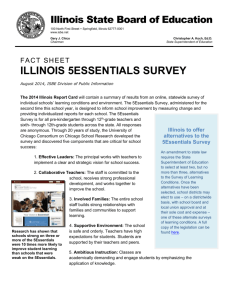

A First Look at the 5Essentials in Illinois Schools

advertisement