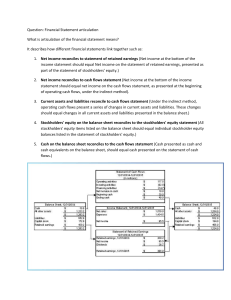

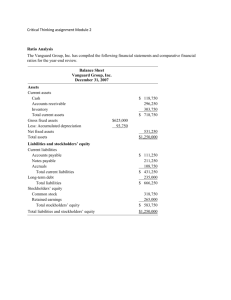

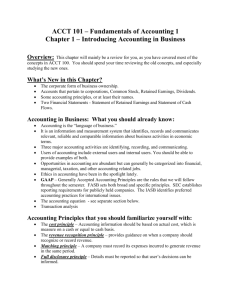

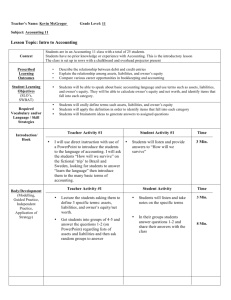

Introducing Financial Statements and Transaction Analysis

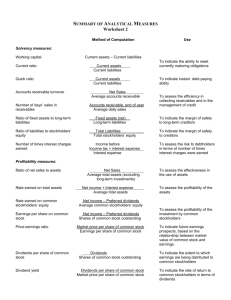

advertisement