U.S. Supreme Court Case Preview Did I

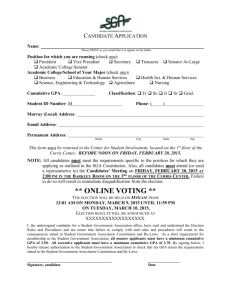

advertisement