Sander van der Leeuw School of Sustainability Arizona State

advertisement

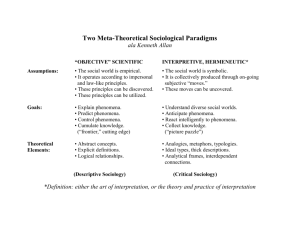

SUSTAINABILITY AND FUTURE QUALITY OF LIFE: A DISCUSSION PAPER1 Sander van der Leeuw School of Sustainability Arizona State University Abstract In most of the sustainability debate, the discussions refer to the past much more specifically than to the future. Collectively, we seem to select things from our current lifestyle that we’d like to keep, others which we think we might do without, or yet others for which we expect to find the substitute technologies that allow us to maintain our comforts while mitigating their impact. But the predominant tendency has been to focus on those things that we don’t want for our future: resource scarcity, lower comfort levels, destruction of ecosystem services or increases in air pollution or waste. On the other hand, there is relatively little positive reflection or discussion on “What kind of future do we want?” which starts from first principles and/or is detached enough from the past or the present to draw a ‘Gestalt’ of that future. Given this situation, the first question to ask is, of course, “Why would this be so?” Digging a little deeper, I raise the question: “Does our intellectual tradition, and in particular our scientific tradition, have anything to do with that?” I argue that that is indeed the case – that our reductionist scientific tradition, together with the institutional framework (universities, career structures, etc.) that underpins it (and which is only slowly being replaced), has handicapped us in thinking freely about the future. In particular, it has emphasized thinking about “origins” rather than “emergence”, about “feedback” rather than “feed-forward”, about “learning from the past” rather than “anticipating the future”. Next, one cannot but wonder whether this bias in favor of an “a posteriori” or “ex-post” perspective as opposed to an “a priori” or “ex ante” point of view is, or is not, part of the way our cognition works. Atlan (1992) seems to argue in favor of that thesis when he proposes that our theories are underdetermined by our observations. If that is so, then the logical conclusion would be that our theories are over-determined by prior experience. But that may not be the last word on this issue, and in the paper I will delve deeper into it. Can we change the way we are thinking about the future? Many individuals, from classical Greek philosophers to 18th and 19th century science-fiction authors, have either been able to design utopias or to extrapolate positively from their lifetime observations into the future. Inventors have also been able to anticipate, and most of us call on our “intuition” when we need to anticipate. The question is thus raised whether it could possibly be the case that, at the individual level, many people have the capacity to think about the future, but that the capability to communicate such thinking is rare? If the latter is the case, then our next question is: “Is communication about the future difficult per se, or is it rendered (more) difficult because we do not train this capacity in our education?” Or even more critically: “Is our capacity to anticipate in some way diminished by our education?” Here we touch on what I deem to be one of the most critical issues for our society in the current predicament – the fact that most education in our societies is focused on causally understanding the past, rather than creatively promoting reasoned and testable creative thinking about the future. What would be needed to change that? Preface If I have gratefully accepted the invitation of the organizers to attend this symposium, it is because I have for some time been looking for an occasion to present to a wider, non-specialist audience some ideas that have been bouncing around in my head. Very eclectic, idiosyncratic and therefore also very tentative ideas that have emerged in the margins of forty years spent looking at the long-term evolution of societies and their environments from an environmental, a social and a technological point of view. 1 As this is a discussion paper, please do not cite or otherwise refer to it or its content unless you have written agreement from the author Evidently, it will not be possible, in the space and time allotted to me here, to go very deeply into many of the arguments that underpin these ideas. But that, to me, is of less importance that to have the occasion to bring all of this together in one narrative, and to test out how that narrative comes across. Some of its elements have been elaborated in earlier papers that I will refer the reader to; others are borrowed or adapted from authors in different disciplines – in effect many of you will probably say ‘didn’t you know this or that paper or book, or even this or that ‘school’, in one or more disciplines?’ because I did not refer to it. That is where the fact that I have not grown up in any of your disciplines is both an advantage and a handicap. Practicing trans-disciplinary scholarship is after all “the art of constructively disappointing the practitioners of all disciplines”. Introduction: Sustainability is a societal, rather than an environmental, issue In one of his less well-known movies, the director Leonardo Di Caprio raises a fundamental issue in an implicit comment on Albert Gore’s “The Inconvenient Truth”. If we don’t manage to deal with the current issues, so Di Caprio’s argument goes, the environment will not be the one to suffer – it will survive long after our societies have disappeared. By implication, sustainability is about the survival of our societies rather than the survival of the environment. “Nature” and “Environment” are concepts invented by people, in our own western intellectual tradition. The separation between the ‘natural’ world (the world ‘out there’) and the ‘human’ realm (‘our world’) finds its origins, at least according to some historians, in the 14th Century (cf. Evernden, 1992). But whatever the origins may be, one can clearly follow, in the 17th to 19th centuries the ‘game of mirrors’ that leads to the development of the modern sciences by studying the interaction between ‘Natural History’ on the one hand, and the history of society (commonly called ‘History’) on the other (van der Leeuw, 1998). Around the same time – and under the impact of the formalization of academic research, teaching, and career specialization in universities – we see a ‘hardening’ of academic disciplines, in which the initially epistemological relationships between phenomena and ideas (different observations leading to different vocabularies, techniques, methods and theories) were given the status of ontological relationships, so that the ideas (methods, techniques, etc.) current in the different specialist communities (‘disciplines’) came to prevail over the observations, increasingly determining the nature of the questions asked, the character of the observations made, etc. (see Figure 1).2 As a result, these ‘disciplines’ increasingly grew apart, were practiced by different communities, each with their own specific language, customs, methods, techniques and institutions, and communicating less and less with each other. Ultimately, this led to the current predicament that it is increasingly necessary, but simultaneously increasingly difficult, to achieve intellectual fusion between ideas current in different academic disciplines (‘trans-disciplinarity’), so as to regain the ‘holistic’ perspective that is necessary to deal with today’s challenges in the interactions between our societies and their environments. Recent years have seen a growing awareness of the fact that separating the natural from the social in studying these interactions is counter-productive. In the words of McGlade (1995) 2 One might thus say that academic ‘disciplines’ emerged out of the self-imposed discipline developed by the different communities emerging around the study of different kinds of phenomena to ask commonly agreed kinds of questions, use agreed methods and techniques, make agreed kinds of observations and use those to falsify, verify, extend or detail agreed theories, etc. “There is no natural (sub-) system, there is no social (sub-) system, there are only socio-natural interactions”. Hence the prevalence of ‘hybrid’ terms such as ‘Socio-Environmental Systems’ (SES) and the like. But in attempts to study this domain, it is all too often – and wrongly – assumed that the interactions between societies and their environments are symmetrical. In the words of Niklas Luhmann (1986): “Humans do not communicate with the environment – they REALM OF CONCEPTS Cultural sphere: people's perceptions, norms and ideas ontological connection epistemological connection REALM OF CONCEPTS Natural sphere: Potential resources Socionatural dynamics and their results (e.g. landscape) REALM OF PHENOMENA Cultural disciplines, social sciences and humanities ontological connection epistemological connection Natural and life sciences Cultural and social phenomena Natural phenomena REALM OF PHENOMENA Figure 1: Epistemological links become ontological ones as academic research is institutionalized into disciplines. In the process, shared ideas come to direct research. communicate about the environment among themselves, by means of concepts that are selfreferentially defined.” In effect, humans define what they consider ‘their environment’; they identify its challenges and the threats to it, and, to top it all off, they define the ways to deal with environmental problems. This means two things: (1) that the only ones who can actually do something about our environmental problems, and strive for sustainability, are we ourselves, our societies, our institutions, and (2) that striving for sustainability is not about protecting the environment, but about preserving the conditions we currently deem necessary for our societies to persist. And that not doing so will inevitably end our current ways of life. Individually and collectively, we have only two options, to be part of the solution, or to be part of the problem. Each of us individually, and in the various social configurations in which we participate, we need to ask ourselves: “Am I (are we) doing what it takes?” The answers will of course vary with the times, the people involved, the circumstances and much more, and it would be vain to ask that question in a general sense in a paper such as this. There is only one general answer: “We need to do more than we think is enough!” Are we asking the right questions? Instead, I would like to ask: “Are we asking the right questions?” Collectively, we seem to select things from our current lifestyle that we’d like to keep, others where we think we might do without, or yet others where we expect to find the substitute technologies that allow us to maintain our comforts while mitigating their impact. But the predominant tendency has been to focus on those things that we don’t want for our future: resource scarcity, lower comfort levels, destruction of ecosystem services or increases in pollution and waste. On the other hand, there is relatively little positive reflection or discussion on “What kind of future do we want?” that starts from first principles and/or is detached enough from the past or the present to draw a ‘Gestalt’ of that future. At first sight, this seems at least in part due to the fact that such a discussion about the future would call into question a number of fundamental assumptions in our societies about right and wrong, about the ideals and ideas underpinning our societies, our values and our institutions. And it is indeed remarkable that there is relatively little attention paid in the (western) sustainability debate to such issues as the galloping world population, the growing inequity between the rich and the poor and between the (politically) powerful and the powerless, the impact of democratic institutions on decision-making, our fundamental values such as individual liberty, the centrality of the capitalist economy, etc. Another evident reason is the fact that such a discussion should involve huge numbers of people if it actually is to constitute an acceptable basis for developing ideas about the future of society. In the past, it was effectively impossible to achieve that, so that fundamental changes in outlook, social organization, values and institutions were developed by small groups, and then took a long time, and often several ‘crises’, to percolate through society and realign it according to these new ideas. In such instances, a relatively small elite led the way, and most of the (relatively small) communities involved followed nolens-volens. Presently, the state of our society and environment do not permit us to take several centuries to sort the current problems out, or to go through a slow process of re-alignment of society on new values and ways of doing things. Though current information technology may actually bring the logistics of this within our grasp, global as well as regional cultural, social, institutional, economic and educational differences, and the fact that globalization implies that growing numbers of people are involved, seem to me to preclude this as a ‘rapid’ way of transforming society unless a widely acknowledged ‘crisis’ or other form of external forcing occurs.3, 4 Be that as it may, I would in this paper like to draw attention to another issue that in my mind complicates any attempt to focus on the fundamental question “What kind of future do we want?” That issue is the nature of the way most of us think. 3 This does, of course, not mean that we should not be designing the kinds of ICT tools that would help facilitate wider communication and discussion about such themes 4 One might legitimately ask, in that context, whether the exponential growth of the interactive and interdependent world community does not preclude fundamental change of the kind needed. Although in many ways that seems the case, as an archaeologist who observed societal processes over many millennia, including the transition of highly sophisticated cultures and societies into different modes of life, causes me to vacillate between pessimism and optimism in this respect – many times humanity seems to have found and implemented novel solutions to emerging problems in the nick of time. Why aren’t we thinking constructively about our future? Any society is in effect an ‘Information Society’ even though the term has only been introduced recently, as dedicated technology developed to process information, based on the scientific and technical concept of information. At the most fundamental level, any society is held together by the way people generate, communicate and interpret information, which is anchored in the language, the categories, the customs and the ideas the society fosters. Through time, each society develops a ‘world view’, a way of looking at, and doing, things that is particular to that society. I will here call that way of seeing and doing things the society’s ‘intellectual tradition’. Such a tradition is in essence path-dependent, i.e. the history of that tradition determines, at any time, its current state, and thereby the options the society has for dealing with its challenges. To understand that path-dependency, we need to acknowledge the fact that our ideas (theories, etc.) are under-determined by our observations. This is most easily understood by referring to the example Atlan gives (1992): Take five traffic lights, each with three states (red, orange, green). The ‘system’ of these traffic lights can assume 35 (= 243) states. But the number of possible configurations of the connections between these states that could explain them is much higher, 325, which amounts to about a thousand billion. That is also the number of random observations we would need to have in order to decide between these configurations, but evidently we never have anywhere near that number of observations.5 Hence, we must assume that our theories and ideas are indeed under-determined by our observations, and (an important corollary) over-determined by pre-existing ideas, patterns of thinking that we apply to each new data-set and that shape our interpretation of it. That over-determination is the principal factor that causes intellectual traditions to be path-dependent, and difficult to change, especially after they have existed sufficiently long to have been applied in many different domains, so that changing them would demand a very large restructuring effort, and therefore a long period of uncertainty in societies’ ways of dealing with things. That then brings me to the first question I would like to discuss in this section: “Does our intellectual tradition, and in particular our scientific tradition, have anything to do with our difficulties in thinking about the future?” I will argue that that is indeed the case – that our reductionist scientific tradition, together with the institutional framework (universities, career structures, etc.) that underpins it (and which is only slowly being replaced), has handicapped us in thinking freely about the future. At the most evident level, the argument runs – in a nutshell – more or less like this. Science, ever since the fourteenth century, has emphasized the need to solidify as much as possible the relationship between observations and interpretations. Thus, these interpretations linked the phenomena investigated to what was already in existence at the time these phenomena were observed, rather than to what was still to come (and therefore could not be observed). This kind of (Natural) History seems to have been the predominant explanatory paradigm, at least until the 18th century (cf. Girard 1990). It necessarily emphasized the explanation of extant phenomena in terms of chains of cause-and-effect and (much later) an emphasis on feedback loops, in both cases linking the progress of processes through time to their antecedent trajectory. Our perception of the past is very different in nature from our perception of the future. Whereas we see and conceive the past by reducing the number of dimensions we observe in the 5 The number of sequential observations would be considerably smaller, as one could extrapolate from them towards ‘trends’, but it would still have to be much larger than is in effect practicable with traditional scientific means. present into a more or less coherent narrative in terms of causalities and certainties, we conceive of the future by amplification of the number of dimensions experienced in the present, describing it in terms of alternatives, possibilities and probabilities. The long-standing emphasis in science on linking present to past has therefore resulted in a kind of science that is essentially reductionist, achieving a sense of ‘reality’ or ‘truth’ by simplification. In particular, it has emphasized thinking about “origins” rather than “emergence”, about “feedback” rather than “feed-forward”, about “learning from the past” rather than “anticipating the future”. The inevitable corollary of that tendency is the fragmentation of our world-view that we now see as one of the main handicaps in our attempts to understand the full complexity of the processes going on around us. It has been institutionalized in the way academia is structured. This kind of reductionist science has in the last twenty-five years come under increasing attack from the ‘Complex Systems’ perspective emerging in the 1980’s on both sides of the Atlantic. It assumes that in order to get a realistic representation of reality, we need to study emergence, feed-forward and develop a generative perspective to which the amplification of the number of cognized dimensions is essential. This seems to indicate that the current predicament is more due to over-investment in the long-standing reductionist approach than anything more fundamental, and that, at least in theory, it should be possible to transcend our relative incapacity to focus on the future. Of course this would be a huge undertaking, requiring us to develop fundamentally different ways of schooling our young ones from the very beginning, as well as completely changing the way we practice science, the nature of our academic institutions, etc. But if, in principle, it is conceivable, then we may want to consider whether doing so would help us attain sustainability for our societies by developing a desirable perspective on the future and adopting a road map to attain it. However, if I now put on my archaeologists’ glasses and include the many millennia of human evolution in my argument, rather than focusing on the (more or less 2500-year old) western intellectual tradition, this long-term perspective adds questions of two kinds, concerned with (1) human communication and (2) human cognition. Let us look at the communication argument first. “What is the impact of the human means of communication on the way we think about the past and the future?” One of the salient characteristics of the long-term evolution of the human species is the fact that people have, over time, aggregated into larger and larger groups, and created, time and time again, the institutional and organizational frameworks that enabled them to do so. From the point of view that we have chosen here, i.e. that joint information processing is what keeps a group of people functioning together as a society, this process of aggregation seems due to the following cybernetic loop (van der Leeuw 2007): Problem-solving structures knowledge —> more knowledge increases the information processing capacity ––> that in turn allows the cognition of new problems ––> creates new knowledge —> knowledge creation involves more and more people in processing information ––> that increases the size of the group involved and its degree of aggregation –> creates more problems ––> increases the need for problem-solving ––> problem-solving structures more knowledge … etc. This loop has driven people from living in small groups roaming across the countryside and living off gathering, hunting and fishing, to the present, highly complex, societies that involve billions of people. But what are the consequences for human communication? Initially, as such small groups lived together most of the time, they had the opportunity and time for multi-channel communication – spoken language, gestures, body language, eye context and any other kind of communication. This allowed for the long-term accumulation of trust and understanding that allows for the reduction and correction of a wide range of communication errors. As the groups grew, the increase in information processing involved drove people to reduce the time spent in meeting each other. On the one hand, this was facilitated by the fact that new subsistence techniques enabled the (now somewhat larger) interactive groups to settle down in villages where they would run into each other daily, thus cutting down on the time involved in seeking each other out. On the other, as fewer channels of communication were used in the shorter interactions involved, spoken language won out as the main means of communication between people seeing each other infrequently and for short periods of time. Ultimately, as networks of communication grew even larger, to the point that they exceeded spatially aggregated groups and/or the temporal limits of individual contacts, writing was invented. The written message could transcend the here and now both spatially and temporally, and it had the further advantage that writing down the information enabled one to suppress all undesirable (emotional) aspects of the communication, further reducing the probability of misunderstandings or errors. This need for communication to become more precise, in order to avoid misunderstandings and errors, must also have had an impact on language itself, requiring the communities concerned to develop more and more precise ways of expressing themselves in an ever shorter time. That impact, it seems to me, must have been visible in a proliferation of more and more, and ever ‘narrower’ concepts (categories) at any particular level of abstraction thus reducing the number of dimensions in which these concepts could be interpreted. Simultaneously, an increase in the number of levels of abstraction itself compensated for this fragmentation, so that one could still find ways to ‘lump’ over these increasingly narrow concepts along crosscutting dimensions. My conclusion is therefore that the reductionist way of thinking in science is also part of a wider and more enduring tendency to focus more and more on language as a means of (sequential) communication in which each concept dealt with fewer and fewer dimensions of the phenomena described. And this, of course, puts the whole question of the reversibility of that tendency to fragmentation and reductionism in a different light. Next, let us ask a third question: “What may be the role of human cognition in focusing our thinking more on an “a posteriori” or “ex-post” perspective as opposed to an “a priori” or “ex ante” point of view?” The last twenty years, research in ethology, palaeoanthropology and palaeotechnology is making it ever clearer that over the two million years of so of the existence of (proto-) humans, the cognitive capacity of our species has evolved considerably. In particular, we can now cogently argue that in that period, the capacity of the human short-term working memory (STWM) has grown from 2 +/- 1 dimensions to 7 +/- 2 dimensions. In concrete terms, this means that modern humans (Homo sapiens sapiens) can effectively juggle up to seven or eight sources of information (or dimensions of a problem). In combination with the advances in communication just outlined, that increase in STWM has enabled our species to develop the hugely complex material and conceptual world in which we live. But the important point here is not what this has allowed our species to do, but rather what it cannot do because of this fundamental limitation in its STWM – as human beings we cannot grasp in our minds problems of which the complexity exceeds seven or eight dimensions. What are the consequences of that constraint on the human representation of the (very complex) world around them? This depends on whether human beings are looking at the past or at the future. When they consider the past, and specifically when they wish to ‘explain’ processes of which they know the outcome (i.e. how did things in the past lead up to the present?), the very large number of potentially relevant dimensions (representing the complexity of the phenomena and processes in their fullest extent) is reduced by selecting from among those dimensions a limited number that can be dealt with mentally, and then creating a narrative that makes a plausible case for what led up to the specific outcome experienced. But when considering the future, so that there is no single outcome that can serve as a focus for such a narrative, the best that can be done is to create multiple narratives (scenarios), each invoking different dimensions, none of which will entirely ‘explain’ what will happen. Probabilities can then be assigned to them as a measure of the extent to which they seem ‘realistic’. This fundamental limitation to the number of dimensions that the human mind can handle, then, explains at yet another level our bias towards relating the present to the past, and raises the question whether the human mind itself will ever be able to deal with the almost infinite number of dimensions involved to design a future and the roadmap needed to achieve it. It converges with Atlan’s argument presented earlier in the paper, that our ideas are necessarily underdetermined by our observations and over-determined by past ideas that have ‘worked’ or seemed to, but are not necessarily applicable to the current situation. Why is constructing a different perspective on the future so important? But human cognition is only one side of the (asymmetric) interaction between people and their environment, the one in which the perception of the multidimensional external world is reduced to a very limited number of dimensions. The other side of that interaction is human action on the environment, and the relationship between cognition and action is exactly what makes the gap between our needs and our capabilities so dramatic. The crucial term here is ‘unforeseen’ or ‘unanticipated consequences’. It refers to the wellknown and oft-observed fact that, no matter how careful one is in designing human interventions in the environment, something is highly likely to go ‘wrong’. It seems to me that this phenomenon is due to the fact that every human action upon the environment modifies the latter in many more ways that its human actors perceive, simply because the dimensionality of the environment is much higher than can be captured by the human mind. In practice, this may be seen to play out in every instance where humans have interacted in a particular way with their environment for a long time – in each such instance, ultimately the environment becomes so degraded from the perspective of the people involved that they either move to another place or change the way they are interacting with the environment. Or to put this in more abstract terms, due to human interaction with the environment, the ‘risk spectrum’ of the socio-environmental system is transformed into one in which unknown, long-term (centennial or millennial) risks accumulate to the detriment of shorter-term risks. What happens? Imagine a group of people moving into a new environment, about which they possess little knowledge. After a relatively short time, they will observe ‘challenges’ that this environment poses, and they will ‘do something’ about them. Their action upon these challenges is based on an impoverished perception of them, which mainly consists of observations concerning the short-term dynamics involved. Yet these same actions transform the environment in ways that affect not only the short-term, but also the long-term dynamics involved in unknown ways. Over time, little by little all the frequent challenges become known and are modified by the society’s interaction with the environment, while the unknown longer-term challenges that are introduced accumulate. Ultimately, this necessarily leads to ‘time-bombs’ or ‘crises’ in which so many unknowns emerge that the society risks being overwhelmed by the number of challenges that emerge simultaneously. It will initially deal with this by innovating faster and faster, as our society has done for the last two centuries or so, but this ultimately is a battle that the society can only lose. Whether it wants to or not, there will come a time that it drastically needs to change the way it interacts with the environment, so that the whole cycle begins anew. Why has the need for a different perspective remained hidden for so long? Following a range of experiments, the behavioral psychologists Kahnemann and Tverski and their associates (Tverski 1977; Tverski and Gati 1978; Kahnemann and Tverski 1982) have concluded that similarity and dissimilarity should not be taken as absolutes. On the basis of their conclusions, one can argue for the following model of categorization (cf. Figure 2) Once an initial comparison between unknown phenomena has led to the tentative establishment of one or more categories, these categories are tested against other phenomena to establish which phenomena might be subsumed in them. In such testing, the category is the subject and the phenomena are the referents. There is therefore a bias in favor of similarity. But when the relevant categories are firmly established, the process is inverted: the categories become the referents and the phenomena the subjects, so that the comparisons are biased Figure 2: The categorization cycle. For explanatowards dissimilarity, and it is determined tion, see text. which phenomena, after all, did not belong in the categories established. Recalling the fact that societies in effect define their environment, it is thus relevant to ask how the above dynamic of categorization applies to that process. The important point here is that we are dealing with the definition of a relationship between two phenomena, society and environment, which can therefore be viewed from the perspective of either (cf. Table 1). • • • • • • Society (subject) is compared to nature (referent) The cohesion of nature, its unknown aspects, its strangeness and force are amplified; The confusion and the handicaps of society are accentuated; nature is viewed as uncontrollable and dangerous; Society is passive in a natural environment that is active and aggressive; Change is attributed to nature, and people have no other choice but to adapt to nature; Natural changes tend to be viewed as dangerous, because they are beyond the control of people. • • • • • • Nature (subject) is compared to society (referent) The cohesion and strength of nature is diminished; its known aspects seem to be more important; The strength and cohesion of society are emphasized; nature loses its dangerous appearance; Society is viewed as active and dangerous, and the environment as passive; Society is the source of all change, creating (or destroying) the (passive) environment; Society-induced changes are as beneficial as they are under control of people. Table 1: Two perceptions of the relationship between society and its natural environment, depending on which of the two is taken as referent. Society can be seen as the referent and what surrounds it as the subject of the comparison, or the environment is the referent and society is the subject. Although, in everyday usage, we do not make a clear distinction between these two cases, looking at them very closely reveals an interesting paradox. Notably, it emerges that in the interaction between these complementary perspectives, the dangerous aspects of the natural dynamics are systematically exaggerated, and the dangerous aspects of the societal dynamics undervalued. This encourages society to increasingly intervene in its natural environment by giving the impression that society’s actions can reduce the risks it runs, whereas in reality, society reduces by its actions the predictability of natural phenomena. The more society transforms its surroundings, the less it understands them. But the cognitive feedback loop behind this drive nevertheless induces society to intervene more and more … generating more and more consequences, while at the same time hiding them. Hence the ubiquitous phenomenon of ‘unanticipated consequences’, and our societies’ impression that we can indeed ‘control’ the natural environment as long as we keep intervening in it more and more drastically. Can we get better at thinking about the future? Although it initially seems as if our intellectual and scientific tradition, the size of our interactive population, the nature of many of our languages, the under-determination of our theories by our observations and the limitations of our human short-term working memory are as many challenges to our capacity to fundamentally change the nature of our thinking by explicitly focusing on the future, there are many examples of individuals or (small) groups of people who have nevertheless done so with some degree of success, from classical Greek philosophers via Leonardo da Vinci to 18th and 19th century science-fiction authors (such as Jules Verne or Paul Deleutre6). They have been able to design utopias or to extrapolate positively from their lifetime observations into the future, even though some of these ideas were only realized years or centuries later. Inventors have also been able to anticipate, and most of us call on our “intuition” when we need to do so. This raises the question whether these limits to our capacity to think about the future might be overcome? And if so, what is needed to do so? In essence, at the level of the discussion in this paper (and thus disregarding for the moment the many political and other issues that would also have to be dealt with), these two questions are fundamental in my mind to the oft-cited need ‘to change our culture drastically’ if we want to create sustainable societies in sustainable environmental contexts. As the first of these questions can be debated but not answered without answering the second, I intend to devote the next sections of this paper in particular to that latter question. Overcoming the limitations of human STWM Although I am not an expert in the field at all, it seems to me that the ICT revolution has indeed created the conditions for us to overcome the fundamental limitations to our brain’s calculating capacities that are imposed by our short-term working memory. Present-day computers do 6 Writing under the pseudonym Paul d’Ivoi, this French author anticipated the idea of modern telecommunications (wireless and television) have the capacity to deal with an almost unlimited number of dimensions and information sources in real time, and thus to overcome what appeared at first sight to be the most fundamental of the barriers mentioned above. But that capacity has not fully been exploited because of our long-standing and ubiquitous scientific and intellectual tradition, which has emphasized the use of such equipment as part of the process of dimension-reduction that provides acceptable explanations, rather than as a tool to increase the number of dimensions taken into account in our understanding of complex phenomena. Under the impact of complex systems science this is clearly changing (as seen, for example, in the increased use of high-dimensional Agent Based Models), but much more needs to be done, mainly in developing conceptual and mathematical tools as well as appropriate software. Overcoming the under-determination of our theories by observations Similarly, and with the same caveat that I am not a professional in this field, I am under the impression that the very recent revolution in IT capacity to continuously monitor processes online, and to treat and store the exponentially increased data streams that are generated by such monitoring, points to the fact that we may indeed be on the brink of (at least partly) overcoming the under-determination of our theories by our observations. The reduction in the size and cost of the monitoring equipment is quickly bringing such massive data collection within reach. Simultaneously, the development of novel data-mining techniques is helping us to make sense of the data thus collected, or at least in selecting the appropriate data to be scrutinized in order to better inform our theories. Transforming our scientific and intellectual tradition Although I am not among those who fall easily for panaceas, I do believe that the complex (adaptive) systems approach is a useful first step on the way to fundamentally transform our scientific and intellectual tradition from studying stasis and following choosing simple over complex explanations, to studying dynamics, with an emphasis on emergence and inversion of Occam’s razor (increasing the number of dimensions taken into account). Clearly, we have a long way to go in this domain, but the rapid and substantive advances in certain fields, including physics, biology and economics, coupled with the rapid recent spread of this approach in Universities in many parts of the world and the growing awareness of the need for more holistic approaches in such domains as sustainability and health, cause me to be moderately optimistic about our chances of transforming our scientific and intellectual tradition. Transforming education All three domains above do, of course, need major investment and development, and this will not come easy or be rapid. But, maybe it is because I am an educator as well as a researcher, by far the greatest challenge from the perspective of human and financial capital and effort appears to me to be in the domain of education, from the earliest childhood throughout university and into adult life. The current education system in the developed world is, overall, no longer adapted to the challenges of the 21st century, among which those to do with sustainability loom large. Essentially, we have to move away from knowledge acquisition aimed at question-driven research towards challenge-focused education that aims to help deal with substantive challenges, from ‘linear explanation’ in terms of cause-and-effect to ‘multi-dimensional projection’ in terms of alternatives, from one-to-many teaching (in which an instructor tells students what to do, what is right and what is wrong), to many-to-many teaching in which instructors and students all interact, learn and teach. At the same time, we must develop education systems that stimulate the acquisition of creativity, risk-taking and diversity rather than conformity and risk-adverseness. In doing so we must harness the tools referred to above, but more than anything we must ‘bend’ minds around to thinking in new, uncharted, ways. In doing so, we are handicapped by the fact that economics, career structures, evaluations, disciplinary momentum and many other factors and dynamics are stacked against success in this area. I am currently involved in one effort to move in this direction, at the university level, in an institution (Arizona State University) that has experimentally embraced a different academic philosophy and is trying to implement that organizationally. Describing this would largely exceed the scope of this paper and the space allotted to it, but I would be willing to share some of these experiences with the group if that were of interest. The communication challenge The underlying communication challenge is how to communicate other than linearly and in writing or speech with an increasingly large number of partners at very variable distances. This is the challenge that was in my mind responsible for the particular development referred to above: narrower and narrower concepts, and the consequent fragmentation of our perspective on the world. Contrary to some, I do not think language is subject to deliberate change – it adapts itself to human needs and ideas in a ‘bottom-up’ process. But even if it were possible to transform the ways in which we speak and write, we would still have an essentially linear communication tool. *** References Atlan, H., 1992, Self-organizing networks: weak, strong and intentional. The role of their underdetermination. La Nuova Critica, N.S., 19-20 (1/2): 51-70. Evernden , N., 1992, The Social Creation of Nature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press Kahnemann, D.P., Slovic, P. & Tversky, A. 1982, Judgment under uncertainty: heuristics and biases, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Luhman, N., 1985, Ecological Communication, London: Polity Press McGlade, J., 1995, Archaeology and the ecodynamics of human modified landscapes. Antiquity 69 (262): 113-132 Tversky, A., 1977, Features of similarity, Psychological Review 84: 327-52 Tverski, A., & Gati, I., 1978, Structures of similarity. In: Cognition and Categorization (E. Rosch & B.B. Lloyd, eds.), pp. 79-98. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum van der Leeuw, S.E., 1998, “ La nature serait-elle d'origine culturelle ? Histoire, archéologie, sciences naturelles et environnement ”, in Nature et Culture (F. Joulian & A. Ducros, eds.), pp. 8398 Paris: Errance. van der Leeuw, S.E., 2007, Information processing and its role in the rise of the European world system. In: Sustainability or collapse? (eds. R. Costanza, L. J. Graumlich & W. Steffen), pp. 213–241. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press (Dahlem Workshop Reports).