA updates this Guide periodically in light of changes to the Prudential

Standards, APRA’s regulatory approaches, your feedback on the current Guide,

and member institutions’ ongoing experience working with, and seeking to

implement, the Standards. The Guide was first published in February 2010 and

was updated in December 2010, March 2011, November 2012, May 2013,

October 2013 and February 2014 before this edition.

Guide is not a substitute for risk assessment of board and management

The Guide includes a range of worked examples, survey data, good practice tips

and other similar information. This information is intended to assist readers to

gain an understanding of how common issues are or might be approached across

the mutual ADI sector, to establish benchmarks, and to challenge current

practices of your institution where appropriate.

Of course, each ADI must develop its own risk management framework, with its

own assessment of risk profile, its own risk appetite and its own policy settings to

manage the range of risks that its unique business faces. The information

contained in this Guide is not intended, and should not in any way be seen, as a

substitute for the risk management work that each institution must itself

undertake on an ongoing basis.

Exclusions and limitations

Consistent with our target audience and objectives, the Guide does not address:

APS 222 - Related Entities; APS 240 - Credit Cards; and APS 610 - Payment

Facilities.

Note also that, while APRA permits certain large ADIs to measure capital

requirements with respect to credit risk using what is called an Internal Ratings

Based approach as an alternative to the more generally used Standardised

approach, this Guide considers the Standardised approach only. This reflects the

fact that no mutual institution is permitted to use an Internal Ratings Based

approach.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

7

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Inclusions for 2014 and 2015 editions - confirmed and proposed changes

The February 2014 edition reflected a range of changes to the prudential

standards regime including recent changes to APS 210 (Liquidity), CPS 220 (Risk

Management) and CPS 510 (Governance) with start dates in parentheses:

•

APS 110 – confirmed changes to rules on capital composition and quality

and regulatory minima and buffers for capital adequacy (January 2013)

•

APS 111 – proposed changes to the definition of regulatory capital to

enable the mutual sector’s issuance of Basel III compliant additional Tier 1

and Tier 2 instruments (October 2013)

•

CPG 110 – changes to the enhanced ICAAP framework (March 2013)

•

APS 120 – confirmed changes to securitisation (January 2013)

•

APS 121 – new prudential regulation for secured bonds (August 2012)

•

APS 210 –standard on liquidity management (1 January 2014)

•

CPS 220 –standard on risk management frameworks (1 January 2015)

•

APS 330 – provisions for public disclosure of remuneration (June 2013)

•

CPG 234 – Management of Security Risk in Information and Information

Technology (May 2013)

•

CPG 235 – Managing Data Risk (September 2013)

•

CPS 510 –changes to include the requirement to have a Board Risk

Committee (1 January 2015)

•

APS 910 – revised standard on the Financial Claims Scheme (1 July 2013).

The January 2015 edition includes commentary which reflects APRA’s 1 increased

supervisory intensity in specific areas of prudential concern including:

•

residential mortgage lending

•

capital risk weighting

•

liquidity coverage

•

securitisation.

Although proposed regulations remain in draft standards or discussion papers,

the direction of APRA’s approach is clear.

1

See for example the finalised APG 223 Residential Mortgage Lending Prudential Practice Guide released

in early November2014. In a letter dated 9 December 2014 to all ADIs, APRA discussed the regulatory

and supervisory tools it may apply to address emerging risks in residential mortgage lending practices.

See also the statement to the House Economics Committee by APRA Chair Wayne Byers on the proposed

use of so-called ‘macro-prudential’ measures such as LVR caps and loan-to-income limits together with

the possibility of increased Pillar 2 capital requirements.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

8

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Other resources

•

APRA web site – The details of the prudential standards framework can be

found here:

Prudential Standards and Guidance Notes:

http://www.apra.gov.au/ADI/ADI-Prudential-Standards-and-GuidanceNotes.cfm.

Prudential Practice Guides:

http://www.apra.gov.au/adi/PrudentialFramework/Pages/authoriseddeposit-taking-institutions-ppgs.aspx

•

The APRA site also includes general information about APRA’s role, as well

as the full text of APRA speeches, media releases and other information

referred to in this Guide.

•

COBA offers two detailed compliance manuals dealing with the APRA

governance-related Prudential Standards. They are the COBA CPS 510

Governance Compliance Manual and the COBA Fit & Proper Compliance

Manual. Your institution may already subscribe to these products. If not,

email complianceinfo@coba.asn.au for more information.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

9

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

2. APRA’s role and the APRA Prudential

Standards regime – an overview

What is APRA’s role?

APRA, which is an Australian Government statutory authority, is the prudential

regulator of the Australian financial services industry. Its responsibilities include

monitoring the financial soundness and stability of ADIs (including all credit

unions, building societies, mutual banks and banks generally) so that depositors’

interests are not compromised by the actions of the board or management of the

regulated institutions. APRA is also the prudential regulator of the insurance and

superannuation sectors.

In brief, APRA does everything it can, within its statutory mandate, to make sure

depositors’ money is safe.

How does APRA supervise ADIs in practice?

APRA’s day-to-day supervision of a mutual ADI is primarily based on these

activities:

•

Offsite analysis – ADIs must submit various reports and information in

accordance with the prudential standards and other requirements imposed by

APRA. Such submissions must include regular financial information (i.e. D2A

reports), business plans, forecasts, etc. This information is analysed and

assessed for compliance with the prudential standards regime and specific

prudential ratios as well as an input to the PAIRS risk assessment process

undertaken by APRA (see next point). APRA also receives applications for

transfers, takeovers, licensing, etc and undertakes review, oversight and

assessment of these key activities.

•

PAIRS Assessments - APRA conducts assessments for all ADIs of the

probability and potential impact of business failure, which covers the board,

management, risk governance, strategy and planning, liquidity risk,

operational risk, credit risk, market and investment risk, insurance risk,

capital coverage/surplus, earnings, and access to additional capital. This

assessment considers inherent risk, management and control, net risk and

capital support and is used by APRA in its ADI supervision action plans.

•

Prudential Reviews – APRA conducts periodic ‘reviews’ of ADIs, typically on a

bi-annual basis, or more frequently if APRA requires this (these reviews are

often referred to in the industry as ‘inspections’). The frequency of reviews is

based on APRA’s risk assessment of the entity, and the supervision action

plan in place to address the entity’s risks.

APRA also plays a major role in policy setting; and periodically, in consultation

with industry, in updating and extending the APRA Prudential Standards regime

with new standards and practice guides.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

10

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

APRA also has powers to issue directions in the event of significant noncompliance with the Prudential Standards. It can also appoint an administrator in

extreme circumstances where an ADI may no longer be a going concern.

The Prudential Standards

In simple terms, the Prudential Standards are best understood as a set of

principles designed to promote banking practices that ensure depositor’s money

is safe. From a business perspective, they can also be seen as a set of good

practice risk management principles.

There are now 24 Standards which, together with associated Guidance Notes and

Practice Guides, constitute the regulatory framework for ADIs enforced by APRA.

The main areas covered are – capital adequacy, liquidity, credit quality, large

exposures, associations with related entities, outsourcing, business continuity

management, accounting and prudential reporting, corporate governance and fit

and proper requirements (see:

http://www.apra.gov.au/adi/prudentialframework/pages/adi-prudentialstandards-and-guidance-notes.aspx.

A Snapshot of the Prudential Standards

We will consider the content of the Standards in detail in Part B of this Guide. But

here is a quick “snapshot” of what APRA requires of ADIs:

•

Capital: Minimum capital must be held as a buffer against potential losses.

Capital must be held against all the risks to which the institution is exposed.

Only certain things can count as capital - primarily profits, past and present.

Capital requirements vary depending on credit and other risk exposures. New

rules are designed to enhance the quality of capital and capital management.

•

Liquidity: Liquidity must be maintained in order to meet liabilities as and

when they fall due. Only certain things count as High Quality Liquid Assets

[HQLAs] – primarily investments held with other ADIs. Plans and funding

lines to deal with irregular events and emergencies are also required to

manage liquidity risk.

•

Business Risks: Credit risk is to be managed through good lending

practices, to minimise delinquencies and write-offs, and by appropriate

provisioning for bad debt. Market risk (interest rate risk) exposures for loans

and deposits must also be managed to protect portfolios and interest

margins. Strategic risk created by key business decisions, concentration risks

in large exposures (for credit and investments) and contagion risk from

related entities (e.g. subsidiaries), all need to be identified and minimised.

•

Operational Risk: Operational risk must be identified and managed across

the whole business of an ADI including: data risk; insurable risks (e.g.

physical assets and workers compensation); the outsourcing of key functions

to third parties; and potential business disruptions (threats to business

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

11

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

continuity). These risks require close monitoring, clear processes and

planning to avoid losses.

•

Audit and Disclosure: ADIs must implement an independent and

transparent external audit process, supported by robust internal audit and

effective board oversight. Compliance with Prudential Standards must be

reviewed by external auditors, attested to by the chief executive and

endorsed by the board. Accountability and competition is also encouraged by

mandatory public disclosure of ‘prudential information’ on capital position,

capital adequacy and credit risk, including bad debt statistics.

•

Risk and Governance: An ADI must have a risk management framework

consistent with its strategic objectives and business plan incorporating

structures, policies, processes, people and systems for identifying, measuring,

evaluating, monitoring, reporting and controlling or mitigating material risks

that may affect its ability to meet its obligations to depositors. Sound and

prudent governance is required to maintain public confidence and deliver

benefits to stakeholders. Clear strategic direction by boards, together with

professional management from executives, incorporating contemporary risk

management practices, is demanded. Directors and senior managers must

meet high standards of competence and integrity (‘fitness and propriety’).

Board oversight of risk management and financial performance is central to

good governance. Remuneration policies and oversight arrangements that

promote the long-term financial soundness of the institution must be in place.

The new standard on Risk Management (CPS 220) dovetails with the

Governance and Capital standards to reinforce the overall risk management

framework for the ADI.

The Basel II Framework

In January 2008, a new suite of Prudential Standards developed by APRA came

into operation. The new Standards give effect to the Basel II capital adequacy

standards, called the Basel II Framework, developed by the Basel Committee on

Banking Supervision 2. In general terms, the Basel II Framework, as adopted in

the Standards, aims to bring best practice in risk management into the formal

regulatory framework for managing capital adequacy.

The focus is on promoting stronger and more accurate management and pricing

of risk, including ensuring that adequate capital is allocated to support the full

range of risks assumed by the ADI. The new regime also introduced measures to

enhance transparency by requiring public disclosure of certain capital adequacy

and risk management practices information (see Chapter 9).

2

The Basel Framework is developed by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS), a

Committee of the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) which fosters international monetary and

financial cooperation and acts as a bank for central banks. The BIS is the leading policy and research

forum in the international financial community.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

12

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Basel III Framework

In late 2009, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision finalised a new capital

and liquidity framework, developed in response to the Global Financial Crisis.

Known as “Basel III”, the framework aims to improve the banking sector's ability

to absorb shocks arising from financial and economic stress, improve risk

management and governance, and strengthen banks' transparency and

disclosures. As a result, new rules have been introduced that aim to improve the

quality of capital held by ADIs and their capital management by:

•

specifying new ‘common equity’ requirements;

•

introducing capital adequacy buffers including a conservation buffer and a

counter-cyclical buffer; and

•

an enhanced ICAAP framework that provides more guidance and

prescription on how ADIs must prepare and develop their ICAAP to

support capital management (see APS 110 and CPG 110).

APRA has also proposed changes to APS 210 on Liquidity:

•

a tighter definition of HQLA (discussed in Chapter 7); and,

•

enhanced liquidity risk management requirements, including in relation to

funding plans, cash flow projections, stress testing and scenario/crisis

analysis.

Following extended consultation with COBA, in April 2014 APRA released an

updated APS 111 – Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital with amendments

facilitating additional capital-raising options for customer-owned ADIs. APRA

wrote to all affected ADIs outlining the changes to the prudential standard 3.

The revised prudential standard represents a key step in accommodating the

customer-owned model in the Basel III capital framework. The amendments were

notable because they represent the first time that APRA has explicitly

accommodated the customer-owned model in any of the prudential standards.

APRA’s implementation of the Basel III framework in January 2013 had the

unintended effect of reducing capital options for customer-owned ADIs. The

amendments restored flexibility for the sector in raising capital from other than

retained earnings. Chapter 6 of this Guide contains further discussion on this.

On 4 November 2014 APRA released a package of reforms to funding and

liquidity reporting arrangements. Reporting Standard APS 210.0 now requires all

ADIs to be able to produce daily liquidity reports on demand. COBA argued

against this for Minimum Liquidity Holdings (MLH) ADIs, a category which

includes most mutual financial institutions,but APRA believes that “the MLH

3

See letter of 15 April 2014 to all mutually-owned ADIs from Charles Littrell, APRA Executive General

Manager, Policy Statistics and International Division,

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

13

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

requirement … falls short of providing the information needed during a crisis to

build a view of an ADI’s daily liquidity position.” APRA therefore decided that “the

daily liquidity report should apply to all ADIs,” and noted that a “prudent ADI

would … generate and monitor this data as part of its existing liquidity risk

management process.”. APRA does not anticipate that daily reporting will be a

significant burden for MLH ADIs as the data is likely to be readily available.

Other changes to the Standards

There have been other changes to the Standards and their application in recent

years as well.

For instance, since 1 April 2010, all ADIs have been required to have

arrangements including a Board Remuneration Committee (or comparable

structure) and remuneration policy that ensures the remuneration of executives

and other key staff is aligned with the long-term financial soundness of the

institution and its risk management framework.

APRA has also started to apply Prescribed Capital Ratios to mutual ADIs. In its

2010 prudential reviews it generally focussed on credit risk, reminding ADIs to

preserve credit quality despite the return to better trading conditions following

the 2009 Global Financial Crisis.

APRA has also released an updated version of Prudential Standard APS 210

Liquidity, which introduces interim measures which alter the way the Committed

Liquidity Facility (CLF) applies to foreign bank branches. Several prudential

standards have been consolidated so that they are now identical for the different

entities regulated by APRA i.e. ADIs and non-ADIs.

APRA has introduced new cross-industry standards for risk management

generally which will require ADIs to formalise their risk management framework,

appoint a Chief Risk Officer and establish a Risk Management Committee. These

new requirements are set out in CPS 220 Risk Management and an updated

version of CPS 510 Governance. They were not fully effective until 1 January

2015. However, ADIs were expected to develop implementation plans to ensure

that regulated entities are able to meet all requirements by 1 January 2015.

These are significant (but long-anticipated) changes to the substance of ADI

prudential risk management obligations. Note also there are consequential

amendments to the following standards to reflect the changes introduced by the

new cross-industry standards for risk management:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

APS

APS

APS

APS

APS

APS

APS

001

116

120

210

220

221

222

Definitions

Capital Adequacy: Market Risk

Securitisation

Liquidity

Credit Quality

Large Exposures

Associations with Related Entities

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

14

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

APS 310 Audit and Related Matters

APS 330 Public Disclosure

APS 610 Prudential Requirements for Providers of Purchased Payment

Facilities

CPS 231 Outsourcing;

CPS 232 Business Continuity Management;

GPS 001 Definitions;

GPS 110 Capital Adequacy;

GPS 113 Capital Adequacy: Internal Model-based Method;

GPS 310 Audit and Related Matters

GPS 320 Actuarial and Related Matters;

LPS 001 Definitions; and

LPS 320 Actuarial and Related Matters

Chapter 12 was also added in 2013 to the Guide to cover new prudential

standards APRA has introduced to address specific issues facing industry:

•

•

APS 121 – Covered Bonds

APS 910 – Financial Claims Scheme

On the Horizon

On 18 September 2014 APRA released for consultation a discussion paper and

draft amendments to APS 110 Capital Adequacy and APS 330 Public Disclosure

which outlined APRA’s proposed implementation of new disclosure requirements

for ADIs. The proposed disclosures are in relation to the leverage ratio, the

liquidity coverage ratio and the identification of globally systemically important

banks. The consultation package also proposes minor amendments to rectify

minor deviations from the Basel III framework.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

15

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

3.

The New Risk Landscape

The role of boards in risk management is increasingly demanding. We are now a

long way from the days of volunteer directors who relied on management to ‘run

the business’. Contemporary business culture places the boards of ADIs and

other businesses at the centre of risk management. In the case of ADIs, the

Prudential Standards strongly reinforce this trend, the more so since the

Standards were revised in 2008 to implement the Basel II Framework (see

Chapter 2).

For mutual ADI managers, risk management also requires new skills that reach

beyond the competencies of bread and butter banking.

Risk Management Framework – CPS 220

CPS 220 articulates long-standing informal expectations for ADI risk

management. From January 2015, an ADI Board must have in place a risk

management framework (RMF) appropriate to its size, business mix and

complexity that is consistent with the ADI’s strategic objectives and business

plan.

The RMF will overlay the specific risk systems e.g. policies for capital, liquidity,

market and other risks and must include a board approved:

•

risk appetite;

•

risk management strategy that describes the key elements of the RMF that

give effect to its approach to managing risk;

business plan that sets out its approach for the implementation of its strategic

objectives;

In practice, an RMF should be closely aligned with the ICAAP and APS 310

declaration for the ADI.

•

The ADI must also maintain adequate resources to ensure compliance with CPS

220 and notify APRA of significant gaps in, breaches of or material deviations

from the RMF.

Impact of ICAAP

As part of your institution’s compliance with the Prudential Standards post-Basel

II, it must develop, document and maintain a comprehensive Internal Capital

Adequacy Assessment Process [ICAAP], proportional to its operations and

consistent with APRA’s requirements. In brief, the ICAAP is the APRA-mandated

process for ensuring ADIs take an integrated whole-of-enterprise approach to

allocating capital as a buffer against potential losses. The ICAAP is discussed

further in Chapter 6 on Capital Adequacy, and referred to throughout Part B of

the Guide.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

16

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Until ICAAP, the Prudential Standards regime could be interpreted as a diverse

range of rules and requirements dealing with separate topics. ICAAP changes

that by bringing each risk type under the one umbrella and allocating prudential

capital for each risk. For example, liquidity risk is no longer just a matter of

meeting minimum standards for HQLA. It now also requires the allocation of an

amount of capital, considering potential threats to liquidity and the costs incurred

by your ADI if those costs materialise.

Your ICAAP can now be used as the centrepiece of your institution’s Prudential

Standards risk management framework. As part of this, all the directors of your

institution should be familiar with the details of your ICAAP. Under the Basel III

changes, directors are now expressly required to understand and be actively

engaged in the development and monitoring of your ICAAP (see CPG 110 and

CPS 220).

Risk and Strategy

Strategy drives risk. APRA will expect all directors and managers to see and

understand the linkage. Your risk management framework must acknowledge

the strategy of the organisation. At the same time, risk should be incorporated in

your strategic planning.

Risk is present whether your strategy is ‘adventurous’ or ‘cautious’. If an ADI

commits to an aggressive growth strategy, risk increases. For example, a

growing loan book can put pressure on capital adequacy; stretching targets may

threaten loan quality and undermine sales processes; and liquidity may be

challenged by spikes in loan funding. On the other hand, risk does not go away if

an ADI adopts a more ‘conservative’ strategy and commits to consolidating its

position. For example, the ADI may lose its relevance; it may stagnate as it tries

to ‘fly under the radar’; it may lose members, loans and deposits, and as a

consequence costs may increase while income and profits can fall.

Be honest about risk

Risk is everywhere. Even in the best-run businesses and ADIs, risks are inherent

to all activity. The question is whether the risks are identified and managed by

the board and management team. So, if there’s a golden rule about risk, it might

be ‘be honest and up front’ and acknowledge the importance of risk. For

example, even if delinquency is currently low and write-offs have been

historically negligible, the risk of default remains a key business risk for any ADI.

Risk Appetite Statement

There is no formula for describing the risk appetite of an ADI; however, the

prudential standards now require a formal risk appetite statement for all ADIs

(see APS 110, CPG 110 and CPS 220). Each ADI must articulate its own risk

appetite as part of its risk management. You should already have the ‘spirit’ of

your risk appetite expressed in your existing policies.

The key requirements for the Risk Appetite Statement (RAS) of an ADI are set

out in CPS 220:28-30. The RAS must address material risks including: credit

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

17

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

risk; market and investment risk; liquidity risk; insurance risk; operational risk;

risks arising from strategic objectives and business plans; and other risks that

may have a material impact on the ADI.

The RAS must outline:

•

the degree of risk the ADI is prepared to accept in pursuit of its strategic

objectives and business plan, giving consideration to the interests of

depositors and/or policyholders (risk appetite);

•

for each material risk, the maximum level of risk that the ADI is willing to

operate within, expressed as a risk limit and based on its risk appetite, risk

profile and capital strength (risk tolerance);

•

the process for ensuring risk tolerances are set at appropriate levels, based

on estimated impacts and likelihood of breaches;

•

the process for monitoring compliance with risk tolerances and for taking

action in the event of breach; and

•

the timing and process for reviewing risk appetite and tolerances (CPS

220:28-29).

Each ADI must articulate its own risk appetite as part of its risk management.

You already have the ‘spirit’ of your risk appetite expressed in your existing

policies.

Although all mutual ADIs are different, the core business model tends to produce

similar risk appetites as shown in these typical elements or business

characteristics:

•

Product range – ‘vanilla’ savings, loan and payment products

•

Non standard products – limited use of non-core products (e.g. insurance)

•

Loan portfolio composition – high ratio of mortgages to personal loans, low

average loan-to-value ratios (LVRs)

•

Deposit portfolio composition – ratio of savings to term deposits

•

Credit quality – concentration of assets in secured lending, conservative debt

servicing ratios, limited commercial lending

•

Pricing strategy – competitive but not market leading interest rates

•

Property holdings – limited exposure; generally small scale commercial

properties

•

Staff culture and incentives – emphasis on service and strong control culture

•

Cost to income ratios – generally high ratios across the sector (relative to

banks), primarily due to staffing and branch costs

•

Capital and other prudential ratios – operating well above statutory

minimums.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

18

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Alternatives to these norms can be found in organisations that pursue aggressive

growth targets, subsidiary businesses, non-core businesses, high concentrations

of commercial lending, and atypical strategic alliances.

Other tips on risk management

Don’t make risk a chore. Risk management is good management.

The Prudential Standards should be approached as statements of good practice.

Each standard establishes minimum levels of requirements and behaviour only.

Every ADI must set its own policy rules based on its risk appetite, culture and

risk management systems.

Your prudential standard compliance system should also be aligned with other

compliance systems e.g. for consumer credit, AML, privacy and AFS licensing.

Good practice in compliance involves creating a compliance ‘culture’ in the

organisation, sponsored by the board and driven through the organisation by

management. For more on Compliance Programs see AS 3806-2006.

See also “The importance of a risk management strategy” in Kiel et al Directors

At Work: A Practical Guide for Boards (Thomson Reuters 2012 p 352); and COBA

publication The Decisive Board “The Board Risk Committee” (July 2014 issue).

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

19

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

4. Managing the APRA Relationship

Mutual ADIs should approach the relationship with confidence

In an address to the COBA and AM Institute Convention held in Melbourne in

October 2013, Dr John Laker, outgoing APRA Chairman, acknowledged the strong

performance of mutual ADIs despite the 2009 Global Financial Crisis. Dr Laker

observed :

” Mutual ADIs have emerged from this period and what was no doubt a very

unsettling experience during the worst of the crisis, in solid shape. As a sector

mutual ADIs have continued to grow balance sheets sensibly, earn good profits

(around $450 million in 2012/13) and maintain healthy capital positions. No

mutual ADI failed during the crisis and no mutual ADI breached any of APRA’s

key prudential requirements. A record to be proud of and one that mutual

movements in other countries must envy” 4

Dr Laker’s remarks suggest that mutual ADIs have effective risk management

systems in place. Although there is no cause or room for complacency, mutual

ADIs can approach the relationship with APRA with confidence.

APRA’s expectations of the board of directors

APRA has long seen the role of the board as central to the governance of mutual

ADIs. The position is now clearly stated in CPS 510:

The Board of directors [of an ADI] is ultimately responsible for the sound and

prudent management [of the ADI].

APRA expects the board of a mutual ADI to:

•

understand their business;

•

be capable of identifying, monitoring and managing the risks associated with

that business;

•

anticipate and respond to emerging risks; and

•

approve and oversee implementation of risk-based policies.

Given these expectations, a modern mutual ADI board should:

•

invest in risk management (internally and externally);

•

implement and oversee a comprehensive risk management framework;

•

conduct regular policy reviews; and

•

pro-actively engage APRA and other regulators.

What should a director be doing about Prudential Standards compliance?

Directors must actively participate in the governance of ADI. To do this

meaningfully, as a contemporary director you must be able to:

4

Mutuals : a look back and ahead – John Laker, COBA Convention, Melbourne , 29 October 2013 p 1

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

20

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

•

understand the APRA Prudential Standards regime 5;

•

understand your own policies especially capital, liquidity, market risk and

credit risk; and

•

contribute to the strategic risk management process.

What should Risk Committee members (and the chair) be doing?

Although the board as a whole is ultimately responsible for the risk management

function, the Risk Committee members should probably be doing a little more

work than other directors in this area. They should have a good working

knowledge of the details of all Prudential Standards and Guides. The chairs of

the board, Audit Committee and Risk Committee should seek to develop good

working relationships with their contacts at APRA 6.

Communication with APRA – some tips and ideas

Many mutual ADIs maintain effective relationships with APRA. ADIs reporting

‘good experiences’ with APRA emphasise the importance of proactive

communication with their APRA contacts.

Communication and openness can build rapport and an effective relationship with

your regulator.

Here are some ‘common sense’ ideas and tips for better communication with

APRA:

•

Pick up the phone: There’s no need to wait for the phone to ring. ADIs are

free to call APRA and discuss their business and any concerns. For example,

your institution might contact its APRA supervisor on a quarterly or even

monthly basis to discuss your D2A report and current issues in the business,

as well as your institution’s responses to issues raised in the most recent

APRA inspection report.

•

Visit your regulator: There’s no need to wait for an inspection. Some ADIs

already meet with APRA on a regular basis whether at APRA’s offices or yours.

You might prepare a presentation once or twice a year to make sure APRA

knows where your business is going, the state of your prudential ratios and

your appetite for risk.

•

Policy reviews: There’s no harm in telling APRA about policy reviews as they

happen. As you work through your annual policy review schedule, why not

send APRA an email to remind them that your policy review has been

completed, with a summary of the changes made.

5

APRA wrote to all ADI directors on 7 October 2014 clarifying the requirements it imposes on boards by

the prudential standards: http://www.apra.gov.au/CrossIndustry/Documents/Letter-to-industryimproving-APRA-board-engagement-October-2014.pdf

6

For a detailed discussion of the functions of the Board Risk Committee see the COBA publication The

Decisive Board. July 2014.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

21

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

•

Keep APRA in the loop: The regular D2A report provides a lot of information

to APRA. However, some ADIs provide a more frequent report. In one case, a

credit union sends APRA a weekly ‘dashboard’. That’s a good example of

keeping your regulator in the loop.

Developing a “dashboard” update for APRA

Your institution might consider a monthly email to APRA that includes the

following prudential and financial metrics:

Mutual ADI

Prudential

Internal

Current

APRA Update – Dashboard

Limit

Strategic Target

Position

/ Policy Limit

Capital Adequacy Ratio

8%

12.5-15%

14.5%

PCR / ICAAP

12% (PCR)

9% (ICAAP)

14.5%

Common Equity Tier 1 Minimum

4.5%

8%

14.5%

Liquidity – HQLA

9%

11-25%

20.25%

Interest rate risk (NPVBP)

NA

5%

2.75%

Delinquency > 30 days

NA

<1%

0.75%

General Reserve for Credit Losses

NA

0.50%

0.75%

Return on Assets

NA

1%

0.75%

Asset Growth

NA

5% p.a

8.25% p.a.

Cost to Income Ratio

NA

75%

77.5%

Commercial Lending (% of

NA

5%

2.5%

NA

2.5-3.5%

3.55%

portfolio)

Interest Margin

[The sample provided is for illustrative purposes only]

Note: the sample policy limits included in the table above provide an example of

how to approach compliance with the new requirements to articulate risk

tolerances: CPS 220:30.

Questions for directors and senior managers to consider

How could you improve your communications with APRA?

Could you use a dashboard to report to APRA more regularly?

What could you do to enhance your understanding of risk management?

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

22

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

5. Preparing for an APRA Visit

Planning Meeting – before the prudential review

The board and management should meet to discuss their approach to the

meeting with APRA. APRA will send a letter outlining the agenda for the

inspection and a list of information required by them before and during the visit.

Management will largely attend to the response but the board should be engaged

with the process. Here is a recommended approach for organising your response

to a prudential review or ‘inspection’:

•

Review the APRA ‘Prudential Review’ letter including agenda and information

required by APRA – discuss the board and management response to each

item clarifying current practices, identifying potential discussion points, and

the documentation that will assist your response.

•

Review the ‘Board and Governance’ section and agree an approach e.g.

dividing topics among directors. Consider developing a presentation to

address the matters raised (see further below).

•

Review the APS 310 declaration – the annual statement on key risks made by

the CEO and endorsed by the board, which should ideally be a summary of

the work conducted by the board or risk management committee throughout

the year.

•

Ensure all policy reviews are complete, particularly the ICAAP – and ensure all

directors understand the elements of the ICAAP and allocation of capital for

specific risks (strategic, credit, interest rate, liquidity, operational etc).

•

Ensure all outstanding items from previous reviews, and issues raised in

subsequent correspondence, have been acted on and implemented including

changes to policies and procedures.

Your approach might well be guided by APRA’s comments on the process. For

instance, the following comments were made by Stephen Glenfield at the COBA

Convention 2009:

•

Treat the review as an opportunity—show you know what you are doing,

and where you are going

•

Be transparent—don’t just hope APRA won’t find it

•

Consider outstanding matters from past/reviews/ audit reports—what has

your institution done about these?

•

What are your institution’s current issues or problems—and, most

importantly, what are you doing about these?

•

What is “Plan B” if your current strategy encounters problems—be

sensible!

Director Preparation - What should directors know?

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

23

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

To prepare for an APRA visit, a director of a mutual ADI should revise:

•

The basics of each Prudential Standard—this Guide can assist you here;

•

Your policy guidelines and risk management framework; and

•

The current position of the ADI for each key prudential ratio (especially

capital, liquidity, interest rate risk, delinquency, provisioning).

Most mutual ADIs now have an intranet holding all policies and the organisation’s

risk management framework. The data on key prudential ratios – for the last 12

to 24 months - should be found in your most recent board papers.

Champions: Many mutual ADIs appoint “champions” for particular risk areas.

While everyone must have a general knowledge of the standards and policies, the

appointed ‘experts’ can delve deeper into the detail of the separate topics.

Directors Prudential Review Meeting With APRA

APRA will usually ask directors to attend a meeting with APRA representatives as

part of a prudential review. The agenda will be provided in advance. This will set

out APRA’s expectations for the session, which will usually last for 2 or 3 hours.

The meeting will usually be conducted without management present.

To assist the process, the board may wish to develop a presentation, with

different directors talking to different topics, including:

•

Governance structure – board charter, committees, strategic planning and

budgeting processes

•

Overview of strategic plan, risk profile and risk appetite

•

Key performance metrics (from strategic plan and business plan/budgets)

•

Major initiatives (e.g. new business areas, mergers, strategic alliances)

•

Approach to capital, liquidity, credit risk, market risk, operational risk

APRA wants to see a proactive and engaged board that understands its strategy

and the associated risks. Directors should be able to show an appreciation of the

impact of the Prudential Standards, the performance of the organisation and the

risk management outlook for the foreseeable future.

In particular, APRA expects to see a “joined up” and consistent approach to risk

across the institution’s strategy, policy and implementation. It is probably not

good practice, for example, to say that your institution has a low risk appetite if

you are about to launch a new commercial lending arm.

From 2013, directors can reasonably expect APRA to emphasise the content,

development and understanding of the ICAAP in their reviews. Although not all

directors will need to be involved in the technical formulation of the ICAAP,

everyone must have a solid understanding of what it means for capital

management and strategy, both for the current operating environment and the

future as seen by the organisation.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

24

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

The post-Prudential Review letter from APRA

After the visit, APRA will issue a letter setting out a range of issues for action

designed to enhance your institution’s risk management framework. The actions

will usually be described as one of the following:

•

Requirements—these are effectively mandatory;

•

Recommendations—what APRA sees as best practice, and wants to

encourage your institution to adopt. These need to be seen, inter alia, in

the context of your institution’s broader relationship with the regulator;

and

•

Suggestions—optional actions that may improve your institution’s

approach to risk management.

Each action raised by the APRA letter must be addressed. The board and

management must respond in writing outlining the actions taken in response to

each item. You may not agree with every item, or the reasons behind it. But

where you want to tell APRA you do not agree, make sure your response is a very

clear and reasoned one.

Again, transparency and effective communication is paramount when responding

to the APRA letter.

APRA terms explained in detail

Requirement - If an action is classified as a “Requirement”, the entity must

undertake specific action to address the associated matter. Typically, matters

resulting in a “Requirement” will relate to either the entity’s failure to comply

with legislation or prudential standards, or a fundamental deficiency in the

entity’s risk management and/or governance practices. A general failure by the

entity to act on a “Requirement” may result in APRA exercising legislative or

prudential remedies.

Recommendation: If an action is classified as a “Recommendation”, the entity is

expected to consider formally the implementation of what is being put forward.

Typically, matters resulting in a “Recommendation” will relate to areas of risk

management and/or governance that whilst not fundamentally deficient, could be

improved. A general failure by the entity to implement “Recommendations” may

result in a higher risk rating being assigned and, potentially, in APRA exercising

legislative or prudential remedies.

Request for Additional Information: If an action is classified as a “Request for

Additional Information”, the entity is required to provide that information within

the specified timeframe. Typically, matters resulting in a “Request for Additional

Information” will relate to areas where information was either absent, incomplete

or inconclusive. A general failure to respond to a “Request for Additional

Information” may result in APRA, without further warning, issuing formal

legislative notices requiring the production of information or documents.

Subsequent follow-up action may be necessary depending on APRA’s assessment

of the information supplied.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

25

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Suggestion: If an action is classified as a “Suggestion”, this represents the

opportunity for the entity to move towards better practice. Subsequent follow-up

action in relation to suggestions is usually performed in the context of better

practice considerations and does not involve timeframes for implementation.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

26

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

PART B: Applying the

Prudential Standards

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

27

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

6. Capital Adequacy

Active capital management - evolving approaches to ICAAP and capital allocation

for risks

Capital is the cornerstone of an ADI’s financial strength. It supports an ADI’s

operations by providing a buffer to absorb unanticipated losses from its

activities and, in the event of problems, enables the ADI to continue to

operate in a sound and viable manner while the problems are addressed or

resolved: APS 110:7. The board of directors of an ADI has a duty to ensure

that the ADI maintains a level and quality of capital commensurate with the

type, amount and concentration of risks to which the ADI is exposed from its

activities. In doing so, the board must have regard to any prospective

changes in the ADI’s risk profile and capital holdings: APS110:9.

Capital Adequacy - Objectives and key requirements

APS 110: An ADI must maintain adequate capital to act as a buffer against the

risks associated with its activities. APS 110 outlines the overall framework for

APRA’s assessment of the capital adequacy of an ADI. The updated key

requirements of APS 110 are that an ADI must:

•

have an ICAAP;

•

maintain minimum levels of capital;

•

operate a capital conservation buffer and, if required, a countercyclical capital

buffer;

•

inform APRA of any adverse change in actual or anticipated capital adequacy;

and

•

seek APRA’s approval for any planned capital reductions.

Basel III also changes the details of capital adequacy rules. From 1 January

2013, an ADI must hold a prescribed capital ratio based on risk weighted assets

of:

•

a Common Equity Tier 1 Capital ratio of 4.5 per cent;

•

a Tier 1 Capital ratio of 6.0 per cent; and

•

a Total Capital ratio of 8.0 per cent.

APS 110 also introduces capital buffers that operate over and above these

minima. When managing capital, ADIs will be required – from 1 January 2016 to factor in:

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

28

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

•

A capital conservation buffer (to ensure prudential capital management and

avoid breaching the PCR or ICAAP); and

•

A counter-cyclical buffer (if and when required by APRA).

The revised APS 110 also now explicitly mentions ‘risk appetite’ and notes

‘Capital management must be an integral part of an ADI’s risk management, by

aligning its risk appetite and risk profile with its capacity to absorb losses (APS

110:8).

“The mutual ADI sector has a substantial buffer of high-quality capital above

APRA’s prudential requirements to cope with financial stress…On current

holdings mutual ADIs will also easily pass the second milestone on 1 January

2016, when the new capital conservation buffer comes into effect” Mutuals : a

look back and ahead – John Laker, address to COBA Convention, Melbourne ,

29 October 2013 p 6

APS 111: APS 111 sets out the essential characteristics that an instrument must

have to qualify as either Common Equity Tier 1, Additional Tier 1 or Tier 2 capital

for inclusion in the capital base. The new concept of Common Equity essentially

means ordinary shares or retained earnings. Remember that mutual ADI capital

is almost entirely made up of profits – retained and current. Additional Tier 1

capital supplements Common Equity but the capital instruments must comply

with strict conditions to qualify.

Tier 2 capital falls short of the quality of Tier 1 capital but contributes to the

overall strength of the ADI as a going concern. The capital base is the sum of

Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital after deductions. The key requirements of APS 111 are

that an ADI must:

•

only include eligible capital as a component of capital for regulatory capital

purposes; and

•

make certain deductions from capital (e.g. for shares in other ADIs and

companies, investments in CUFSS and intangible assets).

Prior to April 2014 the ‘viability’ provisions of the APS 110/111 made it difficult

for mutual ADIs to create Additional Tier 1 instruments because of the general

requirement for capital instruments to be able to convert into common equity

(which for mutual or customer owned ADIs is limited to member share capital)

e.g. in the event of winding-up. In April 2014 APRA released the final amended

Prudential Standard APS 111 Capital Adequacy: Measurement of Capital (APS

111), which allows mutually owned ADIs to issue Additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier

2 (T2) Capital instruments that will qualify to be included in Common Equity Tier

1 (CET1) Capital provided they meet the requirements in Attachments B, F, J and

K of APS 111.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

29

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

To qualify, the capital instruments must provide for conversion into mutual equity

interests (MEI) in the event that the loss absorption or non-viability provisions in

these instruments are triggered.

Conversion into ordinary shares is not possible for mutual ADIs due to their

mutual corporate structure.

The conditions for the qualifying instrument include the requirement for mutual

equity interests to provide no voting rights (other than as required under the

Corporations Act) and to limit both the claim of mutual equity interest holders on

any surplus of a failed mutual ADI and the amounts that can be paid by way of

dividends to these holders.

Prior to the issue of any eligible Additional Tier 1 or Tier 2 Capital instrument

whose terms provide for conversion to mutual equity interests, the issuer must:

(a) have a constitution that permits the issue of mutual equity interests and the

terms of the issue must be consistent with the issuer’s constitution;

(b) have obtained approval from its members, if required by the issuer’s

constitution, to the issue of mutual equity interests if the prescribed events

occur;

(c) have obtained approval from members, if required by the issuer’s

constitution, for the terms of issue of mutual equity interest; and

(d) have obtained any relief considered by the ADI to be necessary under Part 5

of Schedule 4 of the Corporations Act for the issuance of mutual equity interests.

For further details refer to APS 111 available at

http://www.apra.gov.au/adi/Documents/20140408-APS-111-(April-2014)revised-mutual-equity-interests.pdf.

Note: the impact of the Basel III changes on Additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital

instruments needs to be considered by each ADI; and APRA should be consulted

to determine the treatment of all existing instruments.

APS 112: An ADI must hold sufficient regulatory capital against credit risk

exposures (i.e. loans and investments). The key requirements of APS 112 are

that an ADI:

•

must apply risk-weights to on-balance and off-balance sheet exposures based

on credit rating grades or fixed weights broadly aligned with the likelihood of

counterparty default; and

•

may reduce the credit risk capital requirement where the asset or exposure is

secured against eligible collateral or supported by mortgage insurance from

an acceptable lenders mortgage insurer.

Risk weighting varies depending on the risk of an exposure. As a result:

•

Mortgages are weighted at 35% to 100% depending on the LVR and whether

lenders mortgage insurance (LMI) applies (see table below);

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

30

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

•

Personal loans and commercial loans are always 100% risk weighted;

•

Loans 90 days past due are weighted at 100% for mortgage secured loans

and other loans where specific provision is more than 20% of the outstanding

balance; and up to 150% for other loans where specific provision is less than

20%; and

•

Investments in ADIs are risk weighted at 20% (where the term is no more

than 3 months and the ADI has a credit rating grade of 1, 2 or 3).

Off balance sheet exposures are weighted at 100% for commitments with certain

drawdown, and 50% for other undrawn commitments with a residual maturity of

more than 1 year.

Deductions are made from capital for investments in other ADIs (e.g. shares in

Cuscal, Indue or ASL) and advances made to CUFSS, the credit union industry

liquidity support scheme.

In a speech on * September 2014 APRA chair Wayne Byres observed there was

an increasing lack of faith in internal models used for calculating risk weights,

noting that: “Unless investors have faith in the resulting risk-based capital ratios

they do not serve their full regulatory purpose. And if that is the case simpler

metrics will inevitably become more important and potentially even binding”.

In January 2015 the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) released

consultation papers 7 on credit risk and capital floors, which propose changes to

the risk weights for residential mortgages and bank exposures.

Currently, a flat 35% risk weight is applied to residential mortgages. The BCBS

paper expressed concern that this approach “lacks risk sensitivity” and has

proposed introducing incremental weights ranging from 25% to 100%. The risk

weight of a loan would be determined by its LVR and debt service coverage

(DSC) ratio (see table below) based on the borrower’s after-tax income.

The BCBS has also proposed moving away from credit ratings in determining risk

weights for “bank” exposures. Instead, risk weights would use a sliding scale

based on the capital adequacy and asset quality of the bank to which the

institution was exposed.

Key points from the proposal include:

•

The lowest risk weight would be 30% compared to the current 20%

•

Risk weights for customer owned ADIs could be lower than major banks,

because a CET1 ratio of 12% or more is required for the lowest risk weight.

The BCBS reforms are ultimately likely to be implemented in Australia, however it

is expected to be at least two years before any possible changes flowing from

these proposals are adopted by APRA.

7

See http://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d307.pdf and http://www.bis.org/bcbs/publ/d306.pdf

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

31

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Mortgage Risk Weighting for Capital Adequacy Calculations

Loan to Value ratio

No Lenders Mortgage

Lenders Mortgage

Insurance %

Insurance %

0-60%

35

35

60-80%

35

35

80-90%

50

35

90-100%

75

50

100%+

100

75

Please note: APRA has foreshadowed potential changes to asset risk weighting for

capital adequacy purposes but at the time of writing the detail remains to be

finalised.

APS 114: An ADI must also hold sufficient regulatory capital against operational

risk exposures. The key requirements of APS 114 are:

•

an ADI must divide its activities into three areas of business: retail banking,

commercial banking, and all other activity;

•

the total capital requirement for operational risk is the sum of the capital

requirements calculated for each of the three areas of business.

The capital requirement is based on assets and income and is calculated using a

standard formula. For retail/commercial banking, the formula is based on gross

outstanding loans and advances over the previous 6 half-yearly periods. For all

other activities, it is based on net income earned. The capital charge is the

average of those 6 observations: APS 114:18.

Note: APS 113 - Internal Ratings based Approach to Credit Risk, APS 115 Advanced Measurement Approaches to Operational Risk, APS 116 - Market Risk

and APS 117 - Interest Rate Risk in the Banking Book do not generally apply to

mutual ADIs because either: these Standards apply to ADIs using an Internal

Ratings based approach (rather than the Standardised approach); or mutual ADIs

do not have a “trading book”. However, market risk and interest rate risk must

be incorporated in an ADI’s risk management framework and the ICAAP. Market

risk is separately considered at the end of this chapter.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

32

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Capital Adequacy Ratios

To calculate the capital adequacy ratio for an ADI, you divide capital by riskweighted assets.

Capital

Risk Weighted Assets

Capital – is your accumulated reserves, mainly profits, generated over the years,

plus additional sources of capital (e.g. subordinated debt and the general reserve

for credit losses), less deductions (e.g. investments in Cuscal or Indue or ASL

and loans to CUFSS).

Risk Weighted Assets – are mainly mortgages and other loans and investments

‘weighted for risk’. Risk weighted assets are calculated using the formulae set

out in APS 111 (see table on previous page) – which reduces the assets against

which you must hold capital. Risk weighted assets tend to be around half of total

assets.

The statutory minimum for total capital adequacy is 8% of risk-weighted assets.

Most banks operate around 8%. Most mutual ADIs operate well above that level:

APRA may prescribe a ‘Prudential Capital Ratio’ – and it is increasingly doing so

for mutual ADIs. From 1 January 2013, ADIs will also have to track the minimum

levels of Common Equity Tier 1, Additional Tier 1 and Tier 2 Capital.

From 1 January 2016, the introduction of capital conservation of 2.5% of riskweighted assets and counter cyclical buffers of ‘up to’ 2.5% of risk-weighted

assets will need to be factored into capital adequacy calculations.

In practice each ADI must apply the capital conservation buffer; while the

‘counter-cyclical’ buffer would only be applied at the discretion of APRA, with the

level of the buffer determined by APRA for each ADI based on deteriorating

economic conditions and prospects.

ICAAPs in Practice

An ICAAP requires a plan and policy for the calculation of appropriate levels of

capital given particular risks facing the business. Operational risk has a specific

charge but otherwise there is NO prescribed capital amount to be held for any

particular risk (e.g. credit, liquidity, interest rate). An ICAAP will itemise a capital

allocation for each risk identified (usually expressed as a percentage of capital)

as shown in Examples 1 and 2 below.

Remember: when your institution is setting an ICAAP ratio it is saying in effect:

“This is the amount of capital we believe is necessary for the business to hold to

cover us in the event of future losses, based on our strategy, our past

performance and our expectations for the market and the business.”

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

33

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

With the advent of CPS 220, an ICAAP must be aligned with the Risk Appetite

Statement for the ADI. An ICAAP should already address the key risks itemised

in CPS 220:28 and the requirements for risk appetite and tolerances in CPS

220:30.

The New ICAAP: APS 110 and CPG 110

APRA has updated its ICAAP requirements to reflect good practice internationally

and ensure that:

•

an ICAAP includes stress testing and scenario analysis;

•

appropriate processes are implemented for reporting to the board on the

ICAAP and its outcomes;

•

an ICAAP includes a summary statement and policies to address material

risks not covered by explicit regulatory capital requirements; and

•

an ICAAP report is submitted by all ADIs to APRA annually.

Despite the breadth and minutiae of the changes, actual capital risk management

should not be materially changed by the new ICAAP. The emphasis here is on

refining the ICAAP process. Moreover, the changes generally either reflect

existing practice that mutual ADIs should already be following or formalise the

approach taken by APRA in supervising capital management in practice in recent

years.

Revised ICAAP Requirements

An ICAAP must now include or address:

•

Stress testing and scenario analysis – these must be incorporated in the

methodology

•

Reporting - to the board of the ADI and ensuring the ICAAP is incorporated in

business decisions

•

Material risks – not covered by explicit capital requirements

•

A summary statement - summarising the complete ICAAP.

Additional obligations under APS 110 include:

•

An independent ICAAP review must be conducted every 3 years by

appropriately qualified persons

•

Annual ICAAP reporting to APRA by the ADI including 3 years of capital

projections

•

Annual declaration by board and management on the ICAAP.

Boards must oversee the updating of ICAAPs, the creation of new processes and

reports and the implementation of the new ICAAP.

© Customer Owned Banking Association – January 2015

34

Making Sense of the Prudential Standards

Compliance with the new ICAAP generally and in particular the obligations

regarding stress testing and scenario analysis may stretch the technical

knowledge of some directors. Consequently enhanced training on ICAAPs may be

required.

CPG 110 Content

The ICAAP methodology is not prescribed but CPG 110 provides substantial

guidance on the approach that APRA expects ADIs to take. CPG 110 also

underlines the expectation that directors need to be more ‘hands on’ with the

ICAAP, e.g.:

•

‘the capital standards require the board to be actively engaged in the

development and finalisation of the ICAAP and the oversight of its

implementation on an on-going basis’; and

•

‘APRA expects the board to robustly challenge the assumptions and

methodologies behind the ICAAP and associated documentation’.

CPG 110 articulates that the risks covered by the ICAAP should include (as

relevant to the ADI):

•

credit risk, liquidity risk, market risk, interest rate risk in the banking book

and risks associated with securitisation; and

•

operational risk, strategic and reputational risks and contagion risks. Other

risks may be relevant for individual regulated institutions and, if so, will

ordinarily be considered in the ICAAP.

An ICAAP should set capital adequacy ‘target levels’ by taking into account (as

relevant to the ADI):

•

the risk appetite of the regulated institution;

•