Jonathan A. Milian Florida International University

advertisement

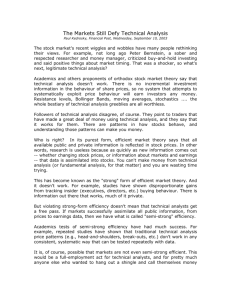

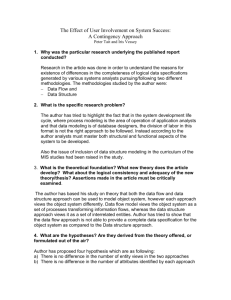

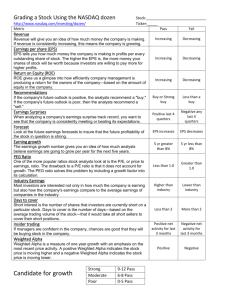

An Investigation of Analysts’ Praise of Management during Earnings Conference Calls Jonathan A. Milian Florida International University jamilia@fiu.edu Antoinette L. Smith Florida International University smithal@fiu.edu April 2015 ABSTRACT Through the textual analysis of a large sample of earnings conference calls, we find that analysts praise management on over half of earnings conference calls by saying complimentary phrases such as “congratulations on the great quarter.” Our results show that analysts’ complimentary phrases reflect the nature of the information released at the earnings announcement. We find that the amount of praise by analysts on an earnings conference call is strongly associated with the earnings surprise and to a greater extent the earnings announcement stock return. We also find that there is value to investors in tracking analysts’ flattery of management during earnings conference calls as it predicts abnormal stock returns over the following quarter. Our findings, which are incremental to prior research on the tone of earnings conference calls, highlight a previously ignored aspect of analyst feedback. Keywords: Earnings Conference Calls, Textual Analysis, Analyst Feedback, Compliments, Praise, Flattery Corresponding Author. We thank Andrew Leone for instruction on textual analysis, Elio Alfonso, Brent Lao, and Kelly Huang for helpful comments, and Mohammed Nazrul Islam, Martin Kim, and Sheng Yi for excellent research assistance. Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2685437 1. INTRODUCTION From the stock price reaction to a firm’s earnings announcement, capital market participants receive immediate evaluation of the firm’s earnings results and managers receive immediate feedback on firm performance. Earnings conference calls, which are commonly held shortly after firms announce their earnings results, provide the opportunity for immediate verbal feedback from analysts who follow the firm. Theoretical research suggests that managers can benefit both from the feedback in stock price reactions (Dye and Sridhar 2002) and from analysts’ feedback (Langberg and Sivaramakrishnan 2010). While feedback from analysts is naturally assumed to take the form of revisions in analysts’ forecasts, anecdotal evidence and the casual reading of earnings conference call transcripts suggests that analysts also provide feedback to managers in the form of verbal praise during the question and answer portion of the earnings conference call by using phrases such as “great quarter,” “good job,” and “congratulations.”1 This paper documents the prevalence of complimentary phrases by analysts during earnings conference calls and determines the extent to which this praise serves as both an indicator of current performance and a predictor of future performance.2 Prior research has not directly examined the praise provided by analysts during earnings conference calls. Documenting the prevalence of this practice is interesting and important. Prior studies indicate that subtle measures of earnings conference call sentiment (e.g., tone) contain significant information (i.e., correlates with the earnings announcement news and predicts future On his television show Mad Money, Jim Cramer suggests that investors track the number of “congratulations” spoken by the analysts during a firm’s earnings conference call (see the 4:17 and 4:18 clips from the March 18, 2010 episode, available at: https://archive.org/details/CNBC_20100318_080000_Mad_Money#start/1080/end/1140). We are unaware of any empirical evidence on the validity of this suggestion. 2 Throughout the paper, we use the terms compliments, praise, and flattery interchangeably. 1 1 Electronic copy available at: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2685437 returns, analyst forecast revisions, analyst target price revisions, and analyst recommendations).3 These studies use the frequency of positive and negative words in earnings conference call transcripts to measure tone, typically based on the positive and negative word lists of Loughran and McDonald (2011).4 For example, Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss (2012) find that the tone of an earnings conference call has significant explanatory power regarding the concurrent abnormal stock return and predictive power regarding the post-announcement abnormal stock return. Brockman, Li, and Price (2015) extend this finding by separating the tone of management and the tone of the analysts. They find that while the tone of both parties is informative, analysts’ tone is relatively more informative. We conjecture that if analysts’ praise of management is prevalent on earnings conference calls, then quantifying this praise can more directly capture the sentiment of analysts and the feedback received by management.5 Even if analysts’ praise of management is common on earnings conference calls, it is not necessarily useful information. Analysts may use compliments to curry favor with management rather than as a means to reveal their unbiased assessment of firm performance. Prior research suggests that more favorable analysts have better access to information (e.g., Chen and Matsumoto 2006; Ke and Yu 2006) and are more likely to be called on during earnings conference calls (Mayew 2008; Cohen, Lou, and Malloy 2014). Thus, if compliments on earnings conference calls are largely blatant attempts by analysts to ingratiate themselves with management, then a more subtle measure of analysts’ sentiment, such as tone, may better reflect 3 Studies examining conference call tone include: Allee and DeAngelis (2015), Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss (2012), Brockman, Li, and Price (2015), Druz, Wagner, and Zeckhauser (2014), Chen, Nagar, and Schoenfeld (2014), and Sinha and Huang (2014). 4 Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss (2012) use the Harvard General Inquirer and Henry (2008) word lists. Allee and DeAngelis (2015), Druz, Wagner, and Zeckhauser (2014), Brockman, Li, and Price (2015), Chen, Nagar, and Schoenfeld (2014), and Sinha and Huang (2014) use the Loughran and McDonald (2011) word lists. 5 We focus solely on analysts’ praise of management because we did not come across any instances of analysts’ overtly criticizing a firm’s management or performance in our reading of earnings conference call transcripts. 2 analysts’ true sentiment. However, if analysts are mainly objective in their provision of compliments, then we should expect a strong association between compliments and firm performance. Therefore, we empirically investigate whether there is any value in tracking the amount of compliments by analysts on earnings conference calls. We begin by developing a list of complimentary phrases that analysts typically use on earnings conference calls. Our list consists of a fairly narrow set of specific phrases such as: “good job,” “great year,” “nice quarter,” and “congratulations.” Section 3 provides a complete description of our list of phrases. We create our list from our understanding of the typical language used by analysts during earnings conference calls which we develop by reading dozens of earnings conference call transcripts and from conducting textual analysis on earnings conference call transcripts to understand which words most commonly follow the positive words from the Loughran and McDonald (2011) list. For example, when a positive word such as “great” modifies a word related to performance such as “quarter,” we classify the phrase as a compliment. However, when a positive word such as “good” modifies a word that is unrelated to performance such as “morning,” we do not classify the phrase as a compliment. Although our list is more narrowly focused than any of the commonly used positive word lists (i.e., Loughran and McDonald (2011), Henry (2008), Harvard’s General Inquirer, and Diction), our increase in specificity reduces noise and potentially better reflects analysts’ sentiment in the specific context of earnings conference calls. We then use textual analysis to search the transcripts of earnings conference calls for occurrences of the complimentary phrases from our list. We conduct our analysis on a large sample of earnings conference call transcripts by S&P 500 firms during the 2003 through 2013 period. We manually download our sample of 16,609 transcripts from Thomson Reuters 3 Datastream. In addition to counting the number of complimentary phrases spoken by analysts during an earnings conference call, we also perform word counts and measure the tone of both the overall conference call and the analysts’ portion of the conference call. We find that complimentary phrases are a prevalent way that analysts express themselves on earnings conference calls. At least one complimentary phrase by an analyst occurs in over half of the earnings conference calls in our sample. Consistent with analysts using flattery when the firm exceeded their expectations, we find that the amount of analyst compliments is positively related to the firm’s earnings surprise. We also find a strong relation between the earnings announcement stock return and the number of compliments during the earnings conference call. The economic magnitude of the association between compliments and earnings announcement stock returns is more than three times that of the association between earnings announcement stock returns and either analysts’ tone or management’s tone. This suggests that our list of complimentary phrases more directly captures analysts’ sentiment and the nature of the news released at the earnings announcement. We also find that there is value in tracking the number of complimentary phrases spoken by analysts during earnings conference calls as it predicts abnormal stock returns over the following quarter. This suggests that analysts’ compliments are a good proxy for qualitative information that investors underreact to. While there are other possible explanations for why analysts’ compliments predict future stock returns, this finding is consistent with analysts’ compliments on earnings conference calls being a helpful form of feedback to managers.6 The predictive ability of analyst compliments subsumes the predictive ability of the overall Another potential explanation is that analysts’ compliments preempt revisions in analyst forecasts. However, in untabulated results, we do not find that abnormal returns are concentrated in the first few days after the earnings announcement, which is the time when analysts most commonly revise their forecasts (e.g., Ivkovic and Jegadeesh 2004) and we continue to find evidence of a drift after controlling for analysts’ earnings forecast revisions occurring in the week following the earnings conference call. 6 4 conference call tone. While the predictive ability of compliments is modest (i.e., a two standard deviation change in compliments is associated with a 0.86% abnormal return over the following 60 trading days), this probably reflects our sample of S&P 500 firms which likely consists of more efficiently priced firms. We contribute to the literature by building on the ideas in Loughran and McDonald (2011 and 2015) and Allee and DeAngelis (2015) that textual analysis is context specific. For example, while phrases such as “good morning,” “good afternoon,” and “great thanks” are spoken extremely often by analysts during earnings conference calls, we show that analyst phrases specifically related to performance such as “great job,” “good year,” and “great quarter” better reflect analysts’ sentiment and the feedback received by management than typical tone measures. We also contribute by proposing that the verbal praise by analysts on earnings conference calls is a beneficial form of feedback to managers that can help them in their decision making (Langberg and Sivaramakrishnan 2010).7 This contrasts with Park, Westphal, and Stern (2011) which find that the flattery of management by board members leads to management overconfidence and impaired decision making. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 describes our research question and hypotheses. Section 3 explains our method for measuring the extent of compliments, praise, or flattery by analysts during earnings conference calls. Section 4 describes the data. Section 5 reports the results. Section 6 concludes. 2. HYPOTHESIS DEVELOPMENT The verbal praise by analysts on earnings conference calls is directed towards the firm’s management, whereas changes in analysts’ forecasts, stock price targets, or recommendations can occur for a multitude of reasons unrelated to management performance such as macroeconomics factors. 7 5 Prior research finds that earnings conference calls are informative (e.g., Frankel, Johnson, and Skinner 1999) and valuable to analysts (e.g., Bowen, Davis, and Matsumoto 2002; Kimbrough 2005). More recent research has used textual analysis techniques first used in other capital market settings (e.g., Antweiler and Frank 2004; Tetlock 2007; Li 2010; Loughran and McDonald 2011) to evaluate the qualitative information in earnings conference calls. For example, several studies show that earnings conference call tone provides useful information regarding current and future firm performance (e.g., Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss 2012; Brockman, Li, and Price 2015; Allee and DeAngelis 2015).8 Given the notions in prior research that earnings conference call content holds valuable information and that we can measure analysts’ sentiment through textual analysis, we seek to more closely examine the language used by analysts during earnings conference calls. Other prior research concludes that analysts use various strategies to curry favor with management. Mayew (2008) and Cohen, Lou, and Malloy (2014) find that analysts’ with more favorable stock recommendations are more likely to be called on during a firm’s earnings conference call. Chen and Matsumoto (2006) find that favorable revisions in stock recommendations improve analysts’ access to management’s private information and analysts’ forecast accuracy. Ke and Yu (2006), find that analysts who initially issue optimistic earnings forecasts and later revise to beatable earnings forecasts have higher forecast accuracy. This finding is consistent with analysts strategically altering their earnings forecasts to curry favor with management. While much of this research focuses on the pre-Regulation Fair Disclosure 8 Studies on earnings conference call attributes examine: vocal cues (Hobson, Mayew, and Venkatachalam 2012; Mayew and Venkatachalam 2012), linguistic complexity (Bushee, Gow, and Taylor 2013; Brochet, Naranjo, and Yu 2012), analyst participation (Mayew, Sharp, and Venkatachalam 2013), the absence of questions (Chen, Hollander, and Law 2015), time horizon (Brochet, Loumioti, and Serafeim 2014) and tone (Allee and DeAngelis 2015; Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss 2012; Brockman, Li, and Price 2015; Druz, Wagner, and Zeckhauser 2014; Chen, Nagar, and Schoenfeld 2014; Sinha and Huang 2014) 6 period, these concerns remain as recent research such as Brown, Call, Clement, and Sharp (2015) find that private conversations between analysts and management continue to occur in the postRegulation Fair Disclosure period. Thus, prior research suggests that analysts use their earnings forecasts and recommendations to ingratiate themselves with management. Experimental research finds that compliments, praise, and flattery fundamentally helps build relationships and can be used to curry favor (Jones 1964). If compliments by analysts are prevalent in earnings conference calls, then the verbal praise of management during earnings conference calls can be another popular means of favor seeking by analysts. While analysts can use praise as a means to curry favor with management, analysts may also avoid this behavior due to concerns that it suggests a possible conflict of interest or a lack of objectivity and professionalism. Therefore, we examine the following research question: R1: How prevalent are compliments by analysts during earnings conference calls? If analysts are unbiased in their provision of compliments during the discussion portion of earnings conference calls, then they are expressing a positive assessment of performance, likely when management has either met or exceeded certain expectations. In such cases, outcome feedback conveys information about performance outcome (Earley, Northcraft, Lee, and Lituchy 1990; Kim and Hamner 1976). When outcome feedback is presented in the form of praise or complimentary language, it is likely to signal to management and other listeners that management has engaged in a business process that generated the praise-worthy outcome. Such direct feedback related to performance can assist management in their decision making and corporate strategies (e.g., Langberg and Sivaramakrishnan 2010; Dye and Sridhar 2002). While 7 analysts can also provide feedback to managers through their earnings forecasts and recommendations, these analyst outcomes are only partly reflective of management performance and can be driven to a great extent by outside forces, such as macroeconomic factors. On the other hand, if analysts are biased in their provision of compliments during the discussion portion of earnings conference calls, then compliments may not reflect the meeting or exceeding of expectations and are not a form of useful feedback to managers. This can occur because, as mentioned earlier, analysts face incentives to curry favor with management. Thus, the relation between analysts’ compliments and current earnings news depends on the extent to which analysts are unbiased in their provision of compliments. A lack of association between analysts’ compliments and current earnings news suggests that analysts use compliments to ingratiate themselves with management, while a positive association suggests that analysts’ compliments reflect firm performance. Therefore, our first null hypothesis is: H1: There is no relation between the amount of compliments by analysts during the earnings conference call and the earnings announcement news. As previously stated, compliments can reinforce desired behavior (e.g., Manes 1983). Thus, complimentary language from unbiased analysts following the release of earnings can signal effectiveness in performance and lead to executives continuing similar behaviors, actions, and efforts that improve performance. On the other hand, if analysts are biased and use compliments to ingratiate themselves with management, then managers may undeservedly receive praise which can result in less than optimal decision making. For example, Park, Westphal, and Stern (2011) find that board members can use the flattery of management to 8 ingratiate themselves and that this can result in management overconfidence and impaired decision making. Therefore, if analysts are unbiased in their provision of compliments, then managers can learn from the analyst feedback resulting in increased future performance. If the market is less than perfectly efficient in its processing of this form of analyst feedback, then the increase in future performance can result in future positive abnormal stock returns. Thus, our second null hypothesis is: H2: There is no relation between the amount of compliments by analysts during the earnings conference call and subsequent abnormal stock returns. 3. METHOD We create a short list of complimentary phrases that analysts commonly use on earnings conference calls to describe performance. We develop our list through both the extensive reading of earnings conference call transcripts and preliminary textual analysis using the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive word list to gain a better understanding of the language that analysts typically use. Based on these two methods of identifying common complimentary phrases, we create a list of phrases where a positive adjective precedes a noun related to performance (e.g., “good quarter” or “great year”). Our list consists of all potential pairings of 18 adjectives and 10 nouns. In addition, to these pairings we include the string “congrat” in our searches to capture the words “congratulations,” “congrats,” and “congratulate,” which are commonly spoken by analysts. Our list of 18 adjectives is: great, good, excellent, nice, fantastic, remarkable, incredible, impressive, tremendous, solid, outstanding, terrific, amazing, phenomenal, strong, superb, super, and stellar. Our list of 10 nouns is: quarter, year, fiscal year, 9 job, work, execution, results, print, and number. We allow for the noun “quarter” to be preceded by the words “first”, “second,” “third,” or “fourth.” We follow the Loughran and McDonald (2011) definition of negation and do not count complimentary phrases in which one of six words (i.e., no, not, none, neither, never, or nobody) occur within the three words preceding the complimentary phrase. We also do not count the string “congrat” as a complimentary phrase if the analyst also uses the words: promotion, retirement, or birth because we find evidence of analyst’s using the string “congrat” in a nonperformance context such as in reference to a manager’s promotion, upcoming retirement, or the birth of a child. Our approach considers the context of words in the setting of earnings conference calls to a greater extent than the dictionary approach, which increases the likelihood that we are truly capturing analysts’ assessment of performance. In their survey of textual analysis, Loughran and McDonald (2014) suggest that a very small number of words will dominate frequency counts of words, which can potentially lead to spurious results. Figure 1 presents the counts of the most commonly used positive words during earnings conference calls from the Loughran and McDonald (2011) list. The word “good” is by far the most common positive word with more than 110,000 utterances by analysts in our sample. Figure 2 presents the counts of the most commonly used words by analysts immediately after the word “good.” From this we see that a substantial proportion of the time, the usage of the word “good” by analysts does not have any relation to their assessments of performance (e.g., phrases such as “good morning,” “good afternoon,” and “good evening” are quite common). Another commonly used positive word that can be used to describe performance is the word “great.” Figure 3 presents the counts of the most commonly used words by analysts immediately following the word “great.” While phrases such as “great quarter,” “great job,” and “great year” describe performance, the phrases “great 10 thanks” and “great color” do not. Thus, in the context of earnings conference calls and focusing specifically on complimentary language pertaining to firm performance, we include only phrases that are very likely to suggest positive performance or sentiment. 4. DATA We manually collect earnings conference calls from Thomson Reuters Datastream. We collect all available conference calls for any firm that was part of the S&P 500 during our January 2003 – June 2013 sample period. The sample begins in 2003 because there are a limited number of earnings conference calls prior to 2003 in Thomson Reuters Datastream. We limit our analysis to firms that appeared in the S&P 500 due to the time and costs of manually downloading our sample. By focusing on these firms, we have the largest U.S. firms which are of great interest to investors and analysts. A drawback of our sample is that the earnings conference calls on Thomson Reuters Datastream do not represent a historical database, meaning that we only obtain calls for firms that were still trading at the time of our sample collection. This is also a potential issue, depending on the research question, for various other studies using manually collected earnings conference calls. While firms that are added or dropped from the S&P 500 appear in our sample, firms that fail or are acquired do not appear in our sample. We conduct some robustness tests (described later) to assess the impact of this issue on our results, and find evidence suggesting that this is not a major driver of our results. Table 1 presents the number of earnings conference calls in our sample by year and the average of our main variable, Praise, by year. Praise measures the number of compliments on a conference call. It is the total number of compliments made by analysts on an earnings conference call scaled by the total number of words in the conference call that were spoken by 11 analysts (expressed as a percentage). Our results are not sensitive to scaling the total number of compliments by the number of analysts participating on the conference call or the number of analyst speaking parts during the conference call. We count compliments per analyst speaking part. Meaning that although the string “congrats on the great quarter” contains two of our complimentary phrases, it only counts as one compliment as the two phrases are spoken within the same analyst speaking part. Our sample contains 16,609 quarterly earnings conference calls during the January 2003 – June 2013 period. In order to ensure that a conference call is related to an earnings announcement, we require that the earnings conference call occur on the day of the earnings announcement or the following day. Our sample consists of 498 unique firms. Consistent with Praise varying with the state of the economy, there is a large decrease in the average of Praise in 2008 and 2009 relative to the other sample years. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for our sample of earnings conference calls. The positive median value for Praise (0.044%) indicates that over 50% of conference calls contain at least one analyst compliment, suggesting that analyst compliments are quite prevalent on earnings conference calls. The number of compliments on earnings conference calls (given at least one compliment) range from 1 to 21 and have a mean (median) of 2.5 (2) compliments (untabulated). These descriptive statistics provide evidence that analysts’ compliments are prevalent during earnings conference calls, answering R1. As an example, Appendix A provides excerpts from the earnings conference call containing 21 compliments. In our hypothesis testing, we control for both the tone of the overall conference call (ToneC) and the tone of the analysts’ portion of the call (ToneA) to distinguish our results from related studies that examine the tone of earnings conference calls. In multivariate regressions that include both ToneC and ToneA, the coefficient on ToneC captures the marginal effect of 12 management’s tone. ToneC is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count for the entire conference call transcript (accounting for negation), scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript. Words are classified as positive or negative using the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive and negative word lists. We select the Loughran and McDonald (2011) lists because tone measures based on that dictionary are more strongly correlated with our dependent variable of interest, Praise, and our independent variables of interest, AnnRet and ESurp. In other words, the Loughran and McDonald (2011) lists appear to produce better tone measures in the context of earnings conference calls than the Harvard General Inquirer, Diction, or Henry (2008) dictionaries. ToneA is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count spoken by analysts (accounting for negation), scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. Some prior studies scale their tone measures by the sum of the positive and negative word counts rather than by the total word count. Our results are very similar, if we use this alternate scalar for ToneA and ToneC. We winsorize the variables Praise, ToneC, ToneA, and ESurp at the 1% and 99% levels (our results are not sensitive to winsorization). We use both an earnings-based measure (ESurp) and a stock return-based measure (AnnRet) to assess the nature of the news released at the earnings announcement. ESurp is the firm’s earnings surprise relative to the mean analyst earnings forecast. AnnRet is the marketadjusted abnormal stock return over a firm’s two-day earnings announcement window, [0, +1]. The positive means and medians for AnnRet and ESurp indicate that firms in our sample, on average, release good news at their earnings announcement. This is consistent with prior literature such as the earnings announcement premium (e.g., Ball and Kothari 1991) and the walk-down to beatable analyst forecasts (e.g., Richardson, Teoh, and Wysocki 2004). The 13 average conference call transcript contains 10,500 words of which 1,500 of those words are spoken by analysts. The average firm in our sample has 9 analysts, a market capitalization of over $10 Billion, and a market-to-book ratio of about 2.75. Table 3 presents Spearman Correlations between Praise and various variables of interest. Consistent with compliments reflecting the nature of the earnings news and a rejection of H1, Table 3 indicates that the number of compliments is positively correlated with the news disclosed at the earnings announcement (AnnRet and ESurp). Praise is also significantly positively correlated with both the tone of the call (ToneC) and the tone of the analysts (ToneA). Table 3 suggests that Praise, ToneC, and ToneA are to some extent capturing related information, which is not surprising given that our list of complimentary phrases used to calculate Praise is based on some of the positive words from the Loughran and McDonald (2011) list. Although our list of complimentary phrases uses some positive words and no negative words, we find that Praise is more strongly linked with tone measures based on both positive and negative word lists, rather than tone measures based only on positive words. Our results are robust to ignoring negative words in the calculation of tone (i.e., calculating ToneC (ToneA) as the number of positive words (spoken by analysts) divided by the total number of words (spoken by analysts)). In other words, the difference in results for Praise and tone in this paper are not due to the fact that Praise reflects positive sentiment while tone is based on both positive and negative words. The significantly positive correlation between Praise and the future abnormal stock return (FutRet60) is consistent with a rejection of H2 and suggests that Praise predicts future performance. The significantly positive correlation between Praise and both the market-to-book ratio (MB) and the abnormal stock return over the prior 60 trading days (PastRet60) indicates that growth firms and firms whose stock has recently performed well generate more 14 compliments. There is also a positive correlation between Praise and the number of analysts (#Analysts), indicating that firms with more analyst following receive more compliments. There is a significantly negative relation between Praise and the word count of the call (WordCountC), which is consistent with bad news taking longer to discuss. 5. RESULTS 5.1 Praise and Concurrent News In this subsection, we test H1 by examining whether there is a relation between the amount of praise during an earnings conference call and the concurrent news after controlling for other factors including tone. We measure the concurrent earnings news in two ways, the abnormal stock return at the earnings announcement (AnnRet) and the earnings surprise (ESurp). In Table 4, we examine the relation between Praise and AnnRet. This tests the extent to which compliments are used by analysts in an unbiased manner. In the first column of Table 4, we estimate the following model (firm and time subscripts suppressed): AnnRet = β1 + β2Praise + β3ToneC + β4ToneA + β5WordCountC + β6WordCountA + β7ESurp + β8Size + β9#Analysts + β10M/B + β11PastRet60 + ε (1) We find a significantly positive relation between Praise and AnnRet. The coefficient on Praise of 9.95 suggests that a one standard deviation change in Praise is associated with a 1.34% (=9.95*0.135%) change in the abnormal earning announcement stock return. Consistent with prior literature (e.g., Brockman, Li, and Price 2015; Sinha and Huang 2014), the overall tone of the conference call (ToneC) and the tone of the analysts (ToneA) are also significantly positive. 15 However, the economic magnitudes are much smaller. A one standard deviation change in ToneC is associated with a 0.34% (=0.78*0.43%) change in AnnRet, and a one standard deviation change in ToneA is associated with a 0.24% (=0.45*0.53%) change in AnnRet. These magnitudes indicate that the association between AnnRet and Praise is more than 3.5 times stronger than the associations between AnnRet and ToneC or ToneA. Consistent with prior research the earnings announcement return is strongly associated with the earnings surprise. The announcement return is negatively associated with firm size (e.g., Chari, Jagannathan, and Ofer 1988) and the market-to-book ratio (e.g., La Porta, Lakonishok, Shleifer, and Vishny 1997). Inconsistent with a momentum (e.g., Jegadeesh and Titman 1993) or post-earnings announcement drift (Bernard and Thomas 1989) effect at the earnings announcement, PastRet60 is negatively associated with AnnRet. This is consistent with Milian (2015) which finds that in recent years prior earnings news is reversed at the following earnings announcement for easy-to-arbitrage firms (such as the S&P 500 firms examined in this study). In the second column of Table 4, we present the results with firm fixed effects included in the model. We include firm fixed effects because the amount of praise on an earnings conference call may to some extent be determined by a norm created over time rather than by the news released. Thus, by including firm fixed effects, we determine whether a firm has an abnormal amount of praise when it has an abnormal amount of news, where the normal amounts are the sample averages for each of the firms. The coefficient on Praise is slightly greater in the model that includes firm fixed effects. The coefficient on ToneC more than doubles suggesting a firm’s management has a typical tone (Davis, Ge, Matsumoto, and Zhang 2014). WordCountC and WordCountA become significant when firm fixed effects are included. The negative 16 coefficient on WordCountC indicates that calls that are longer than usual are associated with worse news than usual. The positive coefficient on WordCountA suggests that calls in which analysts speak longer than average are associated with better than average news. In Table 5, we examine the relation between Praise and ESurp. As in the previous model, this tests the extent to which compliments are used by analysts in an unbiased fashion. In the first column of Table 5, we estimate the following regression (firm and time subscripts suppressed): ESurp = β1 + β2Praise + β3ToneC + β4ToneA + β5WordCountC + β6WordCountA + β7AnnRet + β8Size + β9#Analysts + β10M/B + β11PastRet60 + ε (2) We find significantly positive coefficients on Praise and ToneC. Unlike Table 4, the statistical significance and economic magnitude of the effect is greater for ToneC compared to Praise. This is consistent with management fixating on the earnings surprise to a greater extent than the analysts, and the analysts fixating more on other news in the earnings announcement or the stock price reaction itself. This is also consistent with analysts’ compliments influencing investors and thus the concurrent stock return or analysts’ compliments predicting future revisions in analysts’ forecasts, target prices, or recommendations that occur after the earnings conference call but still within the two-day earnings announcement window. In their examination of analyst’s tone during earnings conference calls, Chen, Nagar, and Schoenfeld (2014) conclude that stock prices, at least to some extent, react to analyst’s tone. Consistent with Table 5 and prior research (e.g., Li 2008; Bloomfield 2008; Frankel, Mayew, and Sun 2010; Matsumoto, Pronk, and Roelofsen 2011), it takes managers longer to 17 discuss bad news (i.e., WordCountC is significantly negative). More analysts’ words are associated with better earnings surprises. Larger firms tend to have better earnings surprises. PastRet60 is positively associated with ESurp which is consistent with the well-established result that stock prices lead accounting earnings (e.g., Ball and Brown 1968; Kothari 2001). In column 2 of Table 5, we present the model with firm fixed effects included. Once again, as in Table 4, the coefficient on ToneC more than doubles indicating that managers have a typical tone. The coefficient on Praise does not change much and the coefficient on ToneA remains insignificant. Overall the results in this subsection indicate that Praise is strongly associated with the announced news. This suggests that analysts are not, on average, indiscriminately showering compliments upon management. Analysts are selective, on average, in their use of compliments. This suggests that praise is not merely an attempt to curry favor with management. This effect is much greater when news is measured as the abnormal announcement return compared to the earnings surprise. This potentially indicates that analysts can discriminate to some extent when an earnings surprise is truly good news. This is interesting because positive earnings surprises frequently do not result in a positive announcement return. For example, Kinney, Burgstahler, and Martin (2002) find that the earnings surprise and announcement return differ in sign about 45% of the time. 5.2 Praise and Future Stock Returns In this subsection, we test H2 by testing whether there is a relation between the amount of praise during an earnings conference call and future stock returns. 18 In Table 6, we examine the relation between Praise and abnormal stock returns over the subsequent 60 trading days (FutRet60). This tests whether there is value to investors in tracking the amount of praise by analysts on earnings conference calls. In the first three columns of Table 6, we estimate variations of the following model and in the fourth column we estimate the following model (firm and time subscripts suppressed): FutRet60 = β1 + β2Praise + β3ToneC + β4ToneA + β5WordCountC + β6WordCountA + β7AnnRet + β8Size + β9#Analysts + β10M/B + β11PastRet60 + β12LagPraise + β13LagToneC + β14LagToneA + β14LagWordCountC + β15LagWordCountA + ε (3) In testing H2, we are interested in predicting future stock returns, thus it is inappropriate to use firm fixed effects in the model. Firm fixed effects imparts a look-ahead bias because we don’t know the sample mean of the variables until the end of the sample period. Thus, rather than including firm fixed effects, we include lagged values (from the firm’s previous earnings conference call) for our variables related to compliments, tone, and word counts. Consistent with Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss (2012), in column 1 there is a significantly positive coefficient on ToneC. To assess the economic magnitude, a two standard deviation change in ToneC is associated with a 0.65% change in FutRet60. This drift is modest in comparison to the magnitude in Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss (2012). This is likely due to the fact that our sample consists of S&P 500 firms which are larger and likely more efficiently priced than the firms from Price, Doran, Peterson, and Bliss (2012) which intentionally sample across firms of varying sizes. AnnRet and ESurp are insignificant in all four columns, indicating no evidence of a post-earnings announcement drift in this sample of S&P 500 firms. Size is 19 significantly negative in all four columns, suggesting that smaller firms have higher stock returns in this sample. In column 2, the coefficient of 3.17 on Praise indicates that a two standard deviation change in Praise is associated with a 0.86% change in FutRet60. As mentioned above, the drift is potentially larger for smaller firms that hold earnings conference calls. In column 3, ToneA is insignificant suggesting that analyst tone is not useful in predicting future returns. In column 4, all three variables, Praise, ToneC, and ToneA (along with their lagged values) are included in the regression. Praise is statistically significant, while both ToneC and ToneA are not. Together with the result in column 1, this suggests that Praise subsumes any predictability in the overall tone of the call. In an untabulated robustness test, Praise remains statistically significant when future abnormal stock returns are measured over the subsequent 30 or 45 trading days rather than 60. To consider whether analysts’ compliments preempt their forecast revisions (this is analogous to the idea in Chen, Nagar, and Schoenfeld (2014) that tone reflects analysts’ real-time belief revisions), in untabulated results we find that the coefficient on Praise remains statistically significant after adding the mean analyst earnings forecast revision in the week following the earnings conference call as an additional control variable to the regressions in columns 2 and 4 of Table 6. We also do not find in untabulated analyses that the subsequent drift in stock prices is concentrated in the days immediately following the earnings conference call, which is the most common time for analysts to revise their forecasts (e.g., Ivkovic and Jegadeesh 2004). These two robustness tests suggest that the future abnormal returns predicted by Praise are not due analysts’ compliments preempting their forecast revisions. Although we cannot conclude that analysts’ compliments cause managers to continue their praise-worthy behavior, this result is 20 consistent with analysts’ compliments potentially being a valuable form of feedback to managers. Regardless of the exact mechanism, the results suggest that there is value to investors in tracking the extent of analyst praise on earnings conference calls. In the fifth column of Table 6, we include a new variable, OverstatedPraise, in place of Praise, ToneC, and ToneA. OverstatedPraise is the count of the 18 adjectives from our complimentary phrase list (spoken by analysts), scaled by the total number of words spoken by analysts. The coefficient on OverstatedPraise is insignificant, most likely due to the high frequency of meaningless phrases such as “good morning” (recall Figure 2). This provides further evidence that careful parsing is required by researchers and investors. To address the fact that our sample does not represent a historical database of earnings conference calls, we repeat the analyses from Tables 4, 5, and 6, solely on firms that were in the S&P 500 at the start of our sample period. This addresses the concern that firms that were later added to the S&P 500 had strong prior performance. Our results are robust to this alternate sample (untabulated). We also repeat this robustness test on the first half of our sample period. This reduces the amount of time for poor performers to fail or get acquired. Again, we find that our results are robust (untabulated). These robustness tests cannot completely rule out survivorship bias, but are consistent with our results and provide some comfort that our results are not being driven by this issue. 6. CONCLUSION We set out to familiarize ourselves with the actual context of the words used by analysts on earnings conference calls by examining 16,609 conference calls of S&P 500 companies. We find that analysts’ complimentary phrases during the discussion segment of earnings conference 21 calls are prevalent and reflective of the earnings announcement news. The number of compliments predicts future stock returns. Identifying complimentary phrases such as “great year” and “good quarter” narrows the focus, and allows researchers and investors to more directly capture the sentiment of analysts and the feedback received by management. We are unsure of the exact mechanism for which compliments predict future stock returns. Thus, future research can look more closely at the impact of compliments on investors’ decisions and on managers’ decisions. Additionally, future research on analysts currying favor with management can gain from an understanding of individual analyst’s characteristics and their propensity to praise management during earnings conference calls. 22 REFERENCES Allee, K. D. and M. D. DeAngelis. “The Structure of Voluntary Disclosure Narratives: Evidence from Tone Dispersion.” Journal of Accounting Research, (forthcoming). Antweiler, W. and M. Z. Frank. “Is All That Talk Just Noise? The Information Content of Internet Stock Message Boards.” Journal of Finance, 59, (2004), pp. 1259-1294. Ball, R. and P. Brown. “An Empirical Evaluation of Accounting Income Numbers.” Journal of Accounting Research, 6, (1968), pp. 159-177. Ball, R. and S. P. Kothari. “Security Returns Around Earnings Announcements.” The Accounting Review, 66, (1991), pp. 718-738. Bernard, V. L. and J. K. Thomas. “Post-earnings Announcement Drift: Delayed Price Response or Risk Premium.” Journal of Accounting Research, 27, (1989), pp. 1-36. Bloomfield, R. “Discussion of Annual Report Readability, Current Earnings, and Earnings Persistence.” Journal of Accounting & Economics, 45, (2008), pp. 248-252. Bowen, R. M., A. K. Davis, and D. A. Matsumoto. “Do Conference Calls Affect Analysts’ Forecasts?” The Accounting Review, 77, (2002), pp. 285-316. Brochet, F., M. Loumioti, and G. Serafeim. “Speaking of the Short-term: Disclosure Horizon and Capital Market Outcomes.” Working Paper, Boston University (2014). Brochet, F., P. L. Naranjo, and G. Yu. “Capital Market Consequences of Linguistic Complexity in Conference Calls of Non-U.S. Firms.” Working Paper, Boston University (2013). Brockman, P., X. Li, and S. M. Price. “Differences in Conference Call Tones: Managers versus Analysts.” Financial Analysts Journal, (forthcoming). Brown, L. D., A. C. Call, M. B. Clement, and N. Y. Sharp. “Inside the “Black Box” of Sell-side Financial Analysts.” Journal of Accounting Research, 53, (2015), pp. 1-47. Bushee, B. J., I. D. Gow, and D. J. Taylor. “Linguistic Complexity in Firm Disclosures: Obfuscation or information?” Working Paper, University of Pennsylvania (2013). Chari, V. V., R. Jagannathan, and A. R. Ofer. “Seasonalities in Security Returns: The Case of Earnings Announcements.” Journal of Financial Economics, 21, (1988), pp. 101-121. Chen, S., S. Hollander, and K. Law. “The Price of Silence: When No One Asks Questions during Conference Calls.” Working Paper, University of Texas at Austin (2015). 23 Chen, S. and D. A. Matsumoto. “Favorable versus Unfavorable Recommendations: The Impact on Analyst Access to Management-provided Information.” Journal of Accounting Research, 44, (2006), pp. 657-689. Chen, J. V., V. Nagar, and J. Schoenfeld. “Sources of Analyst Expertise.” Working Paper, University of Michigan (2014). Cohen, L., D. Lou, and C. Malloy. “Playing Favorites: How Firms Prevent the Revelation of Bad News.” Working Paper, Harvard University (2014). Davis, A. K., W. Ge, D. Matsumoto, and J. L. Zhang. “The Effect of Manager-specific Optimism on the Tone of Earnings Conference Calls.” Review of Accounting Studies, (forthcoming). Dye, R. A. and S. S. Sridhar. ‘Resource Allocation Effects of Price Reactions to Disclosures.” Contemporary Accounting Research, 19, (2002), pp. 385-410. Druz, M., A. F. Wagner, and R. J. Zeckhauser. “How Analysts and the Market Read between the Lines of Conference Calls.” Working Paper, Harvard University (2014). Earley, P. C., G. B. Northcraft, C. Lee, and T. R. Lituchy. Impact of process and outcome feedback on the relation of goal setting to task performance. Academy of Management Journal, 33, (1990), pp. 87-105. Frankel, R., M. Johnson, and D. J. Skinner. “An Examination of Conference Calls as a Voluntary Disclosure Medium.” Journal of Accounting Research, 37, (1999), pp. 133-150. Frankel, R., W. J. Mayew, and Y. Sun. “Do Pennies Matter? Investor Relations Consequences of Small Negative Earnings Surprises.” Review of Accounting Studies, 15, (2010), pp. 220242. Henry, E. “Are Investors Influenced by How Earnings Press Releases are Written?” The Journal of Business Communication, 45, (2008), pp. 363-407. Hobson, J. L., W. J. Mayew, and M. Venkatachalam. “Analyzing Speech to Detect Financial Misreporting.” Journal of Accounting Research, 50, (2012), pp. 349-392. Ivkovic, Z. and N. Jegadeesh. “The Timing and Value of Forecast and Recommendation Revisions.” Journal of Financial Economics, 73, (2004), pp. 433-463. Jegadeesh, N. and S. Titman. “Returns to Buying Winners and Selling Losers: Implications for Stock Market Efficiency.” Journal of Finance, 48, (1993), pp. 65-91. Jones, E. E. Ingratiation, a social psychological analysis. Meredith Publishing, (1964), New York. 24 Ke, B. and Y. Yu. “The Effect of Issuing Biased Earnings Forecasts on Analysts’ Access to Management and Survival.” Journal of Accounting Research, 44, (2006), pp. 965-999. Kim, J. S. and W. C. Hamner. “Effect of Performance Feedback and Goal Setting on Productivity and Satisfaction in an Organizational Setting.” Journal of Applied Psychology, 61, (1976), pp. 48-57. Kimbrough, M. D. “The Effect of Conference Calls on Analyst and Market Underreaction to Earnings Announcements.” The Accounting Review, 80, (2005), pp. 189-219. Kinney, W., D. Burgstahler, and R. Martin. “Earnings Surprise “Materiality” as Measured by Stock Returns.” Journal of Accounting Research, 40, (2002), pp. 1297-1329. Kothari, S. P. “Capital Markets Research in Accounting.” Journal of Accounting & Economics, 31, (2001), pp. 105-231. La Porta, R., J. Lakonishok, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. “Good News for Value Stocks: Further Evidence on Market Efficiency.” Journal of Finance, 52, (1997), pp. 859-874. Langberg, N. and K. Sivaramakrishnan. “Voluntary Disclosures and Analyst Feedback.” Journal of Accounting Research, 48, (2010), pp. 603-646. Li, F. “Annual Report Readability, Current Earnings, and Earnings Persistence.” Journal of Accounting & Economics, 45, (2008), pp. 221-247. Li, F. “The Information Content of Forward-looking Statements in Corporate Filings: A Naïve Bayesian Machine Learning Approach.” Journal of Accounting Research, 48, (2010), pp. 1049-1102. Loughran, T. and B. McDonald. “When is a Liability Not a Liability? Textual Analysis, Dictionaries, and 10-Ks.” Journal of Finance, 66, (2011), pp. 35-65. Loughran, T. and B. McDonald. “Textual Analysis in Finance and Accounting: A Survey.” Working Paper, University of Notre Dame (2014). Loughran, T. and B. McDonald. “The Use of Word Lists in Textual Analysis.” Journal of Behavioral Finance, 16, (2015), pp. 1-11. Manes, J. Compliments: A mirror of cultural values. Sociolinguistics and Language Acquisition, Newbury House, (1983), Rowley, MA. Matsumoto, D., M. Pronk, and E. Roelofsen. “What Makes Conference Calls Useful? The Information Content of Managers’ Presentations and Analysts’ Discussion Sessions.” The Accounting Review, 86, (2011), pp. 1383-1414. 25 Mayew, W. J. “Evidence of Management Discrimination among Analysts during Earnings Conference Calls.” Journal of Accounting Research, 46, (2008), pp. 627-659. Mayew, W. J. and M. Venkatachalam. “The Power of Voice: Managerial Affective States and Future Firm Performance.” Journal of Finance, 67, (2012), pp. 1-43. Milian, J. A. “Unsophisticated Arbitrageurs and Market Efficiency: Overreacting to a History of Underreaction.” Journal of Accounting Research, 53, (2015), pp.175-220. Park, S. H., J. D. Westphal, and I. Stern. “Set up for a Fall: The Insidious Effects of Flattery and Opinion Conformity toward Corporate Leaders.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 56, (2011), pp. 257-302. Price, S. M., J. S. Doran, D. R. Peterson, and B. A. Bliss. “Earnings Conference Calls and Stock Returns: The Incremental Informativeness of Textual Tone.” Journal of Banking & Finance, 36, (2012), pp. 992-1011. Richardson, S., S. H. Teoh, and P. D. Wysocki. “The Walk-down to Beatable Analyst Forecasts: The Role of Equity Issuance and Insider Trading Incentives.” Contemporary Accounting Research, 21, (2004), pp. 885-924. Sinha, P. and X. Huang. “The Role of Financial Analysts’ Tone in Interpreting Management Disclosure Tone in Conference Calls.” Working Paper, California State University, Long Beach (2014). Tetlock, P. C. “Giving Content to Investor Sentiment: The Role of Media in the Stock Market.” Journal of Finance, 62, (2007), pp. 1139-1168. 26 Appendix A Example of Analysts’ Praise during an Earnings Conference Call Compliment # 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Analyst Greenberger Andreeva Black Meyer Tennant Chen Panella Murchison Pierce Wyckoff Kallik Kallik Telsey Greenberger Kloppenburg Shapiro Jaffe Kloppenburg Guthrie Chen Black Excerpt Great. Thank you. Good morning, and congratulations to everyone on a fantastic quarter. … My question is on the Urban division. Congratulations, very nice improvement there. Could you … Thanks and I will add my congratulations. I guess … Thank you. Let me add my congratulations on a terrific quarter. I just had a question on the … Good morning. Let me add my congratulations, truly a spectacular quarter. My question is … Thank you. Congratulations on an amazing quarter everyone. Hey, good morning, and congratulations to all of you. John, just wanted to get an update on … Thank you very much. Congratulations. Let me piggy back off of Adrienne's question … Thank you, and I'll add my congratulations. Ted I have a question for you about … Hi everyone. Great job. Good morning, and congratulations, as well. Congratulations and good luck. Good morning, everyone. Congratulations. Glen, can you talk about … … how you think about anniversarying those really strong numbers last year? What are the strategies … Good morning. Congratulations to everyone. Glen, I heard you talk about … Hey, guys. Congratulations. Thanks, very much, guys. My congratulations as well. Very strong results. I guess a question … I am so sorry. Hi. Congratulations to you all. Glen, what I was trying to ask is … Thank you, and congratulations. Glen, you called out accessories as being a big part of … Thank you. I will add my congratulations as well. I was wondering, Glen, if you can … Let me add my congratulations as well. You mentioned in your prepared remarks that … This table presents the analysts’ compliments from the Urban Outfitters’ earnings conference call for Q1 2009 which was held on May 15, 2008. This earnings conference call contained 21 analyst compliments, the most in our sample. This table provides the last name of the analyst speaking and an excerpt from their speaking part that contained a complimentary phrase from our list. The complimentary phrases from our list are bolded and italicized. 27 Figure 1 – Most Common Positive Words Spoken by Analysts positive benefit opportunity improvement strong great gain better able good 0 20,000 40,000 60,000 80,000 100,000 120,000 140,000 This figure depicts the counts of the most commonly spoken positive words by analysts in our sample of earnings conference calls. Positive words are defined as words appearing in the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive word list. 28 Figure 2 – Most Common Words Spoken by Analysts after the Word “Good” number run about to job evening quarter luck afternoon morning 0 10,000 20,000 30,000 40,000 50,000 60,000 70,000 80,000 This figure depicts the counts of the most commonly spoken words by analysts immediately after the word “good” in our sample of earnings conference calls. 29 Figure 3 – Most Common Words Spoken by Analysts after the Word “Great” deal thank results thanks year color to and job quarter 0 500 1,000 1,500 2,000 2,500 3,000 3,500 4,000 This figure depicts the counts of the most commonly spoken words by analysts immediately after the word “great” in our sample of earnings conference calls. 30 Table 1 Sample of Earnings Conference Calls and Average Praise by Year Year Number of Earnings Conference Calls Praise 2003 1,286 0.103% 2004 1,402 0.110% 2005 1,443 0.095% 2006 1,485 0.108% 2007 1,581 0.093% 2008 1,674 0.076% 2009 1,663 0.068% 2010 1,715 0.095% 2011 1,725 0.085% 2012 1,733 0.087% 2013 902 0.086% Total 16,609 0.091% This table presents the number of earnings conference calls in the sample by year and the average value of Praise by year. Praise is the total number of compliments made by analysts on a conference call, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts (expressed as a percentage). Earnings conference call transcripts were manually downloaded from Thomson Reuters Datastream. Earnings conference calls transcripts were downloaded for firms that were members of the S&P 500 at some point during our, January 2003 through June 2013, sample period. The sample consists solely of earnings conference calls that occur on the day of the earnings announcement or the following day. 31 Table 2 Descriptive Statistics Variable N Mean Std. Dev. 25th Median 75th Praise 16,609 0.091% 0.135% 0 0.044% 0.135% AnnRet 16,609 0.26% 6.39% -2.86% 0.09% 3.29% ESurp 16,609 0.059% 0.444% -0.014% 0.049% 0.162% FutRet60 16,609 1.27% 13.11% -5.58% 0.66% 7.15% ToneC 16,609 0.43% 0.43% 0.15% 0.42% 0.71% ToneA 16,609 0.064% 0.53% -0.278% 0.063% 0.401% WordCountC 16,609 10.5 2.3 9.2 10.4 11.6 WordCountA 16,609 1.5 0.6 1.1 1.4 1.8 #Analysts 16,609 9.4 5.3 5 9 13 Size 16,609 23.07 1.15 22.30 22.99 23.72 MB 16,609 1.02 0.78 0.53 0.99 1.45 PastRet60 16,609 1.46% 13.20% -5.62% 0.84% 7.52% This table presents descriptive statistics for our sample of earnings conference calls. Praise is the total number of compliments made by analysts on a conference call, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. AnnRet is the firm’s abnormal stock return at the time of the earnings announcement with a concurrent earnings conference call. It is the return on the firm’s stock less the return on the CRSP valueweighted index over the two-day window, [0, +1], where day 0 is the earnings announcement date, after adjusting for after-hours earnings announcements. Concurrent earnings conference calls are defined as earnings conference calls that occur on day 0 or day +1. ESurp is the firm’s current earnings surprise. It is the difference between the announced earnings and the average analyst forecast, scaled by the firm’s stock price prior to the current earnings announcement. FutRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the 60 trading days following the earnings announcement, beginning on day +2. ToneC is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count for the entire conference call transcript, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript. Words are classified as positive or negative using the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive and negative word lists. ToneA is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count spoken by analysts, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. WordCountC is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript. WordCountA is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. #Analysts is the number of analysts providing an earnings forecast for the earnings conference call quarter in IBES. Size is the natural logarithm of the firm’s market capitalization on the day prior to the earnings announcement. MB is the natural logarithm of the market-to-book ratio prior to the earnings announcement. PastRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the previous 60 trading days, [-60, -1]. Praise, AnnRet, ESurp, FutRet60, ToneC, ToneA, and PastRet60 are expressed as percentages. 32 Table 3 Spearman Correlations Variable Praise AnnRet 0.27*** ESurp 0.24*** FutRet60 0.03*** ToneC 0.25*** ToneA 0.27*** WordCountC -0.02*** WordCountA -0.01 #Analysts 0.04*** Size -0.06*** MB 0.18*** PastRet60 0.13*** This table presents the Spearman correlations for our sample of earnings conference calls. Praise is the total number of compliments made by analysts on a conference call scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. AnnRet is the firm’s abnormal stock return at the time of the earnings announcement with a concurrent earnings conference call. It is the return on the firm’s stock less the return on the CRSP valueweighted index over the two-day window, [0, +1], where day 0 is the earnings announcement date, after adjusting dates for after-hours earnings announcements. Concurrent earnings conference calls are defined as earnings conference calls that occur on day 0 or day +1. ESurp is the firm’s current earnings surprise. It is the difference between the announced earnings and the average analyst forecast, scaled by the firm’s stock price prior to the current earnings announcement. FutRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted future stock return over the 60 trading days following the earnings announcement, beginning on day +2. ToneC is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count for the entire conference call transcript, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript. Words are classified as positive or negative using the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive and negative word lists. ToneA is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count spoken by analysts, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. WordCountC is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript. WordCountA is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. #Analysts is the number of analysts providing an earnings forecast for the announced quarter in IBES. Size is the natural logarithm of the firm’s market capitalization on the day prior to the earnings announcement. MB is the natural logarithm of the market-to-book ratio prior to the earnings announcement. PastRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the previous 60 trading days, [-60, -1]. 33 Table 4 Relation between Praise and Earnings Announcement Returns (1) (2) Praise 9.95*** [17.61] 11.71*** [19.28] ToneC 0.78*** [4.81] 1.69*** [5.82] ToneA 0.45*** [3.82] 0.51*** [4.29] WordCountC -0.04 [-1.15] -0.10*** [-2.62] WordCountA 0.06 [0.45] 0.49*** [3.56] ESurp 3.06*** [12.48] 3.06*** [12.03] Size -0.20*** [-2.80] -1.26*** [-5.31] #Analysts -0.007 [-0.62] 0.006 [0.47] MB -0.38*** [-3.39] -1.07*** [-5.31] PastRet60 -0.029*** [-4.49] -0.025*** [-3.97] NO YES YES YES 11.74% 16,609 17.12% 16,609 Firm Fixed Effects Year Fixed Effects R2 N This table presents the results of two regressions with AnnRet as the dependent variable. The regression in the second (first) column does (not) include firm fixed effects. AnnRet is the firm’s abnormal stock return at the time of the earnings announcement with a concurrent conference call. It is the return on the firm’s stock less the return on the CRSP value-weighted index over the two-day window, [0, +1], where day 0 is the earnings announcement date, after adjusting dates for after-hours earnings announcements. Praise is the total number of compliments made by analysts on a conference call scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. ToneC is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count for the entire conference call transcript, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript. Words are classified as positive or negative using the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive and negative word lists. ToneA is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count spoken by analysts, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. WordCountC is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript. WordCountA is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. ESurp is the firm’s current earnings surprise. It is the difference between the announced earnings and the average analyst forecast, scaled by the firm’s stock price prior to the current earnings announcement. Size is the natural logarithm of the firm’s market capitalization on the day prior to the earnings announcement. #Analysts is the number of analysts providing an earnings forecast for the announced quarter in IBES. MB is the natural logarithm of the market-to-book ratio prior to the earnings announcement. PastRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the previous 60 trading days, [-60, -1]. Standard errors are clustered on two dimensions, quarter and firm. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. Table 5 Relation between Praise and Earnings Surprises (1) (2) Praise 0.167*** [4.24] 0.183*** [4.38] ToneC 0.073*** [4.32] 0.160*** [7.27] ToneA 0.008 [1.07] -0.002 [-0.28] WordCountC -0.006** [-2.27] -0.008** [-2.17] WordCountA 0.023** [2.26] 0.023** [2.00] AnnRet 0.015*** [11.00] 0.015*** [10.53] Size 0.017*** [2.70] -0.001 [-0.03] #Analysts -0.001 [-0.46] 0.001 [1.10] MB 0.01 [0.56] 0.07*** [3.07] 0.003*** [4.25] 0.003*** [3.62] NO YES YES YES PastRet60 Firm Fixed Effects Year Fixed Effects R2 9.23% 17.73% N 16,609 16,609 This table presents the results of two regressions with ESurp as the dependent variable. The regression in the second (first) column does (not) include firm fixed effects. ESurp is the firm’s current earnings surprise. It is the difference between the announced earnings and the average analyst forecast, scaled by the firm’s stock price prior to the current earnings announcement. Praise is the total number of compliments made by analysts on a conference call scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. ToneC is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count for the entire conference call transcript, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript. Words are classified as positive or negative using the Loughran and McDonald (2011) positive and negative word lists. ToneA is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count spoken by analysts, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. WordCountC is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript. WordCountA is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. AnnRet is the firm’s abnormal stock return at the time of the earnings announcement with a concurrent conference call. It is the return on the firm’s stock less the return on the CRSP value-weighted index over the two-day window, [0, +1], where day 0 is the earnings announcement date, after adjusting dates for after-hours earnings announcements. Size is the natural logarithm of the firm’s market capitalization on the day prior to the earnings announcement. #Analysts is the number of analysts providing an earnings forecast for the announced quarter in IBES. MB is the natural logarithm of the market-to-book ratio prior to the earnings announcement. PastRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the previous 60 trading days, [-60, -1]. Standard errors are clustered on two dimensions, quarter and firm. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. 35 Table 6 Relation between Praise and Future Stock Returns (1) (2) (3) 3.17*** [2.68] Praise ToneC (4) 3.20*** [2.78] 0.76* [1.93] 0.46 [0.99] ToneA 0.26 [0.75] 0.04 [0.12] OverstatedPraise WordCountC (5) 0.03 [0.11] 0.06 [0.76] WordCountA 0.06 [0.67] 0.07 [0.84] 0.06 [0.69] 0.06 [0.71] -0.01 [-0.06] -0.09 [-0.36] 0.02 [0.08] -0.07 [-0.27] AnnRet 0.008 [0.18] -0.002 [-0.05] 0.010 [0.21] -0.007 [-0.14] 0.013 [0.27] ESurp 0.10 [0.12] 0.08 [0.09] 0.15 [0.18] 0.09 [0.11] 0.13 [0.16] Size -1.19*** [-4.12] -1.18*** [-3.92] -1.21*** [-3.98] -1.17*** [-4.04] -1.21*** [-4.03] #Analysts -0.02 [-0.58] -0.02 [-0.73] -0.02 [-0.50] -0.02 [-0.60] -0.02 [-0.59] MB -0.67 [-1.24] -0.76 [-1.29] -0.66 [-1.20] -0.70 [-1.32] -0.70 [-1.19] PastRet60 0.01 [0.53] 0.01 [0.49] 0.02 [0.57] 0.01 [0.43] 0.02 [0.60] -1.56* [-1.67] LagPraise LagToneC -0.71 [-0.72] -1.07** [-2.56] -0.57 [-1.29] -0.79** [-2.32] LagToneA -0.69** [-2.09] LagOverstatedPraise LagWordCountC LagWordCountA -0.40 [-1.03] 0.019 [0.24] 0.004 [0.05] -0.016 [-0.19] -0.001 [-0.01] -0.001 [-0.01] 0.18 [0.61] 0.19 [0.64] 0.11 [0.36] 0.15 [0.50] R2 1.55% 1.58% 1.59% 1.69% 1.53% N 16,609 16,609 16,609 16,609 16,609 This table presents the results of four regressions with FutRet60 as the dependent variable. FutRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the 60 trading days following the earnings announcement, beginning on day +2. Praise is the total number of compliments made by analysts on a conference call scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. ToneC is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count for the entire conference call transcript, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript. ToneA is the difference between the positive word count and the negative word count spoken by analysts, scaled by the total number of words in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. OverstatedPraise is the count of the 18 adjectives from our complimentary phrase list spoken by analysts, scaled by the total number of words spoken by analysts. WordCountC is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript. WordCountA is the total number of words (in thousands) in the conference call transcript that were spoken by analysts. AnnRet is the firm’s abnormal stock return at the time of the earnings announcement with a concurrent conference call. ESurp is the firm’s current earnings surprise. Size is the natural logarithm of the firm’s market capitalization on the day prior to the earnings announcement. #Analysts is the number of analysts providing an earnings forecast for the announced quarter in IBES. MB is the natural logarithm of the market-to-book ratio prior to the earnings announcement. PastRet60 is the firm’s market adjusted stock return over the previous 60 trading days, [-60, -1]. LagPraise, LagToneC, LagToneA, LagOverstatedPraise, LagWordCountC, and LagWordCountA are the values for Praise, ToneC, ToneA, WordCountC, and WordCountA from the firm’s previous earnings conference call, respectively. Standard errors are clustered on two dimensions, quarter and firm. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively. 36