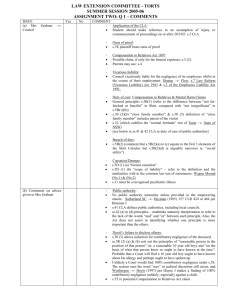

CA Decision

advertisement