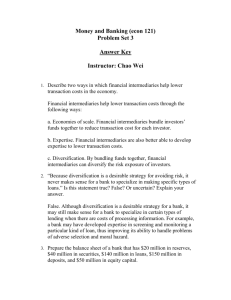

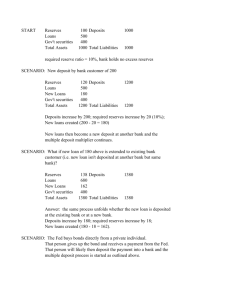

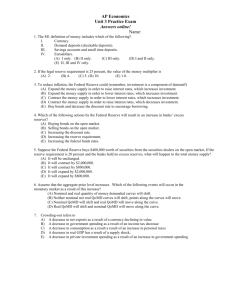

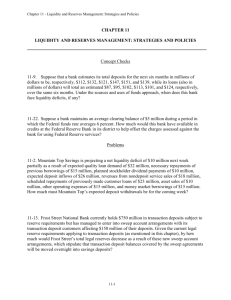

Money, the Federal Reserve, and the Interest Rate

advertisement