Children's Health or Corporate Wealth?

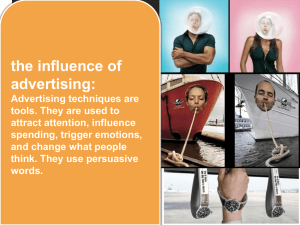

advertisement