An Integrated Unit on The Aztecs and The Mayans

advertisement

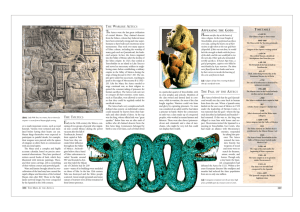

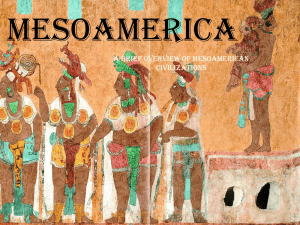

AN INTEGRATED UNIT ON THE AZTECS AND THE MAYAS CARMEN KUCZMA MARILU ADAMSON WITH ASSISTANCE FROM PAT CLARKE AND THE B.C. GLOBAL EDUCATION PROJECT AND SANDRA MORÁN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank: TIME Inc. for their permission to reprint excerpts from Secrets of the Maya (August 9,1993). Curbstone Press and Victor Montejo for permission to reprint “The Bird Who Cleans the World”, “He Who Cuts the Trees Cuts His Own Life” and “Laziness Should Not Rule Us” from The Bird Who Cleans the World and Other Mayan Fables. The Union of Guatemalan Education Workers (STEG) for permission to reprint the Itzaj Mayan words from the article “La Educación Popular”. Photos by Carmen Kuczma Cover Graphic: Amrit Baidwan This material is covered by copyright and may not be used for commercial purposes. The author of this material has provided it for use by students and teachers in instructional settings in public schools. Users of this material should respect that intent and should acknowledge the author. Copies available from: Lesson Aids B.C. Teachers’ Federation 100-550 West 6th Avenue Vancouver, BC V5Z 4P2 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Elements of Global Education 4 Key Understandings 6 Maps: North America Central America Aztec and Mayan areas 8 A. B. C. The Mayas 9 The Aztecs 10 Food 12 Food and Cooking Activities 13 Recipes 15 Spelling Words and Activities 18 Literature: Aztec Legends Mayan Stories 20 20 26 Writing Activities 30 Aztec Poetry 32 Mayan Poetry 33 Poetry Activities 34 Poetry Writing Examples of Poetry Models 35 35 Math Activities 37 Science Activities 38 Map – Mesoamerican Societies 40 Social Studies Activities 41 Art Activities 45 Extension Activities Prophecy Sacrifice Mayan Beauty Secrets 49 55 57 59 Miscellaneous 60 Pronunciation 63 Bibliography 64 Appendices 66 2 Stela at Copán INTRODUCTION T he following unit has been developed for teachers who wish to integrate the study of the Aztecs and/or the Mayas into other curriculum areas. Teachers will have opportunities for integration through a variety of activities. Ideas for developing students’ critical thinking skills as well as enrichment activities are also included. There are teaching strategies to choose from such as: individual research, group work, play writing, debates and interviewing. The goal of this unit is to help students be aware of the global education principles of interconnectedness, awareness of other perspectives and appreciation of other cultures. It is hoped that students will be able to understand how the Mesoamerican societies from the past are connected to the present, how people from these societies saw their world and how we can learn and benefit from an understanding of these cultures. MAYAN WOMAN 3 ELEMENTS OF GLOBAL EDUCATION 1. INTERCONNECTEDNESS 2. AWARENESS OF OTHER PERSPECTIVES 3. APPRECIATION OF OTHER CULTURES 1. INTERCONNECTEDNESS As we move towards a more multicultural society and increased contact among peoples, there are a number of ways in which we experience the linkages with people and nations throughout the world. In order to understand these cultures today you have to look back and reflect upon their history. Past and present are linked. Objective: To promote among students an understanding of the connections between: - ideas - events - people and cultures - local and global issues - past and present 4 2. AWARENESS OF OTHER PERSPECTIVES The indigenous peoples of ancient Mesoamerica had a different world view than ours in some cases but it is a valuable one and has something to say to us. An example is their relationship with nature and in particular their creation myths. How did indigenous peoples relate to and see their universe and their place in it? Objective: To help students view concepts, ideas and events from a different and unique cultural perspective in order to enhance their global understanding. 3. APPRECIATION OF OTHER CULTURES The influence of ancient Mesoamerican cultures can be seen in many aspects of contemporary life today. People, then and now from Mesoamerica, have many things to offer us and we can learn from them. Objective: To have students recognize and respect the uniqueness of other cultures and how these cultures have enriched our own. 5 KEY UNDERSTANDINGS FOR THE STUDY OF THE AZTEC AND THE MAYAN CIVILIZATIONS 1. CITIES: (SUCH AS TENOCHTITLÁN, PALENQUE) - built in a variety of geographical and climatic areas - some were built in the highlands, and others in jungles or coastal regions - carefully planned, well laid out - central areas were reserved for religious and public buildings and the houses of rulers and the elite - houses of common people were outside these areas 2. STRATIFICATION OF SOCIETY - social order where everyone had their place - obligatory duties; in exchange, people were provided with security - central administration to maintain order, promote public works, provide justice - based on a monarchy 3. MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE; ENGINEERING INGENUITY - pyramids - ceremonial temples - palaces, tombs - massive stone sculptures - subterranean tile drainage systems and waste disposal MAYAN WEAVER 4. ART WORK - high quality artisanship - ceramics, pottery, scuplture, frescoes, murals, - ornaments, jewellery, figurines - fine feather and goldwork - accomplished weavers 6 5. INTELLECTUAL ACHIEVEMENT a. They each had two calendars, the solar and the sacred b. Their knowledge of astronomy led them to exact calculation of seasons and careful consideration of planting times c. Obsessed by counting and the passage of time - very detailed mathematical calculations - were familiar with the concept of 0 (the Mayas) d. Had a picture-writing (glyphs) system where an object was represented by a drawing; it was kept in books called codices most of which were destroyed by the Spanish e. Developed literature and poetry writing f. Vast knowledge of medicinal plants 6. RELIGION - religion touched almost every aspect of Mesoamerican life - was a cohesive force - worshipped many gods - each god connected with some aspect of nature or a natural force - to worship their gods, they built magnificent ceremonial centres, temples and pyramids - there existed a hierarchy of priest-rulers who: • held power and political authority • directed intellectual life • were scientists and cultural leaders BAT GLYPH (COPÁN) 7. WIDE COMMERICAL AND TRADING NETWORK - cities were joined by a network of roads - items such as cacao beans and feathers were in great demand and used to pay tribute - goods of all kinds were exchanged and all the products of the land were sold in busy marketplaces There was a general sense of order reflected throughout their societies. 7 NORTH AMERICA MEXICO CENTRAL AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN A. (see appendix A on page 66) B. (see appendix B on page 67) C. (see appendix C on page 68) 8 The region currently known as Mesoamerica covers the southern part of Mexico and the northern area of Central America. Two of the major advanced cultures that emerged in this area are the Mayas and the Aztecs. ELABORATELY DRESSED MAYAN WOMAN THE MAYAS T Their knowledge of medicine was superior to that of any other civilization of their time. Their agriculture, involving intensive farming with irrigation, was advanced enough to support large urban populations. he Mayan civilization began to develop around 2000 B.C. in southern Mexico and lasted till 1500 AD The Classic Age, the period of their greatest development, took place between 200 AD and 900 AD with the Mayan culture flourishing and spreading through southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, El Salvador and Honduras. Large and powerful centres were built and the people developed their own political systems, religious beliefs and forms of artistic expression. Unlike the Aztec empire that was controlled by a central government, the Mayas had a number of small city states and principalities. The Mayas shared a common culture and religion but each city governed itself and had its own noble ruler. Some of the important cities were Palenque, Chichén Itzá and Tikal. The Mayan civilization was noted for its many remarkable achievements. For reasons still unclear, by AD 900 many of the great cities and ceremonial centres were abandoned and left for the jungle to reclaim. In astronomy, they were more advanced than other ancient peoples. Records show that the Mayas had observed the skies for centuries, keeping track of what they saw. They knew how long the moon took to go around the earth, and how long the planet Venus took to come back to the same place in the sky. They could predict eclipses, and they worked out a calendar of 18 twenty-day months and one five-day month that measured the year even more accurately than the calendar we use today. The Postclassic period lasted from 900 AD to 1500 AD and saw the development of new centres of power and intense warfare. The arrival of the Spaniards in the first decades of the 16th century closed this phase of Mayan civilization. The Mayan people, however, did not cease to exist. There are at least four million descendants that still speak the Mayan languages. Although most of them are Roman Catholic, they continue to recount their ancients myths and practice their rituals, based on their ancestors’ view of the universe. They were the first to use the mathematical concept of zero, 500 years sooner than anyone else had thought of it.They developed a complex writing system, using a hieroglyphic script. Their art, architecture and sculpture were refined and sophisticated. They built monumental temples, pyramids and palaces, many of them to honour their gods. 9 THE AZTECS I t is said that the Aztecs came from a mysterious, far-off land in the northwest of Mexico called Aztlan—hence the name Aztec.They were a wandering band of people, numbering less than 5,000, looking for a place to live. In 1323 they arrived at some islands in the snake-infested swamps of Lake Texcoco in the valley of Mexico. Here, they saw the sign they had been promised by their god, Huitzilopochtli (Blue Hummingbird). The sign was an eagle with a snake in its beak, sitting on a cactus. They called the place Tenochtitlán and built their first dwellings round a temple to their god. They began draining the swamp and raised mud islands, held together by trees, in the middle of the lake. At first they built mud and reed huts. Over a period of time this gave way to more ornate temples and palaces. Three long causeways linked Tenochtitlán with the mainland on each side and the city was honey-combed with canals. They built a 15 km aqueduct to bring fresh water to the city. They also built a sewer system, flushing waste into the lake—a PYRAMID OF THE SUN TEOTIHUACÁN 10 feat of sanitary engineering unheard of at that time. Tenochtitlán became one the most beautiful cities in the Americas. The Aztecs grew in numbers, prospered and began to conquer the surrounding tribes. In time, the boundaries of the Aztec empire extended from northern Mexico into Guatemala and from the Gulf Coast to the Pacific Ocean. The Aztecs were well advanced in many areas. They developed a form of picture writing, devised a sacred calendar and built spectacular temples and pyramids.They had a highly centralized government and an elaborate religion. But Aztec society had its negative side. The Aztecs, like Europeans of the time, lived in a hierarchical society. At the top was the emperor, the supreme ruler, with the nobles and priests also holding much power.This small group controlled the mass of commoners and slaves at the bottom, which may have numbered up to five million people. The Aztecs practiced human sacrifice. In the centre of Tenochtitlán was the main pyramid used for sacrifice to Huitzilopochtli. The Sun God was also the God of War and the Aztecs believed he had chosen them to conquer the world. They felt they must offer their god the continual blood that he needed so that he could continue to rise in the east and triumph over the night. In order to please their god, it was necessary to be constantly offering him human sacrifices. They waged war on a continual basis in order to secure the victims for their sacrificial rites. In Aztec society, to die in battle or as a prisoner of war on the sacrificial altar was an ultimate privilege. Although Aztec society had its dark side, it was also a society that was unsurpassed in its achievements. The Aztec society continued to flourish until 1521, the year the Spanish conquered the Aztecs and the destruction of Tenochtitlán began. Today, the Aztec legacy can be noted in the Nahuatl language still spoken in the region, food and cooking, health care and numerous traditions that are still observed. Many aspects of contemporary life in Mexico and parts of Central America continue to be influenced by the Aztec culture. Aztec stone sacrificial altar Stone head of Quetzalcoatl, from the pyramid of Teotihuacán 11 FOOD T he principal food of the Mayas was maize (chim or ixim). It was eaten on every occasion. Other important foods were: fish, game, fowl, beans, squash, pumpkins, and sweet potato. A variety of fruits, such as the papaya and melon, were eaten. Chocolate was a favorite drink as was maize water and fermented honey. Mayan boys ate the fruit of the gum tree and chewed its gum. For the Aztecs, corn was also the central food in their diet. From this, tortillas (tlaxcalli) were made and a number of other dishes.The Aztecs ate many of the same things that the Mayas did. They cultivated avocado (ahuacatl), tomato (tomatl) and hot peppers (chile). Chile was used in many of their dishes. Cactus leaves were boiled and eaten by themselves or with main dishes. They drank pulque from the maguey plant and octli, a mild intoxicating drink, also derived from the maguey plant.They also drank atolli, a gruel made of maize flavoured with honey and chile. Everywhere, chocolate (chocolatl) was an important element of native culture. It was made with ground cacao beans and water. It was sweetened with honey and perfumed with vanilla. Prehispanic Mexican women ground their corn with stone mano and metate, and made tortillas much as many do today. From the Florentine Codex. 12 FOOD AND COOKING ACTIVITIES 1. Refer to the Geneological Tree of Corn (next page). a. Why was corn so important for the peoples of Mesoamerica? b. What are some ways that we use corn today? c. Do your own tree for one of the other products of the Americas (i.e. tomato, bean, chocolate, potato). d. See if you can find other recipes from Mexico and/or Central America. 2. a. In groups of 3 or 4, brainstorm a list of important food products in your society. b. Be prepared to explain why you think that product is important for your society. c. In pairs, select one of these products and Do a geneological tree. Find a recipe with this product. Write a story based on your product. 3. Recipes to make in your class: Chocolate Tortillas Guacamole Pollo Pibil See also SCIENCE Question 1 Container Cultivation and LITERATURE Mayan Legend of Corn. 13 14 RECIPES GUACAMOLE To make this dish, mash 3 very ripe avocados until smooth, add 2 tablespoons of finely minced onion, 1 teaspoon of salt, a dash of pepper, lemon juice to taste and either 2 teaspoons of chili powder or 1 chopped peeled green chile. Keep covered until serving time. Serve with tostadas, or as a sauce. Makes about 2 cups. A variation is to grind 2 tomatoes with the onion and chili and add to the mashed avocadoes. TORTILLAS 2 cups masa harina corn flour (Available in most supermarkets) 1 1/4–1 1/3 cups of water sheets of wax paper Mix the masa harina with water to make the dough hold together. Shape dough into 12 small balls. Place a ball of dough onto a square of waxed paper and flatten slightly. Cover with a second sheet of waxed paper and roll out into a circle (8–12 cm in diameter) with a rolling pin. You can cook the tortillas on a griddle or fry in deep fat until crisp and golden brown. To make a tostada, a variety of toppings can be placed on the tortilla such as: ground beef, shredded chicken, lettuce, tomatoes, cheese, sourcream, onion and avocado. MEXICAN CHOCOLATE 30 grams of unsweetened chocolate 1 tablespoon sugar pinch of salt 1/2 teaspoon cinnamon Combine these ingredients with 3 cups of milk and cook over hot water until the chocolate melts. Beat until foamy and serve hot. 15 CHILI PEPPERS THE TORTILLA ATOLE CHALUPA CHILAQUILES CORN FLAKES ELOTE ENCHILADA GARNACHAS GORDITAS HELADO DE ELOTE MASA NIXTAMAL PALOMITAS DE MAIZ PANUCHOS PENEQUES PINOLE POZOLE QUESADILLAS QUESADILLA SINCRONIZADA SOPES TACOS TAMAL TORTILLA TOSTADA TOTOPO JALISCIENSE — a corn flour gruel. — toasted tortilla topped with chicken, among other things. — cut-up tortillas in a green sauce with chicken or in a red chile sauce. — a popular Mexican substitute for breakfast. — corn. — rolled tortilla filled and covered with a sauce. — a tortilla with a beveled edge, filled with cheese, beans, shredded meat, etc. — a thick, stuffed tortilla. — Yucatecan corn ice cream. — ground up corn used to make tortillas, tamales, etc. — the corn meal used to make tamales. — the poetic way to say popcon — “little doves of corn.” — a tortilla filled with beans, fried and topped with the usual shredded chicken, lettuce, etc. — a boat shaped tortilla, pinched at the ends and filled with cheese or chopped meat, dipped in beaten egg and fried. — toasted and pulverized corn meal. — hog’n hominy “fire soup” garnished with sundry items such as marjoram, oregano, chopped onions, chile piquin (small and very hot chile), radishes, lettuce and toasted tortillas. — corn dough made into a Mexican version of a turover, filled with cheese, potatoe, meat, etc. and fried. — a tortilla sandwich with a cheese, ham and avocado filing. Strictly modern Mexican. — a small garnacha. — rolled, filled tortillas fried until hard. — masa dough filled with anything at all, wrapped in corn husks and steamed. — hand-patted or machine–flattened masa. — fried tortilla. — a toasted tortilla loaded with cheese, beans. Perhaps the most distinctive of all the cooking of Mexico is that of the Yucatán, where many Mayan people are to be found today. Many meat or fowl dishes are called pibil to tell that they are steamed in a pot, pib in Mayan. In some cases, the cooking is actually done in this way, but much more often the chicken or meat is wrapped in banana leaves and steamed for hours in a covered pot. Cochinita pibil (baked pork) is a big favourite all over Mexico. Other popular dishes include: Tzic de venado. This is baked venison, shredded and mixed with coriander leaves, radish, mint leaves and unsweetened orange juice. Sopa de lima is chicken broth with lime juice, tomato, onion and small pieces of chicken. A human head was shown as an ear of corn by the Mayas 16 POLLO PIBIL 2/3 cup fresh orange juice 1/3 cup fresh lemon juice 1 tablespoon annatto seeds, ground up (optional) 1 teaspoon finely chopped garlic 1/2 teaspoon dried oregano 1/2 teaspoon ground cumin seeds 1/4 teaspoon ground cloves 1/4 teaspoon ground cinnamon 2 teaspoons salt 1/4 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper A 2 to 2 1/2 kilo chicken, cut into 6 or 8 pieces 12 hot tortillas or ready-made tortillas In a small bowl, combine the orange and lemon juice, ground annatto seeds, garlic, oregano, cumin, clove, cinnamon, salt and pepper. Place the chicken in a shallow baking dish just large enough to hold the pieces snuggly in one layer and pour the fruit juice and seasonings over it. Cover the dish with plastic wrap and marinate the chicken for 6 hours at room temperature or overnight in the refrigerator, turning the pieces over in the marinade from time to time. Line a large colander with 2 crossed, overlapping sheets of aluminum foil and arrange the chicken on it. Pour in the marinade, then bring the ends of the foil up over the chicken and twist them together to seal in the chicken and its marinade securely. Place the colander in a deep pot, slightly larger in diameter than the colander, and pour enough water into the pot to within 3–5 cm of the bottom of the colander. Bring the water to a vigorous boil over high heat, cover the pot securely and reduce the heat to low. Steam for 1 3/4 hours, or until the chicken is tender, checking the pot from time to time and adding more boiling water if necessary. To serve, remove the package of chicken from the colander, open it, and take the chicken and all of its sauce to a heated bowl or platter. Serves 4–6. 17 SPELLING WORDS AND ACTIVITIES Many words still used today in Mesoamerica have origins in Nahuatl, the language spoken by the Aztecs. Some common words: ˘ ´ ¯ 1. atole (a-to-la) ¯ ´ ¯ 2. elote (e-lo-ta) ¯´ 3. chapulin (cha-pu-len) ¯ ¯ ´˘ ¯ 4. jitomate (he-to-ma-ta) a hot drink made of ground corn corn grasshopper tomato ¯ ˘ ´ ¯ 5. zopilote (zo-pi-lo-ta) ¯ ˘ ´¯ ¯ 6. molcajete (mol-ca-ha-ta) stone used to grind corn 7. coyote coyote ˘ ¯ ´¯ ¯ 8. guajolote (wa-ho-lo-ta) ¯ ´ ¯ 9. ayote (a-yo-ta) 10. tamale vulture turkey squash cornmeal dough with a sweet or savoury filling and steamed in corn or banana leaves There are at least 21 different Mayan languages that continue to be spoken by the people of Mesoamerica. Itzaj is one of those languages. Here are some examples: 1. juj iguana, lizard 2. cha’ gum 3. kan snake 4. put papaya 5. lemlem lightning 6. top’ flower 7. stoz bat 8. b’axal toy 9. et’ok friend 10. t’ot shell (Reprinted with permission from El Educador Union of Guatemalan Education Workers Bulletin Jan. Feb. 1994) 18 SPELLING ACTIVITIES Try and integrate the Spelling words into your writing activities such as: - diary entries - newspaper articles - a short story - poetry writing Do a visual dictionary or a poster with pictures of the words. Make up a crossword puzzle using the Spelling words. Make up a wordsearch using the Spelling words. See if you can find any words that we use that come from the Mayan and/or Nahuatl language. IMPORTANT MAYAN OFFICIAL 19 AZTEC LEGENDS THE LEGEND OF QUETZALCOATL F or many centuries, the indigenous people of Mexico honoured Quetzalcoatl as the god-king who not only created mankind with his own blood, but gave them the gift of corn. According to the legend, Quetzalcoatl—whose name means “plumed serpent”—was a blond, bearded white man. About 500 years before Columbus sailed for the New World, Quetzalcoatl ruled the Toltec Empire of Mexico. He was many things: an ancient god and culture hero, a patron of royalty and medicine, a teacher of the arts. One day, Quetzalcoatl summoned his people and, without warning, declared that he was going to return to the East, to the land of his birth. “I must go now,”, he said, “but I will make you one promise. I will return to you. I will sail back from the East in a ship with white wings. I will return during my birth year, Ce Acatl, One Reed.” The Aztec calendar was based on a cycle of 52 years.Ce Acatl was the date of Quetzalcoatl’s birth and his departure.Now, he said, it would also be the date of his return. Each 52 years, the people waited and prepared and prayed for the return of the god-king, Quetzalcoatl. As the years passed, the Toltec civilization weakened, and a greater new power, the Aztecs, took over. The Aztecs learned the legend of Quetzalcoatl. Every 52 years, they, too, waited for his return. The years went by—1363, 1415, 1467—all passed without Quetzalcoatl’s return. The next year for Quetzalcoatl’s possible return would be 1519. Everyone, including the powerful Aztec leader Montezuma,* made preparations. On April 21 in the year 1519, eleven strange ships appeared off the east coast of Mexico, near the spot where the city of Veracruz now stands. The ships had tall white sails, which looked to the natives like the “white wings” of which Quetzalcoatl had spoken. The men who stepped from the ships were white men just like QUEZALCOATL SAILING AWAY * also spelled Moctezuma 20 Quetzalcoatl. The leader of all the ships came forth, and he, too, was a white man, and he had a beard. Word of the strange, bearded white men soon reached Montezuma in his capital at Tenochtitlán, many miles inland. Had Quetzalcoatl, the white god-king of the old legends, returned to his people? Montezuma was not sure, but he sent a party of Aztec nobles, carrying rich gifts, to greet the white men. The leader of the men who came from the ships told the Aztecs that his name was Hernán Cortés. He said that he had been sent to their country by a great king, white like himself, who lived far to the east in a land called Spain. When the nobles returned to Montezuma and told him of this, the Emperor was certain that the old prophecy was being fulfilled. Montezuma invited Cortés to visit his capital city. On the long march from the coast to the capital, Cortés and his men provided even more reasons for Montezuma to believe that they were “white gods.” Cortés was attacked along the way by natives. However, they were easily defeated when the Spaniards used strange weapons which spate lightning and made noises like thunder. And some of the white men rode on strange, four-legged beasts called horses, which the natives had never seen before. When Cortés and his men reached the great city of Tenochtitlán, Montezuma himself came out to welcome them. He gave them many fine gifts and a large palace to live in. But just one week later, the Spaniards took Montezuma prisoner and the conquest of the Aztec Empire began. Quetzalcoatl, “Plumed Serpent” Templo Mayor, Mexico City 21 THE LEGEND OF POPOCATEPETL T he Mexican people have an ancient legend which explains the birth of two great volcanoes in the southeast of their country. One is named Iztaechualt, which means “the volcano of the sleeping woman.” Nearby is the volcano Popocatepetl, which even now can sometimes be seen glowing brightly in the evening sky. The legend tells us that many years ago, before the mountains we know today even existed, the land was ruled by a King who was very rich and powerful but also very greedy. He had a magnificent palace, great riches, a beautiful daughter named Izia and a strong, loyal army. But he was not satisfied. A brave young army officer named Popocatepetl loved the King’s beautiful daughter, but he could not tell her. Even in those ancient times, a captain, no matter how brave, did not marry a princess. One day the King invited all of his subjects to a great ball at the palace. There was dancing and singing and everyone was happy. The beautiful Princess saw the handsome Popocatepetl looking at her, and she smiled at him. This gave the young man courage, and he went to the King, fell on his knees, and declared his love for Princess Izia. The King listened silently as the captain asked for permission to marry the Princess. The King saw the chance to gain more territory by sending the captain on a nearly impossible mission. Without even asking his daughter about her feelings, he made the brave soldier a promise. The most powerful enemy of the King lived on the frontier of the kingdom. He had a strong army that was feared by everyone. No one had dared to challenge him. The king told Popocatepetl to take his soldiers and defeat this fearful enemy: if he was successful, he would marry the Princess. The young captain was so deeply in love that he agreed to go into battle against the nearly unbeatable enemy. When they were left alone, the Princess took off her scarf, kissed it and gave it to Popocatepetl, promising to remain loyal to him until her death.He took the scarf and courageously left for battle. Weeks passed, and Popocatepetl did not return. The Princess waited and waited for him, spending hours watching the road leading from the battlefield. Her companions tried to distract her with songs and dances, but she could not forget the dangers which the brave captain faced to win her. The time came when the Princess did not have the courage to watch the road any longer. She lay on her bed, refusing to take the food which was brought to her. The King heard of his daughter’s actions and went to see her. When she asked for news of Popocatepetl, the King told her that all of his warriors had been killed in a fierce battle in the northern frontier. The Princess cried that, if her beloved captain was dead, she had nothing left to live for. She lay back, shut her eyes, and never opened them again. The King understood then that, wishing to serve his greed, he had broken his daughter’s heart. 22 Suddenly, loud cries came from outside the palace. They were victory cries. Popocatepetl, after defeating the terrible enemy, was returning home to the cheers of the crowd. The happy soldier, still covered with dust from his long journey, hurried into the palace. He went to the King and reminded him of his promise of marriage. With great sorrow, the King told Popocatepetl that his daughter had died of a broken heart. The grief-stricken captain was taken to the Princess’ deathbed, where he wept, broke his arrows and sword and promised never to leave her side. He called his soldiers together and had them build a tomb, as tall as a mountain, for the Princess Izia. When the last stone was in place he took the Princess in his arms, climbed the mountain which would serve as her tomb and placed her at the top, near the sky. He lit a candle and began a solemn watch over the dead girl, promising to guard her forever. This candle is the flame of the volcano Popocatepetl, which still reddens the skies of the Mexican night, guarding over the volcano of the sleeping woman, Iztaechualt. Popocatapetl 23 THE FOUNDING OF THE CITY OF TENOCHTITLÁN T he Aztecs came into Anáhuac, the high, fertile valley of Mexico, in AD 1168. They were referred to at this time as the Tenochas or Mexicas. They were wanderers, a landless tribe who came from a mysterious, far-off land in the north-west of Mexico called Aztlan—hence the name Aztec, the people of Aztlan. At that time, they numbered 5,000, if that. According to their own legends, they had found, in a cave, the Hummingbird Wizard, the famous Huitzilopochtli.He gave them this advice: “You will be a great people if you will but follow my law. Wander until you find good lands, then plant them with maize and beans, avoid great wars until you are stronger, sacrifice to me the bleeding hearts of your captives.” He also told them that they were to look for an eagle perched on a cactus devouring a snake. This is where they should settle. Moctezuma’s grandson wrote this foundation legend in Nahuatl. “It is told, it is recounted here how the ancient ones.... the people of Aztlan, the Mexicans ....came to found the great city of MexicoTenochtitlán, their place of fame, their place of example, the place where the tenochtli cactus stands amidst the waters; where the eagle preens... and devours the snake...among the reeds, amid the canes.” Tezozomoc, Fernando Alvarado. Crónica Mexicayotl. The eagle perched on a cactus devouring a snake is the emblem on the Mexican flag. ´ 24 CORN “The gods made the first Maya-Quichés out of clay. Few survived. of corn. They molded their flesh with yellow corn and white corn. They were soft, lacking strength; they fell apart before they could walk. The women and men of corn saw as much as the gods. Their glance ranged over the whole world. Then the gods tried wood. The wooden dolls talked and walked but were dry; they had no blood nor substance, no memory and no purpose. They didn’t know how to talk to the gods, or couldn’t think of anything to say to them. The gods breathed on them and left their eyes forever clouded, because they didn’t want people to see over the horizon.” From the Pop Wuj Sacred Book of the Quichés Then the gods made mothers and fathers out 25 MAYAN STORIES These Mayan fables and animal stories were collected and transcribed by the author from the Jakaltek-Mayan language, one of the 21 Mayan languages that are still spoken in Guatemala. THE BIRD WHO CLEANS THE WORLD O ur Mayan ancestors spoke of a great flood that covered and destroyed the whole world. They said that the waters rose and rose and rose, flooding the highest mountains and hills and killing everything that lived on the earth. Only one house stood above the flood. In that house all the species of animals entered and hid themselves. The waters covered the earth for a long time. Then, very slowly, they began to recede, until finally the turbulent waters revealed the earth in its new freedom. When that house was still surrounded by water, they sent forth Ho ch’ok, the trumpet bird, to scout the horizon. Since the water was still high the trumpet bird returned quickly, its mission complete. After a little time more they sent Usmiq, the buzzard, to find out how much the water was receding. The messenger, circling through the air, left the house. After a while he flew toward one of the newly uncovered hills and landed with a great hunger. There he found a large number of dead and rotting animals. Forgetting his mission, he began to devour chunks of the meat until he satisfied his appetite. When he returned to make his report, the other animals would not let him in among them because his smell was unbearable. And to punish him for his disobedience, Usmiq was condemned to eat only dead animals and to clean the world of stench and rottenness. From that time on the buzzard has been called “The Bird Who Cleans the World” because his duty is to carry off in his beak all that might contaminate the land. Usmiq, the buzzard, had to be content with his fate, and thus he went away, forever flying and circling in the air or sitting on the bluffs looking for rotten things to eat. 26 WHO CUTS THE TREES CUTS HIS OWN LIFE W hen I was a small boy my father used to tell me, “Son, don’t cut the little green trees whenever you please. When you do that you are cutting short your own life and you will die slowly.” This warning always worried me, especially since at times I have carelessly cut some little tree by the side of the road with my machete. My father’s warning was nothing new, but something the old ones have said since distant times. And my father who knew their teachings, repeated it to me and my brothers. Now when I hear about pollution, erosion, and deforestation, I realize the value of the old philosophy. These things are signs of the slow death that our elders have always foreseen when they said, “Who cuts the trees as he pleases, cuts short his own life.” LAZINESS SHOULD NOT RULE US T hree jaguars were dying of hunger, but they didn’t want to go out into the forest to look for food. Just then Rabbit came upon them and asked with great concern, “Why are you complaining so, my friends?” “Well, we are dying for something to eat,” answered the jaguars. “What of these great claws and fangs? What are they for if not to catch your food?” “Yes,” the jaguars said, “But we would have to go out and look for it.” “Well, then,” Rabbit said,”you need someone to carry you out into the forest. Very good. I can carry all of you. Climb into this net.” So they quickly climbed into his net. Rabbit found a long green guava stick. With the stick he beat the jaguars. “Take this! This is what you deserve,” he shouted. “You are built like great hunters, but you don’t want to exert yourselves.” He whacked them hard again. “ This is what you deserve, you lazy beasts.” Rabbit left them lying there. The jaguars learned from that beating that laziness is the origin of much misfortune. “The Bird Who Cleans the World”, “He Who Cuts the Trees Cuts His Own Life” and “Laziness Should Not Rule Us” from Victor Montejo’s The Bird Who Cleans the World and Other Mayan Fables, translated by Wallace Kaufman. (Curbstone Press, 1991.) Reprinted with permission of Curbstone Press. Distributed by InBook. When they were in and the net was tied shut, 27 Bernal Diáz del Castillo On Entering Tenochtitlán .....We saw the fresh water which came from Chapultepec to supply the city, and the bridges that were constructed at intervals on the causeways...We saw a great number of canoes, some coming with provisions and others returning with cargo and merchandise....We saw cues (pyramids) and shrines in these cities that looked like gleaming white towers and castles: a marvellous sight. All the houses had flat roofs, and on the causeways were other small towers and shrines built like fortresses. Having examined and considered all we had seen, we turned back to the great market and the swarm of people buying and selling. The mere murmur of their voices talking was loud enough to be heard more than three miles away. Some of our soldiers who had been in many parts of the world, in Constantinople, in Rome, and all over Italy, said that they had never seen a market so well laid out, so large, so orderly, and so full of people. ..... When we saw all those cities and villages built in the water, and other great towns on dry land, and that straight and level causeway leading to Mexico, we were astounded. These great towns and cues and buildings rising from the water, all made of stone, seemed like an enchanted vision from the tale of Amadis. Indeed, some of our soldiers asked whether it was not all a dream. (Diáz del Castillo, Bernal. History of the Conquest of New Spain, BAE, Madrid: M. Rivadeneyra, 1879.) MARKET SQUARE 28 ACTIVITIES Read one of the famous myths/legends. Rewrite it in your own words. Illustrate it. Dramatize it. Read it aloud to the class. Compare it to a west coast native legend for style, characters and theme. How are they the same? Different? Are any of the legends trying to teach a lesson? If so, what is the lesson? Investigate to find out who were the major gods/goddesses. Do a brief write-up on each, a poster or a small book. Read Bernal Diáz del Castillo’s impressions on first seeing Tenochtitlán. What might you have felt had you discovered a city such as this? Write your impressions/response as a poem, prose or a word painting. DETAIL FROM TEMPLE OF QUETZALCOATL. TEOTIHUACÁN, MEXICO 29 WRITING ACTIVITIES 5. Find a creation myth from the west coast of B.C. How are these the same as the Aztec or Mayan legends? Compare style, characters, theme. How are they different? 1. Keep a diary for a week of a child living at that time: It could be a Maya or Aztec, rural or urban child. What would they do? eat? wear? study? 6. Make up an interview with a person living in one of those societies ( a leader, warrior, child, woman). Think about what they would do in the early hours of the day, during the day and before bedtime. Come up with 5 questions and answers. Illustrate your diary. 7. Some indigenous people of Mesoamerica continue with the custom of choosing a Nahual or animal to represent each newborn child. 2. Go back in time and visit one of the Aztec or Mayan sites. a) What would it be like? (pick some topics to focus on) What animal would you pick to represent yourself? Why? b) Write a letter home describing your experiences. Write a short paragraph on which animal you think represents you and why you think so. 3. Newspaper Do other cultures use animals as symbols? Share some examples. In groups, prepare a newspaper of that time. Include: a cooking section, sports page, weather, help wanted, advertisements, current events, letters to the editor and a crossword puzzle using some of the spelling words. 8. What things were the Mayas/Aztecs advanced in? What things do you think they were not advanced in? 4. Write your own legend using one of the following ideas as your focus or make up your own: Why corn is so important. The Mayan culture could be called “the splendid versus the barbaric.” This could also be said of the Aztecs. How the quetzal got its bright feathers. Explain what you think this means. How the cedar got its wrinkly bark. Illustrate this. Illustrate your legend. You could include a story map. Prepare a skit to be presented to the class that shows the paradox of the Mayan or Aztec society. 30 TEACHERS’ NOTES: The Mayas never grasped the principle of the wheel but They could calculate the movements of planets and predict eclipses with acccuracy not matched till the 20th century. They could not build a simple arch but Their system of mathematics was unrivalled even in ancient Egypt. They could count in millions and used the concept of 0 a thousand years before the rest of the world. Their only tools were made of wood or stone but They cut and moved rocks weighing thousands of kilograms, and built temples over 70 metres tall. Observatory Chichén Itzá 31 AZTEC POEMS The Aztecs were curious about their relation to the universe as a whole; they questioned themselves about life and afterlife. 1. Is it true that one lives only on earth? Not forever on earth:only a short while here. Even jade will crack, Even gold will break, Even quetzal feathers will rend, Not forever on earth: only a short while here. 2. If in one day we leave, In one night descend to the mysterious regions, Here we only came to meet, We are only passers-by on earth. Let us pass life in peace and pleasure; come, let us rejoice. But not those who live in wrath: the earth is very wide! That one could live forever, that one need not die. Mexico was virtually a sun kingdom. Above all was the sun god. 3. Now our father the Sun Sinks attired in rich plumes, Within an urn of precious stones, As if girdled with turquoise necklaces goes, Among ceaselessly falling flowers.... 4. Proudly stands the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlán, Here no one fears to die in war... Keep this in mind, oh princes... Who could attack Tenochtitlán? Who could shake the foundations of heaven? 32 MAYAN POETRY 1. Let the day begin, let the dawn come. Give us many good paths, clear and straight paths... Let the people have peace, peace in abundance, and be happy, and give us good life and a useful existence. 2. Let us not forget, nor erase from our memory or lose our way, look first to your country, look first to your homes, establish where you are from! Multiply and walk and go once again to the place from where we came. From the Pop Wuj 3. For the Maya, time was born and had a name when the sky didn’t exist and the earth had not yet awakened. The days set out from the east and started walking. The first day produced from its entrails the sky and the earth. The second day made the stairway for the rain to run down. The cycles of the sea and the land, and the multitude of things, were the work of the third day. The fourth day willed the earth and the sky to tilt so that they could meet. The fifth day decided that everyone had to work. The first light emanated from the sixth day. In places where there was nothing, the seventh day put soil; the eighth plunged its hands and feet in the soil. The ninth day created the nether worlds; the tenth earmarked for them those who had poison in their souls. Inside the sun, the eleventh day modeled stone and tree. It was the twelfth that made the wind. Wind blew, and it was called spirit because there was no death in it. The thirteenth day moistened the earth and kneaded the mud into a body like ours. Thus it is remembered in Yucatan. Sodi, Demetrio. The Literature of the Mayas. 33 POETRY ACTIVITIES 1. Refer to Aztec poem 3. What is being described here? Use specific references to the text and explain what the imagery conveys to you. 2. Refer to poem 3 of the Mayan poetry. Using a big sheet of blank paper, divide your paper into 13 boxes. Give a pictorial representation of the creation in each of the 13 frames as described in the poem. Do a comparative framework for the 7 days of creation as descibed in the Book of Genesis. Choose one other religion. Investigate its theory of Creation and create a framework that would illustrate it. 3. Choose another one of the poems and write what you think the poem is trying to say to the reader. Illustrate it. 4. Copy one of the poems from the Poetry section onto large white paper and illustrate it, focusing on the spirituality of the Mayas/Aztecs. Underneath, write your response to the poem. What do you think the poet is trying to say about life? death? creation? Include specific references to the poem to support your points. Itazamná (left) god of the sky and learning. Yum Kaax (right) was the god of corn. 34 POETRY WRITING Students can write poems using some of the following models: Shape Haiku Cinquain Stair 3 Line Location action subject Acronym poem The following topics can be used: an animal (hummingbird, jaguar, quetzal, serpent) plants (corn, cactus) nature (sun,rain,thunder) day, night war temples, pyramids EXAMPLES OF POETRY MODELS SHAPE POEM Brainstorm words and phrases that describe the topic the teacher has given you. Choose the words and phrases that you wish to use. Draw the object and fit the words into it. Color it. Pyramid tall, stone high in the sky stairway to the gods towering above for all to see 35 written by Richmond Students HAIKU Firefly Flying as if lost Lighting up the cold dark night Little star cousins James Harper -3 lines -5-7-5 syllables -reference to nature CINQUAIN Line 1 Line 2 Line 3 Line 4 Line 5 One word subject Two adjectives Three verbs A phrase Synonym for line 1 Space Black empty Living changing dying constantly growing and flowing universe Craig Lust STAIR POEM Ideas built up following a stair pattern Line 1 Topic, main idea Line 2 2 adjectives Line 3 A place or time connected with topic Line 4 A phrase Waiting to fly away. Up high in the banana tree Yellow, singing Bird Zahid Nanji 3 LINE Subject Location Action The butterfly in a cocoon spinning a new life form. Amrit Baidwan ACRONYM Write title vertically or horizontally (Space). Letters of the title are used to start the word or phrase. Sparkling, like diamonds the Particles in space Afloat everywhere Celebrating their voyage Endlessly in space. Annie Sandhu 36 MATH ACTIVITIES T he Mayas were excellent astronomers and could observe the solstices and equinoxes, and predict eclipses based on mathematical calculations that were very complex and advanced. The Mayas were very interested in mathematics and are credited with discovering the concept of zero. Their number system was based on units of 20 and called vigesimal. Our system is based on the number 10 and is called a decimal system. ACTIVITIES Make up some simple math questions using the Mayan numbers given below. Exchange with a classmate. Figure out your birthdate using Mayan numbers. Write the date using Mayan numbers. What is a solstice? an equinox? When do they occur? Draw diagrams to illustrate your explanations and label them. NUMERALES MAYAS 37 SCIENCE ACTIVITIES 1. CONTAINER CULTIVATION Plant black beans, different kinds of chile, groundcherry, cilantro. You could plant them in different sized containers and observe and chart their growth. Keep a record of your observations. Follow-up: Keep a journal. Record your inferences as you make observations. What are your conclusions? Find a recipe that uses one of these ingredients. If possible, make it and share it with classmates or Find 2 recipes. Which is the more nutritious food? Be prepared to support your decision. 2. INVESTIGATION Investigate to find out what was the importance of the cochineal. See what you can find out about the following and what they were used for: maguey hemp sapodilla ebony mahogany rosewood cacao tobacco mezcal chicle The maguey plant and how sap was gathered and stored until it became octli. Develop an information chart to include illustrations and a caption. Draw the raw material and finished product and include a short writeup to explain its use. Do you use any of the above products or do you have them in your house? 38 3. URBAN PLANNING Research one of the cities (Tenochtitlán, Tikal, Palenque) . What kind of buildings, temples and houses did they have? Design your own Mesoamerican city. Do a model of your city. 4. REPORT WRITING Do a report with a partner on one of the animals of the Americas or one of their sacred animals. Why were they considered sacred? How were these animals treated? What were they used for? 5. AGRICULTURE Slash and burn farming was used by many Mayan farmers. What does it mean? Why was this method used? What are the advantages/disadvantages of this? How might it have contributed to the great Mayan centres being abandoned? Follow-up: See if you can find some information on the kinds of agricultural methods the Aztecs used. Compare/contrast slash and burn methods with Aztec farming methods using a Venn Diagram. The Incas, another great civilization of the Americas, used a method of farming called terrace farming. Find out more about this and do a Triple Venn Diagram which shows all 3 types of farming. 6. ASTRONOMY The Aztecs used chinampa agriculture, a method by which they filled oval-shaped reed baskets with earth and anchored them to the shallow bottom of the lake with trees. Crops of vegetables and flowers were then grown on the fertile chinampas. What did the Aztec calendar look like? What were its components? On what was it based? How is it linked to the arrival of Cortés? What can you find out about the Mayas and their knowledge of astronomy? Why do you think the Aztecs and Mayas were so interested in astronomy? 39 40 MESOAMERICAN SOCIETIES SOCIAL STUDIES ACTIVITIES 1. Give 3 theories on who may have first visited the Americas. (Vikings, Japanese, Irish) Which theory makes the most sense to you? Why? Give reasons to support your answer. 2. Who first settled the Americas? Where did they come from? How might they have arrived? When might they have arrived? What is the evidence for this theory? 3. Map 1 On a world outline map, show the route(s) that all possible visitors might have used. Colour code the routes and include a key. 4. Draw and label 5 animals they may have found. Which of these would be considered natural resources? Which ones were used by the inhabitants? How were they used? 5. What were the first crops grown in Mesoamerica? Draw and label 5 of them and tell what they were used for. 6. What are the elements of a civilization? Which do you think would have developed first? second? Tikal 41 7. The following groups of people all developed their separate societies in Mesoamerica. Investigate the following to find out: a) who they were b) where they lived c) when d) their achievements e) any other important information -Aztecs -Mayas -Zapotecs -Mixtecs -Toltecs -Olmecs Produce a key visual for one of the above societies. Present information in: -Web form -Data retrieval chart -Another form of your choice Achievements Important people in the society Strengths AZTECS When Weaknesses Where 8. Map 2 On an outline map of Mexico and Central America place where each of the above societies lived. Colour code it and include a key. Detail from Temple of Quetzalcoatl. Teotihuacán, Mexico 42 9. Map 3 On an outline map of Mexico and Central America place the following: (Teachers may want to reproduce the reference map for students). - Tula - Tenochtitlán - Tehuacán Valley - Monte Alban - Mitla - Chichén Itzá - Palenque - Tikal - La Venta - Copán 10. Take one group from question 7 and do an in-depth study. Include: - the topics you need to cover - the questions you need to answer related to each topic - maps - drawings, diagrams and charts TEACHERS’ NOTES Also refer to pages 74-77 in the book 500 Years and Beyond for further activities. (If this resource is not available in your library you can contact the B.C.Global Education Project at the BCTF for a copy). Palenque 43 OTHER TOPICS FOR INVESTIGATION Religion Family Life Sports and Games The Market Festivals Dance and Music Warfare The Tribute State Medicine Artwork Weaving, featherwork, pottery El Castillo Chichén Itzá 44 ART ACTIVITIES 1. GOD’S EYES Form a cross with two sticks or wires and wind wool or cord around. Alternate colours. Smaller ones could be made into mobiles. 2. MURALS depicted daily life in the Americas (Reference: temple walls at Bonampak, the work of Diego Rivera) Examples of murals to do:(working in groups) a) Mayan or Aztec civilization, including as many elements of the civilization as you can b) A market scene in Tenochtitlán c) A Mayan ballgame or d) A scene at school such as recess on the playground Remember that murals should include as much detail as possible. 3. CODICES - were made of bark or deer skin - used to record events - only a few survive as the Spaniards burned most of them. Materials: brown cardboard cut into 8 1/2 by 11, paints, pencil crayons, felts, white paper slightly smaller than the cardboard. Students can work in groups of 4 or 5. Each group brainstorms important events in the last school year. Group decides which students will depict which events. Each student, on the white paper, represents that event, either by drawing or using symbols. Then pencil crayon, felts or paints can be used to color it in. When the group has finished, put events in order and glue on to the cardboard. Punch holes in each piece of cardboard, and thread wool or string through it. They can be stood up on a table to be displayed. If you want, both sides of the cardboard can be used. 45 4. MODELS Build a model of: - a pyramid - temple - city 5. DIORAMA 6. FRIEZE DESIGNS using Mesoamerican symbols (flowers, serpents, hummingbird). 7. VISUALIZATION Have your teacher read aloud Bernal Diáz del Castillo’s impressions on first arriving in Tenochtitlán. Visualize, then draw what the city might have looked like. Part of the city of Chichén Itzá was The Thousand Columns, a 5–acre plaza containing: - a huge temple - columned hills - sunken gardens - terraces - pyramids and temples Visualize, then draw The Thousand Columns. Be as detailed as possible. 8. POSTERS/MOBILES Find out what crops and animals were found in the Americas that had not been seen before. Draw a poster to illustrate some of them. Make a mobile. 46 9. STELA* (Reference: Stelae at Copán, Honduras.) A stela is a carved stone pillar commemorating important events in Mayan history. The greatest number of them are found at Copán in Honduras. The Mayas carved ornate stelae from huge pieces of limestone and obsidian, often covering the entire rock surface with intricate designs, glyphs, and pictures. They used stelae to record history and mark the passing of time as well as to mark the graves of important people. Use the outline on your right to create your own stela.Include important events in your life (entering school,making the team, first babysitting job).Use Mayan-style designs, glyphs and/or pictures. Compare the totem poles made by the native people of Canada with the stelae carved by the Mayas in Mesoamerica. In what ways are they similar? In what ways are they different? In making your comparison, consider the material from which each was made, the style in which each was decorated and the specific use to which each was put. Stela Carving a stela * Stela - singular Stelae- plural 47 CODICES Codices were made of carefully prepared paper cloth, made from fibres of the maguey plant or animal skin. The Mayan codices were written or painted on with fine brushes on long strips of bark paper, folded like screens and covered with a layer of chalky paste. There are only 4 Mayan codices left today. When the Spanish arrived, they burnt all the ones they could find. For the Spanish, the conquest meant the total destruction of all Mayan and Aztec knowledge, science, religion and traditions. MAGUEY PLANT 48 EXTENSION ACTIVITIES FOLLOW THE MAYAN TRAIL Plan an imaginary trip to visit the archaeological sites of Mesoamerica. What would you plan to see? What would be the points of interest? Focus on 2 or 3. Design and prepare a brochure with graphics, map, descriptions of what you will be visiting and your itinerary. Share with the class. Write a speech you would give if you were the tour guide on this trip. COMPARE AND CONTRAST Compare and contrast El Castillo of Chichén Itzá, Mexico and the pyramid of Cheops in Egypt. Look at ways in which they are the same and the ways they are different. Develop a diagram to organize similarities and differences. Working with a partner or in groups of 3, draw floor plans and diagrams of the exterior and interior of the tomb pyramid at Palenque and of an Egyptian tomb pyramid. Then, compare them. In what ways are they similar? In what ways are they different? Which pyramid is more technologically advanced in its construction? Which pyramid is more beautiful? Be prepared to explain your responses. As far as we know, there was no contact between the ancient Egyptian and Mesoamerican civilizations.Each civilization developed separately, without the knowledge, influence or aid of the other. Compare the accomplishments of the Egyptian and Mayan or Aztec civilizations. In what ways are they similar? In what ways are they different?. If there was, in fact, no exchange of information and ideas between these civilizations, what factors might account for the similarities? 49 WORD COURT TRIAL This is an imaginary court trial. Words are to be put on trial for the damage they have done. Examples are: Colonization Conquest Greed Domination Discovery Define the words using a dictionary.What do you think of when you hear these words? How do you think the people of Latin America feel when they hear these words? What do they mean to them? Choose one word and prepare a case for why you think this word has been damaging to the people of Latin America. PREDICTING If the classic age of the Aztecs or Mayas had never ended and had continued to evolve, where do you think the civilization would be today? What do you think the accomplishments would be in the 1990’s? Develop a diagram with headings such as agriculture, art, writing, mathematics and religion and put your predictions under these headings. Consider: Would they have maintained their beliefs or would scientific evidence have shifted their thinking? TIMELINE Do a timeline with diagrams, graphics and other art work to show the birth, rise and fall of Chichén Itzá (or Tikal or some other Mesoamerican city). You may want to include the year it was “rediscovered” or reclaimed from the jungle. 50 ARCHAEOLOGY Explain what an archaeologist does in preparing for a dig. Sketch the different tools she/he would use. Research government policy on the finding of artifacts in Mexico, Guatemala or Honduras. What are the laws and penalties around this? See if you can get any information about this with regards to artifacts in B.C. What would be some of the dangers an archaeologist might face? Pretend you are an archaeologist in the jungle and keep a diary of what you do and how you feel. Consider: climate, food, isolation, other people you are working with, fears you might have. Illustrate your diary. ART Create a mobile summarizing the important ideas learned about Mayas or Aztecs on one side, with illustrations on the flip side. Variation: With a different colour for each side of the cards, e.g., red/yellow, write the key understandings for Mayas on red side and key understandings for Aztecs on yellow side. WRITING Like the ancient Egyptians, the Mayas wrote in hieroglyphs, small pictures that stood for words or ideas. Think of ten ideas that are most important to you and design hieroglyphs to represent these ideas. Cross section of the Temple of Inscriptions, Palenque. It shows the long-lost stairway that led down to the grave of the high priest or ruler, Pa Kal. It was found in 1951 by Antonio Ruz, a Mexican archaeologist. 51 SPORTS In all Mayan cities there was a ball court where 2 teams played pok-a-tok. Each team struggled to force a heavy rubber ball through their opponent’s goal which was a heavy stone ring set on the wall of the court. It was played at a furious pace, sometimes so violent that players died during the game. Reliefs carved in the stone walls of the ball court show the decapitation of a ball player and on a nearby platform are carvings of skulls skewered on sticks. If you were an archaeologist, how would you interpret these carvings? MATH SCALE DRAWINGS Draw a scale diagram on a blank white sheet showing: a) your height b) an Aztec pyramid c) a Mayan pyramid d) Cheops pyramid in Egypt CONNECTIONS In what ways have the indigenous cultures of the Aztecs and Mayas influenced the culture of Mexico/Central America today? What has come into our society from Mesoamerica? Using the headings food, plants, animals, vocabulary, science and any other ones that you can think of, list what we use or have today that has come to us from Mesoamerica. Variation: You may want to illustrate your list or present the information in the form of a codice (see Art Activities). 52 WHAT IS GOING ON? Note: Teachers are to read the following descriptions to their class. Do not tell students what each description is about. The first paragraph deals with an Aztec sacrifice. The second one is a North American hockey game. 1. The screams of the victim echoed off the hills. Warm blood ran down the cold altar steps. The High Priest plunged his old hand into the opened chest and pulled, pulled until the vessels snapped and a fountain of blood spat into the clear blue sky. He gave a shout of satisfaction and held the heart high above the altar, the blood running freely down his arm. 2. The men appeared to be following a small disc, hitting it with a curved object clasped between two of their limbs. It was not certain what the object of the ceremony was, but I was guided by the ecstatic cries of the crowd. Sometimes they would cry aloud if the disc became enmeshed in a kind of cage, but the climax of worship came when several of the creatures rushed upon one unfortunate victim, thrashing with their limbs. The roar was so deafening that I had to close my ears to it. Slowly the tumult died and I think the creatures were satisfied when they saw red matter emerge from the nucleus of their fellow creature. The teacher may then want to ask some of the following questions. a) Do you think these events describe something on this planet? b) What do you think is being described in each story? c) Have the observations anything to do with religion? Why would you think that? d) How do you think the victim in each case felt? e) If you were one of the participants, would you rather take part in the first or second story? EXTENSION ACTIVITY: A family has been informed that their son, a fine Aztec warrior, has been selected as a sacrifice to the gods. The father is proud of this as this is the ultimate honour but the mother reacts differently. Act out a probable argument that develops between the two. Try to reach an agreement. How does this compare to your beliefs? Present your findings to the class. 53 GIVE A THEORY The ruins of once-beautiful cities in the jungles of Mexico and Central America tell scientists much about the amazing people who built them. But they do not tell why these cities were suddenly abandoned over one thousand years ago. Around 900 A.D., something mysterious happened to the Mayan civilization. Activity stopped in the cities. Walls and foundations for new buildings were left unfinished. To modern archaeologists it looked as if the cities had been abandoned. WHAT HAPPENED TO THE MAYAS? Below are listed some theories as to why the great Mayan centres were abandoned. Can you think of any other reasons? Choose one of the theories and write a play or story about what might have happened. Some explanations given for the collapse of the great cities are: 1. The agricultural system collapsed and their food supply failed. The soil was exhausted and as the population increased, there wasn’t enough land around the cities to grow all the corn that was needed. 2. Overexploitation of the rainforest ecosystem, on which the Mayas depended for food. 3. Water shortages might have played a role in the collapse. 4. Overpopulation was another problem. Mayanists estimate that there were as many as 200 people per sq km in the southern lowlands of Central America which is a very high figure. 5. Overpopulation and a disintegrating agricultural system could have lead to malnutrition. 6. An earthquake. 7. Disease killed off the Mayas. Or did disease perhaps weaken them so much that they moved away from the cities to look for healthier surroundings? 8. Invasion from other tribes caused their downfall. 9. Revolt by the commoners and slaves against the unproductive, religious priests and rulers. The people may have resented the increasing demands of the priests for food and labor to build the temples. 10. The common people simply gave up their struggle against the heat, jungle and increasing demands of the rulers and moved away from the centres and into the forests. 54 PROPHECY I n 1519, Moctezuma, the Aztec emperor, awaited the return of Quetzalcoatl. There were a number of events that occurred that lead him to believe that something dreadful was to happen. Below is a story that tells of some of these events. One day long ago, the soothsayers flew to the cave of the mother of the god of war. The witch, who had not washed for eight centuries, did not smile or greet them. Without thanking them, she accepted their gifts—cloth, skins, feathers— and listened sourly to their news. Mexico, the soothsayers told her, is mistress and queen, and all cities are under her orders. The old woman grunted her sole comment: The Aztecs have defeated the others, she said, and others will come who will defeat the Aztecs. Time passed. For the past ten years, portents have been piling up. A bonfire leaked flames from the middle of the sky for a whole night. Another temple was burned by a flash of lightning one evening when there was no storm. The lake in which the city is situated turned into a boiling cauldron. The waters rose, whitehot, towering with fury, carrying away houses, even tearing up foundations. Fishermen’s nets brought up an ash-coloured bird along with the fish. On the bird’s head there was a round mirror. In the mirror, Emperor Moctezuma saw advancing an army of soldiers who ran on the legs of deer, and he heard their war cries. Then the soothsayers, who could neither read the mirror nor had eyes to see the two-headed monsters that implacably haunted Moctezuma’s sleeping and waking hours, were punished. Every night the cries of an unseen woman startle all who sleep in Tenochtitlán and in Tlatelolco. My little children, she cries, now we have to go far from here! There is no wall that the woman’s cry does not pierce: Where shall we go, my little children? A sudden three-tongued fire came up from the horizon and flew to meet the sun. Davies, Nigel. Los Aztecas. Tibón, Gutierre. Historia del nombre y de la fundación de México. The house of the god of war committed suicide, setting fire to itself. Buckets of water were thrown on it, and the water enlivened the flames. 55 SOMETHING TO THINK ABOUT T he events in the above story took place in 1519, which was also the year that Quetzalcoatl might reappear (see The Legend of Quetzalcoatl). Do you think all that happened was a coincidence or do you think it might be something else? What other explanation can you give for the events that took place in the story and the fact that Cortés came to Mexico the same year as Quetzalcoatl was to return? Have you ever had something happen to you that you feel is out of the ordinary such as “déjà vu” (this has already happened to me) or ESP? How do you think these events contributed to the defeat of the Aztecs? Illustrate the passage and include as many details as possible. An Aztec picture of the comet seen over Tenochtitlán in One Reed. Some astrologers tried to soothe Montezuma by saying it had never appeared! Others foretold terrible disasters. 56 SACRIFICE I t is said that the gods gathered in the twilight at Teotihuacán, and one of them, the Hummingbird Wizard, Huitzilopochtli, threw himself into a huge brazier as a sacrifice. He rose from the blazing coals changed into a sun; but this new sun was motionless, it needed blood to move. So the gods immolated themselves, and the sun, drawing life from their death, began its course across the sky. To keep the sun moving in its course, so that the darkness should not overwhelm the world forever, it was necessary to feed it every day with its food ‘the precious water’—that is, with human blood. Sacrifice was a sacred duty towards the sun and a necessity for the welfare of men, without it the very life of the world would stop. Every time that a priest on the top of a pyramid held up the bleeding heart of a man and then placed it in the sacred vessel the disaster that perpetually threatened to fall upon the world was postponed once more. sidered a great honour to be sacrificed. But the Aztecs needed more victims and to obtain them, there were ceaseless little wars. It was the sacred duty of every Aztec to take prisoners for sacrifce in order to obtain for the Hummingbird Wizard the nectar of the gods—human blood and hearts. War, eternal war, then was bound up with religion. How else could human hearts be obtained? A long peace was dangerous and war thus became the natural condition of the Aztecs for if the gods were not nourished they would cease to protect man from the other gods and this might lead to the total destruction of the world. Sacrifice was inspired neither by cruelty nor by hatred. It was their response, and the only response that they could conceive to the instability of a continually threatened world. Blood was necessary to save this world and the men in it. The victim was no longer an enemy who was to be killed but a messenger who was sent to the gods. In the most usual form of the HUITZILOPOCHTLI sacrificial rite the victim was And the victims, who had been God of war stretched out on his back on a prepared from childhood, acslightly convex stone with his arms and legs held cepted their fate. by four priests, while a fifth ripped him open with a flint knife and tore out his heart. There From Von Hagen, Victor. were also sacrifices of beautiful women to the The Aztec Man and His Tribe. goddesses of the earth and of children to the Soustelle, Jacques. rain-god, Tlaloc. The Aztecs used some of their Daily Life of the Aztecs. own citizens as sacrificial victims and it was con- 57 Based on what you have just read, give the reasons that the Aztecs sacrificed humans. Do you think it was an honour to be sacrificed? Why? Every culture possesses its ideas of what is and what is not cruel. The Aztecs were horrified when they saw the senseless torture, burning and killing carried out by the Spaniards when they arrived in 1519. For the Aztecs, the killings were done quickly for the most part and they were carried out with a definite purpose in mind. They also could not understand the Spanish Inquisition. What was the Inquisition? When was it started? Why was it started? The Aztecs did not like to kill their enemy on the battlefield. They would rather take them as prisoners. Can you think of a reason for this? Can you think of any examples in our society that might seem cruel to someone from another culture? Are there practices carried out in other cultures that seem cruel to you? ‘Flowery death’: the ultimate Aztec privilege was death on the sacrificial altar, where thousands of young Aztecs offered their lives to nourish bloodthirsty Huitzilopochtli, god of war (From the Codex Magliabecchi). 58 MAYAN BEAUTY SECRETS “Slightly crossed eyes were held in great esteem,” writes Yale anthropologist Michael Coe in his book The Maya. “Parents attempted to induce the condition by hanging small beads over the noses of their children.” The Mayas also seemed to go in for shaping their children’s skulls: they liked to flatten them (although this may have simply been the inadvertent result of strapping babies to cradle boards) or squeeze them into a cone. Some Mayanists speculate that the conehead effect was the result of trying to approximate the shape of an ear of corn. The Maya filed their teeth, sometimes into a T shape and sometimes to a point. They also inlaid their teeth with small, round plaques of jade or pyrite. According to Coe, young men painted themselves black until marriage and later engaged in ritual tattooing and scarring. From Time August 9, 1993 p.48 Secrets of the Maya. Copywright 1993 Time Inc. Reprinted by permission. What do we do in our society to make ourselves more attractive? Are any of these practices painful? Can you think of any practices that are dangerous? Can you think of what people in other societies do to make themselves more attractive? What is beauty and who determines it? Above Artificially flattening the head. Below A Mayan beauty feature was the squint created be hanging a ball in front of the eyes. 59 MISCELLANEOUS PLAY BALL A n important game was a ballgame called pok-a-tok by the Mayas and tlachtli by the Aztecs. It had religious significance for many Mesoamerican cultures. No one knows exactly how the game was played, but we do know that it was played by two teams, each with two or three players, using a solid rubber ball in specially made courts. The game was dangerous because of the speed at which the ball was propelled from one side of the court to the other using the hips. Using the hands and feet was not allowed. Spectators gambled on the competition’s outcome. There were many beliefs surrounding the ballgame. The game’s violent competition was a symbol of the battle between darkness (night) and light (day) and was a re-enactment of the death and rebirth of the sun. People also believed that the more they played the ballgame, the better their harvest would be. The solid rubber ball, which may have symbolized the sun or the moon, was kept in constant motion in the air, like the movements of the planets. The players may also have attempted to re-enact the battles they had won. Human sacrifice frequently provided the grisly finale of a game; sometimes the defeated players were sacrificed and their heads possibly used as balls. MAYAN BALL GAME 60 LIGHT AND MAGIC D uring the spring and fall equinoxes every year, crowds of tourists gather around El Castillo of Chichén Itzá to watch the setting sun’s shadow slowly move up the staircase that begins with two massive serpent heads carved at the base. The pyramid was dedicated to Kukulcan, a powerful god of creation and transformation. Its four staircases have 91 steps each, which, added to the top platform, equal 365, the number of days in the solar year, reflecting the Mayas advanced knowledge of astronomy. The serpent heads point directly to a natural well where human bones and gold jewelry, evidence of ritual sacrifice, have been found. BLOOD HARVEST T he gruesome ritual of bloodletting accompanied every major political and religious event in ancient Mayan society. In one engraving, the wife of a ruler is seen pulling a rope through her tongue. Blood dripped onto pieces of bark paper, which were burned as offerings to the gods. The intense pain of such rites led to hallucinatory visions that allowed participants to communicate with ancestors and mythological beings. From Time, August 9, 1993 Secrets of the Maya Temple of Inscriptions Palenque 61 CALENDARS The Aztecs had two calendars: the religious one, tonalpohualli, consisting of 260 days; and a second one which was a solar calendar, called xiuhmolpilli. The first calendar was magical and sacred. Its cycle consisted of 20 periods of 13 days. The solar calendar was 365 days long and had 18 months of 20 days each. The remaining five days, called the empty days, memontemi, were the unlucky days. Fires were extinguished, fasting was general and business was stopped. Everyone waited to see if the world would end. After the five days were over and they saw the sun rise once more, people resumed their duties knowing that life would go on once more. T he Mayas had very similar calendars. One calendar was the tzolquin or lunar calendar of 260 days and the other was the civil calendar called haab of 365 days. The lunar one was used to determine religious ceremonies. The civil calendar was made up of 18 months of 20 days each plus five days that were thought to be bad luck days called uayeb. The haab was a solar calendar, based on the time that it took the earth to go around the sun. It was very important for the farmers as it determined the growing seasons. 18 glyphs representing Mayan months, including the 5day unlucky Uayeb period Aztec Solar Calendar was divided into these 20 months. For both the Mayas and the Aztecs, the first day of each calendar occurred at the same time only once every 52 years.They believed that at the end of the 52 year cycle the future of the world was in balance and might be destroyed. (See the Legend of Quetzalcoatl in Literature). 62 PRONUNCIATION KEY Anáhuac ˘ ˘ ˘ an-a-wok chocolate ¯ ¯ ˘ ¯ cho-ko-la-ta guacamole ˘ ˘ ´¯ ¯ gwa-ka-mo-la Huitzilopochtli ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ ¯ wet-ze-lo-potch-tle Iztaechualt ¯ ˘ ˘ es-ta-shwalt Nahual ¯ ˘ na-wal Nahuatl ¯ ´˘ na-wa-tl pollo pibil ´ ¯ pebel ¯ ¯ poyo Popocatepetl ¯ ¯ ˘ ˘ ´˘ po-po-ka-te-petl Quetzalcoatl ˘ ˘ ´˘ ketz-el-kwa-tel Tenochtitlán ˘ ¯ ¯ ˘ te-noch-tet-lan Teotihuacán ¯ ¯ ¯ ˘ ˘´ ta-o-te-wa-kan ´ 63 BIBLIOGRAPHY ORIGINAL SOURCES Casas, Bartolomé de las. History of the Indies. Translated and edited by Andree M. Collard. Harper and Row Torchbook. 1971. Díaz del Castillo, Bernal. The Bernal Díaz Chronicles. Translated and edited by Albert Idell. Doubleday, New York. 1956. León Portilla, Miguel. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Beacon Press,Boston, MA. 1962. Recinos, Adrian (translator). Popol Vuh. The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 1950. Tezozómoc, Fernando Alvarado. Crónica Mexicayotl. Imprenta Universitaria, Mexico City. 1949. Tibón, Gutierre. Historia del nombre y de la fundación de México. FCE, México. 1975. RECOMMENDED SOURCES Davies, Nigel. The Ancient Kingdoms of Mexico. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth. 1982. Davies, Nigel. The Aztecs. Macmillan, London Ltd. 1973. Galeano, Eduardo. Memory of Fire: Century of the Wind (Three volumes: Genesis. 1987; Faces and Masks. 1988; Century of the Wind. 1988.) Pantheon Books, New York. Kuczma, Carmen. (ed) 500 Years and Beyond: A Teachers’ Resource Guide. CoDevelopment Canada, Vancouver. 1992. 64 Montejo, Victor. The Bird Who Cleans the World and Other Mayan Fables. Curbstone Press, Willimantic, CT. 1991. National Geographic. October 1989. “La Ruta Maya”. National Geographic. September 1987. “Jade - Stone Of Heaven”. National Geographic. April 1986. “Rió Azul Lost City of the Maya”. National Geographic. December 1980. “The Aztecs”. Soustelle, Jacques. Daily Life of the Aztecs. Penguin Books, Harmondsworth. 1964. Vaillant, George C. The Aztecs of Mexico. Pelican Books, Harmondsworth. 1950. Wright, Ronald. Stolen Continents. Viking Penguin Books, Toronto. 1992. 65 Appendix A NORTH AMERICA 66 MEXICO, CENTRAL AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN Appendix B 67 Appendix C 68