Market Environment, Marketing audit and Performance: Empirical

advertisement

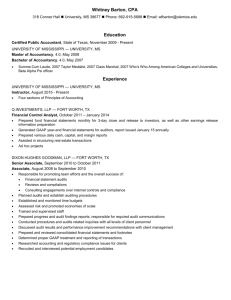

Market Environment, Marketing audit and Performance: Empirical Evidence from Taiwanese Firms Wen Kuei Wu* The purpose of this study is to develop and test a model of antecedents and consequences of marketing audit. Specially, this study appears to be one of the first papers to focus on the use and contribution of marketing audit in marketing performance of Taiwanese firms. Our empirical analysis indicates the greater the environmental munificence, the less extent of effort dedicated to audits for marketing execution (AME). The result also yields a strong support for the effects of AME on the marketing performance. The study provides managerial insights into how the implementing marketing audit can help ensure the marketing executives to have adequate information for marketing, and what extent they have the greatest effect on the marketing performance of Taiwanese firms. Field of Research: Marketing Audit, Marketing Management 1. Introduction In recent years, increasing pressure to reduce costs has forced many companies to radically reengineer the way they do business. This pressure is also leading marketing executives to reconsider the goals, structure, and effectiveness of their marketing arms. As a comprehensive review of a company’s market environment, the marketing audit identifies any inadequacies in overall marketing structures. It also identifies operational strengths and weaknesses and recommends the necessary changes to the company’s marketing strategies. If the marketing audits are done correctly, they will provide management with a useful and analytical tool for evaluating, measuring, motivating and revising management actions (Mylonakis, 2003). *Wen Kuei Wu, Chaoyang University of Technology, 168, Jifeng E. Rd., Wufeng District, Taichung, 41349 Taiwan, R.O.C. email: wenkuei@cyut.edu.tw However, the marketing audit is currently still ignored by companies and business managers due to that many market managers conceive the marketing audit as a profusion of checklists and as distraction from the current creative process that is at the heart of marketing functions (Mylonakis, 2003). The benefits of using the marketing audit and implementing its recommendations lie in perceptions of its ability to influence a change in business performance (Clark, Abela, and Ambler 2006). Thus, it is important to be clear whether and how marketing audits influence the business performance. Since the marketing audit must be considered as a comprehensive review and appraisal of the total marketing operation, it requires a systematic and impartial review of a company’s recent and current operations and its market environment (Zikmund and d’Amico, 2000). However, the scope of audit depends on the cost involved, the target markets served and its market environment (Mylonakis, 2003). It is necessary to explore how these environmental conditions influence the issues selected and the activities implemented for the marketing audit so as to have an insight into what are exactly the company’s considerations when marketing audits are implemented. Although the marketing audit has been used since its introduction to the marketing management process, there is no evidence of its empirical validation of its practice and usefulness in Taiwan. The purpose of this study is to investigate how the practice of marketing audits might be influenced by market environment characteristics, and to examine the scope of conducting marketing audit as well as what extent they have the greatest effect on performance of Taiwanese firms. 2. Background and Conceptualization 2.1 The Marketing Audit The marketing audit was described as a systematic, critical, and impartial review of the total marketing operation; of the basic objectives and policies of the operation and assumptions that underlie them; and the methods, procedures, personnel, and organization employed to implement the policies and achieve the objectives (Shuchman, 1959). Kotler et al. (1977) refined the marketing audit concept into a comprehensive, systematic, independent, and periodic examination of a company’s or SBU’s strategies, objectives, activities, 1 and environment, designed to reveal problems and opportunities, and to recommend actions that would improve the company’s marketing performance. The refined audit model identified six proposed components of the marketing audit, and advocated the use of a standard set of procedures. Kotler et al.’s six proposed marketing audit components included: (1) the market environment audit, consisting of analyses of both the macro environment and the task environment; (2) the marketing strategy audit, to assess the consistency of marketing strategy with environmental opportunities and threats; (3) the marketing organization audit, designed to assess the interactions between the marketing and the sales organization; (4) the marketing systems audit, to evaluate procedures used to obtain information, plan and control marketing operations; (5) the marketing productivity audit, assessing accounting data to determine optimal sources of profits, as well as potential cost savings; and (6) the marketing function audit, reviewing key marketing functions based primarily on prior audit findings. As we can see, the first two components—market environment audit and marketing strategy audit refer to the processes of auditing for marketing planning. The rest components concern the auditing for marketing execution. However, from conceptual and practical perspectives, the marketing audit has many significant problems including the lack of suitably qualified independent auditors (Kotler et al.,1977), gaining management cooperation from within marketing (Capella and Seckely, 1978), information availability (Rothe et al., 1997), sufficient communication with top managers to ensure access and understanding of information (Bonoma, 1985). Meanwhile, the marketing audit is also criticized for disconnecting from the overall control system (Brownlie, 1993); periodic rather than ongoing assessments of marketing performance (Kotler et al., 1977); and application with the objective of defining problems but not necessarily providing insights into solutions (Wilson, 1980). As a result, the used measurement approaches of marketing audit have been primarily qualitative checklists, with little empirical validation (Rothe et al., 1997; Morgan et al., 2002). Furthermore, there has been little research on the factors influencing implementation of marketing audits. 2 2.2Market Environment Characteristics’ Influences on Marketing Audit Hostile market environments characterized by intense competition and lack of exploitable opportunities, and dynamic market environments characterized by rapid technological advancements and rapidly changing consumer preferences, are considered to have a significant influence on business performance (Covin and Slevin 1989; Gray et al. 1998;Jaworski and Kohli 1993; Low 2000; Rust, Ambler, Carpenter, Kumar & Srivastava 2004; Slater and Narver 1994). According to structure-conduct-performance (SCP) model (Mason, 1939; Bain ,1954), market structure affects market conduct, which in turn affects marketing performance. This means that industry characteristics affect market conduct (e.g., production and pricing strategies, research and innovation, pricing behavior, advertising) because these different industry characteristics can be logically organized, analyzed and putted into considerations to improve the efficiency and effect of market conduct by skillful marketers. Clearly, the desire to be competitive in such environmental conditions may provide the impetus for organizations to implement marketing audits to ensure the marketing executives to have adequate environmental information for market conduct—planning and allocating resources properly to different markets, products, territories and marketing tools. In the literature, environment has been defined as a multidimensional concepts (Egeren and O’Connor, 1998): (1) objects external to the organization (customers, suppliers, competitors); (2) attributes of the external environment (complexity, dynamism, munificence); or (3) managerial perceptions of uncertainty. Following Egeren and O’Connor’s (1998) approach, this study will define environment in terms of marketing manager’s perceptions of the munificence and dynamism attributes. Environmental munificence refers to environmental capacity which permits organizational growth and stability. In environments low in munificence, competition increases (Dess and Beard, 1984; Porter, 1980). Dynamism is the degree of change or market stability. Overall, the reason why market environment characteristics may influence marketing audits is because marketing audits provide the marketing management with programmed appraisals and critical evaluations of the environmental analysis and help ensure the marketing management to identify opportunities and threats from markets. Thus, based on the discussion, it can be hypothesized: 3 Hypothesis 1: The greater the environmental munificence, the less extent of effort dedicated to marketing audits in terms of audits for marketing planning (H1a) and audits for marketing execution (H1b). Hypothesis 2: The greater the environmental dynamism, the greater the extent of effort dedicated to marketing audits in terms of audits for marketing planning (H2a) and audits for marketing execution (H2b) . 2.3 Marketing Audit and Business Performance A review of the various definitions of marketing audit suggest that one might expect organizations with well-implemented marketing audits to have a greater capacity to achieve their stated direct and indirect performance objectives. These objectives might include process improvement and continuous monitoring of marketing performance (Brownile, 1996), channeling efforts in optimal directions (Quelch, Farris and Oliver, 1987), gaining important findings, recommendations and sufficient knowledge of customers for improving the marketing performance (Mylonakis, 2003), strategy execution effectiveness, user satisfaction and organizational learning (Morgan et al., 2002), and change in market share and the overall financial performance (Taghian and Shaw, 2008). More recently, Taghian and Shaw(2008) have started to examine the use of marketing audits as a facility that can assist with the marketing orientation strategy, and their relationships with change in business performance. Theoretically, business performance from implementations of marketing audits could be linked into several propositions. First, the comprehensive, systematic, independent, and periodic examination of the organization’s marketing function will, potentially, lead to early detection and awareness of existing or emerging marketing issues that may influence the organization’s business performance (Brownlie 1996). Second, the marketing audit provides recommendations for corrective actions to be prepared as a balanced tactical approach for readjusting the marketing initiatives in line with the market dynamics (Kotler et al., 1977; Dafe and Macintosh, 1984; Wilson, 1992; Morgan, Clark and Gooner, 2002; Mylonakis, 2003). Furthermore, the marketing audit may change the attitude of management toward a more comprehensive awareness of the environment, a more objective and a less 4 intuitive approach in decision making, and allowing independent opinions to be expressed and be used to achieve organizational objectives (Sauter, 1999; Taghian and Shaw, 2008). Hence, it may be expected that the usage of marketing audits is related more strongly to increase marketing performance. Considering all these findings, we propose: Hypothesis 3: The greater the extent of effort dedicated to marketing audits in terms of audits for marketing planning (H3a) and audits for marketing execution (H3b), the higher the marketing performance. The six hypothesized relationships are shown in Figure 1. 3. Research Method 3.1 Measures The external market environment measures were drawn from the research undertaken by Slater and Narver (1992), Khandwalla (1977), Zahra (1996), and Baum and Wally (2003), and included perceptual measures of the munificence and dynamism attributes (Egeren and O’Connor (1998)). This research developed a three-item, seven-point semantic (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree) differential measure of munificence and a four-item, seven-point semantic differential measure of dynamism. 5 Figure 1. The conceptual model ENVIRONMENTAL MUNIFICENCE (EM) AUDITS FOR (-) (-) MARKETING (+) PLANNING (AMP) MARKETING PERFORMANCE (MP) (+) (+) (+) ENVIRONMENTAL AUDITS FOR DYNAMISM (ED) MARKETING EXECUTION (AME) The implementation of marketing audits measures were drawn from the Kotler et al.’s (1977) six proposed marketing audit dimensions. The first set of dimensions (i.e. the market environment audit and marketing strategy audit) was referring to audits for marketing planning. The rest set of dimensions measured audits for marketing execution (i.e. the marketing organization audit, system audit, productivity audit and function audit). Hence, a separate multiple-item, seven-point semantic (1 = never, 7 = frequently) scale was developed to measure each of these dimensions of marketing audit implementation. These items asked the respondent to assess how often his or her firm implements elements of the firm’s marketing audits. The marketing performance measures were drawn from the researches by Choi and Mueller (1992) and Slater and Narver (1992). Since subjective measures of organizational performance are commonly used in research, this study utilized a perceptual, multiple-item, and seven-point semantic (1 = highly dissatisfied, 7 = highly satisfied) performance measure related to relative market share, sales and profitability. Subjective performance measures were used because objective relative performance measures were virtually impossible to obtain at the business level and subjective measures have been 6 shown to be correlated to objective measures of performance (Dess and Robinson, 1984; Slater and Narver, 1994). Relative performance was used to control for performance differences due to industry differences (Hambrick and Mason, 1984). We conducted a series of pre-tests and interviews to finalize the conceptual model and the measures in the model. First, five academic experts with extensive experience and knowledge about marketing and marketing audit were asked to evaluate the adequacy of the items. Second, the revised questionnaire was pre-tested using a sample of 30 firms randomly drawn from the CommonWealth Magazine's listing of Taiwan's manufacturers and service enterprises. The senior executives responsible for marketing were asked to complete the questionnaire and to provide any concerns related to the questionnaire. 3.2 Data Collection A sample of one thousand companies was drawn from a commercially available CommonWealth Magazine's listing of Taiwan's Top 1000 Manufacturers and 500 Service Enterprises in 2009. To promote sufficient variation in organization type and organization size, the sample was comprised of 250 each of small and medium sized service and consumer goods organizations and 250 each of large consumer goods and services organizations. Following an initial mailing of the questionnaire, a follow-up phone call was done to encourage response. A total of 160 fully completed usable responses were received for an effective response rate of 16%. As suggested by Armstrong and Overton (1977), the study compared early responses with late responses. According to a t-test analysis, these two groups of respondents had no significant differences across all the key variables. In addition, this study also compared the firms that responded to survey against those that did not on three characteristics: firm sales, number of employees, and 2008 return on assets (ROA). There was no significant difference between responding and nonresponding firms on firm sales and ROA. 7 3.3 Analysis Procedures First, exploratory factor analyses (EFA) and reliability analyses were conducted to analyze items separately for each facet. Based on the results, EFA revealed two-factor solution for the external market environment measures accounted for 80.28% of the variance extracted, and revealed one-factor solution for the marketing performance measures accounted for 80.31% of the variance extracted. Therefore, the retained factors were succinctly measured by these variables. For the implementation of marketing audits, EFA yielded a two-factor solution for the first set of dimensions (i.e. audits for marketing planning) accounted for 72% of the variance extracted, corresponding closely with the hypothesized dimensions of market environment audit and marketing strategy audit. However, the results showed that 7 of 17 items were inadequate. Likewise, EFA also yielded a two factor solution for another set of dimensions (i.e. audits for marketing execution) accounted for 76% of the variance extracted, corresponding closely with the hypothesized dimensions of marketing organization audit and marketing function audit. We retained the 14 items that demonstrated acceptable loading on their hypothesized factor (>0.3) and no significant cross-loading for further analysis. We also conducted a subsequent confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to purify the measures. This measurement model produced the following fit statistics: x2 = 78.55, degrees of freedom (d.f.) = 63, GFI = 0.94, AGFI = 0.90, CFI = 0.98, NFI = 0.94, RMSEA = 0.04, PCFI = 0.68, and CMIN/DF = 1.25. Overall, the model provides a reasonable fit to the data. The composite reliability (CR) coefficients were: environmental munificence (0.81), environmental dynamism (0.82), audits for marketing planning (0.83), audits for marketing execution (0.61) and marketing performance (0.85). CR is an indication of internal consistency and conceptually similar to Cronbach’s alpha; it should exceed 0.60 for exploratory model testing (DeVellis, 1991). The descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and polychoric correlations) of the study variables are shown in Table 1. The average variance extracted in the remaining constructs was always greater than 0.50, which is indicative of convergent validity (Sarkar, Echambadi, Cavusgil and Aulakh 2001). As Table 1 shows, the squared phi coefficients between each of the pairs of constructs were less than the average variance extracted, indicating 8 discriminant validity. Overall, the results confirmed the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures used in this study. Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations of Constructs Measured Measures ED EM AMP AME MP Environmental Dynamism (ED) 0.55 Environmental Munificence (EM) 0.42 0.60 Audit for Marketing Planning (AMP) 0.20 0.34 0.71 Audit for Marketing execution (AME) 0.25 0.50 0.17 0.79 Marketing Performance (MP) 0.40 0.08 0.00 0.18 0.66 Mean 4.28 5.18 2.43 2.82 4.13 Standard Deviation 1.25 1.34 2.10 2.12 1.16 4. Results and Discussion 4.1 Effects of Market Environment on Marketing Audits The structural equation results are shown in Table 2. In support of H1a and H1b, environmental munificence (EM) was negatively associated with audits for marketing planning (AMP) (β =-0.36, p < 0.05) and audits for marketing execution (AME) (β =-0.41, p < 0.05), as we predicted. However, the expected influence of environmental dynamism (ED) on AMP and AME was not evident. H2a and H2b were not supported. Organizations must respond to low munificence and to ensure that consumers choose their service offerings over competing alternatives by developing a higher degree of market orientation (Egeren and O’Connor, 1998). The implementation of the recommendations of the marketing audit can be of benefit to enhance the market orientation strategy of an organization in achieving business performance objectives (Taghian and Shaw, 2008). It is therefore reasonable to see organizations respond to low munificence by implementing marketing audits. 9 Table 2 Structural Relationships Dependent Predictor Estimate Standard Standardized t-value Variable AMP AME MP Error R2 Estimate EM 0.45 0.11 -0.36 -2.70** ED -0.03 0.18 -0.02 -0.15 EM 0.56 0.17 -0.41 -3.32** ED -0.12 0.20 -0.08 -0.62 AMP 0.01 0.03 0.02 0.42 AME 0.11 0.05 0.20 2.25** 0.13 0.17 0.04 *P<0.1; ** p<0.05 The lack of support for the ED/AMP and ED/AME relationships could possibly be due to the limitations of marketing audit. Indeed, many organizations think the market environments are too turbulent to be predicted and thereby there is little need for systematic and impartial review of market environment. Hence, the marketing audit may be ignored because of the environmental dynamism. Another contributing factor may have been the fact that completing a marketing audit does not automatically imply that what the auditors consider to be the appropriate actions will be taken by the client—marketing manager (Brownile, 1996). 4.2 Effects of Marketing Audit on Marketing Performance As seen in the Table 2, only the path coefficient regarding the effect of AME on the marketing performance (MP) was significant. This significant path estimates indicates the implementation of AME is associated with better marketing performance (β =0.20, p < 0.05). This result offer strong support for the effects of AME on the marketing performance (i.e., H3b) and reveal the importance of effective AME on marketing performance outcomes. This result is consistent with similar findings reported by Taghian and Shaw(2008). The pursuit of marketing audits, especially audits for marketing execution, can enables management to identify contemporary marketing weaknesses or detect emerging marketing issues in implementing marketing strategies and lead to effectiveness of marketing activities. We did not find a relationship between the AMP and marketing performance. The lack of results may be due to the poor implementation of AMP within respondents. There are only approximately 30 percent of the respondents 10 indicated that they used AMP periodically. Furthermore, AME seems to be used mostly to evaluate the efficiency and effectiveness of marketing activities. This could possibly suggest that AME has more possibility than AMP to result in superior marketing performance. 5. Conclusion and Suggestions 5.1 Managerial Implications The results of this study indicate that there was a strong and significant effect indicating a positive relationship between low environmental munificence and marketing audits, suggesting that managers might pay more attention to implementing marketing audit for responding to low munificence and ensuring the marketing executives to have adequate environmental and competitive information for market conduct. For businesses that already confront with low munificence in market environment, it is highly advisable to conduct marketing audits periodically, not only to assure marketing executives of assessing the key trends and their implications for company marketing action, but also to assure the marketing strategies and activities of been proceeded righteously and completely in a manner consistent with both consumer needs and organizational goals of marketing. Our findings suggest that AME including marketing organization audit and marketing function audit is beneficial. Indeed, AME helps management to have insight into how the marketing strategies and action programs were proceeding as planned, and whether the marketing mixes were matched with market environments. Notwithstanding the insignificant force of AMP upon marketing performance, the ignorance of AMP within respondents still needs to be acknowledged. Theoretically, the usage of the AMP may assist with the more comprehensive understanding of market environment and the more sophisticated formulation of marketing strategies. However, the poor implementation of AMP shows that managers within respondents do not consider AMP as an aid to the management of a market strategy. It is worth noting that AME along is not enough; the failure to study market environments and consumer needs and ensure them have been comprehensively implemented with AMP might lead to the misunderstanding of market situations and downfall of marketing 11 performance. 5.2 Limitations and Further Research As with any study, there are limitations in the present work that need to be identified. First, although the surveys were conducted among knowledgeable marketing decision makers, the problems associated with self-reported data from mail surveys are possible and then we recognize the potential for single-informant response bias. Second, the study employed perceptual measures for all of the constructs. The outcome measures were also collected contiguously with the other construct indicators. However, analyses of the multi-item scales provided supportive evidence regarding the reliability and discriminant validity of the measures. In terms of future direction, several fruitful research areas can be offered. First, future studies might consider identifying other variables such as the process in preceding the marketing audit, the different levels of market development, and the perceived importance of marketing audit that are likely to mediate the relationships as well. Moreover, future studies could also consider the influences of marketing resources deployment and adapt the variable measures of marketing audit to fit other types of business. Finally, larger national samples would be beneficial for comparing and testing potential international differences using structural equation methods to verify these findings. Reference Armstrong, J. S., & Overton, T. S. 1977. ―Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys’, Journal of Marketing Research”, 14 (August), 396-402. Bain, J. 1954. ―Economies of Scale, Concentration, and the Condition of Entry in Twenty Manufacturing Industries’, American Economic Review”, 44(1), 15–39. Baum, J. R., & Wally, S. 2003. ―Strategic decision speed and firm performance’, Strategic Management Journal”, 24, 1107-1129. Bonoma, T.V. 1985. The marketing edge: making strategies work, New York: Free Press. Brownlie, D. 1993. ―The Marketing Audit: A Metrology of Explanation’, Marketing Intelligence and Planning”, 11 (1), 4–12. 12 Brownlie, D. 1996. ―The Conduct of Marketing Audits: A Critical Review and Commentary’, Industrial Marketing Management”, 25(1), pp.11-22. Capella, L. M., & Sekely, W. S. 1978. ―The Marketing Audit: Methods, Problems and Perspectives’, Akron Business and Economic Review”, 9 (3), 37–41. Choi, F., & Mueller, G. G. 1992. International accounting, 2th ed. New Jersey: PrenticeHall Inc. Clark, B. H., Abela, A. V., & Ambler, T. 2006. ―An Information Processing Model of Marketing Performance Measurement’, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice”, 14 (3), 191–208. Covin, J. G., & Slevin, D. P. 1989. ―Strategic Firms in Hostile and Benign Management of Small Environments’, Strategic Management Journal”, 10 (1), 75-87. Dess, G. G., & Beard, D.W. 1984. ―Dimensions of organizational task environments’, Administrative Science Quarterly”, 29, 52-73. Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R.B. 1984. ―Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: the case for the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit’, Strategic Management Journal”, 5, 265-73. DeVellis, R. F. 1991. Scale Development: Theory and Application, Sage: Newbury Park, CA. Egeren, M.V., & O’Connor, S. 1998. ―Drivers of market orientation and performance in service firms’, Journal of Services Marketing”, 12(1), 39-58 Gray, B.J., Matear, S., Boshoff, C., & Matheson, P. K. 1998. ―Developing a Better Measure of Market Orientation’, European Journal of Marketing”,, 32 (9/10), 884-903. Hambrick, D.C., & Mason, P.A. 1984. ―Upper echelons: the organization as a reflection of its top managers’, Academy of Management Review”, 9( 2), 193-206. Jaworski, B., & Kohil, A. K. 1993. ―Market Orientation: Antecedents Consequences’, Journal of Marketing”, 57 (July), 53–70. and Khandwalla, P. N. 1977. The Design of Organizations, Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, New York, NY. Kotler, P., Gregor, W., & Rodgers, W. 1977. ―The Marketing Audit Comes of Age’, Sloan Management Review”, 18 (Winter), 25–44. Low, G. S. 2000. ―Correlates of Integrated Marketing Communications’, Journal of Advertising Research”, 40 (3), 27-39. Mason, E. 1939. ―Price and Production Policies of Large-Scale Enterprise’, American Economic Review”, 29(1), 61–74. 13 Morgan, N. A., Clark, B. H., & Gooner, R. 2002. ―Marketing productivity, marketing audits, and system for marketing performance assessment: Integrating multiple perspectives’, Journal of Business Research”, 55, 363-375. Mylonakis, J. 2003. ―Functions and responsibilities of marketing auditors in measuring organizational performance’, International Journal of Technology Management”, 25(8), 814-825. Porter, M. 1980. Competitive Strategy. Free Press, New York, NY. Quelch, J.A., Farris, P.W., & Oliver, J.M. 1987. ―The Product Management Audit’, Harvard Business Review”, 65 (March-April), 30-36. Rothe, J.T., Harvey, M. G., & Jackson, C. E. 1997. ―The Marketing Audit: Five Decades Later’, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice”, 5 (3), 1-16. Rust, R.T., Ambler, T., Carpenter, G. S., Kumar, V., & Srivastava, R. K. 2004. ―Measuring Marketing Productivity: Current Knowledge and Directions’, Journal of Marketing”, 68 (October), 76-89. Future Sarkar, M. B., Echambadi, R., Cavusgil, S. T., & Aulakh, P. S. 2001. ―The Influence of Complementarity, Compatibility, and Relationship Capital on Alliance Performance’, Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science”, 29 (4), 358-373. Sauter, V. L. 1999. ―Intuitive Decision-Making’, Communications of the ACM”, 42 (6), 109–115. Shuchman, A. 1959. ―The marketing audit: its nature, purposes and problems‖, In Garden, A. N. and Bailey, E. R. (Ed.), Analyzing and improving marketing performance: marketing audits in Theory and practice, New York: American Management Association, pp.11-19. Slater, S. F., & Narver, J.C. 1992. Market Orientation, Performance, and the Moderating Influence of Competitive Environment, Report No. 92-118, Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge, MA. Slater, S. F., & Narver, J. C. 1994. ―Does Competitive Environment Moderate the Market Orientation–Performance Relationship’, Journal of Marketing”, 58 (January), 46–55. Taghian, M., & Shaw, R. N. 2008. ―The Marketing Audit and Organizational Performance: An Empirical Profiling’, Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice”, 16(4), 341-349. Wilson, M. 1980. The management of marketing, Westmead, England: Gower. Wilson, A. 1992. Aubrey Wilson’s Marketing Audit Checklists: A Guide to Effective Marketing Resource Realization, 2th ed., McGraw Hill, London. 14 Zahra, S. A. 1996. ―Technology Strategy and Financial Performance: Examine the Moderating Role of the Firm’s Competitive Environment’, Journal of Business Venturing”, 11, 189-219. Zikmund, W., & d’Amico, M. 2000. The power of e-marketing, SouthWestern, 7th edition. 15