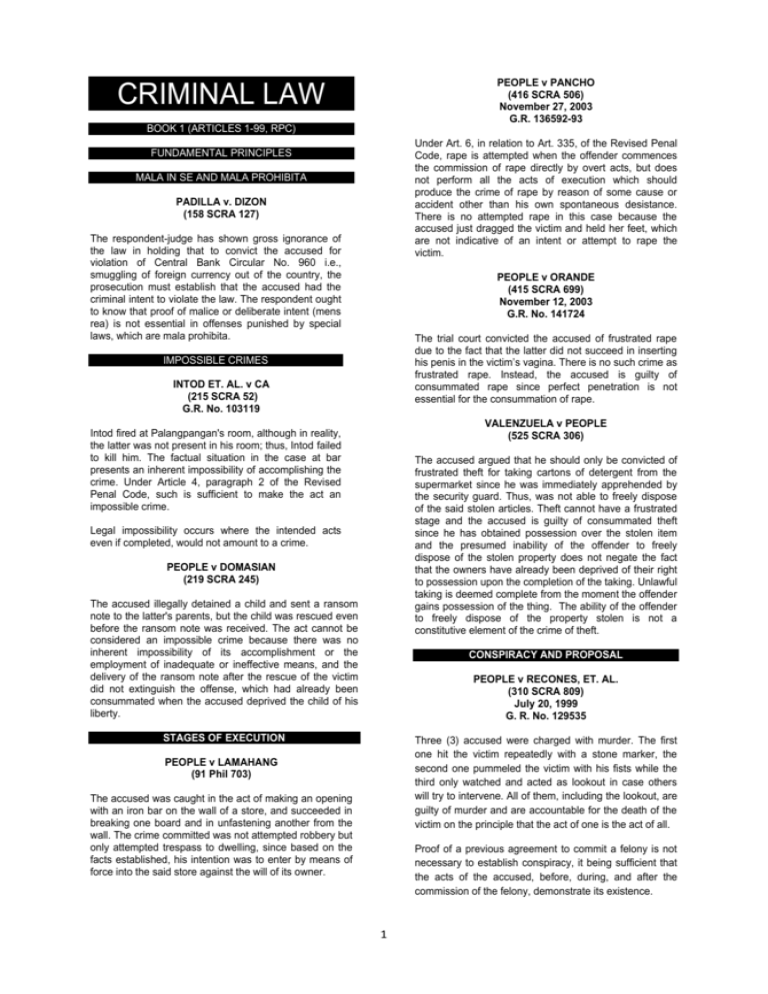

criminal law - Uber Digests

advertisement