International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

International Business Review

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ibusrev

Effect of export experience and market scope strategy on export

performance: Evidence from Poland

Jerzy Cieślik a,*, Eugene Kaciak a,b,1, Narongsak (Tek) Thongpapanl b,c,2

a

Center for Entrepreneurship, Kozminski University, Jagiellonska 59, Warsaw, Poland

Goodman School of Business, Brock University, St. Catharines, ON, Canada L2S 3A1

c

Chiang Mai University, Chiang Mai 50200, Thailand

b

A R T I C L E I N F O

A B S T R A C T

Article history:

Received 10 April 2014

Received in revised form 5 February 2015

Accepted 13 February 2015

Available online 29 March 2015

This study examines the impact of internationalization experience and market scope strategy on the

export performance of firms operating in Poland. This study uses data from 2003 to 2010, an eight-year

period that includes the country’s accession into the European Union in 2004. Several important findings

are revealed by the research. First, a firm’s export experience and performance have an inverted Sshaped relationship, i.e., performance is increasing at low and high levels but decreasing at moderate

levels of experience. Second, the relationship between the growth of the number of export countries and

export performance is initially positive, but becomes negative over time. Third, over time the growth of a

firm’s share of the main export market is found to be negatively related to export performance. Revealing

the dynamism of these relationships through a longitudinal approach is of theoretical and practical

importance to scholars, practitioners and governments of other emerging economies that are

considering joining similar trade organizations/agreements.

ß 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Emerging economy

Export experience

Export marketing strategy

Export performance

Inverted S-shaped relationship

1. Introduction

As international competition increases, it is important for firms

to develop and implement successful strategies in order to ensure

satisfactory export performance outcomes (Casey & Hamilton,

2014; Laufs & Schwens, 2014). How and why some firms succeed in

certain foreign markets, while others fail, is one of the critical

issues in international strategic management (Beleska-Spasova,

Glaister, & Stride, 2012). Certainly degree, scope and speed, the

three most important strategic dimensions of international

entrepreneurship as defined by Zahra and George (2002), play a

role in the success or failure of a firm (Khavul, Pérez-Nordtvedt, &

Wood, 2010).

In this study, we argue that a firm’s success in a foreign market

depends not only on its given portfolio of resources and

capabilities, as per the resource-based view (RBV), but also on

its capacity and ability to constantly change and adjust to

international uncertainties. Therefore, we complement RBV with

the dynamic capability view (DCV) (Kogut & Singh, 1988; Villar,

* Corresponding author: Tel.: +48 502 030 030.

E-mail addresses: cieslik@kozminski.edu.pl (J. Cieślik), ekaciak@brocku.ca

(E. Kaciak), TEK@brocku.ca (N.(. Thongpapanl).

1

Tel.: +1 905 688 5550x3902.

2

Tel.: +1 905 688 5550x5195.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.02.003

0969-5931/ß 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Alegre, & Pla-Barber, 2014). This approach offers a suitable

theoretical foundation for our research as it assumes that it is

possible for a firm to not merely respond to external challenges but

also to learn, integrate, build and actively reconfigure its internal

and external competencies (Prange & Verdier, 2011). Not only does

this approach take into consideration the relationships between

the external environment and the firm, but other factors that may

also have an impact on a firm’s strategy formulation and

performance in a global setting, such as an entrepreneurial vision,

managers’ international experience and alertness to opportunities,

can also be considered (Crick, 2009).

We use export experience and market scope strategies to

measure a firm’s engagement with the internationalization process

and propose that export experience and performance have an

inverted S-shaped relationship. Using Poland as an example, we

also seek to describe the internationalization process of firms

operating in an emerging economy. What makes this study distinct

from similar studies of firms operating in emerging economies is

that it takes into account the context of the sudden, albeit

anticipated, opportunities that were made available to Polish firms

through easier access to the vast European Union (EU) market. Our

study also offers important insights into the role of internationalization expansions during transition periods. We examine data

from 2003 to 2010, covering the year leading up to and the six-year

period following Poland’s 2004 accession to the EU. We assume

that Polish firms had already taken the scheduled 2004 accession

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

into account in their strategic orientations in 2003 (or even earlier)

and that their behavior during the year 2003 is very similar to the

subsequent years. The now available EU funds created a favorable

environment for the general economic development of Polish firms

and, thanks to the unrestricted access to the EU countries, for the

improvement of export conditions. Consequently, the export

diversification opportunities for Polish firms increased dramatically during this timeframe. No doubt, most of these firms were

exporters before the EU accession; however, without the benefits

of the EU membership, their export activities during the years

2003 to 2010 would most likely have followed the pathways

proposed by the traditional theory of internationalization and have

continued to develop rather slowly and gradually (Johanson &

Vahlne, 1977).

Although time is an important dimension of the entrepreneurship process, the extant international business research is

characterized by static, cross-sectional studies (Coviello & Jones,

2004). The snapshot nature of cross-sectional studies limits their

ability to examine how internationalization processes unfold (De

Clercq, Sapienza, Yavuz, & Zhou, 2012). Kuivalainen, Saarenketo,

and Puumalainen (2012) pointed to a need for longitudinal studies

with large samples to further examine the pattern and speed of

internationalization. Similar calls have come from other scholars

with the objective of resolving the contradictory results found by

various researchers in the field over the past several decades

(Casillas, Moreno, & Acedo, 2012). Observing a firm before and after

its first international sale may help explain the nature of the

changes that a firm faces during the internationalization process

and the performance consequences of these changes (Kuivalainen

et al., 2012). In this study, we adopt a dynamic and time-related

approach and base our analysis, which is grounded in the dynamic

capability-based view, on longitudinal data.

To examine the impact of internationalization experience and

market scope strategy on a Polish firm’s export performance, we

have organized the study as follows. First, we present a literature

review on the relationships between export performance, experience and market scope strategies, which results in a set of research

hypotheses. A methodology section describes the data collection

process, the measures utilized and the longitudinal analysis used

on the 2003–2010 data. Then, we present and discuss the results in

reference to the country’s 2004 accession to the EU. Finally, we

draw conclusions, discuss the limitations of the study and reveal

the theoretical and practical importance of our findings to scholars,

practitioners and governments of other emerging economies that

are considering joining similar trade organizations/agreements.

2. Theoretical framework and hypotheses

There is a considerable amount of empirical evidence available

on the impact of alternative market scope strategies on the export

performance of a firm. However, the results are either contradictory or inconclusive (Beleska-Spasova et al., 2012; Ruzo, Losada,

Navarro, & Diez, 2011). For example, a fundamental postulation

that describes the traditional pattern of a firm’s internationalization, known as the Uppsala model, is that internationalization is a

process in which a firm gradually increases the number and

diversity of the markets it serves (Kuivalainen et al., 2012). Thus,

the theory postulates that a firm following the traditional

internationalization pattern should have a narrow market scope

at the beginning of its international operations and, therefore, the

market concentration strategy should be the preferred option.

However, research has shown that some firms undertake a

contradictory approach to internationalization. In contrast to the

pattern of the Uppsala model, born global (BG) companies begin to

operate in multiple countries almost from inception (e.g., Loane,

Bell, & Cunningham, 2014; Oviatt & McDougall, 1994), and their

773

favorable export strategy should be market spreading. It is also

important to note that most studies that have examined the

relationships between export performance and export experience

and/or market scope strategies were primarily conducted in the

context of developed economies (Chao & Kumar, 2010; Chen & Hsu,

2010; Contractor, Kundu, & Hsu, 2003; Lee, 2010; Li, Qian, & Qian,

2012; Lin, Liu, & Cheng, 2011; Lisboa, Skarmeas, & Lages, 2013;

Mas, Nicolau, & Ruiz, 2006). In contrast, studies on emerging

market firms have been rarely undertaken (Contractor, Kumar, &

Kundu, 2007; Sahaym & Nam, 2013; Xiao, Jeong, Moon, Chung, &

Chung, 2013).

Internationalization scholars (Katsikeas and Leonidu, 1996; Lee

& Yang, 1990) highlight that exporting firms have the tendency to

either concentrate their export scopes to a smaller number of

foreign markets located closer to their home markets, to spread

their export landscapes to include a large numbers of markets, or to

do both concurrently. Morgan-Thomas and Jones (2009) find that

many firms opt to go with the concurrent entry into a larger

number of export markets at the very outset of their expansion.

This extensive international expansion is chosen, as Rialp, Rialp, &

Knight (2004) argue, not only because firms are driven to

maximize sales and market shares, but because they are also

trying to safeguard themselves against competition and optimize

their resource utilization. Datta, Rajagopalan, & Rasheed (1991),

however, assert that having a presence and operating in multiple

countries with varying cultural contexts may also burden firms

with a significant increase in transaction and operating costs,

which could potentially not be offset by the benefits of

international expansion.

The prevailing view in the literature suggests that increasing

the market scope should, at least initially, enhance a firm’s export

performance since it enables the optimization of the cost/benefit

ratio of internationalization (Chao & Kumar, 2010; Lee, 2010; Li

et al., 2012). When geographic spread is moderate, RBV indicates

that such moderate sharing of assets leads to economies of scale (Li

et al., 2012). Furthermore, firms operating in multiple countries

may be less vulnerable to individual fluctuations in market

demand and therefore may be better able to survive any market

shocks. Firms with more international experience are also likely to

have better knowledge of foreign conditions than firms with less

international experience and, as a result, are much better at

positioning their firms strategically in response to the various

international conditions and in preparation for further international expansion opportunities (Barkema & Shvyrkov, 2007).

When Poland joined the EU, the first phase in the rapid and

frequently chaotic increase of the Polish firms’ export potential

was similarly characterized by a market spreading approach.

Thanks to the newly accessible export markets, the firms began to

enjoy higher export sales due to the sheer volume of transactions

scattered throughout multiple countries. This stage is equivalent to

Stage 2, the ‘‘mid-stage internationalizers,’’ in the three-stage

S-shaped model of international expansion proposed by Contractor

et al. (2003). Polish companies did not have to go through Stage 1 of

the aforementioned model, the stage associated with ‘‘early

internationalizers.’’ As a member of the EU, they also did not face

the liability of foreignness, as early internationalizers would

normally face, and did not have to endure the additional burden

or costs associated with this liability. Given that Polish firms have

already been engaging in export activities prior to joining the EU, it

is reasonable to assume that they have, to some extent, already

acquired the needed export resources and capabilities. Nonetheless, these resources and capabilities may have been underutilized

due to the limited opportunities for internationalization available

to Polish firms. In this early, post-EU entry phase, Polish firms were

likely to realize their market spreading strategy through familiar

and neighboring markets, as the firms used and stretched their

774

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

resources and capabilities to take advantage of the easily accessible

opportunities for growth (Chao & Kumar, 2010; McDougall, Shane,

& Oviatt, 1994).

However, a firm’s rapid increase of export potential might result

in a shallow penetration into each market and the possibility of a

subsequent decline in export performance since their limited

marketing budget would have to serve a larger number of markets

(Ruzo et al., 2011). When firms use up their slack resources and

exhaust their capabilities during this post-entry phase, they cannot

continue on their positive international growth and expansion

paths until they replenish these resources and renew these

capabilities. This stage matches Stage 3 in Contractor’s et al. (2003)

model that depicts ‘‘highly internationalized firms.’’ This initial

growth followed by a subsequent decline is also conceptually

similar to the exploitative process of internationalization, which,

based on the application of existing knowledge by a firm, closely

follows the traditional incremental approach to internationalization (Kahiya & Dean, 2014; Lisboa et al., 2013; March, 1991; Prange

& Verdier, 2011; Villar et al., 2014). When the exploitative

internationalizing firm develops its knowledge based on past

experiences rather than on new capabilities, it unwittingly

restricts its ability to explore new feasible paths for export growth.

Following the volatile phase of temporary growth and the

subsequent decline of export performance, surviving firms will use

their newly acquired experience to start moving to the next phase

of market expansion. During this later post-entry phase, firms

recognize the limit of their home-country-derived capabilities as

they explore and develop host-country specific knowledge (March,

1991). As a result, firms enter a period where they accumulate new

resources, acquire fresh knowledge, learn different routines and

business practices, as well as build and annex different capabilities,

in order to get back on the path of positive growth and expansion

after the period of contraction. This is analogous to the explorative

phase of internationalization (Kahiya & Dean, 2014; Lisboa et al.,

2013; March, 1991; Prange & Verdier, 2011; Villar et al., 2014),

when a firm is able to expand thanks to the new resources and

capabilities that are strategically acquired for their chosen export

market opportunities. During this market exploration stage, the

firm’s export performance will stop deteriorating and may slowly

start improving again.

Thus, the internationalization process of firms exporting from

Poland encompasses three phases:

(1) a phase of a rapid, frequently chaotic and euphoric increase in

exporting activities in many countries;

(2) a phase of a subsequent decline in export performance; and

(3) a phase of a gradual optimization of market spreading efforts

by new learning and experience, thus leading to an improved

and more stable market performance.

These three phases of internationalization can also be found in

Lee (2010), although in that study the phases are found within the

framework of the relationship between firm performance and the

degree of internationalization (foreign sales to total sales ratio;

FSTS), rather than export experience or market spreading strategy.

Lee (2010) shows that the performance of internationalized new

ventures will first be higher, when the level of their internationalization starts increasing (Phase 1), and then lower, when the firm

starts experiencing increased transaction costs (Phase 2). In Phase

3, the firm will start accumulating business experience in its

expanded foreign markets and will again start improving its

performance. Additionally, Lee (2010) showed the existence of a

fourth phase, in which the increased costs from the liability of

foreignness outweigh the additional benefits from further international expansion. In essence, Lee’s (2010) model of the

relationship between internationalization and performance is an

M-shaped curve. Our proposed three-phase model corresponds to

the first three sections of the M-shaped curve and therefore our

model forms an inverted S-shape. The inverted S-shaped

relationship between firm performance and the degree of

internationalization was also found (albeit only for capitalintensive sectors) by Contractor et al. (2003). Chao and Kumar

(2010) as well as Li et al. (2012) performed similar tests for the

existence of the inverted S-shaped curve; however, they were

unable to obtain a significant cubic term of the geographic spread

variable. The S-shaped (not inverted) relationship between a firm’s

internationalization and its performance was confirmed by

Contractor et al. (2003) for knowledge-based sectors, by Lu and

Beamish (2004) and Xiao et al. (2013). The S-shaped relationship

has also been tested by Chen and Hsu (2010) and Lin et al. (2011),

both of whom found insignificant results. In fact, Chen and Hsu

(2010) obtained an unexpected opposite result, the inverted Ushape, which they suggested could represent the second and third

stages of Contractor’s et al. (2003) model. However, we also note

that the inverted U-shape encompasses the first two sub-stages of

the inverted S-shape, which supports the three-stage model

hypothesized in this paper. An inverted U-shaped relationship

between internationalization and performance was also confirmed

by Hitt, Hoskisson, and Kim (1997), Chao and Kumar (2010), Li et al.

(2012), and Chen, Jiang, Wang, and Hsu (2014). Table 1 presents a

summary of studies that have considered the relationships

between export performance, export experience and/or market

scope strategies.

In accordance with these arguments, we propose that:

H1. Export experience and performance have an inverted Sshaped relationship: performance is increasing at both low and

high levels of experience but it decreases at moderate levels of

experience.

H2. The growth of the number of export countries and export

performance have an inverted S-shaped relationship: performance

is increasing at both low and high levels of market spreading but it

decreases at moderate levels of market spreading.

Results reported in the literature on market concentration

activities are at best inconclusive or insignificant in this regard

(Mas et al., 2006). While there is ample research investigating

which of the two strategies, market spreading or market

concentration, actually leads to better export performance, the

results are mixed. Certainly superiority of the market spreading

strategy over the market concentration strategy has been found in

many studies (Beleska-Spasova et al., 2012; Casey & Hamilton,

2014; Cieślik, Kaciak, & Welsh, 2012; Kahiya & Dean, 2014; Khavul

et al., 2010). However, there is also a substantial body of research

which claims that it is unclear which of the two strategies leads to

the best results (Mas et al., 2006; Ruzo et al., 2011). In view of this

lack of evidence regarding the possible increased performance

benefits from the market concentration approach, we propose that:

H3. No relation exists between the growth of the share of the main

export market and export performance during any phase of the

firm’s internationalization process.

3. Methods

3.1. Sample

Our research was based on panel data (2003–2010) that can be

found in the database of Polish commodity exporters maintained

by the Analytical Centre of Customs Administration (CAAC), a

Polish Government Institution. The dataset used in the analyses

described henceforth is the result of the compilation of the

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

775

Table 1

Relationships between export performance, experience and/or market scope strategies.

Study

Empirical setting

Export

performance

(dependent

variable)

Export experience and/or market scope

strategies (independent variables)

Shape of the relationship

This current study

321 Polish firms;

longitudinal study

(2003–2010)

Export sales growth

Time after internationalization (tai);

the number of export markets growth;

the major exporter’s share growth

Chao and Kumar (2010)

Fortune Magazine

Global 500 firms;

cross-sectional study

(2004)

224 Taiwanese firms;

longitudinal study

(2000–2005)

685 Chinese firms;

longitudinal study

(2008–2011)

103 world’s largest

service firms

Return on assets

(ROA)

A composite index based on the

number of foreign subsidiaries and the

number of countries in which they

operate

The total number of foreign countries in

which the firm had subsidiaries in a

given year

The foreign sales to total sales ratio

(FSTS)

The inverted S-shape (for tai) The

inverted U-shape (for the number of

export markets growth; the inverted Sshape hypothesized as well but not

confirmed) No relationship for the

major exporter’s share growth

The inverted U-shape (the inverted Sshape hypothesized as well but not

confirmed)

Chen and Hsu (2010)

Chen et al. (2014)

Contractor et al. (2003)

Hitt et al. (1997)

Lee (2010)

Li et al. (2012)

295 US firms crosssectional study

(1989)

2236 Korean firms

cross-sectional study

(2002)

278 US firms;

longitudinal study

(2003–2009)

Earnings before

interest and taxes

(EBIT)

ROA

Return on sales

(ROS); ROA

ROA

Return on equity

(ROE); ROA

ROA; ROS

Lin et al. (2011)

179 Taiwanese firms;

longitudinal study

(2000–2005)

ROA

Lu and Beamish (2004)

1489 Japanese firms;

longitudinal study

(1986–1997)

Xiao et al. (2013)

114,398 Chinese

firms; longitudinal

study (2001–2007)

ROA; the market

value of assets

divided by the

replacement value

of assets (Tobin’s Q)

ROA; ROS

customs data on commodity exports (provided by the Customs

Office) with economic and financial data (filed in the National

Corporate Registry). Unfortunately, Polish companies sometimes

delay their financial submissions, and, therefore, only a limited

number of more recent financial statements were available. The

last year with complete coverage was 2010.

The 321 companies identified and selected for this study’s

research purposes were domestic firms based in the centrally

located Mazovia region that engaged in export sales every year

during the 2003–2010 period and had manufacturing as their core

activity (NACE 2 10–33). It is worth noting that the Eurostat data on

GDP in European regions shows that in 2009 Mazovia reached a

GDP level of EUR 22,800. This GDP level was 91% of the EU average

and a level 15 percentage points higher than the region’s pre-2004

GDP. We followed a recommendation from Freixanet (2012) and

confined our analysis to a single region, rather than to the entire

country, because of possible variations in the internationalization

processes that may be present among the other, less advanced,

regions of Poland. A similar approach was taken by Xiao et al.

(2013) when they neutralized the location effect on international

strategy and firm performance by limiting their sample to one of

the most rapidly developing areas in China: the Yangtze River Delta

A composite index based on the FSTS,

the foreign employees to total

employees ratio, and the number of

foreign offices to the number of total

offices ratio

A composite index based on the foreign

sales attributed to the market and the

weight given to each market

FSTS

The number of foreign markets served

by the firm; A composite index based

on the foreign sales attributed to the

market and the weight given to each

market

A composite index based on the FSTS,

the foreign assets to total assets ratio,

and the number of countries in which

the firm has subsidiaries

The number of the firm’s foreign

subsidiaries in each year; the number of

countries in which the firm had foreign

subsidiaries in a given year

The export sales to total sales ratio

(ESTS)

The inverted U-shape (the S-shape

hypothesized as well but not

confirmed)

The inverted U-shape

The inverted S-shape (for capitalintensive sectors) The S-shape (for

knowledge-based sectors)

The inverted U-shape (for moderate

diversifiers)

The M-shape

The inverted U-shape (the inverted Sshape hypothesized as well but not

confirmed)

The S-shape and U-shape tested but not

confirmed

The S-shape

The S-shape

region. We included only the firms that have export sales every

year during the 2003–2010 period to ensure that these firms were

committed to expanding their international operations and that

internationalization was not meant to be sporadic (Kuivalainen

et al., 2012). We excluded foreign subsidiaries from our study as

they are part of a bigger network and are likely to have or could

access considerable critical resources (e.g., foreign market

knowledge, financing) that would typically be unavailable to

and potentially irrelevant (e.g., global production rationalization)

for local Polish firms.

Of the 4850 companies in Mazovia contained in the database of

Polish commodity exporters maintained by the CAAC, only

321 companies (or approximately 6.6%) met the above criteria

and have all the economic and financial data needed for the

purposes of our study. The CAAC database contains only information about exports and imports, which we matched with other

sources such as the official company register (REGON) and

economic and financial data provided by professional suppliers.

We also attempted to obtain data on turnover, employment and

assets. It was possible to obtain the data for only 298 exporting firms

and only for the period of 2007–2010. We supplemented the base

dataset of regular exporters in 2003–2010 with this additional data.

776

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

3.2. Variable definition

3.2.1. Dependent variable

In line with the objectives of the study, our dependent variable

is export performance, namely export sales growth (expgr),

calculated as relative ratios (in terms of percentages) of export

sales (exp) in two consecutive years, i.e., [exp(t) exp(t 1)]/

exp(t 1). Export sales growth has also been used in a number of

other studies (Cieślik, Kaciak, & Welsh, 2010; De Jong & van

Houten, 2014; Ruzo et al., 2011; Sleuwaegen & Onkelinx, 2014).

Due to its skewed distribution, we transformed that variable by

using its logarithm (log_expgr).

3.2.2. Independent variables

We operationalized the market spreading activities by basing it

on the number of countries to which a firm was exporting its

product(s) in a given year (country). We calculated the relative

ratios (countrygr; in terms of percentages) of country in two

consecutive years, i.e., [country(t) country(t 1)]/country(t 1).

Due to its skewed distribution, we transformed that variable by

using its logarithm (log_countrygr). The number of export countries

is a very popular indicator of the market spreading activities and

strategy (Gallego & Casillas, 2014; Hilmersson, 2014; Kuivalainen

et al., 2012; Mas et al., 2006).

We defined the market concentration activities in a similar way.

Each firm’s export sales as channeled to its largest export market

were provided in the original CAAC dataset as a percentage of the

firm’s total export sales in a given year (prcmjrexp). We calculated

relative ratios (prcmjrexpgr) in terms of percentages of prcmjrexp in

two consecutive years, i.e., [prcmjrexp(t) prcmjrexp(t 1)]/

prcmjrexp(t 1). Due to its skewed distribution, we transformed

that variable by using its logarithm (log_prcmjrexpgr). The share of

the key export market to total export sales is a frequently used

measure of market concentration activities and strategy (MorganThomas & Jones, 2009).

As we have already emphasized, the time after internationalization (tai) is an important component in international entrepreneurship/business research because it determines, among

other things, a firm’s export experience (Mas et al., 2006; Wu &

Chen, 2014). We operationalized this variable as the difference

between the firm’s age and the time it took to embark on

internationalization (tti), which is a well-established variable in

internationalization research.

3.2.3. Control variables

We controlled for firm size (operationalized as the logarithm of

employment; De Jong & van Houten, 2014; log_empl), time to

internationalization (Gallego & Casillas, 2014; Suh & Kim, 2014;

log_tti), as well as for manufacturing industry technology levels

(Casey & Hamilton, 2014; OECD, 2005). We combined high and

medium-high technology levels into one category as we had

identified a rather small number of firms in each of these two

categories (mfct_ht_mht) followed by medium-low (mfct_mlt) and

low-technology dummies (mfct_lt; the reference category).

3.3. Model selection

To find empirical support for our hypotheses, we tested the

relationships between export performance, export experience and

the market scope strategies. We used the panel data technique

because the data-set in this study has both a time series and a

cross-sectional dimension. As a firm’s behavior may have dynamic

characteristics which cannot be explained by static panel models,

we used dynamic models in which lagged dependent and

independent variables are used as explanatory variables (Franco,

2013; Li et al., 2012).

First, we determined the order of lags for the dependent

variable. Specifically, we compared the mean square error of the

model with the first-order lagged dependent variable with that of

the second- and third-order lagged models. The results indicated

that there was no difference between them. Thus, we assumed that

the use of only the first-order lagged dependent variable is

appropriate as its coefficient fully reflects all past information

synthetically (Qian, Li, Li, & Qian, 2008). Second, to account for a

possible relationship between the strategy chosen and future

export performance, we lagged the market strategy variables by

four years. Finally, as the reverse relationship that runs from

exports to the market scope strategy-related variables may still

exist despite the use of a lag structure in these variables, we dealt

with this endogeneity by using the generalized method of

moments (GMM). The GMM estimator takes into account

problems that arise when estimating the model with endogenous

variables (Yi, Wang, & Kafouros, 2013). Thus, the following model

was applied for estimation:

log expgr it ¼ a þ b1 log expgr i;t1 þ b2 log em plit þ b3 log ttiit

þ b4 tlt þ b5 taiit þ b6 tai2it þ b7 tai3it

þ b8 log prcm jrexpgr i;t p þ b9 log countrygr i;t p þ hi

þ eit ;

p

¼ 0; 1; 2; 3; 4

where expgrit represents export performance for firm i (i = 1,

2,. . .,321) at time t (t = 1, 2,. . .,8); the next three variables control

for firm size (emplit), time to internationalization (ttiit), and

technology level (dummies tlt); taiit represents time after

internationalization; prcmjrexpgri,t-p captures a relative increase

from year (t 1) to year (t) in the percentage of the ith firm export

sales channeled to its largest export market in a given year, lagged

p years; similarly, countrygri,t-p depicts a relative increase from year

(t 1) to year (t) in the number of countries to which a firm i was

exporting its product(s) in a given year, lagged p years; hi are the

panel-level effects (which may be correlated with the covariates)

and eit are the unobserved error terms of the ith cross-sectional

unit. Since there were no significant events in Poland during the

period of study beyond joining the EU, we did not include any year

dummies in our model.

The endogeneity caused by the lagged market strategy variables

and the lagged export performance is addressed using system

GMM (sys-GMM). Arellano and Bond (1991) and Blundell and Bond

(1998) have suggested that an application of the sys-GMM

estimators is a more appropriate and efficient approach to dealing

with dynamic panel data than using the diff-GMM estimators.

Furthermore, the sys-GMM is designed for datasets with many

panels and few periods, as in our case. We found robust standard

errors to correct for possible heteroscedasticity.

4. Results

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for, and very low pairwise correlations among, the variables used in this study. An

additional regression diagnosis conducted using the varianceinflating factor (VIF) to determine the existence of multicollinearity among the variables further confirmed that multicollinearity is

not a major concern in this study: all VIFs were below 1.5

(Cenfetelli & Bassellier, 2009).

The sys-GMM estimation results are reported in Table 3. We

tested our hypotheses using four regression models. Model 1 is the

base model that includes the effects of all of the control variables

on export performance. Models 2–4 test the hypothesized inverted

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

777

Table 2

Descriptive statistics and correlationsa for the variables.

Variables

N

Mean

S.D.

Min.

Max

1

2

3

4

5

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

2247

881

1848

2247

2247

2568

0.0253

4.7445

0.8545

0.0118

0.0142

9.8146

0.5805

1.2210

0.8607

0.3018

0.4423

3.8339

5.7267

0.6934

0

1.4271

3.0445

0

3.9354

9.1901

2.9957

2.0176

1.7918

17

0.1265b

0.0075

0.1359b

0.3964b

0.1083b

0.0531

0.0603

0.0766b

0.1167b

0.0199

0.0131

0.0948b

0.3514b

0.0404

0.0758b

log_expgr

log_empl

log_tti

log_prcmjrexpgr

log_countrygr

tai

Where: expgr (export sales growth, i.e., export performance) = [exp(t) exp(t 1)]/exp(t 1), empl (employment, i.e., firm size), tti (time to internationalization), prcmjrexpgr

(major exporter’s share growth) = [prcmjrexp(t) prcmjrexp(t 1)]/prcmjrexp(t 1), countrygr (number of export markets growth) = [country(t) country(t 1)]/

country(t 1), tai (time after internationalization, i.e., export experience) = firm’s age tti.

a

For metric variables only.

b

Indicates significance at 5% level.

S-shape relationship between export experience (tai) and export

performance (H1). Additionally, Model 3 complements this

connection with the market spreading activities, represented in

this study by the growth of the number of export countries (H2)

while Model 4 does so with the market concentration activities,

represented by the growth of the share of main export market (H3).

The GMM estimator uses instrumental variables to estimate

parameters, which had to be tested for validity. As shown in

Table 3, the p-values of the Sargan test of over-identifying

restrictions for Models 3 and 4 are larger than the 0.05 level,

which suggests that the null hypothesis cannot be rejected and

that the instrumental variables chosen in the models are valid (Li

et al., 2012). The p-values of the first or second-order serial

correlation test for the four models are also larger than the

0.05 level, thus indicating that the error term is not first or secondorder serially correlated. Wald Chi-square p-values are below 0.05

(and below 0.10 for Model 2), which indicates that these models

are statistically significant. The results from Model 1 show that

none of the control variables have a significant regression

coefficient, and thus they exert minimal influence.

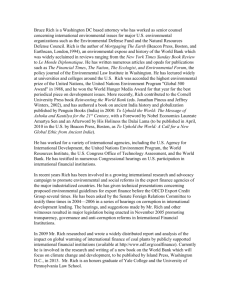

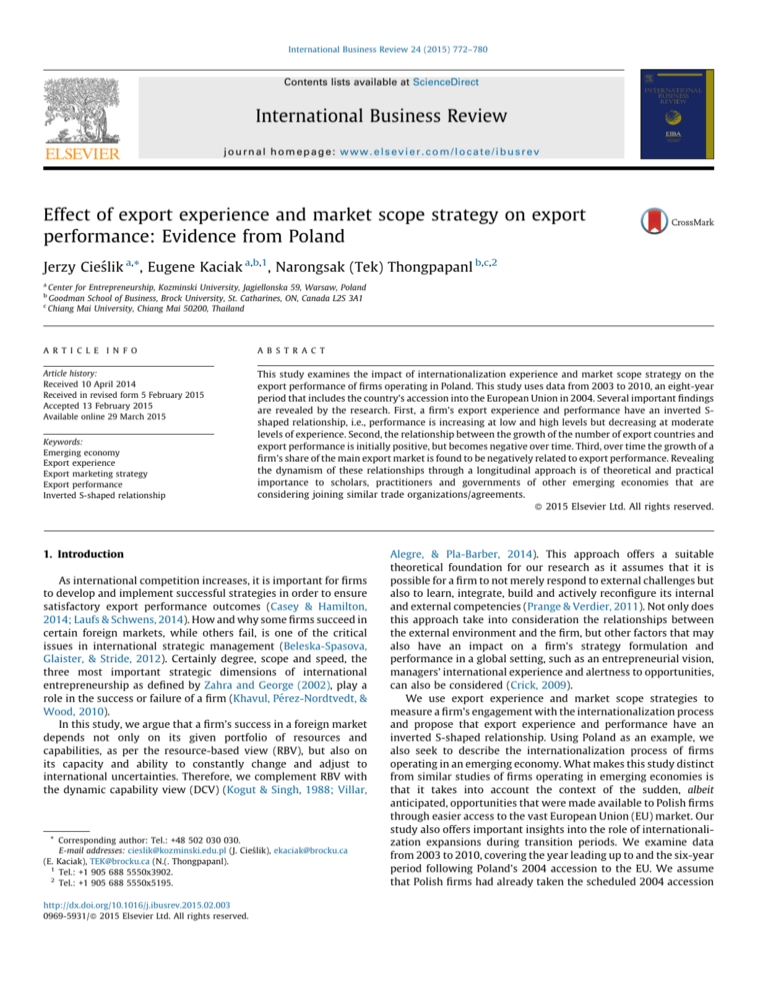

Our first hypothesis (H1) proposes that export experience and

export performance have an inverted S-shaped relationship, with

performance increasing at low and high levels of experience but

decreasing at moderate levels of experience. We test this in Models

2, 3 and 4, where time after internationalization (tai) is introduced

in its linear, quadratic and cubed forms. The final results suggest

that H1 is supported as the three regression coefficients are

significant and they have appropriate signs for an inverted S-shape

– a positive for the linear term, a negative for the squared term and

a positive for the cubed term.

To further examine how export experience influences export

performance, we left the effects of the other independent variables

unchanged and took a partial derivative of the dependent variable

based on the coefficients obtained using Model 4 in Table 3. This

Table 3

Regression of export performance on the individual variables of market scope strategy and international experience.

Independent variables

Model 1

Model 2

Model 3

Model 4

Constant

Export performance (t 1)

Firm size (log_empl)

Time to internationalization (log_tti)

Technological intensity dummies

Export experience (time after internationalization; tai)

tai squared

tai cubed

No. of export markets growth (log_countrygr) – (t)

L1 (t 1)

L2 (t 2)

L3 (t 3)

L4 (t 4)

Major exporter’s share growth (log_prcmjrexpgr) – (t)

L1 (t 1)

L2 (t 2)

L3 (t 3)

L4 (t 4)

Wald Chi-square

p-value

Sargan test of over-identifying restrictions

Chi-square

p-value

Arellano-Bond test for zero autocorrelation

in first-differenced errors (p-values)

Order 1

Order 2

No. of instruments

No. of groups

No. of observations

2.2512 (2.8347)

0.1792*** (0.0680)

0.2258 (0.4162)

0.9331 (1.0067)

Yes

0.2660 (3.5137)

0.1933*** (0.0708)

0.2875 (0.4891)

0.8007 (1.1668)

Yes

0.6795* (0.3788)

0.0609* (0.0348)

0.0016* (0.0009)

7.8066* (4.1246)

0.2397 (0.1595)

0.1330 (0.1986)

0.4872 (0.5277)

Yes

2.0297** (0.9319)

0.1698** (0.0765)

0.0045** (0.0020)

0.8291** (0.3912)

0.7094 (0.6629)

0.8608** (0.4268)

0.4870* (0.2681)

0.0408 (0.0946)

13.3125*** (5.1422)

0.2162* (0.1222)

0.6432 (0.5428)

0.5929 (1.5934)

Yes

2.1429** (0.8457)

0.1746** (0.0708)

0.0046** (0.0019)

Robust standard errors in parentheses (two-tailed tests).

*

Significant at 10%.

**

Significant at 5%.

***

Significant at 1%.

13.62

0.0182

13.59

0.0931

52.10

0.0000

1.3596 (0.9013)

1.0145 (1.0255)

0.8035 (0.8871)

0.5544 (0.7897)

0.3435* (0.1783)

32.86

0.0018

27.0191

0.0413

30.5829

0.0152

16.1952

0.1340

17.5251

0.0933

0.0056

0.1614

22

206

630

0.0063

0.1506

25

206

630

0.5067

–

25

201

483

0.3409

–

25

201

483

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

778

derivative turns out to be positive when the number of years after

internationalization is less than approximately 10 years or greater

than approximately 15 years. Thus, all other factors being equal,

the effect of export experience is positive during the first ten years

after the first export sale, then it becomes negative and remains

such until the firm had been operating for about 15 years on the

international markets, when it again returns to positive territory.

Fig. 1 represents this relationship graphically.

Hypothesis H2 proposes that the growth of the number of

export countries and export performance have an inverted Sshaped relationship: performance is increasing at both low and

high levels of market spreading but it decreases at moderate levels

of market spreading. The regression coefficients for the variable

log_countrygr in Model 3 are significantly positive during year t and

significantly negative for year (t 2) and year (t 3). Because we

did not find the inverted S-shaped relationship between the

growth of the number of export countries and export performance,

strictly speaking H2 is not supported. It is worth noting, however,

that our results indicate that market spreading activities and

performance have an inverted U-shaped relationship, which is the

front part of the inverted S-shaped relationship. This suggests that

H2 may be at least partially supported.

Hypothesis H3 predicts that export performance is not related

to the growth of the share of the main export market. Although for

the most part the regression coefficients for the variable

log_prcmjrexpgr in Model 4 are not significant, which suggests

that H3 appears to be at least partially supported, because the

negative coefficient for year (t 4) is statistically significant,

strictly speaking, H3 is not supported.

5. Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we have evaluated the impact of international

experience and market scope strategy on the export performance

of Polish firms during an eight-year period that includes the

country’s 2004 accession to the EU. Three important findings

emerge from our study that can offer theoretical and practical

insights to both international business scholars and practitioners.

First, similar to previous findings (Contractor et al., 2003 – for

capital intensive sectors; Lee, 2010 – based on the first three

phases of the M-shaped model), export experience and performance have an inverted S-shaped relationship, with performance

increasing at low and high levels of experience but decreasing at

moderate levels of experience. We determined that the first phase

of growth of export sales, sustained by the sheer volume of

transactions which are scattered throughout multiple countries,

may continue for about ten years. However, firms must be aware

that this growth is not typically sustainable and that during the

following period of approximately five years their export performance may decline. At the end of this second period, firms will

either have failed or survived. The outcome will be dependent on

their ability to use their new knowledge and experience to start

exploring and not merely exploiting the markets. In the case of

firms operating in Poland, our analysis shows that this next

successful phase of growth will take place about 15 years after the

firm has initiated its first export sale as a member (or soon to be

member) of the EU. Under the RBV and DCV frameworks, firms

would have used their slack resources and exhausted their

capabilities after the first phase of growth when the majority of

their deployment aims are focused toward easily obtainable export

market opportunities; however, firms cannot remain on their

positive international growth and expansion paths unless they

replenish their resources and renew their capabilities so that they

are able to address the needs of the lucrative but somewhat distant

opportunities.

Comparing the experiences of Polish firms after Poland joined

the EU with that of Spanish firms after Spain’s 1986 entry into the

EU (the two countries are of similar size and population), we note

that this event also accelerated the internationalization of Spanish

firms and produced a sizeable increase in commerce and two-way

Fig. 1. Inverted S-shaped relationship between export experience and performance (N = 321).

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

direct investment between Spain and the EU (Durán, 1999; Mas

et al., 2006). Spanish firms reached the highest degree of

multinationalization and the greatest foreign direct investments

(FDI) expansion about seven years after Spain’s accession (Durán,

1999; Mas et al., 2006). In this study, similar to Spanish firms, we

found that Polish firms reached the peak of their export

performance about ten years from their first export sale.

Second, we find that the market spreading activities are more

beneficial to exporting firms than the market concentration

activities as the concentration approach worsens the firms’ export

performance in the long run. However, the firms may not

immediately experience consistent export success with the market

spreading strategy. At the beginning, the euphoria caused by a

firm’s ability to be present in a large number of foreign markets at

once frequently comes at the expense of a shallow penetration in

each of the foreign markets, often the result of a limited marketing

budget shared among multiple markets. This may cause a

subsequent decline in the firm’s export sales. Only after having

survived this dangerous phase of market exploitation will the firm

start organizing its market spreading efforts more efficiently –

thanks to the new learning and experience that they have gained

during their initial expansion. During this initial market exploration stage, the firm’s export performance will slowly start

improving again, as they become better at adapting and aligning

their newly acquired resources and capabilities with their export

market landscapes (Lisboa et al., 2013; March, 1991; Prange &

Verdier, 2011). These adaptation and alignment activities are

afflicted with challenges. This is suggested by the fact that we

found no support for the final ‘‘positive’’ phase of the inverted

S-shaped relationship between the growth of the number of export

countries and export performance. One can interpret this nonfinding to mean that, on average, the Polish firms in our study were

not able to recover from these initial difficulties and thus had to

withdraw from some export markets and contract their international market expansion endeavors. Additional explanations for

this non-finding could be that it might take some time for Polish

firms in our study to adapt and align their newly acquired

resources and capabilities with their export market landscapes in a

timely fashion or that it might take some time for their

ambidextrous pursuits to result in higher export performance

outcomes (Lisboa et al., 2013; March, 1991; Prange & Verdier,

2011).

Third, while we have hypothesized that there would not be a

significant positive nor negative relationship between the firms’

growth of the share of the main export market and the firms’

export performance, it is worthwhile to note that our findings

suggest that there is a negative relationship between the two

variables during the later post-entry period. This suggestion of a

negative relationship should not be disregarded, given that

previous scholars (Allen & Pantzalis, 1996; Mas et al., 2006;

Pantzalis, 2001) have also cautioned about the negative impact of

internationalization efforts that concentrate on only a few export

markets. This negative finding may be evidence that the Polish

firms in our study were becoming too dependent on their main

export market, and thus, without an adequate level of diversification of the export base (Al-Marhubi, 2000; Grossman & Helpman,

1991; Herzer & Nowak-Lehmann, 2006), they may have over time

exposed themselves to a high risk and low return internationalization condition (Sleuwaegen & Onkelinx, 2014). Arguably, eventually the Polish firms in our study might find themselves reaching

the point of saturation with their main export market, where the

firms’ resources and capabilities will no longer allow them to

exploit and extract much from their main export market due

to conditions such as intensified competition, market maturation,

limited opportunities and demand shrinkages (Dean, Mengüç, &

Myers, 2000).

779

This study’s insights should be relevant and useful to

international business and marketing managers of a country that

is about to enter into a new free-trade zone or a new trade

agreement where there will be new export opportunities to

exploit in the short-term and explore in the long-term. The

increased awareness and understanding of the three key periods

that their firms would likely pass through [i.e., (1) a phase of a

rapid and frequently chaotic and euphoric increase of exporting

activities, (2) a phase of a subsequent decline in export

performance, and (3) a phase of a gradual optimization of market

spreading efforts by new learning and experience] should help

managers in their strategic deployment of resources and

utilization of capabilities, as well as in their strategic decisions

about which markets the companies should engage with and

disengage with. Moreover, the estimated length of time that their

firms would have to spend in each of the three post-entry periods

would help further guide their management of their resources and

capabilities and allow for the optimal application of the resources

and capabilities.

There are limitations to this study. First, our sample period is

only from 2003 to 2010. Therefore, we do not know whether and

how the S-shaped curve will change over a longer time period. New

studies are needed, based on much longer time horizons, in order

to validate or refute our findings. Second, our findings are limited

to the Polish manufacturing context. We acknowledge that the

potential for learning when exporting may vary across countries. It

would be interesting to examine these relationships in different

contexts in order to be able to account for industry and/or country

specific heterogeneity. For these reasons, we are cautious about

generalizing our findings. However, these limitations notwithstanding, this study stands to contribute to our knowledge about

the effects export experience and alternative market strategies

may have on export performance.

References

Allen., L., & Pantzalis, C. (1996). Valuation of operating flexibility of multinational

corporations. Journal of International Business Studies, 28(4), 633–653.

Al-Marhubi, F. (2000). Export diversification and growth: An empirical investigation.

Applied Economics Letters, 7(9), 559–562.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo

evidence and an application to employment equations. Review of Economic Studies,

58, 277–297.

Barkema, H. G., & Shvyrkov, O. (2007). Does top management team diversity promote

or hamper foreign expansion? Strategic Management Journal, 28, 663–680.

Beleska-Spasova, E., Glaister, E. K., & Stride, C. (2012). Resource determinants of

strategy and performance: The case of British exporters. Journal of World Business,

, 635–647.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic

panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87, 115–143.

Casey, S. R., & Hamilton, R. T. (2014). Export performance of small firms from small

countries: The case of New Zealand. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 12,

254–269.

Casillas, J. C., Moreno, A. M., & Acedo, F. J. (2012). Path dependence view of export

behaviour: A relationship between static patterns and dynamic configurations.

International Business Review, 21, 465–479.

Cenfetelli, R. T., & Bassellier, G. (2009). Interpretation of formative measurement in

information systems research. MIS Quarterly, 33(4), 689–708.

Chao, M. C.-H., & Kumar, V. (2010). The impact of institutional distance on the

international diversity–performance relationship. Journal of World Business, 45,

93–103.

Chen, H., & Hsu, W. C. (2010). Internationalization, resource allocation and firm

performance. Industrial Marketing Management, 39, 1103–1110.

Chen, Y., Jiang, Y., Wang, C., & Hsu, W. C. (2014). How do resources and diversification

strategy explain the performance consequences of internationalization? Management Decision, 52(5), 897–915.

Cieślik, J., Kaciak, E., & Welsh, D. (2010). The effect of early internationalization on

survival, consistency, and growth of export sales. Journal of Small Business Strategy,

21(1), 39–64.

Cieślik, J., Kaciak, E., & Welsh, D. (2012). The impact of geographic diversification on

export performance of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). Journal of

International Entrepreneurship, 10(1), 70–93.

Contractor, F. J., Kundu, S. K., & Hsu, C.-C. (2003). A three-stage theory of international

expansion: The link between multinationality and performance in the service

sector. Journal of International Business Studies, 34, 5–18.

780

J. Cieślik et al. / International Business Review 24 (2015) 772–780

Contractor, F. J., Kumar, V., & Kundu, S. K. (2007). Nature of the relationship between

international expansion and performance: The case of emerging market firms.

Journal of World Business, 42, 401–417.

Coviello, N. E., & Jones, M. V. (2004). Methodological issues in international entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, 19, 485–508.

Crick, D. (2009). The internationalisation of born global and international new venture

SMEs. International Marketing Review, 26, 453–476.

Datta, D. K., Rajagopalan, N., & Rasheed, A. M. A. (1991). Diversification and performance: Critical review and future directions. Journal of Management Studies, 28(5),

529–558.

De Clercq, D., Sapienza, H. J., Yavuz, R. I., & Zhou, L. (2012). Learning and knowledge in

early internationalization research: Past accomplishments and future directions.

Journal of Business Venturing, 27, 143–165.

De Jong, G., & van Houten, J. (2014). The impact of MNE cultural diversity on the

internationalization performance relationship: Theory and evidence from European multinational enterprises. International Business Review, 23, 313–326.

Dean, D. L., Mengüç, B., & Myers, C. P. (2000). Revising firm characteristics, strategy, and

export performance relationship: A survey of the literature and an investigation of

New Zealand small manufacturing firms. Industrial Marketing Management, 29,

461–477.

Durán, J. (1999). Multinacionales Espaňolas en Iberoamérica. Piramide, Madrid: Valor

Estratégico.

Franco, C. (2013). Exports and FDI motivations: Empirical evidence from U.S. foreign

subsidiaries. International Business Review, 22, 47–62.

Freixanet, J. (2012). Export promotion programs: Their impact on companies’ internationalization performance and competitiveness. International Business Review,

21, 1065–1086.

Gallego, A., & Casillas, J. C. (2014). Choice of markets for initial export activities:

Differences between early and late exporters. International Business Review, 23,

1021–1033.

Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth.

European Economic Review, 35(2-3), 517–526.

Herzer, D., & Nowak-Lehmann, F. (2006). What does export diversification do for

growth? An econometric analysis. Applied Economics, 38, 1825–1838.

Hilmersson, M. (2014). Small and medium-sized enterprise internationalisation strategy and performance in times of market turbulence. International Small Business

Journal, 32(4), 386–400.

Hitt, M. A., Hoskisson, R. E., & Kim, H. (1997). International diversification: The effects of

innovation and firm performance in product-diversified firms. Academy of Management Journal, 40(4), 767–798.

Johanson, J. K., & Vahlne, J. E. (1977). The internationalization process of the firm: A

model of knowledge development and increasing foreign market commitments.

Journal of International Business Studies, 8(1), 23–32.

Kahiya, E. T., & Dean, D. L. (2014). Export performance: Multiple predictors and

multiple measures approach. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics,

26(3), 378–407.

Katsikeas, C. S., & Leonidu, L. (1996). Export market expansion strategy: Differences

between market concentration and market spreading. Journal of Marketing Management, 12, 113–134.

Khavul, S., Pérez-Nordtvedt, L., & Wood, E. (2010). Organizational entrainment and

international new ventures from emerging markets. Journal of Business Venturing,

25, 104–119.

Kogut, B., & Singh, H. (1988). The effect of national culture on the choice of entry mode.

Journal of International Business Studies, 19, 411–432.

Kuivalainen, O., Saarenketo, S., & Puumalainen, K. (2012). Start-up patterns of internationalization: A framework and its application in the context of knowledgeintensive SMEs. European Management Journal, 30, 372–385.

Laufs, K., & Schwens, C. (2014). Foreign market entry mode choice of small and

medium-sized enterprises: A systematic review and future research agenda.

International Business Review, 23, 1109–1126.

Lee, I. H. (2010). The M Curve: The performance of born-regional firms from Korea.

Multinational Business Review, 18(4), 1–22.

Lee, C., & Yang, Y. S. (1990). Impact of export market expansion strategy on export

performance. International Marketing Review, 7(1), 41–51.

Li, L., Qian, G., & Qian, Z. (2012). The performance of small and medium-sized

technology-based enterprises: Do product diversity and international diversity

matter? International Business Review, 21, 941–956.

Lin, W-T., Liu, Y., & Cheng, K-Y. (2011). The internationalization and performance of a

firm: Moderating effect of a firm’s behavior. Journal of International Management,

17, 83–95.

Lisboa, A., Skarmeas, D., & Lages, C. (2013). Export market exploitation and exploration

and performance: Linear, moderated, complementary and non-linear effects.

International Marketing Review, 30(3), 211–230.

Loane, S., Bell, J., & Cunningham, I. (2014). Entrepreneurial founding team exits in

rapidly internationalising SMEs: A double-edged sword. International Business

Review, 23, 468–477.

Lu, J. W., & Beamish, P. W. (2004). International diversification and firm performance:

The S-curve hypothesis. Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 598–609.

March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87.

Mas, F. J., Nicolau, J. L., & Ruiz, F. (2006). Foreign diversification vs concentration

strategies and firm performance: Moderating effects of the market, product and

firm factors. International Marketing Review, 23(1), 54–82.

McDougall, P. P., Shane, S., & Oviatt, B. M. (1994). Explaining the formation of

international new ventures: The limits of theories from international business

research. Journal of Business Venturing, 9(6), 469–487.

Morgan-Thomas, A., & Jones, M. V. (2009). Post-entry internationalization dynamics:

Differences between SMEs in the development speed of their international sales.

International Small Business Journal, 27(1), 71–97.

OECD (2005). Oslo manual guidelines for collecting and interpreting innovation. OECD

Publications.

Oviatt, B. M., & McDougall, P. P. (1994). Toward a theory of international new ventures.

Journal of International Business Studies, 25, 45–64.

Pantzalis, C. (2001). Does location matter? An empirical analysis of geographic scope

and MNC market evaluation. Journal of International Business Studies, 32(1), 133–

155.

Prange, C., & Verdier, S. (2011). Dynamic capabilities, internationalization processes

and performance. Journal of World Business, 46, 126–133.

Qian, G., Li, L., Li, J., & Qian, Z. (2008). Regional diversification and firm performance.

Journal of International Business Studies, 39, 197–214.

Rialp, A., Rialp, J., & Knight, G. A. (2004). The phenomenon of early internationalizing

firms: What do we know after a decade of scientific inquiry (1993–2003)?

International Business Review, 14(2), 147–166.

Ruzo, E., Losada, F., Navarro, A., & Diez, J. A. (2011). Resources and international

marketing strategy in export firms: Implications for export performance. Management Research Review, 34(5), 496–518.

Sahaym, A., & Nam, D. (2013). International diversification of the emerging-market

enterprises: A multi-level examination. International Business Review, 22, 421–436.

Sleuwaegen, L., & Onkelinx, J. (2014). International commitment, post-entry growth and

survival of international new ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 29, 106–120.

Suh, Y., & Kim, M.-S. (2014). Internationally leading SMEs vs. internationalized SMEs:

Evidence of success factors from South Korea. International Business Review, 23,

115–129.

Villar, C., Alegre, J., & Pla-Barber, J. (2014). Exploring the role of knowledge management practices on exports: A dynamic capabilities view. International Business

Review, 23, 38–44.

Wu, J., & Chen, X. (2014). Home country institutional environments and foreign

expansion of emerging market firms. International Business Review, 23, 862–872.

Xiao, S. S., Jeong, I., Moon, J. J., Chung, C. C., & Chung, J. (2013). Internationalization and

performance of firms in China: Moderating effects of governance structure and the

degree of centralized control. Journal of International Management, 19, 118–137.

Yi, J., Wang, C., & Kafouros, M. (2013). The effects of innovative capabilities on

exporting: Do institutional forces matter? International Business Review, 22,

392–406.

Zahra, S. A., & George, G. (2002). International entrepreneurship: The current status of

the field and future research agenda. In M. A. Hitt, D. Ireland, D. Sexton, & M. Camp

(Eds.), Strategic entrepreneurship: Creating an integrated mindset (pp. 255–288).

Oxford: Blackwell.